The PEN World series showcases the important work of the more than 140 centers that form PEN International. Each PEN center sets its own priorities, but they are united by their commitment to advocate for imperiled writers, promote literature from all cultures and in all languages, and advance the right of every individual to speak freely.

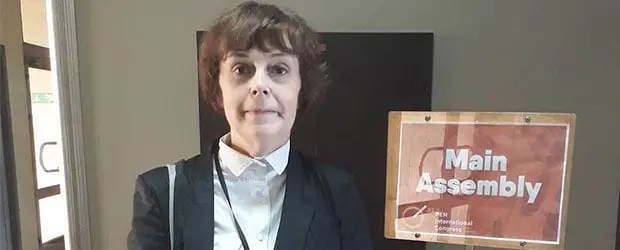

In this series, PEN America interviews the leaders of different PEN centers from the global network to offer a window into the literary accomplishments and free expression challenges of their respective countries. This month, we spoke with Elisabeth Eide, vice president of Norwegian PEN.

What is a project that you have been working on in recent months?

In the last few years, PEN Norway has piloted a new kind of organizational structure, whereby we have developed subcommittees. These subcommittees are mainly headed by non-board members, though a board member is on each committee to serve as a link between the board and the committee. We have subcommittees on whistleblowers, on diversity, on publicity issues (mainly press) and, of course, on writers in prison. The subcommittees follow up on these issues, remain very aware of what is going on in the field, and arrange relevant events. For example the subcommittee on [whistleblowing] had an event about health workers and whistleblowing. We also had a highly successful event on police and whistleblowers. This structure has increased PEN’s visibility because these events have attracted wide audiences and, in turn, more members.

I’m on the diversity board. Recently, we had a meeting with a group of people who are opposed to the honor and shame culture. Through the diversity committee, we try to create a space for new voices.

Not too long ago, our secretary general and our president went to Moscow to award the Ossietzky Prize [PEN Norway’s prize for outstanding efforts for freedom of expression] to Edward Snowden, because he could not come to Norway. We lobbied for Snowden to come to Norway, and attempted judicial procedure, albeit unsuccessfully. He’s stuck in Russia.

What are the key free expression challenges facing your region, and what kind of work have you been doing to overcome them?

PEN Norway has a commitment to working to overcome challenges to freedom internationally. Recently, delegations from Norway visited China. We wrote a letter to the Norwegian Minister of Culture expressing that she should address the freedom of expression issues, in particular regarding the fate of Liu Xiaobo. Unfortunately, we did not see her do that, likely because there is so much at stake when it comes to Norwegian export interests.

We also work with PEN Afghanistan, our sister organization, and PEN Turkey. In Turkey, for the past several years we’ve sent people to observe the court cases against writers and journalists there. We have developed close friendships with some of those persecuted people, whether in prison or out of prison. PEN Norway tries to make space for Turkish writers. We’ve had events with Turkish exiles. Traditionally, Norwegian PEN has worked with Turkey, but this work has been bolstered by the Vice President of International PEN Eugene Schoulgin, who lived in Turkey for six years.

On the international scale, we engage in a variety of ways and domestically, we also try to put pressure on our government when necessary.

Would you share with us a sense of the literary traditions in your region?

Before I did my Ph.D., I studied literature. In a sense, I am a woman of literature, though I do read very much international literature. I would say there is a tendency to write in an autobiographical manner. This is an old tradition, from a stream of bohemian literature in the 1890s. Proponents would say, “You should write your own life, and you should write about your own scandals, your own sufferings.”

Today, some people criticize this style for being introverted or unethical. There have been huge debates both about Karl Ove Knausgaard, who’s now world famous for My Struggle, and Vigdis Hjorth, who is equally famous for her last book which is partly on incest.

I haven’t read Knausgaard I have to admit, but I have read Hjorth and she’s a fabulous writer, but there’s been this kind of ethical critique on the fact that when they lay bare their own lives, they also lay bare the lives of others.

Another trend is toward the working class novel. It is certainly an implicit, if not an explicit, critique of very much of the literary world being somewhat middle class.

. . . and update us on something new in the literary world of your region today?

There are many people who have a migrant or refugee background gaining popularity—not in large numbers, but they are there. There is a great writer in Indonesia, Eka Kurniawan, who is a Member of Indonesian PEN. I have published some books at the same publishing house as him.

Who is a writer from your region that we might not know about? Would you introduce us?

Swedish PEN President Elisabeth Åsbrink. I read about her literature, but I haven’t had a chance to read her books yet!