Sola Mahfouz & Malaina Kapoor | The PEN Ten Interview

September 12, 2023

In conversation with Rachel Powers, the PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Center Program Coordinator, Sola Mahfouz and Malaina Kapoor discuss the cowriting process, literature’s unique power to document, and the intersections of luck and resilience. (Barnes & Noble, Bookshop)

Sola Mahfouz and Malaina Kapoor’s Defiant Dreams (Ballantine Books, 2023) is the telling account of an Afghan girl who was prevented from attending school under the Taliban and educated herself in secret in order to attend college. Mahfouz, the book’s subject, and Kapoor, a young Indian American human rights activist, cowrite a dynamic, poignant, and frank memoir that gives way to new perspectives on learning.

1. Defiant Dreams is Sola’s story of restriction from schooling under the Taliban, her own self-education, and her work to become a quantum-computing researcher. It’s a story about resilience. To what extent do you see this book as offering a theory of change?

Malaina: Sola’s story is a powerful reminder of the remarkable human ability to overcome. It is indelible proof that education, especially for girls and women, is an incredible catalyst for change. But her story is also predicated on luck and a chance connection to the internet. As much as Defiant Dreams is a story of resilience, it is also a reminder of the unimaginable obstacles that continue to choke so many girls and women in Afghanistan, no matter how hard they struggle for freedom.

Sola: I try to tell my story so that it doesn’t become a plea for pity or a claim for glory. It is a witness to the hardships that Afghan women endure in their pursuit of education. My journey was a series of obstacles, each one more daunting than the last. The world seemed to conspire against me at every turn. Yet, through my story, I try to reject the labels of victim or hero that are often imposed on Afghan women. I hope that through Defiant Dreams, the world can see Afghanistan beyond the headlines, and see Afghans in their hopes, dreams, and everyday struggles in a world that is full of complexity and contradictions.

2. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

Malaina: From the moment Sola and I first met, identity informed our connection. My Indian-American background helped build an unspoken understanding between us based on the overlap between our two cultures. There were broad similarities, like the presence of arranged marriage and the importance of family. But there were also subtle moments—like Sola’s relationship to her mother or her final goodbyes as she left for America—that echoed within my own family. We often remarked that these shared experiences were like another language, so difficult to explain to those who hadn’t lived them. But ultimately, it was this language that allowed me to live Sola’s experiences through her stories and then translate them to the page.

Sola: The stories I tell, the writing I do, the questions I ask—they are all shaped by the atmosphere of my homeland, the framework of its history, culture, and politics. Afghanistan is more than the place where I grew up. My thoughts and ideas are all rooted in Afghanistan. It is like my skin, inseparable from me. Of course, I am learning and expanding my worldview, but the root of my writer’s identity is my Afghaness and every day I feel I am going deeper in that direction.

“I hope that through Defiant Dreams, the world can see Afghanistan beyond the headlines, and see Afghans in their hopes, dreams, and everyday struggles in a world that is full of complexity and contradictions.”

3. Defiant Dreams is a memoir, and it’s also cowritten. How did you, as two authors, approach writing one author’s narrative in first-person? In what ways did writing this book change, expand, or restrict your ideas of the “self?”

Malaina: Sola and I first met in 2020, at the height of the pandemic. We started by just talking over Skype. Sola told me stories from her life and I wrote them down into the chapters that eventually became Defiant Dreams.

It’s impossible for one person to tell another the personal stories from their life in a vacuum. Instead, Sola and I spent hours talking about both of our lives, telling stories about our brothers or childhoods or favorite books. Within weeks, we developed a close friendship. Eventually, we began flying across the country to visit each other for Thanksgiving or summer break. The beauty in this process was that we still maintained our very distinct senses of self. We exist to each other as full people because we are no longer just colleagues, but more like sisters.

Sola: Writing about oneself is a delicate task. It is easy to fall into the trap of either trivializing or exaggerating one’s experiences, or of avoiding the depths that might be hidden beneath the surface. That is why I am grateful for the collaboration with Malaina on this book. She helped me to see my story in a broader context, to structure it with clarity and coherence, and to probe into the nuances and complexities of my emotions. Through the writing process of Defiant Dreams, I learned not only about writing something so personal, but also about myself.

4. Access to education is a central driver of this story. What more did you learn about education within your own value systems through the process of writing this book?

Malaina: I grew up with stories of the incredible sacrifices my parents and grandparents made for education, and so its importance was always something ingrained within me. Writing this book helped me comprehend the significance of education on a global scale, to understand more fully the transformational power of schooling for those in the most dire circumstances. Especially given the recent Taliban takeover in Afghanistan, increased access to education feels more urgent than ever. I’m hopeful that Defiant Dreams is a reminder of this reality.

Sola: I sometimes wonder what I would have become without education. I had a restless curiosity, but without the right objects to direct it towards, it might have been wasted on trivial matters and idle gossip. The world might have never heard my name or my voice. I remember how learning changed me in subtle ways, even in Afghanistan. It altered the way I walked as if it added something to my posture and my presence. It gave me the courage to speak among men when women were expected to be silent and submissive. It allowed me to express my own opinions when women were supposed to defer to the authority of men. It shaped my identity and my confidence and made me feel that what I was saying mattered.

“Writing this book helped me comprehend the significance of education on a global scale, to understand more fully the transformational power of schooling for those in the most dire circumstances.“

5. How have you navigated censorship—and self-censorship—in your own writing?

Sola: Some topics have affected my life profoundly, but they are also contentious and debatable. When I write about them, I base my perspective on the events that have shaped my view. I avoid making broad and generalized statements.

6. In one passage of the book, you write, “We found that the only times of lightness were those we created, and so we developed a dark sense of humor to callous us against reality.” In what ways was humor a part of your writing process? How did comedy allow you to connect to each other as coauthors, and give you ways to articulate what is sometimes brute and violent content?

Malaina: Parts of this book were incredibly difficult to write because they showcased the absolute darkest sides of humanity. For months at a time I felt like I was living two realities, one buried in stories of civil war and air strikes and brutal attacks, and another amongst the everyday world. But we tried to infuse lightness into this book, as well, to show that the story of Afghanistan is not just a story of violence. That’s where the laughter and joy came from—from stories of a grandmother tricking her husband into educating their daughters, of girls trapped at home sneaking out for ice cream, of a plane tipping into the sky towards America.

Sola: In Afghanistan, laughter is as much a part of life as sorrow and pain. The darkest moments often inspire the most hilarious jokes. People crack jokes while hiding from bombs in basements, finding humor in their grim reality.

7. What do you see as the role of writers in society?

Malaina: Writers can harness the power of storytelling to shine a light on issues that might otherwise pass us by. That was our goal with Defiant Dreams—to use the personal to communicate the political. In many ways Defiant Dreams is unique to Sola’s life experiences, but it is also the story now of a generation of girls and women in Afghanistan who have been denied basic human rights and are fighting to be free. We hope the book inspires action from those who have the power to make a difference.

Sola: Good writers reveal the value of society. They show where the problems are. They allow us to connect beyond space and time.

8. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression in Afghanistan today?

Malaina: The Taliban is by far the biggest threat to free expression and freedom more broadly in Afghanistan. Afghan women and girls are most affected by the group’s draconian policies, which have gradually and systematically stripped half the country of their basic human rights over the last two years. Women are now banned from workplaces, secondary schools, and most other public spaces. Within the last few weeks the Taliban has further restricted girls’ access to education and banned women from beauty salons, one of the last places they could gather or earn an income. Today, there are Afghan mothers who have experienced more freedoms than their daughters likely ever will. This is a human rights catastrophe that we cannot afford to turn away from.

“In Afghanistan, laughter is as much a part of life as sorrow and pain. The darkest moments often inspire the most hilarious jokes. People crack jokes while hiding from bombs in basements, finding humor in their grim reality.“

9. There are facets of this book that feel archival—that both document human rights abuses, but also give documentation to resistance. How do you see literature as serving our collective memory?

Malaina: The stories of wars and atrocities cannot be told only through statistics. Literature has the unique power to transport readers to places and circumstances that are not their own, to communicate the emotions that comprise different dimensions of human existence. It enriches our collective memory by allowing us to feel what others have felt before.

Sola: The stories of the past are buried if they are not told. For example, now I want to learn more about life under the communist regime in Afghanistan. I want to feel the texture and rhythm of life at that time. But I find it hard to read anything that goes beyond the narratives of wars and coups, the violence and the politics. I feel that life in that time is lost, erased from memory. Only literature and human stories can preserve the human experience of specific times, and pass it on to future generations.

10. What advice do you have for emerging writers?

Malaina: Even amongst the deadlines and revisions and copy edits, I think it is important to remember the “why” behind your work. Keeping those reasons close will allow you to create a final product that is reflective of who you are and what you wanted to build from the beginning.

Sola: Look at the world around you, not with indifference or detachment, but with curiosity. Read books that challenge you, that expose you to different views, that make you question your assumptions and beliefs. Understand the historical and political context of the authors you read, and how their work reflects or resists their times. Good books and good writing are never isolated or neutral; they are always in dialogue with something. Find what you want to say to the world; the writing will follow.

Sola Mahfouz was born in Afghanistan, and immigrated to the U.S. in 2016, to attend college. She is currently a quantum computing researcher at Tufts University Quantum Information Group. In her free time she is focusing on reading and studying different styles of fiction, as well as writing about the rugged homeland she has left behind. She lives in Boston, Massachusetts.

Malaina Kapoor is a writer who previously served as a Fellow at PEN America, where she advocated for international human rights, press freedoms, and election integrity. Kapoor was the producer of In Deep, a nationally syndicated public affairs radio broadcast program. She has received national awards for her poetry, personal essays, and short stories. She is currently an undergraduate at Stanford University and lives in Redwood City, California.

The PEN Ten Interview Series

Jillian Tamaki & Mariko Tamaki | The PEN Ten Interview

Megan Fernandes | The PEN Ten Interview

Bronwyn Fischer | The PEN Ten Interview

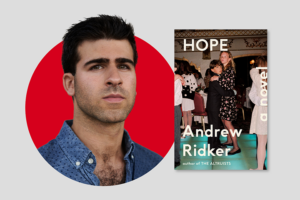

Andrew Ridker | The PEN Ten Interview

In a way, the structure of the novel reflects one of its primary themes: the desire to break away from one’s family, and the bonds that invariably pull one back.