2023 Emerging Voices Fellows | The PEN Ten Interview

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s 2023 Emerging Voices Fellows provide insight into their creative processes, how they’ve developed as artists and writers, and what inspires their literary practice. PEN America’s Emerging Voices Fellowship provides a five-month immersive mentorship program for early-career writers from communities that are traditionally underrepresented in the publishing world. The fellowship nurtures creative community, provides professional development training, and demystifies the path to publication—with the ultimate goal of diversifying the publishing and media industries.

Learn more about this year’s fellows >>

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you? Why?

Vera Blossom: One of the first books I felt really enthralled by was A Tale For The Time Being by Ruth Ozeki. I loved that two characters were connected across space and time via writing — a diary. A lot of the motifs and themes are things that I write about now: water, cyclicity, the malleability of time, nature’s capacity for devastation. Also, if we’re being real, I learned how to read by playing Pokemon Red on the Gameboy with all of its awkward translations and fantasy words, so I still have a special place in my heart for it.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

Lindsay Ferguson: Fiction can essentially function as an autopsy of truth in that it allows us to probe and examine it. We can reaffirm, distort, and subvert truth through our characters and how we shape them – the beliefs they hold, the words they speak, the choices they make. Whether or not other characters in the story (or readers) agree or approve becomes irrelevant. The character is navigating life directly in response to their own personal interpretation of what is true, and that alone prompts us to look closer and consider how that truth resonates within us or doesn’t.

I explore this theme often in my own writing. I’m fascinated by the notion of two or more wants, needs, desires, or experiences being true at once. There’s a tension in trying to hold space for multiple realities that are in conflict, which, to me, is akin to coming to grips with the fact that we’re all wonderfully, painfully human – capable of creating chaos just as much as we’re capable of creating goodness. It’s uncomfortable but it’s also an inevitable result of being alive. I find myself meditating on that tension often in my creative work, and in life in general.

“Fiction can essentially function as an autopsy of truth in that it allows us to probe and examine it. We can reaffirm, distort, and subvert truth through our characters and how we shape them – the beliefs they hold, the words they speak, the choices they make.”

3. Why do you think people need stories?

Joy McKinley: It is quintessentially human to create stories. Our minds do this instinctively, without any conscious effort. It happens when we recount our day, when we describe a meal or that weird dream we keep having.

We build value systems and share cultural beliefs by telling stories. Our identities are formed through the stories we tell ourselves about who we are. Nations are built out of stories. Histories are written (and re-written) with stories. Stories are how we make meaning.

Because we each share this strange experience of being the sole consciousness within a body, stories are required in order to relay our experiences to one another. To be seen. To be understood. There is no relating without story. There is no empathy, no community, no belonging. We need stories to connect, so stories are, to me, one of the most profound curiosities of human existence.

4. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

Jassmine Parks: Meeting my birth mother. Initially it was the asking after her, the hushed whispers that befell my family, the unwillingness to share anything. I was eleven when I learned her name. And what magic it inspired to imagine her as I turned “Kim” over and over in my mind and mouth.

At 12, I unearthed her story. She’d been incarcerated, serving her sentence since I was an infant. There is always, I feel, a tug of the heart towards the mother even when wounded. It made me wild with search. Upon finding her I wrote her a letter and she wrote back; my first memory of communication with my mother was not by voice, but by way of the epistle.

A portal opened up between our two worlds. One in which I peered into the carceral system, my mother fodder of the failed war on drugs and the new Jane Crow. The other in which she saw the transient nature of me shuffling between different homes and systems, including juvenile.

We broke open all of ourselves during those years – our grief, our joy, our love, our sass and our desires. It taught me manifestation and the steadfastness of loving someone.

“There is no relating without story. There is no empathy, no community, no belonging. We need stories to connect, so stories are, to me, one of the most profound curiosities of human existence.”

5. What is your relationship to place and story? Are there specific places you keep going back to in your writing?

Arianne Elena Payne: I’ve had the fortune of calling many places home, quilting them into the fabric of the woman and writer I am. My first, forever, and current home is the South Side of Chicago. No matter how far I go, I am called back to Mississippi’s backyard, up south, to its brownstones, great lake, black belt, and the spirit of an artistic city that don’t quit. Chicago’s bus stops filled with smooth cats schooling me on the promises of joy, a prophetic body of water to the east, and sleet-slick winters as noisy as its summers are all characters animating my writing. I am also a daughter of the South, specifically, Mississippi, Texas, North Carolina, and the DM(V). I lived in Mississippi and Texas as a young girl before moving back to Chicago’s suburbs to live the majority of my life, 8-18. My fresh memory captured the material textures of the South—its overgrown and spacious landscape, dirt roads, and swag as fierce as its heat—and it stayed with me. These homes have inspired a deep reverence of the Black South, a need to continually return home to honor my ancestral lands, and a calling to keep it alive in my work.

6. If you could claim any writers from the past as part of your own literary genealogy, who would your ancestors be?

Zen Ren: Can I claim a living genealogy?

I love how the characters in Kazuo Ishiguro’s work carve out their realities with such limited tools, particularly in the dystopian frame of Never Let Me Go. Before, I’d only seen dystopias conclude in revolution. As a first-generation queer person of color, I already experience dystopia in the living world, and admired this rendering of what it’s like to create your own life within injustice. As a speculative writer I claim this work as part of my literary genealogy because it showed me a real life–the one I knew–within a fantastical world.

Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things struck me with how the characters knead repeatedly through memory, transforming it like malleable dough. The content of our memories are regarded as how we understand who we are, yet it’s also a story we tell ourselves. Watching Roy’s characters stumble across those lines—sometimes purposefully manipulating themselves—illuminated for me how memory is the first fiction we learn to construct, imbued with the same power to elevate and destroy. I write fiction as a way of untangling the fiction inside me. I write to understand what I am, by exploring what I’ve done to myself.

7. What do you read (or not read) when you’re writing?

Denise Rhone: I read for a feeling. Sometimes, a book, a sentence, a word, propels me to kick off my bed sheets and sit before the page. When writing, especially when writing is hard, I am voracious for this feeling–this connection to myself at eight. Eyes closed and listening to my teacher read aloud, I was suddenly overcome with the call to craft stories. I read to rebirth that moment as often as possible.

As you can imagine, it’s hard to know what text will ignite that fire. So, while I do seek out new authors and dust jackets (and occasionally craft books) that might do the trick, I often revisit the eclectic works that have already left their mark: Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong, An Ember in the Ashes or All My Rage by Sabaa Tahir, Sky in the Deep by Adrienne Young, Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz, and childhood favorites like Winter of Fire by Sherryl Jordan.

8. What’s something about your writing habits that has changed over time?

Kristen Yoo Shim: I’ve become less rigid with my habits. I used to set ambitious goals (500 words or 2 hours of writing) and beat myself up when I inevitably failed to hit that goal every day.

While I still carve out time in the mornings to write, I forgive myself if things don’t go according to plan. I take rest days. If I am at the page and nothing comes to me, I journal instead or I read writers I love.

I’ve been far more productive and much happier with this more flexible approach. I’ve also developed mini-hacks that motivate me. I track the time I spend writing. I write first drafts in one fell swoop without rereading them. I give new work a week to breathe before beginning the editing process.

All of these tactics help me feel successful. They increase the probability I’ll be excited to come back to the page. Because that is the most important thing, coming back. I try to preserve and grow that joy of returning to the page as much as possible.

“I write fiction as a way of untangling the fiction inside me. I write to understand what I am, by exploring what I’ve done to myself.”

9. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

Layli Shirani: In a catastrophic world, for those of us who are displaced, dispossessed, identity, like debris, is something to be pulled from the rubble of experience, held up, examined, pieced together like a puzzle, the contours of which are unknown. But as a writer, when you unearth a piece, a piece that looks like nothing to a well meaning “other”, your body tells you that it is yours, a remnant of yourself that you jettisoned on this unending journey toward belonging. Only now you realize that what once seemed vestigial – what you thought you need to discard in order to survive – is actually vital. It is you.

10. What is a moment of frustration that you’ve encountered in the writing process, and how did you overcome it?

D’mani Thomas: My writing process is unpredictable at times. Sometimes I get inspiration or work through writer’s block in the shower, which spoiler alert, is a very unfortunate time to finish writing. With no access to a pen, pencil, or paper, I’ve often forgotten many a stanza. One time I started working through a poem while some of my friends were fighting. (Again, a terrible time to find inspiration).

Things that helped this have been developing my memory so that I can remember lines, or concepts, until I reach a piece of paper. I’ve started utilizing my phone’s notes app when I can. And when those things aren’t available, and life requires me to prioritize something else or be present elsewhere, I trust that the poem will come back when it needs to. People and memories matter. Those things are building blocks of poems, so I like to believe that the more attention I pay to them, the more I can call on them later.

11. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

JJ Xiao: Butt in chair. (Or, alternatively, feet under a standing desk.) Hands on keyboard. Words on screen. Once a day, every day. Building habits saves me from relying on willpower.

I like to keep things simple. There’s an important distinction between writing and thinking about writing. While thought isn’t necessarily the opposite of action, humans suck at multitasking. If it’s not contributing to putting words on the page, I try not to think too hard about it.

12. What do fellowships, workshops, and programs such as the Emerging Voices Fellowship mean to emerging writers? How, if at all, do they help with viewing oneself as a writer?

Lucy Zhou: Although I’ve been writing my whole life, I didn’t call myself a writer until recently, and it is because of the generosity and support of programs like the Emerging Voices Fellowship. In Kazim Ali’s open letter to Aimee Nezhukumatathil, he talks about the need for structural transformation within the literary landscape to serve “difference”—race, gender, class, and disability, which have historically marginalized writers in a system that privileges the wealthy and the white. Writing is often viewed as a solitary act, where you’re tinkering with a manuscript at your desk that you’re not sure will ever see the light of day. But writing is also a question of knowledge and access and power, inextricable from the relations of production under capitalism that govern our everyday lives. The Emerging Voices Fellowship creates spaces where emerging writers of color can learn and grow together; for many of us, this is our first writing workshop, our first glimpse into the publishing industry, our first time meeting writers we admire whom we now have the honor of calling mentors. I want to dispel the myth of the lone writer/genius because we are all products of who and what came before us and the communities we’re part of. And that’s the greatest gift I’ve received as an Emerging Voices fellow: being in community with writers who inspire me every day to return to the page.

Sola Mahfouz & Malaina Kapoor | The PEN Ten Interview

In Afghanistan, laughter is as much a part of life as sorrow and pain. People crack jokes while hiding from bombs in basements, finding humor in their grim reality.

Jillian Tamaki & Mariko Tamaki | The PEN Ten Interview

Your first big break up, the first loves of your life, are your friends. Those stories are really interesting, meaty stories.

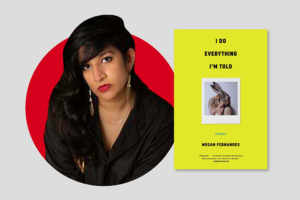

Megan Fernandes | The PEN Ten Interview

My focus was just on the insecurity of being. Everything that happened narratively came from focusing on that feeling as much as possible.

Bronwyn Fischer | The PEN Ten Interview

My focus was just on the insecurity of being. Everything that happened narratively came from focusing on that feeling as much as possible.