Derrick Barnes Calls Canceling School Visits Cowardly

The superintendent of the Alabama schools that canceled called Barnes ‘a controversial guy’

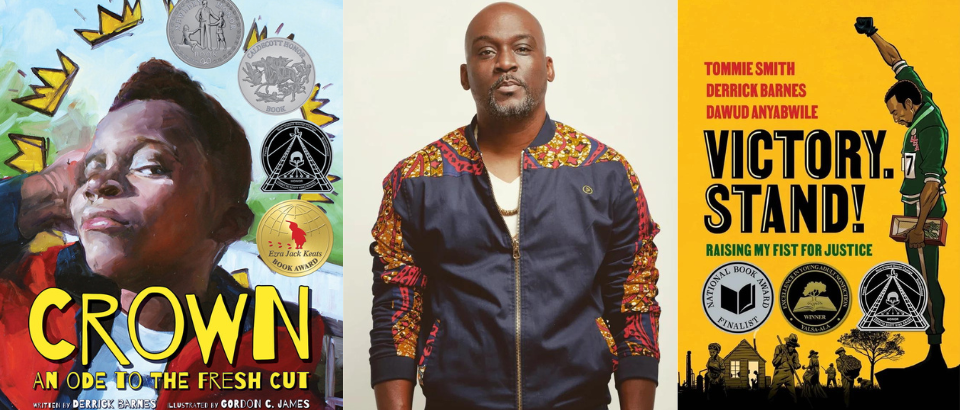

Photo: EyeSun Photography

By Lisa Tolin

Derrick Barnes was supposed to speak to several schools in Alabama during Black History Month.

The award-winning author would talk about falling in love with reading. He’d talk about his struggling years, “which were seemingly, you know, forever.” He’d talk about resilience, and faith, and hard work.

“I pretty much have the same presentation no matter what the book is, because I know these babies are going to face the same thing no matter what age they are,” he says. “And a lot of my message is just not giving up on yourself and to keep pushing through.”

But kids in the Birmingham suburbs won’t hear that message, because Barnes’ visits were mysteriously canceled. Hoover City School officials originally claimed they lacked proper documentation for a contract. Superintendent Dee Fowler later said a parent had complained, and Fowler called Barnes a “controversial guy.”

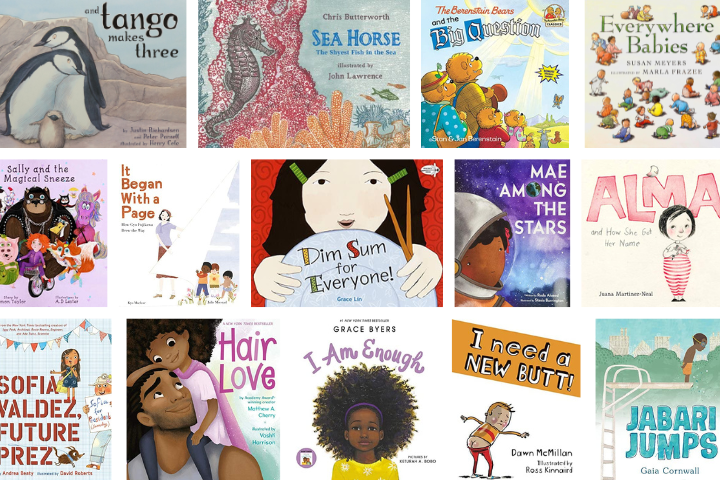

Barnes isn’t sure how he’s controversial, though of course “it might just be this whole CRT crap.” Most of his books center Black joy. His latest, the National Book Award finalist Victory. Stand!: Raising My Fist for Justice is written with Tommie Smith to tell his story of social activism.

“I don’t know what it was. You know, maybe they don’t want their children reading about Black resistance or Black love or Black joy. I don’t know,” he said, calling the decision “very cowardly.”

Some teachers in the community signed a letter protesting the cancellation of Barnes’ visit, and parents bombarded the superintendent’s office with phone calls. Some even set up a gofundme to pay Barnes for the nearly $10,000 in lost income.

In conversation with PEN America, Barnes said he was grateful for the support, and wanted to encourage writers to “keep telling the truth” and not back down.

“It is unfortunate that we have to deal with this right now, but in order for us to get over this hump, we need more parents to be more vocal and more active. And on my end, we have to continue to write the Blackest books that we can write – the most Latino and Asian and Muslim and gayest books that we can – just keep telling your truth. We can’t allow them to stop us doing God’s work,” he said “I can’t wait to piss off the next Southern superintendent somewhere, because I can’t be stopped.”

Have you ever had a school visit canceled before?

You know, I’ve been doing school presentations since 2005. That was the first time I did one, when my first two books came out. I remember my eldest boy, who’s 22 now, was in pre-K. I remember seeing him walk into the library. I didn’t even get paid, but they had a nice fruit basket spread out for me. It was very nice. I remember that. So I have been doing it since 2005. Never had anybody cancel.

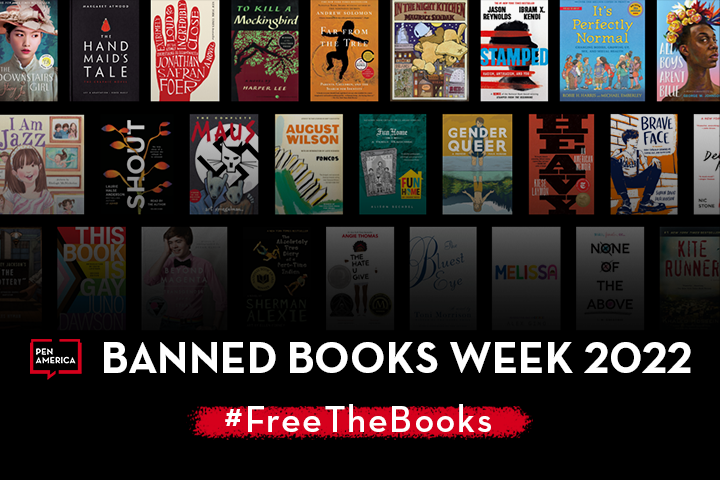

We know it’s happening to other authors, and obviously the climate has changed. PEN America found that some of your books were banned last year in Central York, Pennsylvania. In those years since 2005, have you noticed a difference in how schools are reacting?

The sort of crazy thing is, you know, we had our first black president elected 2001 to 2008, two very successful terms. And I remember having a conversation with my brother that this is not going to end well, because that’s how America rolls with these ebbs and flows. You know, I had no idea that we would end up where we ended up in 2016. But I kind of felt like there would be some backlash for having this brilliant, gentlemanly, good father, good husband, Harvard graduate as president for eight years. And sure enough, we elected a reality TV star and a failed businessman. And I think that’s what changes the temperature in this country. We went to the polar opposite of what we thought was progress. And he just kind of turned that up on his head.

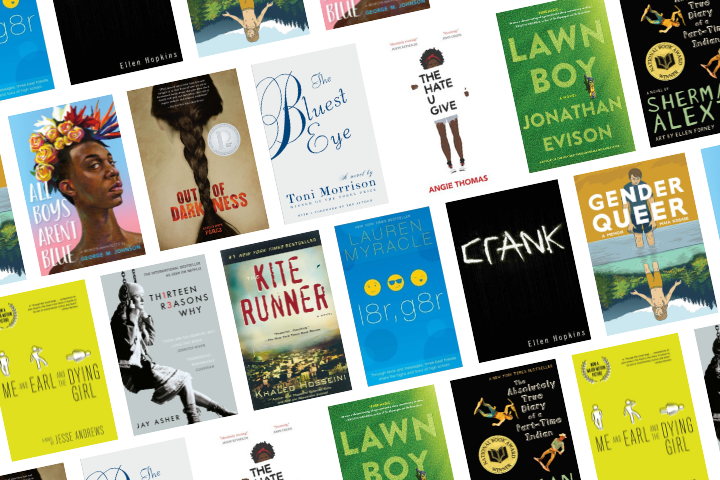

“If you have Black children in your district and you turn away a Black children’s book author, that really says a lot about how much you care about those children. So that’s unfortunate.”

And then 2020, when George Floyd was lynched on camera, well, I’ve never been contacted by so many celebrities and talk show hosts, radio hosts. Black books were just flying out of the bookstores. The very next year, I think it was an election year, so there were new governors and new congresspeople. And they started these big bans at the end of 2020, 2021. So it’s always these ebbs and flows when we think we’re making progress. All these Confederate statues started coming down and all those things started to change, and an NFL football team changed its name. And all these Black books were getting a lot of attention. And most of them were Black books about anti-racism or books about African-American history and the history of racism. And I guess the backlash was now just to ban these books.

I think a lot of it is that they just don’t want white children to learn the truth about American racism, because if they do, I think that will mess with the social order of things. I think we’re all just being played and really it has nothing to do with race or gender. It’s all about economics and this social structure. I just so happened to get caught up in its nonsense.

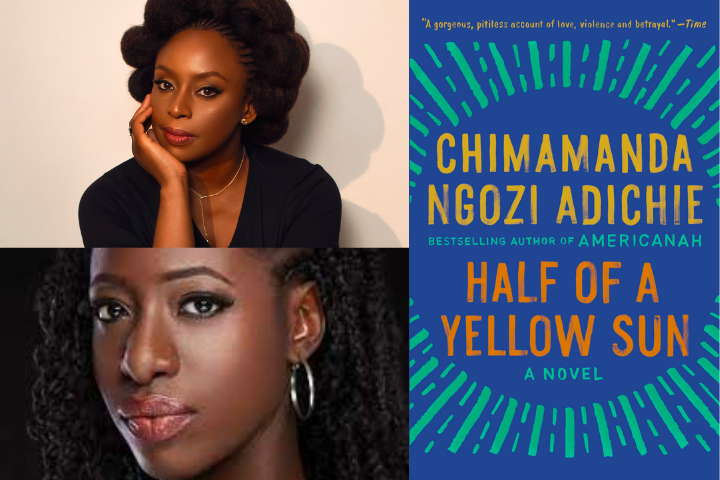

You have said you feel a particular responsibility as a Black children’s book author. What have readers told you about what your books mean to them?

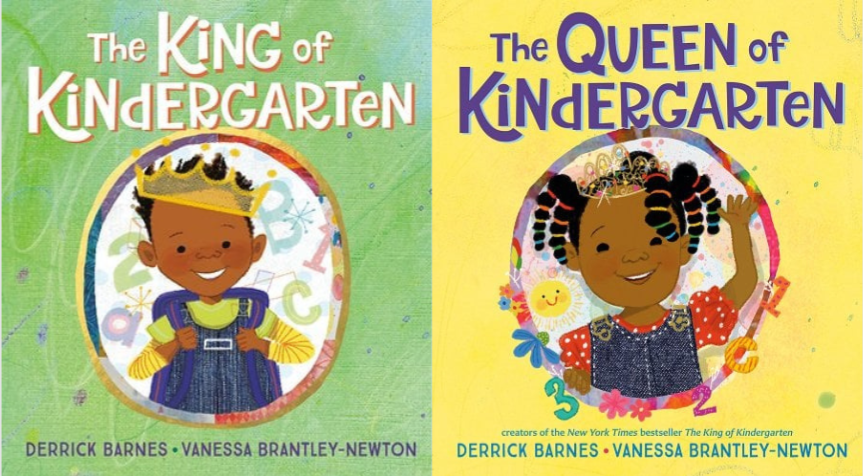

I get pictures every single day. I get a lot of pictures from parents, teachers, especially with my King of Kindergarten and Queen of Kindergarten books and these little beautiful Black children. I try to create my books that way where no matter what racial or what socioeconomic background you come from, you’ll be able to see yourself in these characters. So, you know, it makes my day sometimes when I get a letter from a teacher that has a picture of all of her students wearing little crowns on their heads, and I know I’m doing my job well. I always say I hope I’m doing God’s will.

What does it say to the children whose identities are represented in these books when they cancel an author visit or ban a book?

I think it makes them feel like their humanity is in question. I had a letter from a couple of parents, a few Black parents, saying that their children were really looking forward to me coming and just being able to talk about my experiences of being a children’s book author. And now it’s not going to happen. I used to say I write solely for Black children, but I write a lot for white children as well, especially white children who live in homogeneous types of environments, and they never have the opportunity to meet someone like me. So I think it is even more valuable for white children to meet Black professionals and not just people that they see on film or television and rap videos and this whole stereotypical image of what they think a Black person is.

But if you have Black children in your district and you turn away a Black children’s book author, that really says a lot about how much you care about those children. So that’s unfortunate.

Lisa Tolin is the editorial director of PEN America and author of the children’s book How to Be a Rock Star.