Nobel Prize to Dmitry Muratov is a Sign that the World Should Unite to Confront Kremlin’s Foreign Agent Law

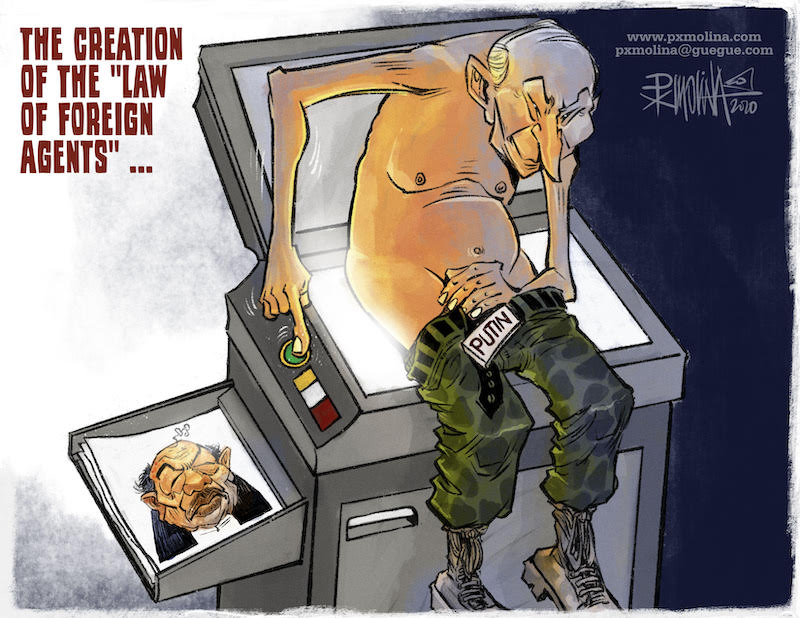

Illustration by Pedro X. Molina

The October 8 awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov, who lead independent news outlets in the Philippines and Russia, is an important step by the Nobel Committee to acknowledge the unprecedented crackdown on independent media by authoritarian regimes. Two journalists leading independent media in different parts of the world were chosen to prove the point that this trend is relevant not just for one country but around the world.

Another similar trend against independent media deserves equal recognition: the use of “foreign agent” laws. Russia was the pioneer of this tactic, passing its “foreign agents,” or “Putin’s law” as it’s referred to outside of Russia, in 2012.

The law gives the government the authority to label as “foreign agents” organizations and people who receive funding from abroad and whose actions are considered to be political activism. Those listed as such are obliged to present themselves as foreign agents, to label their products or speeches on television, radio, and online accordingly, and to report to the Ministry of Justice about their activities and spending. In the nearly 10 years since the law’s passage, 56 organizations and 19 individuals have been labeled as foreign agents. Most of the affected news outlets lost their funding as a result, and at least two had to shut down entirely.

Russian authorities have wielded the foreign agent law with growing impunity, particularly recently, in anticipation of the local parliamentary elections in Russia. Journalists in Russia joke darkly that they wait with a sinking heart for each Friday, when additions to the list will be published. Media organizations and journalists are not the only targets; just recently, Tatiana Voltskaya, a poet, journalist, and a member of PEN St. Petersburg known for her civic poetry criticizing the regime, was also labeled a foreign agent.

As demonstrated by the Nobel Committee’s awardee selection, the attempted silencing of media and journalists by authoritarian regimes is a global issue. The same is true for the foreign agent law. As Coda Story described in detail in a recent piece, Nicaragua, Belarus, Poland, Hungary, and Egypt are using this element of Putin’s playbook to persecute independent voices. The list is growing, as evidenced by the draft law in Turkey, and threatened action against Coda’s journalist Oliver Bullough by Angolan authorities.

So the award comes at the right time. The hope is that it will raise alarm to an urgent cause, inspire increased funding for independent journalism and the protection of journalists, and give journalists around the world reassurance that they are not alone in their fight to defend the truth. But this should be just the beginning.

If the Kremlin is allowed to keep using the “foreign agents” law to repress and discredit dissenting voices, this encourages anti-democratic forces in other countries. The international community must respond more robustly to this growing threat than it has thus far. Democratic governments should unite in supporting and protecting independent media. International organizations and their representatives, such as Special Rapporteurs and other leaders focused on freedom of the media and freedom of expression, should draw upon the principles enumerated in relevant Joint Declarations and come forward to decry “foreign agents” laws and the abusive tactics of authoritarians to silence the voices of media. And all should work together with the general public, as we all—no matter our affiliations—benefit from the work of independent journalists to uncover truths and ensure the public’s right to know.