PEN Haiti: Growing with a New Generation

The PEN World series showcases the important work of the more than 140 centers that form PEN International. Each PEN center sets its own priorities, but they are united by their commitment to advocate for imperiled writers, promote literature from all cultures and in all languages, and advance the right of every individual to speak freely.

In this series, PEN America interviews the leaders of different PEN centers from the global network to offer a window into the literary accomplishments and free expression challenges of their respective countries.

What is a project that you have been working on in recent months?

PEN Haiti is a young branch of the PEN network. Although the center opened only a few years ago in Port-au-Prince, it has rapidly expanded to other regions within Haiti. In just about five years, PEN Haiti has opened nothing less than three other regional centers across the country, in the towns of Gonaïves, St. Marc, and Petit Goave. During this period, the center has focused on bringing literature on and raising awareness of free expression issues throughout the whole country. As we build our inner networks, the management of the different centers needs to be organized. So, a center manager has been brought on board to create a synergy between the different regional centers and help them structure their key action fields.

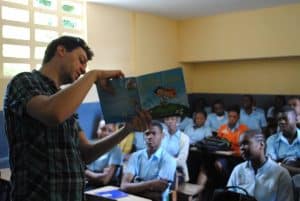

In recent months, we have been planning a project titled “Empowering Haitians with Expression” (EHE), which focuses on two key aspects: providing spaces for ordinary Haitians to engage in dialogue with literary and artistic figures based in Haiti and from the Haitian diaspora, and taking forums for dialogue and creative debate out to the provinces, where PEN Haiti has a burgeoning network of centers in small towns such as Gonaïves. Through a five-day festival held in July and the establishment of regular programming following this event, PEN Haiti plans to provide spaces where ordinary Haitians can engage with literature and the arts and also become comfortable with adding their voices to the discussion. By exposing a broader swath of Haitians to the arts and encouraging them to use creative expression to add their voices to debates about key economic, political, and social issues affecting them, we aim to strengthen Haiti’s democracy from the ground up and ensure that recent gains are passed on to the next generation.

What are the key free expression challenges facing your region?

Haiti, with its history of dictatorship and oppression, has slowly but surely found its way back to a sociopolitical environment where free expression can be exercised. Despite improvements in the situation for free expression over the past 20 years, exercising this right remains challenging, is most often abused, and can easily become a cacophony—another way to drown free and righteous expression. Fortunately, many associations now defend vividly this principle of free speech in an objective and thoughtful context, among them PEN Haiti, by giving a context that is at the same time attractive and challenging while focusing on important themes and results.

PEN Haiti is keen to ensure that constitutional free expression guarantees are upheld and that the boom of Haitian literature in recent years continues and is shared with the next generation. At the same time, we want to open avenues of expression to those who may not be writers or artists, but would like to add their voices to key debates. Including voices from the broad Haitian diaspora, which has produced a number of noted writers and artists, is another priority.

Forums for the exchange of views in Haiti’s stratified, segmented society remain rare, and PEN Haiti wants to fill this gap by providing this type of regular space for interaction. In recent months, we have noticed at our nascent regional centers that there is a huge enthusiasm and appetite for such programming; for example, PEN Gonaïves has held three well-attended literary events in the past three months. The EHE project will build on this success to ensure that local communities have avenues for access to the creative arts and for the development of their own expression.

Would you share with us a sense of the literary traditions in your region?

Haiti’s rich literary tradition includes a form of storytelling known as “Tire Kont.” It is delivered through metaphors and proverbs and steeped in our rich, colorful Creole language. The Tire Kont is usually a non-conventional gathering where the lead storyteller opens the session shouting “Krik!” to which the audience is enjoined to answer “Krak!” Only then can the Kont begin.

Kont sessions often include short stories that impart life lessons and, over the course of the evening, involve audience members, asking them to share their own proverbs to which other members must guess the correct answer.

…and update us on something new in the literary world of your region today?

There is a new generation of women writers on the literary scene in Haiti.

Back in the early 1990s, with the fall of the dictatorship, the new freedom of speech, and the more active and assertive presence of the feminist movement, a solid feminine literature emerged and has found its place in the Haitian general literary scene that was mostly occupied by men during the twentieth century and whose choices of themes were mostly political and indigenous. These women are not only poets and novelists, they are also playwrights and stand-up comedians. It is the first time in the Haitian literary story that a few women are working as full-time writers and building a significant body of literary work. They have opened literary pages to other venues of life such as intimacy in relationships, the family, women’s condition, the dialogue with their own bodies, etc. These women are Yanick Lahens, Évelyne Trouillot, Kettly Mars, Emmelie Prophète, Paula Clermont-Péan, Kermonde Lovely Fifi, and Gaëlle Bien-Aimé, to name a few.

Back in the early 1990s, with the fall of the dictatorship, the new freedom of speech, and the more active and assertive presence of the feminist movement, a solid feminine literature emerged and has found its place in the Haitian general literary scene that was mostly occupied by men during the twentieth century and whose choices of themes were mostly political and indigenous. These women are not only poets and novelists, they are also playwrights and stand-up comedians. It is the first time in the Haitian literary story that a few women are working as full-time writers and building a significant body of literary work. They have opened literary pages to other venues of life such as intimacy in relationships, the family, women’s condition, the dialogue with their own bodies, etc. These women are Yanick Lahens, Évelyne Trouillot, Kettly Mars, Emmelie Prophète, Paula Clermont-Péan, Kermonde Lovely Fifi, and Gaëlle Bien-Aimé, to name a few.

Stand-up comedy, most likely due to the influence of North America, has become trendy in Haiti. It can also be viewed as a mutation of the Kont tradition, although its purpose is not to moralize but to entertain using satirical depictions of the biases and flaws of the society in general.

Who is a writer from your region that we might not know about? Would you introduce us?

There is nowadays a new generation of young poets that write mostly in Creole. Creole is taking more and more room as the expression tool of the whole community. It is everywhere: on the radios, the newspapers, in schools’ curricula, and in literature. A few years ago, the first Haitian Creole Academy was established. This is a social movement that places Creole, spoken by the majority of Haitians of lower socioeconomic conditions, in a kind of confrontation with French, the language inherited from the colonial power and spoken by the elite minority. French is seen by a vast majority of Haitians as the language of exclusion. But the struggle will last long because, paradoxically, speaking French is also seen as social climbing and an accomplishment by many.

So, we would say these new poets, some of them very fine ones, who are using Creole as a weapon to be heard and to pass on their claims and frustrations, are worth noticing. Their names are James Noel, Inema Jeudy, Bonel Auguste, Makenzy Orcel, Coutechève Aupont, Mehdi Chalmers, and many others.