Contributors H – M: Hamraaz • Hari Kunzru • Hemant Divate • Imraan Coovadia • Jacinta Kerketta • Jaideep Hardikar • Jeet Thayil • Jerry Pinto • Jhumpa Lahiri • Kai Friese • Karan Mahajan • Karthika Naïr • Kazim Ali • Keshava Guha • Kiran Desai • Kumar Ketkar • Madhusree Mukerjee • Manil Suri • Manisha Joshi • Manjula Padmanabhan • Manu Bhagavan • Maya Jasanoff • K R Meera • Meira Chand • Minal Hajratwala • Mira Jacob • Mira Kamdar

Hamraaz

Tremble

Some day soon,

you’ll be watching

a pair of tiny squirrels

chase each other

around a muddy park—

or you’ll hear a young girl

laugh as she rides

an oversized cycle, hard

through rain-soaked lanes—

and for a time you may

forget the fading light—

but later you’ll read

more friends have been charged

for reading namaz,

or that Hany Babu

is still in jail—

or you’ll see a brown kite

fly away with a squirrel—

and you’ll remember

the darkness and tremble.

—————

Like That Cat, or Our Constitution,

Sometimes precious things

disappear in a moment,

like the flash and bang

of a wedding cracker

or that cat you used to feed,

caught under a swerving bus;

but sometimes they slip away slowly,

like an early morning dream

where you know you left something

of great value in the train car

you see sinking in the river—

a box of old family photos,

perhaps, or the lipstick you took

from your grandmother’s table

on the day she died—

and you’re glad you’re safe on the shore,

but by the time you come fully awake

you cannot remember

where the train had been going,

what had broken the bridge,

or how many fellow travelers

now lie beneath rushing waters.

Hamraaz is a fictional character who writes poems about the dark times in India. Their work has been published in many places including The Penguin Book of Indian Poets, Rattle, nether Quarterly, The Wire, and The Alipore Post.

Hari Kunzru

I only met my great grand uncle, Pandit Hridaynath Kunzru, in the last year of his life. By that time he was completely blind, and I, a child of eight, was brought to him so he could ‘see’ me, which he did by brushing his fingers, very gently, all over my face. Later, I discovered that this former freedom fighter with the fluttering papery touch had, as a member of the Constituent Assembly, been one of the framers of the Indian constitution. He believed in an India that was tolerant, pluralist, and ruthlessly committed to the freedom of its citizens. He built civil society organizations because in a democracy there should be a counterweight to government power. He declined the Bharat Ratna1India’s highest civilian honor., because he thought such honors had no place in a Republic. On this seventy-fifth anniversary of Independence, I honor his principles, and his memory.

Hari Kunzru was born in London and lives in New York. His latest novel is Red Pill.

Hemant Divate

Translated from the Marathi by Mustansir Dalvi

We are Cursed to Speak

Speak, poet, speak!

Keep speaking to these hanging devils Or you’re done for

Look, it’s something o’clock or the other

The venom of religion stretches to infinity Out in the street, holy men everywhere

Hiding to target

In my mind, at least,

We come together, crush them Leave them behind

Shivering in the dark

It’s the business of poets To show unseeing crowds Rotting stories

Mired in riddles

Soaked in the ink of darkness

Should I speak, you ask?

To those who listen but do not hear Keep at it

You have to

Tell the deaf, dumb and blind

Tell the bhakts, herded like sheep

You have to keep telling

Until blinders are lifted from their eyes

All this telling will find its worth sometime And, in any case, who other than us

Can do this?

Let the truth be blown to smithereens

Let its smoke billow

Let the deaf see

Let the blind hear

Let the dumb sneeze

From the vacuous maws of their navels Let dirt be emptied

From their minds

For until the blind regain 20/20 vision Until the deaf can hear acutely

Until the dumb can scream

The telling cannot cease

It’s the job of the poet To keep speaking

We are cursed to speak

—————

Terror

I

sit

to

write

and

those

at

home

quake

in

terror

Hemant Divate is an award-winning Marathi poet, editor, publisher, translator, and poetry activist. He lives in Bombay. He has published seven collections of poems in Marathi and has been translated in many languages around the world. Mustansir Dalvi, who translated these poems, is a poet, translator, and editor. He has published three books of poetry, and translated Muhammad Iqbal’s poetry from Urdu to English.

Imraan Coovadia

Gandhi’s Houses

On May 27 1947, assessing the violence of partition, Gandhi wrote: “I am in the midst of a raging fire. Is it God’s mercy or the irony of fate that the flames do not consume me?” As close and eccentric a father to India as to his own children, his experience of communal killing was both anguish and a certain sense of invulnerability, a condition not so unlike those of us, India’s children and step-children, who watch the country’s arrival at a second slow-motion partition, supervised by the BJP: the destruction of Gandhi’s greater ashram. At the closure of the first ashram at Sabarmati in Gujarat, he defined the community, whether nation or ashram, as a mere house and confessed in a letter that “I have made it my profession in life to break up homes…I started doing this in 1891…ever since I have been doing nothing but that.” Moreover “I do not remember having ever felt a wrench in the heart in all these wild adventures.” We could call that spirit of joy, resistance, and creative destruction libertarian, if that word retained its meaning, let the same spirit guide us in resisting the massive, dour, purified, and homicidal house Prime Minister Modi is building across the subcontinent.

Imraan Coovadia was born to Indian parents in South Africa. He is the author of works of fiction and non-fiction and teaches at the University of Cape Town.

Jacinta Kerketta

Translated from Hindi by Bhumika Chawla-d’Souza

क्यों महुआ तोड़े नहीं जाते पेड़ से?

Why is the mahua not plucked from the tree?

Mother, why do you wait all night

For the mahua to fall?

Why not pluck from the tree

At once the mahua all?

Mother replies,

They grow in the tree’s womb all night

And when the time is ripe

Fall to the ground on their own

As the dewdrops soak them in the morn

We pick them and bring them home

When all night long the tree

Is writhing with pangs of birth

How could we shake a branch, tell me?

How could we pluck the mahua, say,

From a tree forcibly?

We wait for the mahua to fall,

For we love them, is all.

Jacinta Kerketta is an Adivasi poet and journalist. She writes in Hindi. Her poetry collections include Angor, Land of Roots and, most recently, Ishvar aur Bazaar. She has won multiple awards, including the Indigenous Voice of Asia Award in 2014. Bhumika Chawla-d’Souza is a translator in Bangalore.

Jaideep Hardikar

At the stroke of freedom, India chose to follow a secular state and vowed to turn her fractured and communal civil society on to a constitutional path.

Framers of the Constitution believed that ultra-nationalism can’t keep societies united. Civil cultures do. Secular constitutionality and egalitarian civil society are a prerequisite to co-existence and growth of a heterogeneous society as ours. Religion or markets can’t address polycentric problems of humanity. Fulfilling those ideas remains, alas, a dream. More difficult to achieve today.

At 75, India is steered by a regime wedded to religious and market fundamentalism and ready to shun communal harmony and non-violence to stay in power.

It’s the symptom of a far deeper malaise. Departing from the ethos of a just, liberal, and social democracy, a demographically young and impatient India is toying with ultra-nationalism, aided and emboldened by the rise and rise of benevolent dictatorship and egged on by a pliant media, a corrupt executive, a spineless judiciary, an inept legislature, collapse of institutions, and a non-existent political opposition. In an era marred by growing inequality, the anxieties plaguing our nation are but a manifestation of the many failings and fears of uncertainties.

Our freedom—the freedom to err as Mahatma Gandhi would say—is in peril.

Protecting that freedom and returning to the earnest constitutional path, a consensual form of democracy, calls for a resolute action from all of us who believe in a plural, secular and liberal thought, to bring a people back from the spell of majoritarianism and authoritarianism.

Jaideep Hardikar is a journalist and author of A Village Awaits Doomsday and Ramrao—The Story of India’s Farm Crisis.

Jeet Thayil

TWO GHAZALS

FEBRUARY, 2020

The climate’s in crisis, to breathe is to ache in India.

Too cold or too hot, we freeze and bake in India.

They police our thoughts, our posts, our clothes, our food.

The news, and the government, is fake in India.

Beat the students bloody, then file a case against them.

Criminals in power know the laws to break in India.

Pick up the innocent and lynch them on a whim.

Minorities will be taught how to partake in India.

Hum Dekhenge, the poet Faiz once said. But if you say it,

You’re anti-national. You have no stake in India.

Women and students and poets: they are the enemy.

Come here, dear, we’ll show you how to shake in India.

The economy’s bust, jobs are few, the poor are poorer.

Question is: how much more can we take in India?

When you say your prayers make sure you pick the right god.

Petitions to the wrong one you must forsake in India.

Jeet, if you don’t like it here, Pakistan isn’t far away.

If you want to stay, shut up, learn to make in India.

DECEMBER, 2020

Twenty-twenty is acuity of vision, a bane of the plague.

It’s the year we saw clearly the claim of the plague.

The poor and the powerless were first to be forgotten.

And last. How else do you play the game of the plague?

The corrupt and the cockroaches always will survive.

Home ministers too. Oh shame on thee, plague!

Mandelshtam’s joke about Stalin’s roach mustache:

It got him sent to the gulag, a stain on the plague.

Ferreira, Gadling, Dhawale, Gonsalves, Raut—

Hounded, imprisoned, driven insane in the plague.

Kalita, Narwal, Teltumbde, Wilson, Rao, Bharadwaj,

Babu, Sen, Navlakha, say each name to the plague.

Where did conscience go in India’s new gulag?

To the alley, to sell itself for fame in the plague.

Say nothing, hunker down, mask up, stay safe.

No jeet here, just your share of blame in the plague.

Jeet Thayil is the author of four novels and five books of poems. His essays, poetry and short fiction have appeared in the New York Review of Books, Granta, TLS, Esquire, The London Magazine, The Guardian, and The Paris Review. He is the editor of The Penguin Book of Indian Poets.

Jerry Pinto

1977. A cinema hall in Mahim, Mumbai. Amar Akbar Anthony is playing. It is a Manmohan Desai special, which means we, the audience, those who love Hindi films, were ready for a rollick. We did not expect to cry.

To those lucky people who have not seen AAA, as we learned to call it: A terrible rich man kills someone by mistake; he asks his loyal driver, Kishanlal, to take the blame and promises that he will look after the driver’s family and his three children. Kishanlal takes the fall, goes to jail and when he comes out, he finds his wife is dying of tuberculosis and his sons are starving. He goes to confront his boss and in return for his loyalty, his boss orders his henchmen to kill Kishanlal. He eludes them and jumps into a car full of gold bullion and comes home to find his wife has gone off to commit suicide. The goons are still in hot pursuit so he stashes the children for safety in a nearby park, in the shadow of a statue of Mahatma Gandhi and continues to take evasive action. His eldest son runs after the car but is knocked down, and left by the side of the road. A policeman takes the boy home, adopts him and names him Amar. The second boy is adopted by a Muslim tailor and named Akbar. The third child falls asleep in front of a Christian church and is adopted by the priests; he is Anthony. The boys grow up and one day, they are called to a hospital to give blood to a woman who is in need of it. They do not know it but they are donating blood for their mother.

Now, everyone knows that when you go and donate your blood, you fill a bottle and it is whisked off to the blood bank. But in Manmohan Desai’s magnificent and corny spectacle making, this could not be how we would see it. The three young men are seen lying down in a ward and each would declare his name as a nurse hooked him up to a blood donation line.

“Amar,“ declares the Hindu as his blood rises up, against the laws of gravity, to meet the blood of Akbar and Anthony. And then these three bloodstreams, conjoined, flowed down into the arm of their mother.

The man in the next seat began to weep. The whole theater was weeping together as a song underlined the message: Kya iski keemat chukaani nahin? (Will you pay your debt?) They got it. You don’t get India unless you have Amar, Akbar and Anthony, blood and blood and blood, paying their debt to the motherland.

I wept too. I was eleven years old.

At the end of the film, we all came out of the theater having cried and laughed and rejoiced when the three brothers are reunited in the end.

I used to say that the trope of three brothers separated at birth and reunited at the end was Hindi cinema’s way of thinking about Pakistan and Bangladesh. That we don’t make these films any more is perhaps our way of reconciling to the new political reality of the subcontinent.

I showed the film to a group of students recently. One of them said: “I’d really like to know what happened afterwards. Was Akbar circumcised by his Muslim father? Did Anthony remain a Christian?”

On bad days and there are so many of them, I know the answer to that one.

On days of hope, I cling to the promise/premise of those lines:

Anhonee ko honee kar de, honee ko anhonee.

Ek jagah jab jamaa ho teenon:

Amar, Akbar, Anthony

A rough translation of which would be: When the three of us, when Amar and Akbar and Anthony, get together, we make the impossible, possible.

Jerry Pinto is a poet, novelist, and translator in Bombay, and the author of several works of fiction, translations, and poetry, including Em and the Big Hoom. He received the Windham-Campbell Prize for Fiction in 2016.

Jhumpa Lahiri

Because I was born and raised outside of India, India, in its absence, took on even greater significance in my mind. I grew up with parents who, in missing India, sought out other Indians, and so my notion of an Indian community was always diverse. When they invited other Indian families to our home, in the small Rhode Island town where I was raised, I realized that India was an elastic container of individuals who spoke, ate, dressed, and prayed in different ways. These differences did not “enrich” an otherwise homogeneous India; they were India. In that sense, India seemed light years ahead of the United States, which was a melting pot in name but alienating and provincial in practice, at least from my perspective. Visits to Kolkata, a city that, as my mother liked to point out, welcomed all of India’s populations, only confirmed my perception that India’s relationship with The Other was built into its very fabric. The plurilingual aspect of India, in particular, both inspired and consoled me, for it insisted on the need for ongoing communication and translation. The co-existence of more than one language generates curiosity, calls for interpretation, and subverts any notion of absolute power. Unravel certain threads, or snip some strands away, and the conversation is lost; we are left with a frayed society, with imposed silence, with banal and baleful notions of nationhood.

Jhumpa Lahiri was born in London and grew up in the United States to Bengali parents. She won the Pulitzer Prize for her debut short story collection, Interpreter of Maladies, and is the author of three novels, including, most recently, Whereabouts, and two collections of short stories. She writes in English and Italian.

Kai Friese

Indians of my vintage are accustomed to a few signature cliches about our country: ‘a land of contradictions,’ a ‘raucous democracy.’ Chestnuts that have been invoked by everyone from Che Guevara to the U.S. State Department. But as the 75th anniversary of independence approaches, those backhanded, if affectionate, compliments sit uncomfortably with the spirit of a majoritarian and increasingly intolerant ‘new India’ where the raucousness of power seems to silence dissent. Meanwhile the ruling dispensation faces the challenging ironies of celebrating a national history most of which unfurled under the auspices of its political adversaries. The government has struggled valiantly to control the narrative by branding the anniversary with its own somewhat anodyne slogans. “Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav,” the official site informs us “means elixir of energy of independence; elixir of inspirations of the warriors of freedom struggle; elixir of new ideas and pledges; and elixir of Aatmanirbharta.”

I attended my first azadi event a few days ago: A global corporation was paying court to India and its government. The elixirs were flowing at a well-appointed bar in an enormous air conditioned gazebo, though they were briefly stilled as a minister ran through his garbled speech. I had one of the customary ‘the country is doomed and there’s no hope’ conversations one has grown accustomed to of late and felt like what they used to call a ‘champagne socialist.’ Until a costumed band drowned us out with songs of national integration delivered in the emotional register of a new car launch. My glasses fogged over when I fled outside which seemed somehow appropriate. Driving home, I braced myself for a salutary rebuke from the real India. But even the familiar figure of the friendly beggar at the traffic light had passed out for the night.

Kai Friese is a widely-published Indian journalist based in Delhi. These are his personal opinions.

Karan Mahajan

On India’s 75th, I find myself worried for my country. The fascist takeover of all aspects of public life is well-documented; but what is even more disheartening is the complicity of the majority. India is fast becoming a country of people who shout about their nation’s greatness even as it is laid to waste by pollution, corruption, disease, environmental degradation, overcrowding, violence. To wake to reality is too painful; it is far easier to lash out at minorities. On India’s 75th, I wish the people of India a clearer vision, and a sense of what they will lose if they refuse to see.

Karan Mahajan is the author of Family Planning, a finalist for the International Dylan Thomas Prize, and The Association of Small Bombs, which was shortlisted for the National Book Award, won the Muse India Young Writer Award, and was named one of the New York Times Book Review’s “10 Best Books of 2016.” Raised in New Delhi, Mahajan is an associate professor in Literary Arts at Brown University.

Karthika Naïr

Hisaab-Kitaab or Current Assets: The Nation at 75

—————

Pro Salute Patriae: August 2017

At seventy – mere ripple in the ocean, as

they sing, of human history – your skin now has

the sheen of a battle just begun, or living

metal, say, validium: youthful, ungiving,

a sheath impervious to tenderness and touch,

fresh breeze and clement rain, or warm earth, any such

element that could thwart the route – return, you insist –

to cosmic dominion, a sudden hallowed tryst.

At seventy, you ripple with anaerobic might —

chest a hypertrophied vault, limbs chiselled for a fight,

predisposed to setting your own lustrous head of hair

alight, somewhat vile and futile a form of warfare

even against vermin. Eyes and ears – on constant red

alert – appear within thighs and breasts and knees, forehead

and groin. But most ganglions, you decide, are suspect;

so, severed or suppressed, lest their signals misdirect.

At seventy, you rip and reconfigure brain

and heart, neural networks, the works, all to unchain

this enhanced, singular self that claims devotion,

unquestioned, from units of every persuasion,

tissue and cell and organ system. Cerebral

worth gets reassessed; lobes frontal and temporal –

meaning and memory – are deemed nonessential.

One-chambered hearts, ideally, more consequential.

At seventy, your arteries throb in full riptide,

as do the veins: both suffused with plasma, rage and pride,

red-hot and cold-white. Yet, blood too bountiful will seep

into marrow and tendon, skin and membrane, then sweep

across your newly-compressed heart like waves of basalt.

Fresh rules, too, must apply on feelings: doubt a dire fault,

so are hunger and humour and thirst; triumph’s the chrism,

and wild umbrage tagged your sharpest defence mechanism.

At seventy, you enjoy the ripple effect

of high, mutant power coursing through each perfect

cell, the scent of their allegiance, the deference

of peers. The losses, you scoff, are false reference,

minor, disposable fry — dead vacuoles, torn

ligaments, the damaged liver, a crushed neuron

or three or ten. You love the hashtags you trigger,

daily global headlines, the murmurs, the shimmer.

At seventy, there’s not a ripple of laughter nor

space for tears or regret or guilt. Compassion’s a chore,

and glory the sole touchstone you cherish. We’re strangers

now: you can’t recall me, and a dog in the manger

I’d be named if you did. Still, a wish on a birthday

is custom, and mine, although a chimera this day,

shall chime through time: be human, plural, or better yet,

an atoll, with reefs more varied than the alphabet.

Karthika Naïr, born in Kottayam and settled in Paris, is a poet, fabulist, librettist, and dance producer. She is the author of several books, including the award-winning Until the Lions: Echoes from the Mahabharata.

Kazim Ali

My ancestors came from Baluchistan to settle in Chennai and Vellore. During Partition, my mother’s family moved to the kingdom of Hyderabad and my father’s family went to Karachi. I was born in England and raised in Canada. Is a human a fixed point in time and space? Are we never meant to move? Or grow?

Anyhow, I am Indian, influenced by its culture, language, and spiritual systems. How did I, as a Muslim, chose to study yoga and Vedanta so deeply? Yoga has always been transnational and cosmopolitan: its origins are ancient, but its flowering came in 14th century Kashmir, when the Shaivite sages were engaged in deep interchange with the Persian and Arab world. Ideas from Islam and Vedanta cross-pollinated. Dara Shikoh, son of Shah Jahan, had the ancient yogic texts translated into Persian and Arabic and distributed across the Muslim world. Lal Ded and Kabir, one of them Hindu (itself a Persian word) and the other claimed by both Muslim and Hindu communities, wrote a poetry of spiritual humanism equally influenced by philosophies of both religions.

Did the poses of the surya namaskar come from the poses of the salaat or was it the other way around? Did the devotional kirtan transform into qawwali or did qawwali give shape to the musical elements of Vedic chanting? Does it matter?

What matters is that these spiritual practices and these peoples have been bound together and have been feeding one another for countless generations, bound together by language, by culture, by belief, and by blood.

Kazim Ali was born in the UK to Indian parents and lives in San Diego. He has published six volumes of verse and five works of fiction, besides non-fiction, translations, and edited an anthology. His new and selected poems will be released in the US and Canada in 2023.

Keshava Guha

The Republic of India was written into being—ours is a country made by writers. From Rammohun Roy to Ambedkar, the central figures of the 150 years of intellectual and social ferment that culminated in Independence and the Constitution were not simply people who used writing as a vehicle, but true writers of the highest class—of poetry, fiction, memoir, and above all of journalism. They quite literally believed that the answer to a book was another book: Lala Lajpat Rai’s was one of dozens of book-length replies to Katherine Mayo’s Mother India. Our Republic’s record, across governments, of treating books and writers with suspicion is a particularly tragic betrayal of our own history.

As we celebrate 75 years of freedom, one way of honoring the men and women who gave us that freedom would be to begin, at last, to reverse that betrayal. We could start by letting people read The Satanic Verses without restrictions.

Another would be to read them. Compared with the writings of say, the American Founding Fathers, our inheritance is far richer and immeasurably more relevant to today. From Vivekananda to Tarabai Shinde, from Ranade to Phule, they give us, paragraph by paragraph, a source of insight and invigoration that is inexhaustible, like Draupadi’s cooking pot. For all their differences, what they shared was a love of India that a century later still explodes off the page. That love manifests as deep pain at our collective sorrows and imperfections, and deep conviction in our collective capacity for improvement. We have never needed them more.

Keshava Guha was born in Delhi and raised in Bangalore. He is the author of the novel Accidental Magic.

Kiran Desai

Eight Haikus for Asifa, age 8

I

as if a girl is

evening blue and green that just

hovers a moment

before the night’s dark then falls

II

as if a girl is

what it takes to rape and kill

it takes a village

it takes a policeman

a temple custodian

a tax man, a son

who took the bus all

the way from meerut because

it takes a village

III

as if a girl is

a mother without a child

the moon still rising

IV

as if a girl is

a bad luck curse parents flee

over this mountain

the next and over

the border to lose their names

so we can’t find them

V

as if a girl is

snow obscuring mountains and

lies covering truth

VI

as if a girl is

chinar leaves or grass marked red

bloodied by murder

VII

as if a girl is

a ghost making a devil

of us all

she haunts

VIII

as if a girl is

only eyes—that’s all that’s left

warning—don’t forget!

Eight year old Asifa was gang raped and murdered in a temple in 2018, Kathua, Kashmir. When she died she became a symbol of the hate that has overwhelmed today’s India. But she also became India’s daughter, the daughter of us all.

India may be in darkness, but we will forever remember your light, Asifa!

Kiran Desai is the author of Hullabaloo in the Guava Orchard and The Inheritance of Loss. Among her honors are a Guggenheim, a National Book Critics Circle Award, and a Man Booker Prize.

Kumar Ketkar

George Orwell would be the right person to describe the current condition of democracy in India. Superficially, all the “forms” of democracy are there. There is Parliament, there is judiciary, there is Reserve Bank of India, there is the vast expanse of the print and electronic media, there is the Indian Administrative Service, there is the Enforcement Directorate, the Income Tax Authority, there is the Central Bureau of Investigation and, of course, there is the Election Commission. All these institutions were the pillars of sovereign democracy. Or that is what we believed. Looking at the current conditions it appears that our belief was misplaced. These so-called “independent institutions” have surrendered their autonomy, their independent approach and even courage to stand up to the authority. Not only do they wait for directions from the Modi administration, they literally prostrate before the Prime Minister. Many of these illustrious leaders and heads of the institutions publicly state that Narendra Modi is an incarnation of Lord Rama, or Krishna, or the Supreme God of all Gods. And now he has become “Vishwaguru” who has descended to this planet to liberate the world from injustice, oppression and sins.

Even as these words are being spoken, some Muslims are killed, some tortured, or their businesses boycotted. Some Dalit communities attacked, the people of Kashmir are virtually under constant surveillance or threat, and those who dare to write or show the atrocities are arrested. The politicians who confront the government are charged with some offense or the other, framed on cooked up charges, or overplayed/prosecuted? over minor misdemeanors.

No wonder, from the corporate class to the media, from sincere bureaucrats to honest judges, from various NGOs to litterateurs and filmmakers, many are living in the shadow of terror.

All this is camouflaged in the glorious words of democracy and even references to human rights and Gandhian values. That is why Orwell would have been able to write about the current condition of democracy. But it appears to me that even Orwell would have found no words to express himself fully.

Kumar Ketkar is a journalist and editor for nearly fifty years, of English and Marathi dailies. Author of 10 Marathi books and regular contributor to a few English periodicals, he is Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha, India’s Upper House. He lives in Mumbai.

Madhusree Mukerjee

15 August, 1942. Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel, Maulana Azad and thousands of other freedom fighters are in prison. More than 90,000 people will be arrested and up to 10,000 killed as the Quit India movement is crushed. Kasturba Gandhi and Mahadev Desai will die in prison. Millions will perish of hunger. India is an occupied and hostile country, says a British general. Virtually no one—not the rulers looting the country’s wealth, nor the people crushed under their weight and induced to fight one another instead of their exploiters—can imagine, in this darkest of dark times, that in a few years the land will be free.

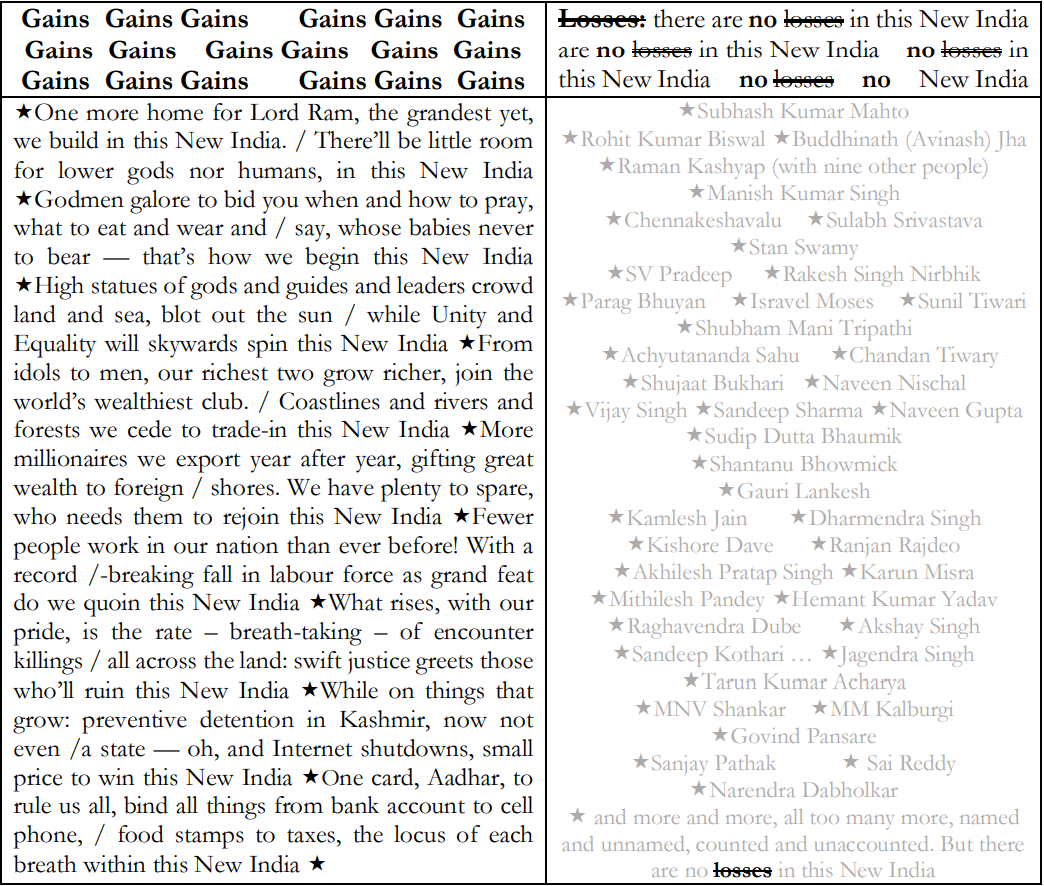

15 August, 2022. Anand Teltumbde, Hany Babu, GN Saibaba, Gautam Navlakha, Arun Ferreira, Shoma Sen, Surendra Gadling, Rona Wilson, Mahesh Raut, Vernon Gonsalves, Khalid Saifi, Meeran Haider, Sharjeel Imam, Umar Khalid, Aasif Sultan, Siddique Kappan, Sanjiv Bhatt, Teesta Setalvad and countless other freedom fighters are in prison. So are thousands of Muslims, for being Muslim, Dalits, for being Dalit, and Adivasis, for living on mineral-rich land that billionaires covet. Stan Swamy is dead. Gauri Lankesh, Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare, MM Kalburgi and far too many other truth tellers—rural reporters, Right-to-Information activists—are also dead. Murdered. And innumerable people whose crime was to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Three-quarters of Indians are malnourished and being induced in their desperation to turn upon one another instead of their exploiters. Just one of their rulers is the world’s fourth-richest man.

India is once again an occupied and starving country. It’s hard to imagine, in this darkest of dark times, that the country will soon be free. But history repeats. And great evil always falls to great courage.

Madhusree Mukerjee is the author of Churchill’s Secret War and The Land of Naked People. She is a Guggenheim awardee and serves as a senior editor at Scientific American.

Manil Suri

In 2007, on the 60th anniversary of India’s independence, I wrote an essay for India Today on their commemorative theme, “What Unites India.” The gist was that the country’s citizens are so diverse in terms of religion, caste, class, culture, language, skin tone, and so on, that they find themselves pulled in different directions by the different groups to which they belong. These competing allegiances prevent radically divisive movements from snowballing, thereby helping keep the country together.

Now, fifteen years later, a wave of hatred, as virulent as it is nakedly political, is sweeping the land. People are being asked to support attacks on secularism, on free speech, on the constitution itself, to supposedly further their own self-interest. While the current situation is dismaying, let’s remember the population has surmounted past upheavals such as Partition, the Emergency. What I wish for, for India’s 75th birthday, is that her citizens renew links they might have ignored, rediscover their divergent affinities, so that the push and pull of attracting and opposing forces restores the equilibrium of the country’s fabric.

Manil Suri was born in Mumbai and is a mathematics professor in the United States. He is the author of three novels on India, including The Death of Vishnu, which was long-listed for the Booker Prize in 2001, and a non-fiction book on mathematics.

Manisha Joshi

When it comes to defining a country as vast as India, it is best to think of her as a small village. I often remember the village of my childhood where I sometimes used to eat at our neighbor Shirin’s house. As per the Muslim tradition we all used to circle around a huge aluminum thali (platter) to break bread together. It’s been twenty years living away from India but I still miss that rare comfort of interdependent communities in an otherwise paradoxical country.

India of my mind has always been that one imaginary morning where the doorbell of my house keeps ringing and dhobi, doodhwala, sabjiwala, paperwala, cablewala (washerman, milkman, vegetable vendor, newspaper vendor, cable tv channel provider) and many others come and go, like invisible guests in my life.

The boundaries between the private and the public are so easily blurred in India that the idea of individualism still remains alien. What I really like about Indian society is that there is always a conversation taking place in some form or the other and there is always some room for negotiation.

Manisha Joshi worked as a print and television journalist in Mumbai and London and now lives in California. She has published four collections of Gujarati poems Kandara, Kansara Bazar, Kandmool, and Thaak.

Manjula Padmanabhan

Like a banyan tree, India will endure.

The original tree has died, of course. The one that you and I loved, praised, and revisited in dreams—yes, that one has gone.

But the living forest of ideas, stories, tastes, sounds, and scents that sprang up around the original tree? It lives on. It thrives.

We continue to call it India, even though it is unrecognizable.

Meanwhile, with every passing year, our memories of that original tree grow sweeter and more vivid. Already, what we remember is better than it ever was.

Let us be grateful that we can never return.

Manjula Padmanabhan was born in India in 1953; currently living in Newport, Rhode Island. She is an award-winning playwright, artist, illustrator and writer. She is the author of 14 books of prose and plays, has illustrated over 20 books for children and till recently published SUKIYAKI, a weekly comic strip.

Manu Bhagavan

India’s Most Significant Contribution to the Modern World

In 1952, former US First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt traveled to India, where she was received by the high-flying diplomat Madame Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, then a Member of Parliament. Both were among the most famous and acclaimed women in the world at the time. Over the previous decade, they had developed a close relationship based on mutual respect and admiration. Madame Pandit, as she was internationally known, interviewed Mrs. Roosevelt for a national radio broadcast and asked her what she thought was the most significant contribution to the global community her newly independent country might have recently made.

India, Mrs. Roosevelt responded immediately, stood for democracy, equality, and justice. “I think your elections in the first place was a great contribution and I also think the decision of India to have a Secular State, a State in which all religions were recognized and tolerated and still a Government that was not a Government primarily motivated by a particular religion, was a very great contribution perhaps, because that is the way we feel in [the United States]… and I think the other thing which has impressed me the most is your legislation against the caste system. We all know, of course, the legislation alone does not accomplish everything we want to accomplish, but it has to be there as a background and those of us who care about [such] questions will then be able to work with something to help us do the work. I believe that from my point of view those are the three big contributions that India has made.”2Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit interview with Eleanor Roosevelt, All India Radio, 22 March 1952, Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project, The George Washington University, erpapers.columbian.gwu.edu/radio-interview-vijaya-lakshmi-pandit-march-22-1952. Last accessed 17 July 2022.

Manu Bhagavan is a historian who lives in New York. He is the author of The Peacemakers and a forthcoming biography of Madame Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit.

Maya Jasanoff

On the 75th anniversary of the nation’s independence from the British Empire, a statesman addressed his countrymen. The republic “has met dangers, and overcome them; it has had enemies, and conquered them; it has had detractors, and abashed them all… and the world beholds it… with profound admiration,” said Daniel Webster, celebrating the United States in 1851—which championed equality while enslaving millions and waging wars of genocide and conquest. Ten years later, the tension between American ideals and practices culminated in civil war. As India turns 75, statesmen will celebrate democracy in a nation tilting, not for the first time, toward authoritarianism. The republic’s founding ideals are disdained by a BJP régime that throws over secularism for strident Hindu nationalism; traduces freedom by intimidating and censoring its critics; and winks and nods as a country once associated with non-violence has become notorious for beating, lynching, and rape. Ten years from now, can the ideals even survive to be fought for?

Maya Jasanoff is the Coolidge Professor of History at Harvard and the author of the prize-winning books Edge of Empire, Liberty’s Exiles, and The Dawn Watch.

K R Meera

Independence Day is something personal to me. My grandfather was a freedom fighter. I grew up with the pride of knowing that I too am a part and partner of the legacy of a greatness named India.

My India is the promised land where every single citizen sings: “where the mind is without fear and where the head is held high.” My India is the paradise of the ultimate freedom of everyone’s thoughts and expressions. My India is characterized by non-violence and Ahimsa. My India is deep rooted in pluralism, diversity, and secularism. My India is where wisdom prevails, scholarship is treasured, human dignity is ensured, justice is endorsed. I can’t imagine India in any other way. My India is a living entity, growing within me, through me and out of me, forming an ecosystem. My India is a happy country. A very very happy country.

K R Meera was born in Kerala and lives in Kottayam. She is the author of ten novels, nine collections of short stories, and three memoirs, all written in Malayalam.

Meira Chand

No greater symbol of non-violence exists than the name of Mahatma Gandhi. My English/Swiss mother, newly married to my Indian father, garlanded Gandhi, during his visit to London in 1931. Hope for an enlightened and peaceful Independent India filled those years between the two world wars. Indian Independence came but was followed closely by the man-made horrors of Partition, with experiences of violence that damaged my Indian husband and multitudes more, for life. In the few years I lived in India in the early 1970s the country struggled before a fork in the road. The Emergency came, its vicious repression bringing new meaning to the role of political power in India. Today violence, to those who politically command it, is seen as an expediently easy tool to serve egoistic agendas, shaping India in frightening new ways. Yet the opportunity for peace always exists. Men who seek an expansion of the human spirit, like Gandhi, are rare, but their names live on forever, beyond megalomaniacal autocrats. Peace, and enlightened ideas, are what humanity consistently remembers. Observing India’s sad and horrific shift towards bigoted aggression, it is ironical that historically Gandhi’s legacy places India forever as a unique example of the human power of non-violence.

Meira Chand’s multi-cultural heritage is reflected in her nine novels, including, most recently, Sacred Waters. An earlier novel, A Different Sky, was long-listed for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award and on Oprah Winfrey’s reading list. She lives in Singapore.

Minal Hajratwala

Today we jubilee! 75 years since that solemn moment when the soul of our nation, long suppressed, found utterance. Ah! how we ousted those oppressors who wreaked such outrages: kidnapping of 1 million into indenture, massacre at Jallianwala Bagh, lathi charge at Dandi, famine of Bengal. That midnight we awakened to triumph. See how we have birthed a nation of gang rapes and acid attacks, wars to sever every border, endless caste and communal atrocities, and the ever-greater concentration of wealth in the hands of an ever more brutal elite! Today let us set off fireworks to consecrate the yajna, sacrifice-by-immolation of every institution of civil society—free press, independent judiciary, rational system of education—on the altar of Hindutva. Let us clasp hands across our tech companies and casteist samaj halls and sex-selection clinics and construction high-rises and bollywood-mafia theaters throughout global Greater Bharat. Let us carry on our tryst—a tear for every eye!

Minal Hajratwala is the author of three books of non-fiction and poetry, editor of an anthology of queer Indian writing, and founder/guiding coach of the Unicorn Authors Club.

Mira Jacob

“My parents called me their good luck baby,” my mother tells me. She was born in May of 1947, passed from person to person in the triumphant march toward Chowpatty3A popular beach in Bombay. that August. The rest of the details—the thousands of shining faces, the singing, her fat body buoyed by so many strangers—are not as much memories as her inheritance of a dream, one she folded into neat squares and brought to America. But now. But now. “What is happening?” she whispers. We feel it rising through the silences on the phone calls back home, the panic tucked into banalities. But what else can they say? What can any of us say? We look outside and find the dark and rising tide our own horizon. Our questions come with it, urgent and useless. Where is the safer ground? What turns a dream back into the body’s memory? What else will it take for us to remember how to cradle each other’s children, to carry them toward a brighter future?

Mira Jacob is a best-selling author, illustrator and cultural critic. Her memoir, Good Talk was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle award, longlisted for the PEN Open Book Award, and named a New York Times Notable Book. Her novel, The Sleepwalker’s Guide to Dancing, was a finalist for India’s Tata First Literature Award.

Mira Kamdar

Young India, you held such promise. Dreaming of your freedom, my teenage grandfather left home to join the Mahatma on the banks of the Sabarmati in the 1920s. Decades later, my Danish-American mother discovered a newly independent nation full of hope, and fell in love with an Indian man. Color was no bar. Caste was no bar. Religion was no bar. Now, religion is a bludgeon wielded by a Hindu nationalist government that has hijacked the India of my freedom-loving grandfather’s dreams. How I mourn it. How so many of us ache remembering a country where, despite occasional communal riots, hungry children with distended bellies, women married against their will—all this, and more was true—people were largely free to express their own minds without fear. Fear is everywhere now. A journalist can be thrown in jail for a tweet. Writers learn at the airport that they are no longer free to travel because what they have written has displeased. Still, the bravest persevere. We must not let them down. We must not give up on the dream of a free India. In a world slipping toward totalitarianism, it is the dream of freedom everywhere.

A former member of the New York Times Editorial Board and a contributor to leading publications around the world, Mira Kamdar is the author of four books. She lives in Paris.

Jump to: Introduction to India at 75 | Contributors A – G | Contributors H – M (top) | Contributors N – R | Contributors S – Z