School districts like Walton are letting bigoted, unfounded claims dictate access to literature for all

Last week, reports circulated that Walton County School District in Florida decided to remove a slate of 58 books from its library shelves. In the days since, the Walton County Superintendent, A. Russel Hughes, has clarified that the district received an external group’s list of 58 books that it had “deemed inappropriate,” and that in response, Hughes decided unilaterally to pull from circulation any of the listed books that were in the District’s school libraries. In total, 105 physical copies of 24 different titles were removed (a full list is appended below).

The ban in Walton County fits a pattern that PEN America has observed across the country over the past year, as documented in our recent report, Banned in the USA. School district leaders are caving to demands to remove books–whether from outside groups unaffiliated with the schools, by parents, or by politicians–and in so doing are failing to exercise due diligence, follow their policies, or work to safeguard students’ First Amendment rights.

But what happened in Walton County also illuminates the outsize influence fringe groups can have in public education when they meet little resistance.

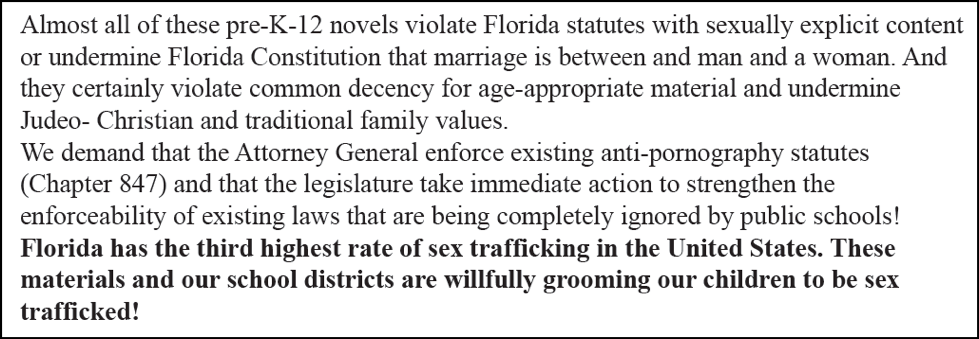

An examination of the list underlying this ban makes this fact abundantly clear. The list was allegedly emailed to districts across Florida by the nonprofit, the Florida Citizens Alliance, and comes from their “2021 Objectionable Materials Report: Pornography and Age-Inappropriate Material in Florida Public Schools” (provocatively named the “Porn in Schools Report” on their website). The report alleges that specific books “contain indecent and offensive material” and that “almost all” of the works included “violate Florida statues with sexually explicit content” and “undermine” the Florida Constitution. Ominous as such claims may sound, the report is in fact largely an anti-LGBTQ+ screed that contains little objective support for its assertions. That this report has effectively now reduced students’ access to literature in Walton County–as well as in other Florida school districts–is deeply alarming.

Before we delve further into the content of this report, we must first detail what has happened in Walton County and why it qualifies as a case of book banning.

“I haven’t read one paragraph of the books at this time”

Superintendent Hughes claimed in a press release on April 22 that “no book ban has occurred in Walton County.” But his actions fall well within the parameters of what constitutes a book ban. Superintendent Hughes made a unilateral decision to decree a set of books off-limits in response to a public challenge, removing these books completely from student access for an indefinite period of time. Hughes has even stated that he may decide to remove more books as he sees fit.

As discussed in PEN America’s recent report, there are long-standing best practice guidelines that school districts across the country adhere to in order to safeguard students’ First Amendment rights; these best practices are designed to ensure that books are not removed from school libraries by school or district administrators in an ad hoc manner. Yet that is exactly what happened in Walton County. This is all the more concerning because the District does in fact have a policy on “Challenged Materials,” which states clearly that challengers must present their concerns in writing on a printed form, and that these concerns must then be evaluated and decided upon by a committee of teachers, education media specialists, parents, and students that reads and discusses the material.

There is no evidence that Superintendent Hughes followed his own district’s policy when deciding to ban these books. In fact, at the time of the banning, Superintendent Hughes stated, “I haven’t read one paragraph of the books at this time.”

This is a shocking abrogation of the responsibility of a school district leader to uphold students’ rights to access ideas and information. It means that the decision to ban the books was taken not only without any formal process or adherence to district policy, but was also based entirely on the fact that these books were listed in an external, unexamined report. In other words, Superintendent Hughes has effectively delegated the authority to determine access to these books for Walton County students to this outside group rather than to anyone involved in education in the district itself.

The danger of this decision is particularly evident when one considers how these 58 books came to be included in this report, as well as the ideology of the group that compiled it.

What is this list and where did it come from?

The Florida Citizen Alliance (FLCA) is a 501(c)3 nonprofit focused on K-12 education reform in Florida schools. The organization claims that, “Florida children are being indoctrinated in a public-school system that undermines their individual rights and destroys our nation’s founding principles and family values.” The FLCA first developed its “Porn in Schools Report” in 2017, looking at just nine books that it alleged contained pornography. They then expanded this list to include 44 titles in 2019, and 58 titles in 2021. The 15-page 2021 report includes the list of 58 books with links to reviews compiled by FLCA’s volunteers, a brief discussion of how the works allegedly violate Florida statutes, and some excerpts and illustrations from 10 specific books whose content touches on sexual activity, sexual assault, and LGBTQ+ identities.

Why 58 books? And why these 58 books? Based on the 2019 report, it seems that these titles are a combination of books the FLCA has learned of from their supporters, as well as a list of LGBTQ+ books compiled by the hyper-partisan website Christian Patriot Daily. The 2021 report states that their list of “indecent” books in schools is “by no means exhaustive,” but there is no clear criteria for why any of these books were included in the first place.

The lack of criteria and variegated sourcing helps to explain the seemingly random assemblage of books on the list, which includes works that have been challenged in other districts for years like Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, alongside books that have seemingly not been challenged before like The Purim Superhero (by Elisabeth Kushner and illustrated by Mike Byrne) or Everywhere Babies (by Susan Meyers and illustrated by Marla Frazee). The ragtag nature of the report is also evidenced in the fact that it is full of typos, errors, and misspellings. Mommy, Mama, and Me by Lesléa Newman and illustrated by Carol Thompson, for example, is listed as “Mammy, Mama and Me.” Noted author Judy Blume is listed as “Judy Blu.”

How are these books evaluated?

The crux of the FLCA’s report is the claim that the availability of the 58 books in schools violates Florida laws because of alleged sexually explicit content, characterized as “indecent,” “inappropriate,” “pornographic,” and “obscene.” These allegations do not appear to adhere to legal definitions nor take into account relevant federal jurisprudence, resulting in a lack of foundational integrity of the report.

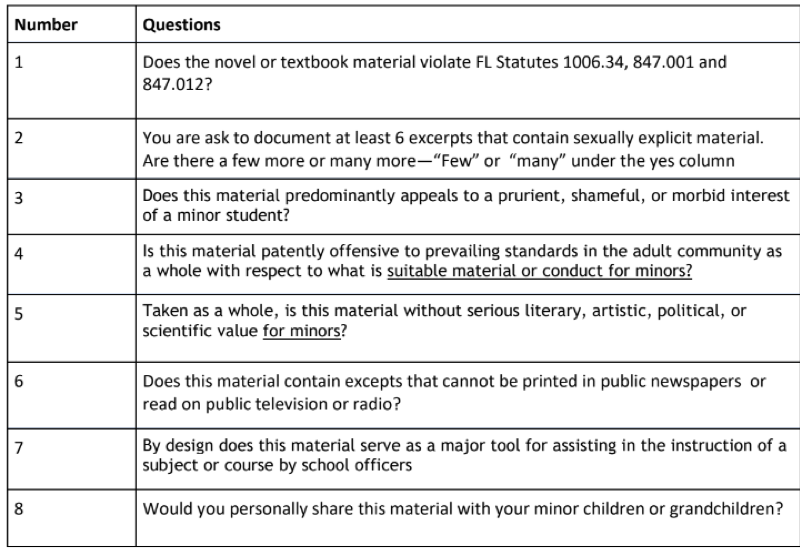

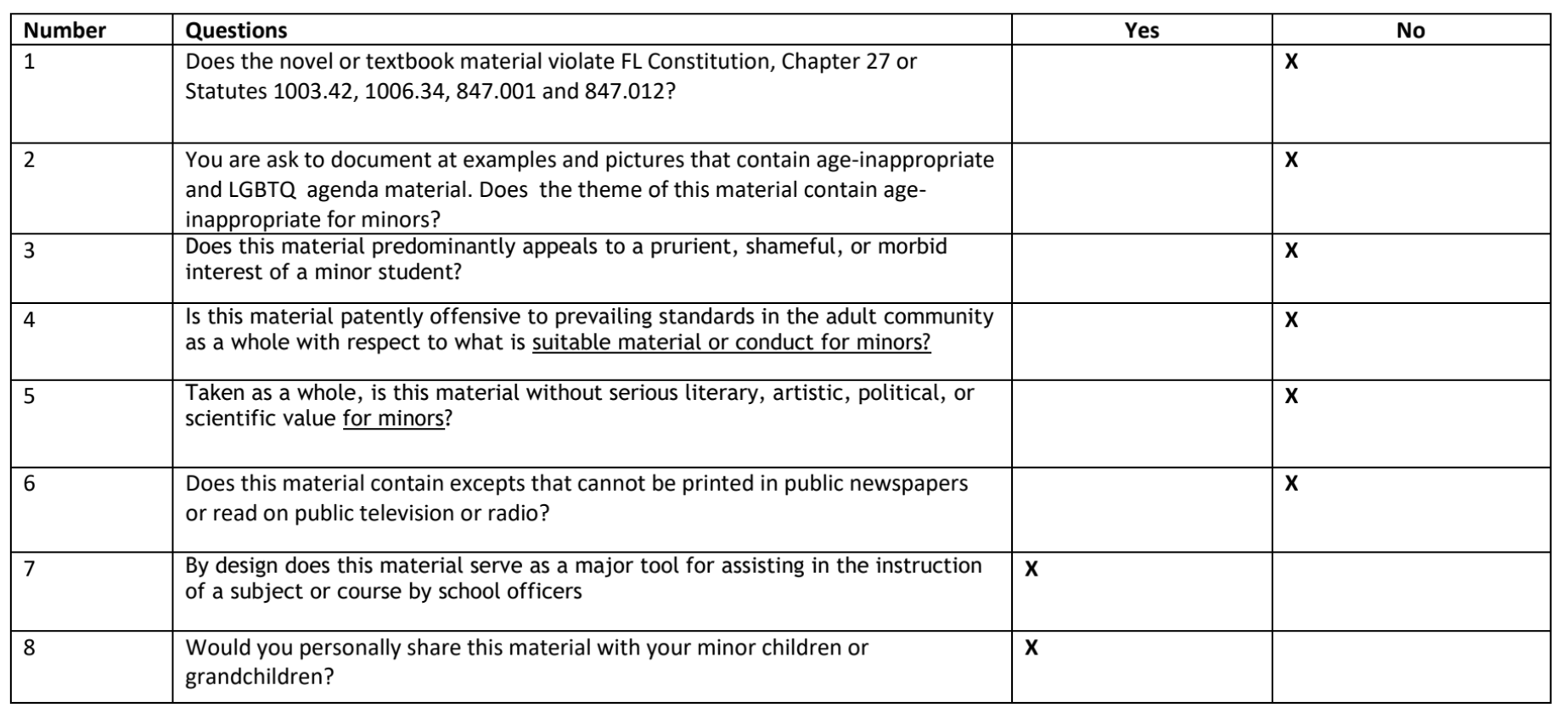

Despite the FLCA’s charge that the books listed violate Florida law, there is no indication that the volunteer-only reviewers, identified only by last name and county, have the particular experience or knowledge required to support such an allegation. There is, for example, no indication that any of these reviewers were educators or librarians, that they had particular knowledge of Florida law or jurisprudence related to obscenity, or that they were even parents of school-aged children. Nonetheless, these volunteers were assigned specific books to read and directed to fill-in review templates for them, where they assessed the content and value of the books on a range of questions, such as whether they violate specific Florida statutes, whether they are “obscene” by meeting aspects of the U.S. Supreme Court’s long-standing test for obscenity (known as the Miller test), and whether they are “appropriate” for schools and minors. Further, many of these questions are subjective or involve judgments that require professional expertise–like whether a book could be a “major tool for assisting in the instruction of a subject or course” and whether it could be “printed in public newspapers or read on public television or radio.”

Given legal experts’ conclusions that the books that have become controversial for their alleged sexual content in the past year would not meet the legal definition of obscenity, it seems highly doubtful that these reviews should be treated as authoritative.

Citizens and advocacy groups are of course free to conduct volunteer exercises such as those of the FLCA and to collect these opinions, and they should have the opportunity to share their concerns with school boards as part of a considered process. When these opinions are deemed definitive and used as a pretext for reducing the availability of books in public school libraries, however, it becomes a matter of serious public concern. These evaluation templates are hardly unbiased or constructed to foster objective responses. Rather, they are designed to bring about an intended outcome–to find exactly what they want to find. They use legal-sounding language to evoke fear and worry about the availability of these books in schools–yet are not supported by relevant expertise or authority.

Particularly illustrative is question 8 of the FLCA review form, which asks: “Would you personally share this material with your minor children or grandchildren?” This question reinforces the idea that a single person’s preference is determinative when examining the availability of books in public schools, when in fact schools are meant to serve diverse, pluralistic communities who might have wildly different responses to such a question. This reflects the deeper concern with the whole report: that it presents itself as objective and thorough, when in fact the process used to generate its conclusions is in direct contravention to the principles that should guide a public school library and its duty to uphold students’ rights to access a wide range of information and ideas. Moreover, legal precedent in this area has established that the First Amendment bars prescriptions of orthodoxy. Thus, the opinions of one set of parents in a school or district cannot be used to deny or otherwise undermine the rights of all students.

There is little sound basis to the assertions in the report–apart from anti-LGBTQ+ animus

By design, the report’s roster of books includes a preponderance of titles with LGBTQ+ characters, and the review process itself is slanted toward finding that these books contain “illicit” content. Though there are cases where books on the list do include sexual content, it is also the case that many of them do not; they merely contain LGBTQ+ characters. The conflation of the two–arguing that LGBTQ+ content, even when it has no explicit reference to sexual conduct, is by its very nature “pornographic” or “obscene”– reflects a long-held animus toward gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer stories and art, and calls back to a time, before the 1960s, when such content was routinely censored by government authorities. As with the “Don’t Say Gay” bill passed in Florida this legislative session, the FLCA appears interested in resurrecting this dark past, undoing the gains in visibility and normalization made by the LGBTQ+ community that are now reflected in children’s literature.

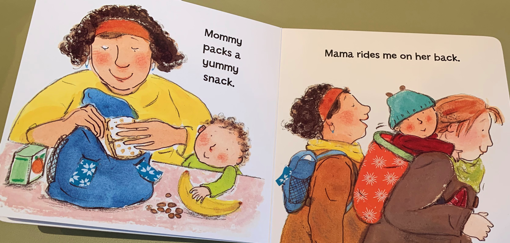

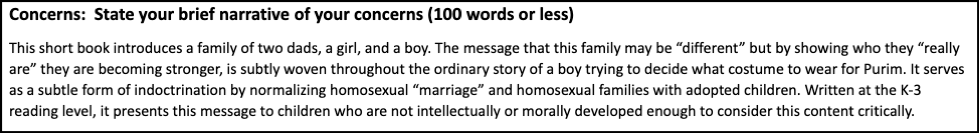

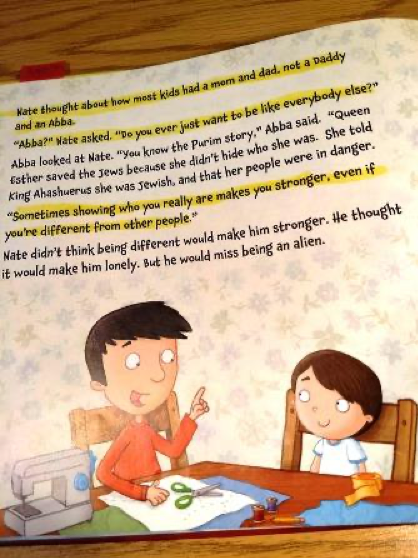

For example, the review of The Purim Superhero linked in the report finds evidence of “bias and indoctrination,” and that the book “is subjecting all readers to LGBTQ agenda.” Yet the examples offered by the reviewer only include dialogue and pictures of two dads with their children. While the reviewer does acknowledge that the book does not appeal to a “prurient, shameful, or morbid interest of a minor,” they make it clear that they found the family in the story unacceptable and dangerous for younger readers. They responded to the review template affirming that the book is “patently offensive to prevailing standards in the adult community as a whole with respect to what is suitable material or conduct for minors.” As shown in an excerpt from the review below, the entire basis for this assertion rests on the opinion of the reviewer that “normalizing homosexual ‘marriage’ and homosexual families with adopted children” is “a subtle form of indoctrination.” This is an argument rooted in anti-LGBTQ+ hate; it should not be taken as a serious basis on which to restrict access to a book in a pluralistic democracy committed to free expression and individual liberty.

This anti-LGBTQ+ orientation holds across many of the books included in the report and the assertions made about them, which in many cases involve similarly strained arguments. In another example, the reviewer for Melissa by Alex Gino (formerly published as George), selected the following passage as an example of how the book contains “explicit and detailed verbal descriptions or narrative accounts of sexual excitement, or sexual conduct and that is harmful to minors.” The passage reads: “The bodies looked the same to George. They were all girls’ bodies. If George were there, she would fit right in. They would ask her name.” This passage is clearly an exploration of identity; it has little to do with sexual conduct or excitement whatsoever.

While there are other examples in the report of images and text that deals with sexual assault, or, comprehensive sexual education (e.g. about puberty), there is a consistent framing of these texts as inappropriate or obscene just by virtue of their touching on sexual conduct at all. This is hardly sufficient justification for banning these books or deeming them illegal to make available to students; in fact, most public schools incorporate lessons on sexual education, sexual assault, and sexually transmitted diseases, as part of a duty to inform rising adults on matters of consent and public health. Nonetheless, the FLCA seems to view any availability of such information– just as they view any representation of LGBTQ+ lives–as inappropriate or indecent, regardless of students’ rights, or of the desires of other Florida parents who might want their children to have the opportunity to learn about these issues in schools.

A final claim in the report is that many of these books including The Purim Superhero are violating the Florida Constitution, specifically Section 27 (adopted in 2008), which reads: “Inasmuch as marriage is the legal union of only one man and one woman as husband and wife, no other legal union that is treated as marriage or the substantial equivalent thereof shall be valid or recognized.” While it is true that this same sex marriage ban remains on the books in Florida, it is abrogated by the 2015 Obergefell v Hodges Supreme Court decision legalizing same sex marriage in the United States.

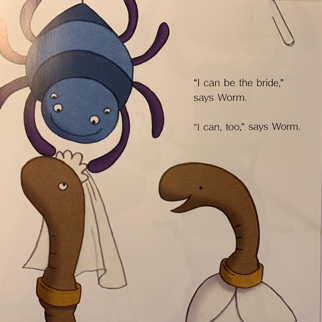

Including this language from the Florida Constitution gives the false impression that FLCA has a legal basis for the censorship of LGBTQ+ representation efforts. The influence of this mistaken understanding is obvious in the review for the children’s picture book Worm Loves Worm by J. J. Austrian, which states, “this book undermines the concept of marriage between a man and a woman. It is age-inappropriate for use in public schools using public tax dollars.” This language matches that of the Florida Constitution and reinforces the idea that government support– “public tax dollars,”–should only be spent on materials that support its definition of marriage, advancing FLCA’s goal to portray LGBTQ+ topics as inherently wrong or illegal.

Evoking the Florida Constitution in this way appears to be a rhetorical move by the FLCA to advance their political and ideological attack on LGBTQ+ people through children’s books. Even more concerning is that this flawed argument is influencing actual school district decisions.

Some books were actually not deemed pornographic or inappropriate for schools

Given the way in which the “Porn in Schools Report” was used to justify banning books in Walton County, a final observation about it is most surprising. This is the fact that 8 titles included in the list of 58 have reports where the reviewer did not deem the book inappropriate for schools or children. Of these eight, six titles were classified as devoid of “flawed or objectionable” material, while in the other two cases, the reviewer simply declined to answer any of the organization’s questions. Regardless of these verdicts, and without justification, all eight titles remained listed in the FLCA’s report, and were banned in Walton County–seemingly without anyone reading these reviews.

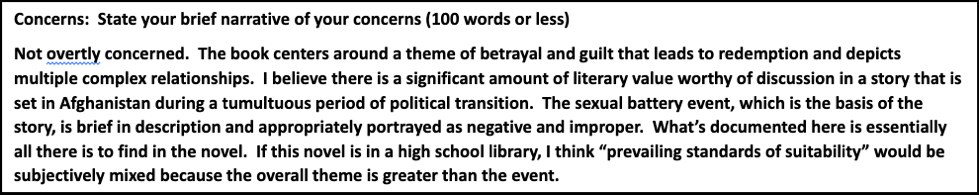

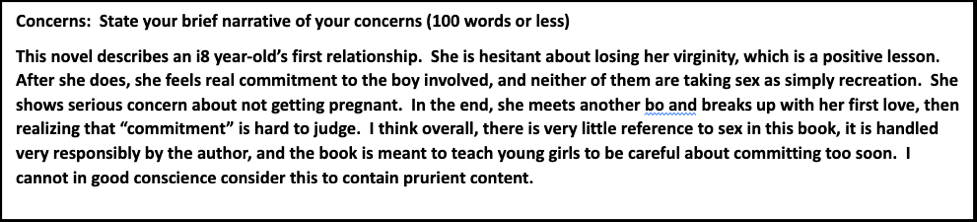

For example, reviews for some of the titles actually affirm that they have literary and artistic merit, and that they do not have content that their specific reviewers indicated was inappropriate. This includes titles that were pulled in Walton County: The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini and Forever…, by Judy Blume. Relatedly, while the reviewer for The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas indicated that they found “the repetitiveness of curse words and/or grossly inappropriate words for young ears” offensive in the book, they also indicated that the book could serve as a “major tool for assisting in the instruction of a subject” and that they would personally share the book with a minor. Regardless, it was pulled from shelves in Walton County too.

In another example, the book Everywhere Babies appears on the “Porn in Schools Report” list, and in the wake of news of it being banned in Walton County, it has been profiled in some news outlets. Surprisingly, the review linked in the report did not find that the book has any objectionable content. As with The Hate U Give, the reviewer actually indicated that the material could be used for instruction in schools, and that they would share the book with a minor. That these and other books were swept up in Superintendent Hughes’s book ban helps demonstrate what is so flawed about the current wave of book banning– due diligence, policy, and process are being all-too-frequently abandoned by school authorities.

In the Cross Hairs of Perilous Circumstance

This analysis covers only a fraction of the material within the FLCA’s “Porn in Schools Report,” its relationship to book bans across Florida, and the broader “Ed Scare” that is seeing educational gag orders pass statehouses, teachers fired, and librarians threatened. While Walton County provides the clearest example of the pernicious influence of this Porn in Schools Report, there are other districts like Polk County where it has also been used to justify suspending access to books for students, and there are other groups circulating other lists of targeted books to districts in other states.

Groups like FLCA are growing in number and power, undertaking book reviews that mirror the professional work of librarians and educators in order to attain a veneer of legitimacy. And they are having some success– pressuring school districts to buckle to their political and cultural agenda. The school administrators that ignore best practices and forgo their policies in the face of these groups’ demands are depriving students of materials they have a right to receive. In so doing, these administrators are telegraphing to LGBTQ+ students or those with other marginalized identities that their constitutional rights as learners–and in fact their very identities–come secondary to fears of political backlash.

Indeed, Superintendent Hughes in Walton County stated as much when justifying his decision to pull the books immediately, noting that it was done “especially in the context of Florida’s recent legislative session”–which PEN America understands to be a clear reference to the recent passage of Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law and other bills pertaining to school library materials. Hughes stressed his desire to protect his community: “With reports of movements underway across the state coupled with legal implications and the potential undue stress to my District and staff, I am not willing to place any WCSD staff in the cross hairs of this kind of perilous circumstance.”

It is unclear what jeopardy the Superintendent envisioned for WCSD staff. While the claims in FLCA’s “Porn in Schools Report” are certainly presented with shock value, even a cursory review should make clear that the Report is a conglomerate of hateful stereotypes, bias, and animus against LGBTQ+ people, coupled with radical, fringe ideologies about schools “grooming” children that have been associated with QAnon conspiracy theorists. While the Report does have examples of sexual education and other sexual content in books, there is no indication that school libraries maintain materials that would rise to the level of pornography, nor it is by any means a given that all or most parents would object to this material being accessible by their children in schools. Overall, the Report is unquestionably more concerned with criminalizing LGBTQ+ lives and stories and banning them from public schools, than with objectively evaluating the educational value of particular books to students.

That such a convoluted, biased, and vague report is being used as the basis for serious, consequential decisions by school districts is a dire signal of how worrisome the spread of school book banning has become–and the perilous tightrope that schools, educators, and librarians are having to walk as a result of this censorship.

The 24 Books Pulled from Walton County Library Shelves:

- This One Summer by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki

- Forever… by Judy Blume

- Dreaming in Cuban by Cristina García

- Outlander by Diana Gabaldon

- The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy

- Melissa (previously published as George) by Alex Gino

- Real Live Boyfriends by E. Lockhart

- Tricks by Ellen Hopkins

- The Truth About Alice by Jennifer Mathieu

- Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close by Jonathan Safran Foer

- Dead Until Dark by Charlaine Harris

- Unravel Me by Tahereh Mafi

- Sloppy Firsts by Megan McCafferty

- Drama by Raina Telgemeier

- A Court of Mist and Fury by Sarah J. Maas

- The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

- Beloved by Toni Morrison

- The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas

- Killing Mr. Griffin by Lois Duncan

- Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher

- Nineteen Minutes by Jodi Picoult

- The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie

- The Kite Runner: Graphic Novel by Khaled Hosseini

- Almost Perfect by Brian Katcher

This update for PEN America was written and compiled by Jonathan Friedman, Nadine Farid Johnson, Dr. Tasslyn Magnusson, and Sabrina Baeta.

All exhibits included in this update come from publicly available documents and were excerpted as they appear in the FLCA’s 2021 “Porn in Schools Report” or the review forms linked from it.