By: Natalie Green

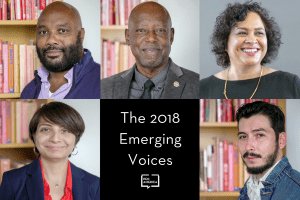

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week PEN America’s Los Angeles Program Coordinator Natalie Green speaks to the 2018 Emerging Voices Fellows: Jubi Arriola-Headley, Ron L. Dowell, Natalie Mislang Mann, Angela M. Sanchez, and Francisco Uribe. The 2019 Emerging Voices application is now open, and if you’re in LA, join us for the 2018 cohort’s Final Reading on August 3 at the Moss Theater.

1. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity”?

Everything we do or don’t do as people is shaped by identity, I believe. I’m an urban black man who has lived in segregated Los Angeles all of my life. That reality influences what and how I write. The neighborhoods I’ve lived in, access to art, schools and churches attended, and where we shopped contributed to identity. Even though I’ve been all over the world, my stories remain wedded to my experiences living in L.A. I write a lot about Compton, Watts. Hopefully, I challenge stereotypes and show what can happen when opportunity meets motivation. As I continue to grow and evolve, my writing should too.

—Ron L. Dowell

2. In an era of “alternative facts” and “fake news,” how does your writing navigate truth?

And what is the relationship between truth and fiction? The Aesop fables and Grimm’s fairy tales I read as a kid stuck to my brain into adulthood, which is probably why I enjoy writing urban fantasy. Fairy tales told many truths with graceful and direct metaphors (“Don’t trust the fox telling you the well water is the best tasting in the world.” “Collaring a cat with a bell is a great idea, but no mouse wants to do it.”). Our modern-day setting is as ripe as any for a supernatural or a speculative element to address topics from socioeconomic disparities to immigration and belonging. And sometimes, it feels like magic makes more sense than reality.

—Angela M. Sanchez

3. Writers are often influenced by the words of others, building up from the foundations others have laid. Where is the line between inspiration and appropriation?

Artists, in general, learn from copying those who came before them. Eventually, they become skilled enough and want to imitate. A good imitation can be a nice way to pay homage and honor those who inspired them. At some point, however, they themselves want to be heard because their voices have matured. It’s appropriation when an artist tries to pass off someone else’s distinct voice as their own without shedding light on the history of how that voice was formed.

—Francisco Uribe

4. “Resistance” is a long-employed term that has come to mean anything from resisting tyranny, to resisting societal norms, to resisting negative urges and bad habits, and so much more. It there anything you are resisting right now? Is your writing involved in that act of resistance?

I feel like I’ve spent my entire lifetime resisting. Resisting becoming my father. Resisting becoming a stereotype. Resisting becoming a statistic. I wonder, though, whether resisting is the same thing as resistance. Resistance, to me, implies more—a meaningful, proactive, and concerted pushback against the tyranny of silence, oppression, what have you. Sure, I write poetry, and writing poetry is inherently a political act, but when I think resistance I think Harriet Tubman, I think Black Lives Matter, I think teachers striking in West Virginia, I think 17-year-olds organizing “die-ins” in grocery stores. In other words, I think (just short of) revolution. But what I’m asking is—is poetry enough? Not likely. I’m constantly worrying myself about what more I can be/should be/need to be doing. All I know is, I need to do more.

—Jubi Arriola-Headley

5. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

I think the threat to free expression is a manifestation of a consciousness that exists in fear. The fear: Those holding powerful positions need to make room for diverse voices. Voices that yearn for space to breathe and to be unsilenced. I know how it feels not to be able to take a breath. As a teenager, I stopped writing. My parents didn’t see my creativity as an emotional outlet, but a means to dig for information. When I realized that what they uncovered could be used against me, I stopped until I couldn’t stop any longer.

—Natalie Mislang Mann

6. What’s the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words?

“I am a poet.”

—Jubi Arriola-Headley

7. Have you ever written something you wish you could take back? What was your course of action?

Yes. And what was my course of action? Not to talk about it.

—Francisco Uribe

8. Post, stalk, or shun: What is your relationship to social media as a writer?

All of the above. Memory feeds sometimes can be a memoirist’s friend.

—Natalie Mislang Mann

9. Can you tell us about a piece of writing that has influenced you?

Dr. Seuss’ Horton Hatches the Egg. It’s a cute picture book about an elephant that devoutly sits on an egg, which ultimately hatches to look like a smaller version of himself with wings. It’s also the book that my dad read to me to explain being a single father. It’s the simplest stories that offer so much meaning.

—Angela M. Sanchez

10. Can you share with us something you’ve learned about your writer-self during the past seven months as an Emerging Voices Fellow?

I’m just as good as anyone else. I don’t need to be George Saunders, Octavia Butler, Jhumpa Lahiri, or Raymond Carver. I’ll try to be just as good and as great as them, but I’ll be me.

—Ron L. Dowell