Freedom to Write Index 2022

PEN America Experts:

Managing Director, PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Center

Director, Writers at Risk, PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Center

Program Director, PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Center

Program Director, Advocacy and Eurasia

Manager, Research & Advocacy, PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Center

Program Manager, PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Center

Introduction

In May of 2022, at the PEN America emergency writers congress, Salman Rushdie spoke about global threats to human rights and democracy, including Vladimir Putin’s assault on Ukraine, and said:

“It has been said, I have said it myself, that the powerful may own the present but writers own the future, for it is through our work…that the present misdeeds of the powerful will be judged…We must understand that stories are at the heart of what is happening, and dishonest narratives of oppressors have proved attractive to many. So we must work to overturn the false narratives of tyrants, populists, and fools by telling better stories than they do.”

Three months later, when Rushdie was brutally attacked on a stage in Chautauqua, New York, in August 2022—more than three decades after the Ayatollah Khomeni issued a fatwa against him for his novel, The Satanic Verses—it served as a devastating reminder of the perils writers face for having the audacity to put their ideas, their creative vision, and their stories to paper. A reminder of the ways in which the powerful may attempt to silence words that can inspire people to think beyond the boundaries those in power would draw. But Rushdie has also embodied—in this work and his life—the ways in which writers’ words persist, and how writers themselves refuse to be silenced. Writing, wherever it occurs, is an act of fearlessness, of risk-taking, and of defiance. And in 2022, writers from Myanmar to Iran, from Ukraine to China, have demonstrated that courage, even in the face of brutal attempts to silence their voices.

In 2022, the state of free expression globally remained perilous. Yet the world also witnessed many courageous acts in defiance of repression, and in two countries in particular, the human will to assert demands for freedom, even in the face of shocking brutality. The people of Ukraine have demonstrated powerful, tenacious resilience since Russia’s brutal invasion began in February 2022, defending their land, but also their culture and their individual stories. And in Iran, women have led a diverse, dauntless protest movement to demand their rights, shaking the very foundations of the regime. In these and many other countries, writers have played an essential role, giving voice to public demands for freedom, democracy, and justice.

In March 2022, Volodymyr Vakulenko was abducted by Russian-affiliated forces and, months later, found killed in a mass grave. He wrote about life in Ukraine under occupation in a diary, which he buried before his abduction. (Photo by Maria Lysytska-Beskorsa)

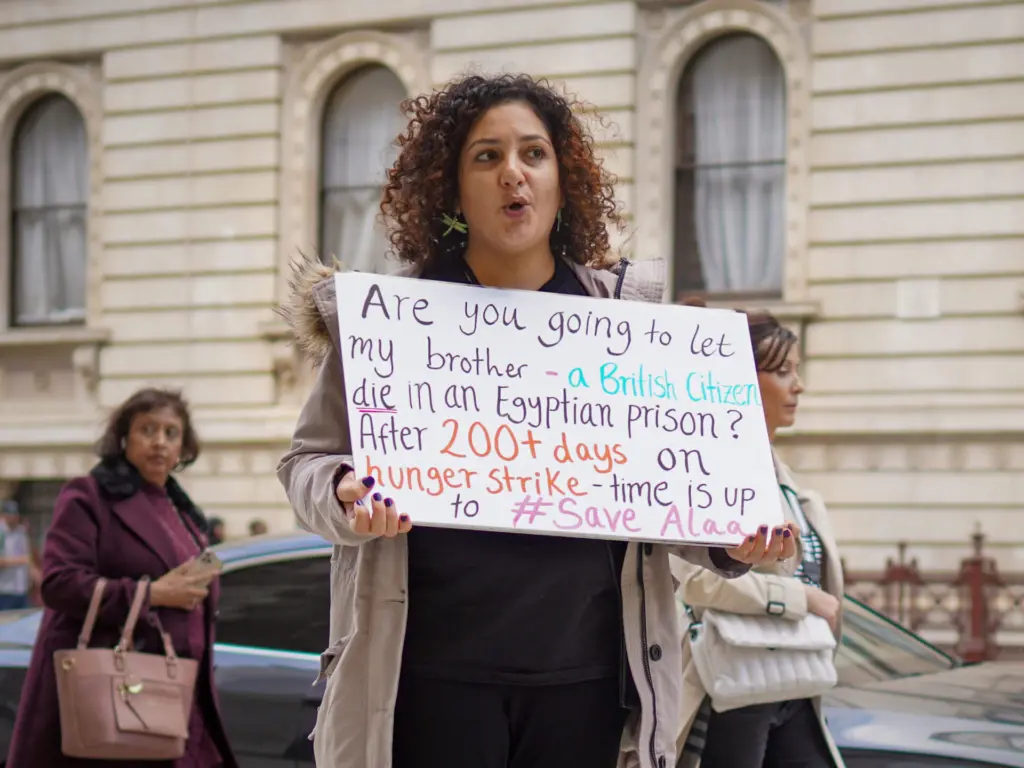

They have also paid the price. In Ukraine, poet and children’s book author Volodymyr Vakulenko was abducted from his home by Russian occupying forces in March, 2022; not until November would his body be identified as among those in a mass grave, unearthed after the liberation of Kharkiv. In Iran, women writers and poets have been detained frequently during the protests, often held for short periods of time, but sometimes repeatedly, and subject to mistreatment and torture. In January 2022, Iranian writer Baktash Abtin—jailed for his advocacy in defense of free expression—died of COVID-19 while in state custody, after the government delayed providing him the medical care he needed. In Egypt, blogger Alaa Abd El Fattah underwent a months-long hunger strike to protest being denied access to bedding, sunlight, exercise, and reading material for over two years. And in at least 36 other countries, writers have been locked up for exercising their freedom of expression.

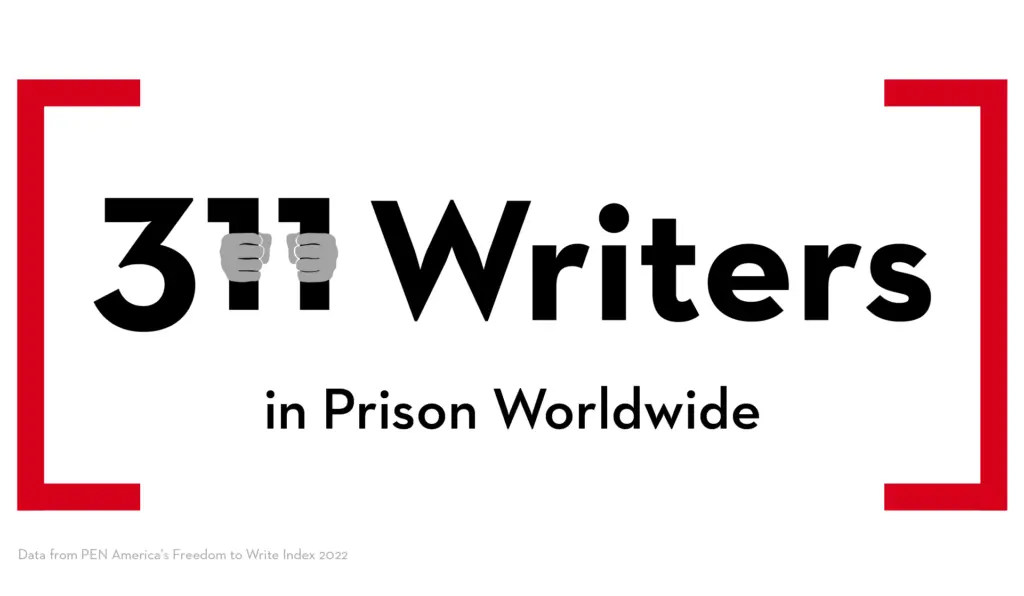

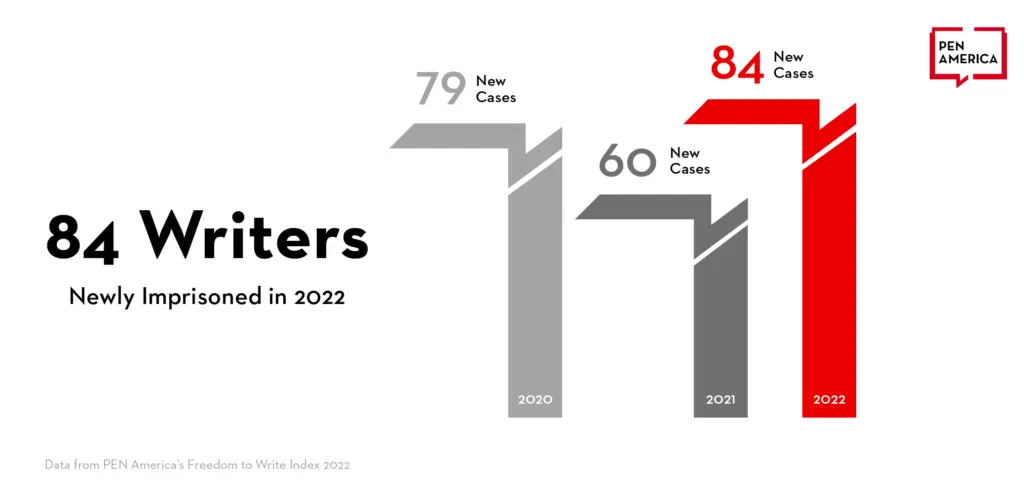

The Freedom to Write Index tracks the detention and imprisonment of writers, and in 2022, 311 writers were detained or imprisoned around the world for their writing or otherwise exercising their freedom of expression. That includes 84 new cases of writers put behind bars, many of which occurred in Iran, where writers have long been particular targets of the regime, but especially so during this past year’s “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests.

Unjust imprisonment deprives writers of their most fundamental rights, and often of the freedom to write, as well. Some writers are able to continue their work from prison, often sneaking their writing out to ensure their voice can still be heard. Elevating the words of those imprisoned for their writing is an essential act of solidarity and defiance. But prison can also severely constrain the ability of a writer to create new work.

And when a repressive regime puts a writer behind bars, that individual is not the only one to whom they are sending a message. Imprisonment is also a tool of intimidation wielded against the broader literary and cultural community of a country, intended to spark fear and to make writers question what they write, or whether they should write at all. The threat of arrest acts as a sword of Damocles, and can have a chilling effect on literary output, publishing, and even what writers talk about in public.

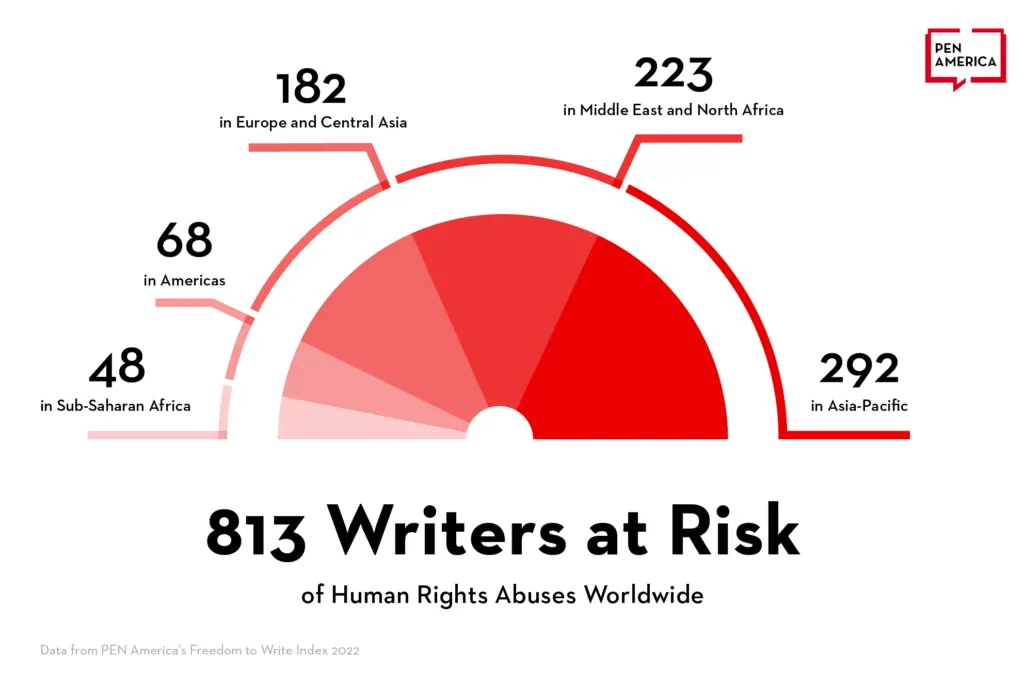

Imprisonment is also just one form of repression wielded in an attempt to intimidate and silence writers. PEN America’s Writers at Risk Database documents the cases of 813 writers who are facing a range of attacks, from surveillance, coordinated defamation and disinformation campaigns, and burdensome legal cases, to physical and online harassment, travel bans, death threats, and forced exile.

These attacks on writers are often part of a larger effort to repress independent culture, and independent thought itself. Last year PEN America documented the Russian campaign of cultural erasure occurring as part of the war in Ukraine. In China, virtually all aspects of cultural production are under the control of the state, and engaging in independent creative work involves grave risk. At the same time, alarming echoes of such campaigns have been seen across the U.S. in the past year as well, with the devastating rise in book bans across the country, and efforts to legislate what can and cannot be taught or even discussed in classrooms.

When the dictators and despots of the world target writers for their novels, their poems, their essays, and their songs, they only affirm the power and influence those works hold. They show us the truth of Rushdie’s words, that so much of the global battle today for democracy, truth, and freedom is about a struggle for narrative power, a struggle over who will tell the truth of the past, and who will offer the world a more appealing vision of the future. And when governments see fit to silence writers, it tells us they view ideas themselves as a threat—something that must be recognized as a warning sign for the state of free expression and democracy.

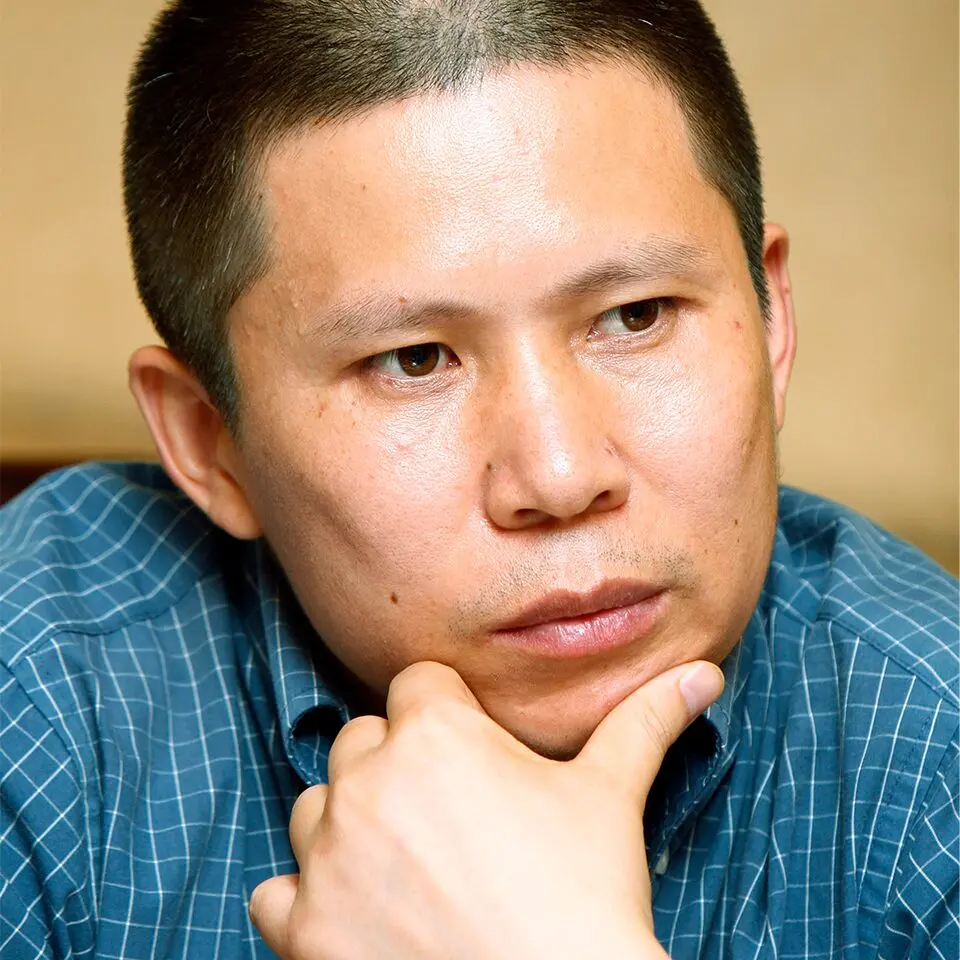

In April 2023, Chinese writer, legal scholar, democracy advocate, and 2020 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award honoree Xu Zhiyong was sentenced to 14 years in prison, after being detained since February 2020. As he described it, in a statement dictated before his sentencing: “I’m charged with ‘subversion of state power’ for expressing my desire for a beautiful China and for calling on Chinese to become real citizens.”

Xu is a writer and intellectual whose love for his country has inspired him to call for change, and to demand for its people the opportunity to realize the promise of freedom. His case is a resonant example of the potency of the written word, and of the lengths to which repressive governments will go in their attempts to silence a single, powerful voice. But Xu also reminds us that such repression is itself a sign of weakness; that, as Rushdie said, it is writers who own the future, and that hope cannot be contained within prison walls.

Xu’s statement went on: “I’m proud to suffer for the sake of freedom, justice and love…I don’t believe freedom can be forever imprisoned behind high walls. And I do not believe the future will forever be a dark night without daybreak.”

The writers who summon the courage to raise their voices, who offer a vision of daybreak—no matter the risk—demand our solidarity and our defense.

The Global Picture

Eighty-four writers were newly imprisoned in 2022, bringing the number in custody for exercising their free expression to 311. These writers, academics, and public intellectuals in 36 countries—in all geographic regions around the world—were unjustly detained or imprisoned in connection with their writing, their work, or related advocacy. The number did not change from 2021, but represents a steady increase from 2019 (263) and 2020 (286).1The compiling of the data for the Index is an ongoing process and PEN America adds cases retrospectively. Thirty-four cases were added retrospectively to the 2021 Index and included individuals who were imprisoned as of 2021 , but whose imprisonment only became known to PEN America while we were compiling the data for the 2022 Index. While such cases occurred in 12 countries, just under half were found in two countries, China and Saudi Arabia.

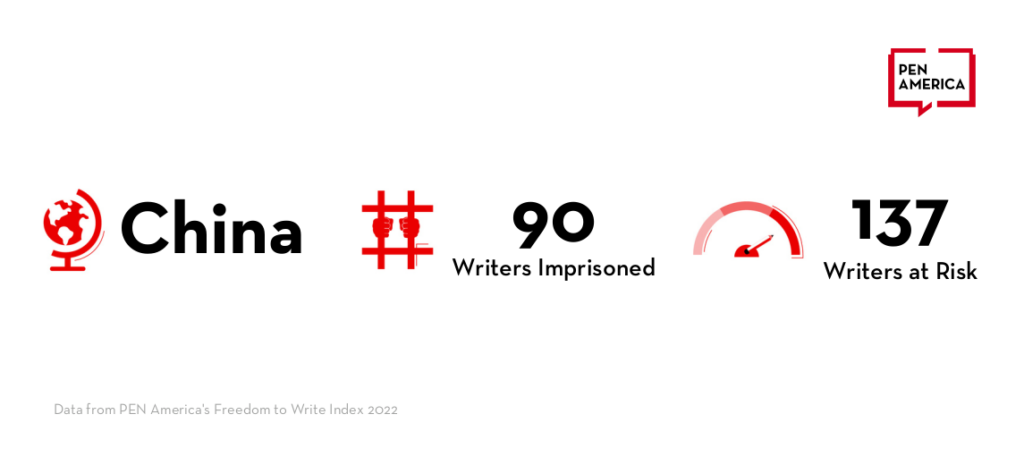

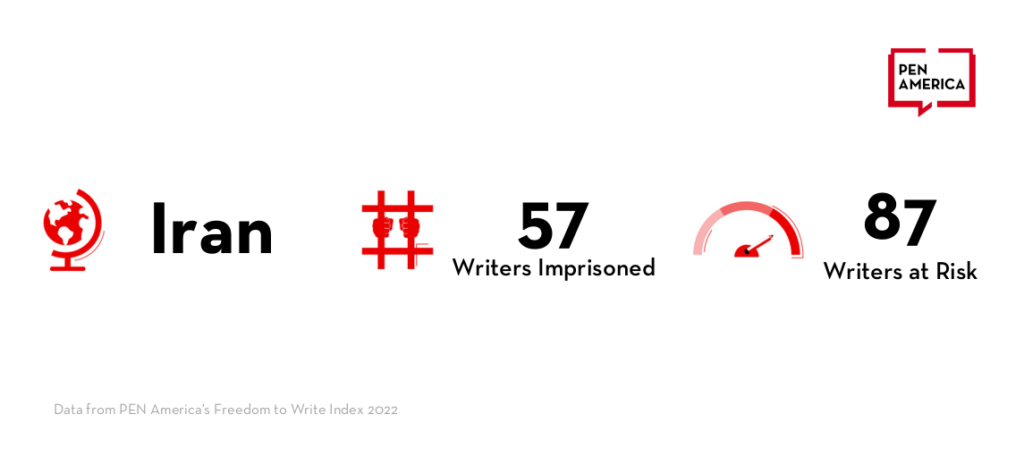

China and Iran: protests are last resort for those whose freedom has been curtailed

China and Iran are among the most inhospitable places in the world for free expression. The two countries jail the most writers, 90 and 57 respectively, but also occupy the top two positions in PEN America’s Writers at Risk Database. Iran showed the largest increase, following ongoing nationwide protests in 2022, with 39 new cases of detention or imprisonment. Iran is also the largest jailer of women writers globally, with 16 of 42 women in custody being in Iran. China is not far behind, with 11 women writers behind bars.

Despite their ever tightening grip on free expression, 2022 saw protests in both Iran and China, as ordinary people found ways to raise their voices in support of free expression and human rights.

“We want food, not PCR tests. We want freedom, not lockdowns. We want respect, not lies. We want reform, not a Cultural Revolution. We want a vote, not a leader. We want to be citizens, not slaves.” These are the words, hand lettered in red, on banners that were hung over a bridge in Beijing, just before the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th national congress in October 2022. Photographs of the banners quickly found their way onto the internet and spread around the world before they were censored in China.

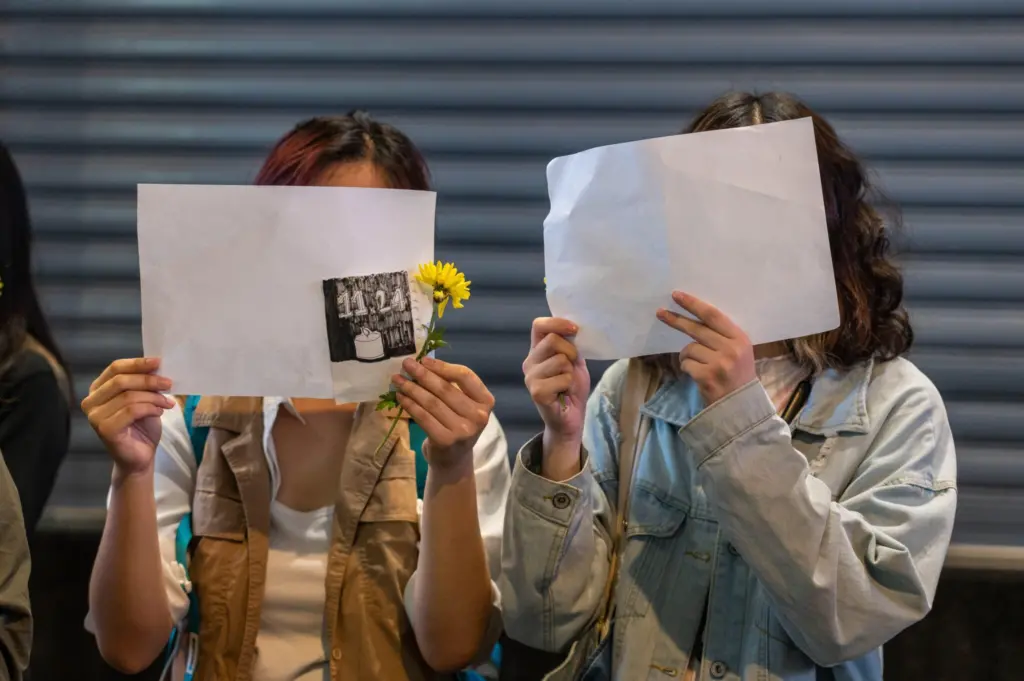

In November and December 2022, thousands of people gathered in dozens of cities across China to protest against the government’s COVID policies. The White Paper protests, as they became known, erupted out after a fire broke out in an apartment building in Urumqi. Media reports about the fire indicated that COVID restrictions hampered residents’ ability to escape and the emergency response. While these protests were initially the culmination of pent up rage about COVID restrictions, including censorship of COVID-related information, protesters also pressed for freedom of expression, action on socio-economic issues and, in some instances, called on Xi Jinping to resign. These protests represent some of the most significant opposition to the Chinese Communist Party since 1989, and featured rare direct criticism of Xi Jinping.

The Chinese government reacted to the protests by dropping the hated COVID measures, but also by arresting key individuals, demonstrating that, while the Party can respond to pressure, openly challenging its authority comes at a cost. In April 2023, writer and human rights lawyer Xu Zhiyong was sentenced to 14 years in prison for writing about democracy in China, a stark reminder that those who inspire others to express themselves are viewed as posing a grave threat to the CCP.

In Iran, nationwide protests were sparked by the September 16 death in custody of Mahsa (Jina) Amini, a 22-year old Kurdish woman who was detained and beaten by the morality police while visiting Tehran with her family, allegedly for not wearing her hijab properly; Amini slipped into a coma after the beating and succumbed to her injuries in hospital three days later. In the demonstrations that continued through year’s end and spread to more than 100 cities, protestors adopted the rallying cry of “Zan, Zendegi, Azadi” or “Woman, Life, Freedom,” a slogan that originated in the Kurdish region, to call for greater human rights and an end to state violence and restrictions against women. By year’s end, more than 14,000 people had been detained and at least 500 confirmed killed in the authorities’ harsh crackdown, which was particularly severe in the ethnic minority Kurdish region as well as the province of Sistan and Baluchestan. Custodial abuse of detainees, including torture and rape, was reported, and two protestors were executed in December, while several dozen more remained at threat of imminent execution.

The crackdown on protests was accompanied by a pre-emptive crackdown on dissent, including among the creative community. Several dozen writers and artists—a number of whom were former political prisoners—were arbitrarily detained in late September and October, including blogger Hossein Ronaghi, writer Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee, poets Atefeh Chaharmahalian, Behrouz Yasemi, and Behnaz Amani, rappers Saman Yasin and Toomaj Salehi, musician and poet Mona Borzouei, and others detailed in this report. Writers, poets, and protestors faced poor conditions in detention, including lack of access to medical care, physical abuse, and due process violations. Meanwhile, authorities attempted to quash the voices of well-known prisoners of conscience, including women’s rights activists Nasrin Sotoudeh and Narges Mohammadi, and of prominent cultural influencers, such as actress and translator Taraneh Alidoosti. The Iranian Writers Association (IWA)—which has steadfastly represented Iran’s writers and taken a stand against state censorship, and been banned since the 1980s—faced additional scrutiny, with a number of IWA members arrested and threatened with legal charges in December. Although early 2023 saw a number of those jailed being released in mass amnesties, the protests, as well as smaller acts of dissent such as women refusing to wear headscarves, continued.

Writers at risk and in custody: the global picture

Prominent columnist and independent media owner Radio M was convicted and sentenced to three years in prison on charges related to “foreign financing of his business.” (Photo by @ElkadiIhsane / Twitter)

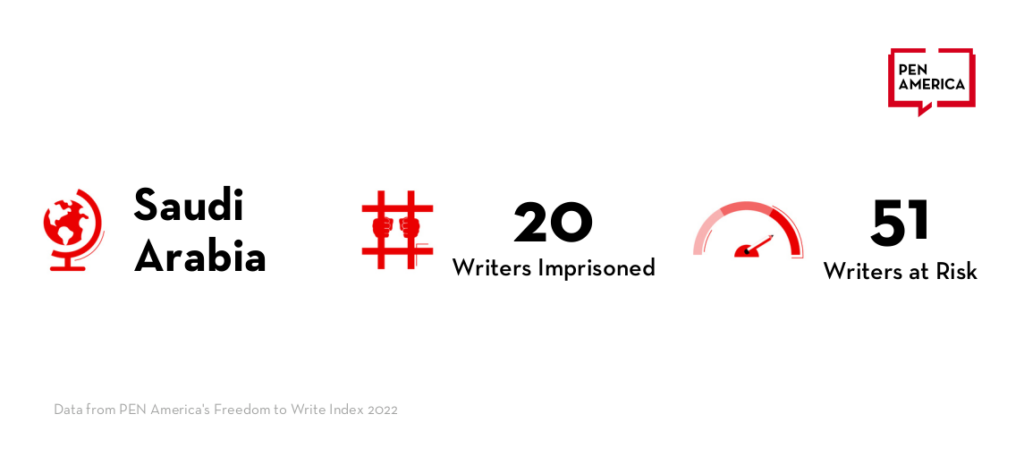

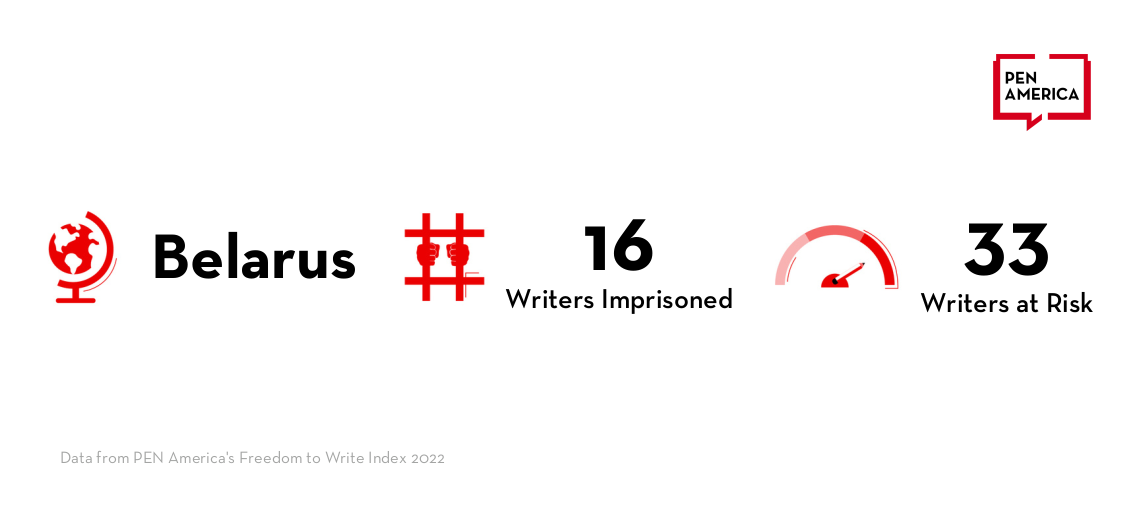

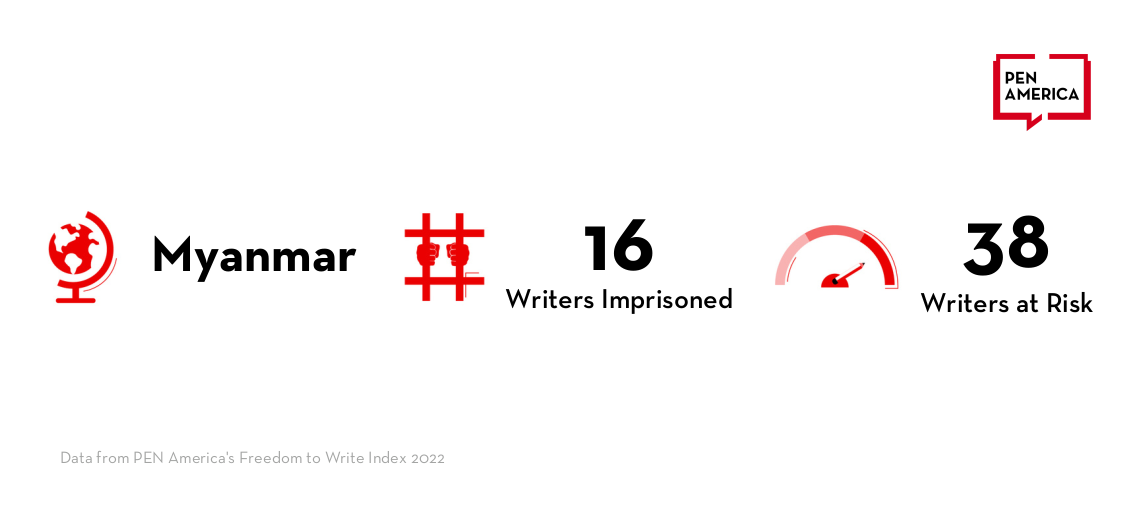

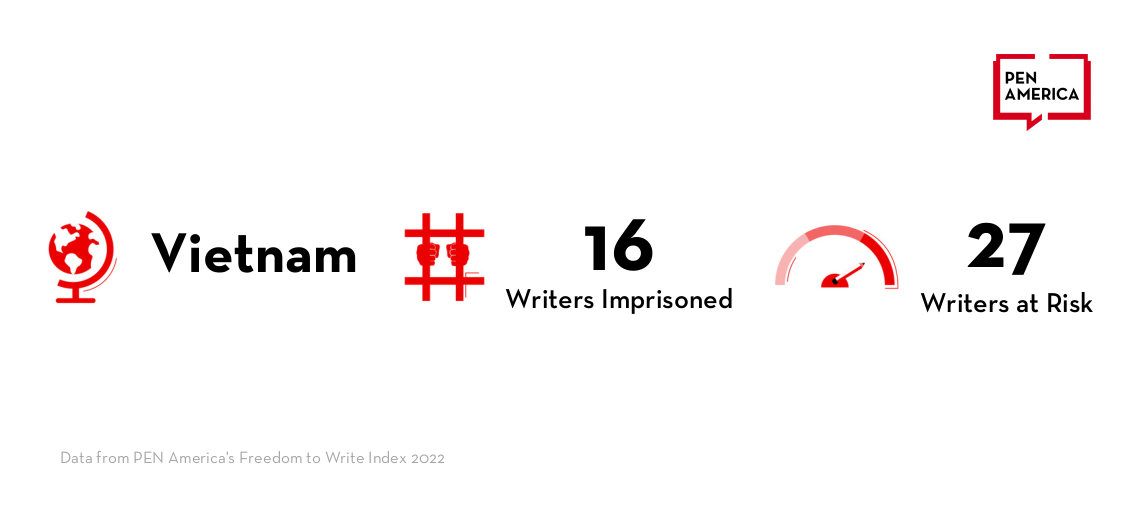

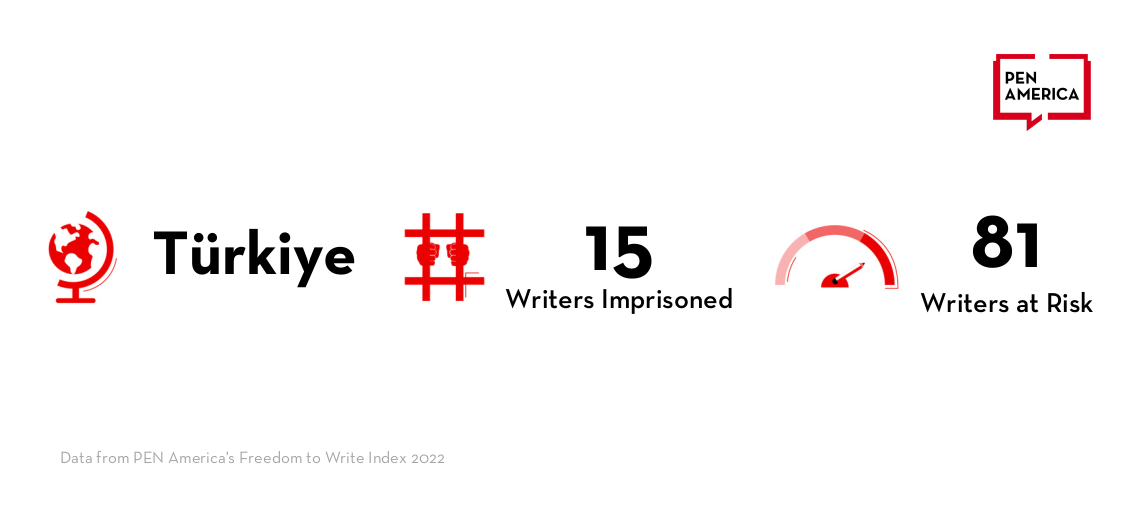

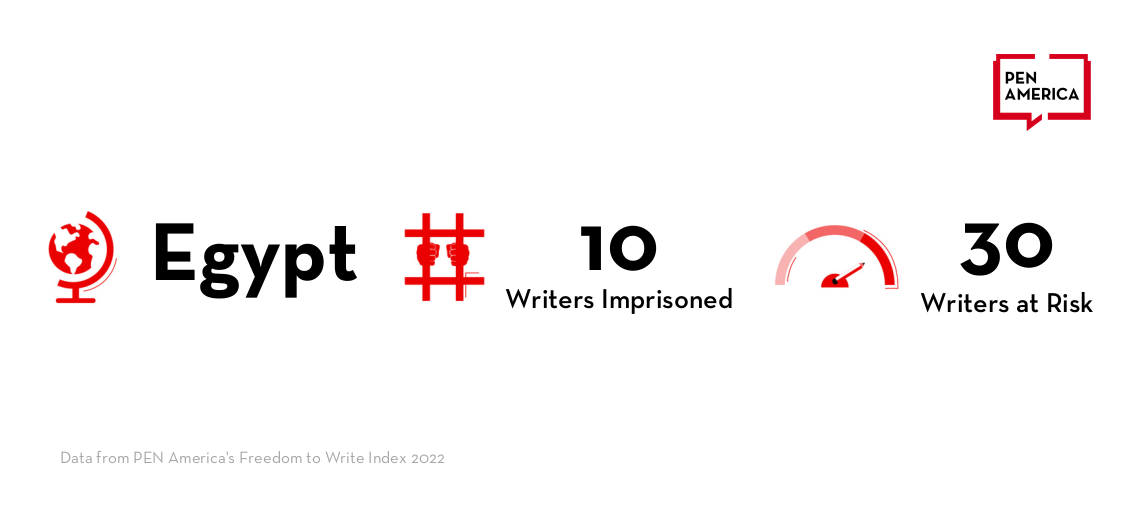

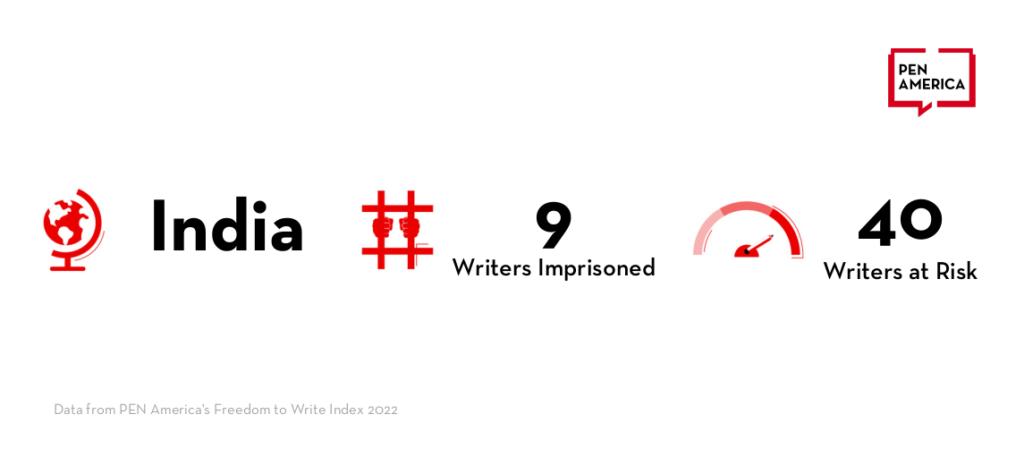

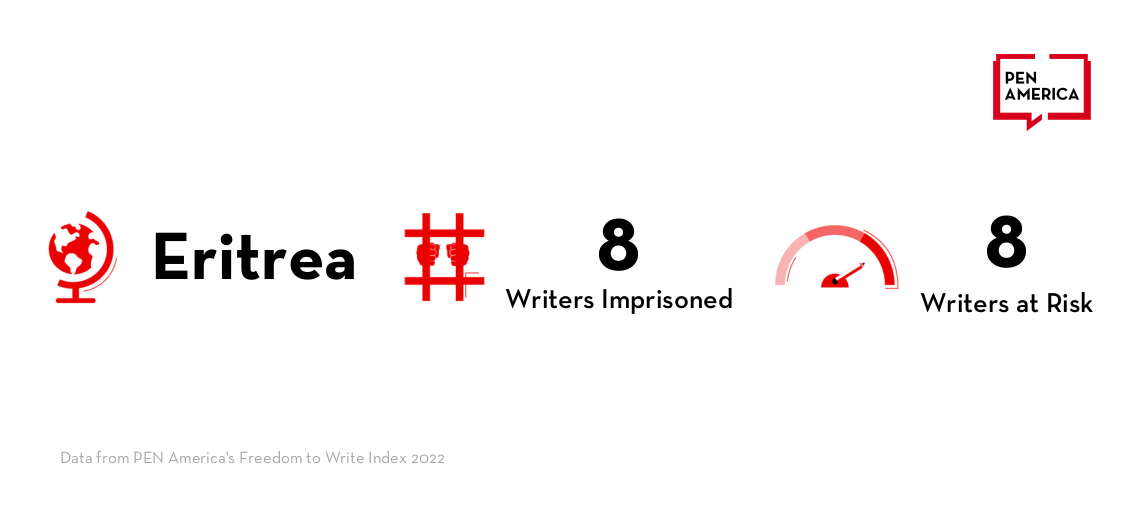

In 2022, the top 10 countries jailing writers remained the same as 2021, although their order shifted as crackdowns against the creative sector accelerated in some countries and eased or assumed different dynamics in others. China remained in first place, while Iran moved into second, largely as a result of the pre-emptive crackdown on the creative sector and the protests. Saudi Arabia dropped into third place with 20 writers jailed, but retained its place in the top three. While some writers were released in Saudi Arabia in 2022, many continued to face unjust limitations on their human rights, including constraints on their freedom of movement and expression. China, Iran, and Saudi Arabia accounted for half of all cases of imprisoned writers and public intellectuals globally, with 54 percent of the total. Belarus, Myanmar, and Vietnam tied for fourth place, each with 16 writers jailed. Türkiye closely followed with 15, continuing the trend seen in 2021, in which the number of writers in jail has decreased, but where other threats such as protracted legal trials, even against writers in exile, continued to chill free expression. Rounding out the top 10, with between eight and 10 writers in jail, were Egypt, India, and Eritrea.

Who are the writers?

Many writers included in the Index and the Database hold multiple professional designations, reflecting that their writing and expression take multiple forms across diverse platforms.

The most prevalent professions of those incarcerated in 2022 were online commentators (132), literary writers (118), opinion/columnist journalists (99), poets (80), activists (72), scholars (65), creative artists (39), singer/songwriters (30), translators (21), publishers (13), editors (11), and dramatists (9).

Notably, individuals tagged as online commentators (a category that includes bloggers as well as those who use social media platforms as a key vehicle for their expression) jumped to the top of the list, reflecting the fact that in many environments that are closed for literary and journalistic writing, online writing remains a meaningful space for those attempting to express dissident views. Additionally, the prosecution of writers for their online expression reflects authoritarian governments’ interest in controlling the narrative on social media platforms and in curbing influential voices of conscience and dissent. The number of poets in custody increased from 68 in 2021 to 80 in 2022, reflecting the large number of poets arrested in Iran, where poetry has traditionally played a significant role in the country’s creative culture and where many poets have taken on sensitive political and social themes in their work as well as pushing back against authoritarianism and religious orthodoxy.

The majority of writers and public intellectuals behind bars during 2022 are men, and men also make up the overwhelming majority of cases in the Database.

Women comprise almost 14 percent of the 2022 Index count, as compared to 12 percent in 2021 (in 2019, the percentage was 16). Countries that have detained the highest number of women writers and public intellectuals track closely with those who have jailed the highest total number of writers. Collectively, authorities in China, Iran, and Saudi Arabia—the top three countries that jailed the most writers during 2022—accounted for 28 of the 42 women writers in the 2022 Index. Iran accounts for 16 of the female writers globally, with a number of female poets, writers, and activists once again put behind bars, joining prominent political prisoners such as Narges Mohammadi and Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee.

There are 813 active cases in PEN America’s Writers at Risk Database from over 80 countries. These cases represent a wide spectrum of threats against writers; taken with the Freedom To Write Index, they present a comprehensive picture of the threats that writers and other members of the writing community face when they criticize those in power. In particular, the Database provides insights into the types of threats that writers face, including in those countries that do not use imprisonment and detention as their primary tactic of repression. The catalog of how those who wield their pens and their words in ways that repressive governments do not like are punished includes forcible disappearance, murder, continual harassment, and exile. In 2022 there were 45 cases of murder in the Database (including past cases where perpetrators have not been brought to account), 16 of forcible disappearance, and 61 cases where individuals were forced to flee from their countries.

Top 10 Countries 2022

There is a significant overlap between countries that detain the largest numbers of writers and those with large numbers of cases in the Database. Cuba is a notable exception: with six writers in custody, Cuba does not make the top 10 list of countries that jail writers, but with 27 cases overall, members of the creative community and journalists are at high risk of various forms of persecution when they exercise their free expression rights to criticize the Cuban government. In June, artists and activists Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and Maykel “Osorbo” Castillo Pérez were sentenced to five and nine years, respectively, punishing them for their artistic expression and leadership in protest movements. Five more writers and artists were detained in October after they participated in peaceful protests in the aftermath of Hurricane Ian.

In the wake of its invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Russian Federation intensified its efforts to quash free expression and dissent inside its own borders, continuing to target independent media and ramping up efforts to contain and suppress anti-war sentiments and protests. The Russian government has explicitly targeted independent media since at least 2015; on March 4, 2022, it criminalized independent reporting on the war and protests against it. In the immediate aftermath of the enactment of these new laws at least 150 independent journalists fled Russia and many others have since followed them into exile. The government also blocked access to various international media websites, among them CNN, BBC World, Deutsche Welle, and France 24.

Russia’s creative community has not been immune from efforts to silence their protests against the war in Ukraine. Alexandra Skochilenko, an artist and musician, was arrested and detained in April 2022 for joining anti-war protests in which people replaced price tags in supermarkets with anti-war messages. She is believed to be the first person arrested in St. Petersburg under the March laws criminalizing “false” information related to the war. Artem Kamardin, Nikolay Dayneko and Egot Shtovba, poets and activists, were arrested for their participation in an anti-war poetry event in September. Kamardin was sexually assaulted during a raid on his home.

Digital repression of free expression

The largest group of writers and intellectuals at risk globally in 2022 is made up of online commentators, a category including bloggers as well as those who use social media platforms as a key vehicle for their expression. As repressive regimes continued to take down traditional forms of media, criminalizing news outlets and controlling broadcasting licenses, the internet remained an accessible means for citizens to share and receive independent ideas and voices.

And as the growing prosecution of writers for their online expression shows, repressive governments are continuing to ramp up their efforts to exploit technology to their political advantage and to control how citizens use these tools. Especially as the pandemic increased the degree to which people work and socialize online, digital repression tools provide unprecedented capacity to monitor personal communications and movement, while being more difficult to track and observe than violent crackdowns and therefore less likely to incite public outcry. In 2022, authoritarian forces around the world normalized a myriad of digital repression mechanisms from censorship to surveillance.

Under the guise of laws protecting against fake news, defamation, and attacks on the social order, writers and artists are being increasingly criminally prosecuted for posts on social media or in messaging apps. The most egregious example involves writer Kyaw Min Yu, known popularly as Ko Jimmy, who was arrested in Myanmar shortly after the military coup for his posts on social media and executed in July 2022 under a counter-terrorism law. We have also seen the criminalization of smaller expressions of dissent online by merely retweeting or liking a post. Salma al-Shehab, a Leeds University Ph.D. student, was arrested while on a visit to Saudi Arabia and sentenced to 34 years for retweeting women’s rights activists. Similarly, Belarus has criminally prosecuted any indication of an anti-war stance online, including pictures of people simply wearing yellow and blue or even just liking a social media comment.

Autocratic governments have increased pressure on technology platforms, as well, requesting rapid removal of specific content or access to personal data of online users. In Vietnam, the government requires that platforms take down “fake news” content within 24 hours, at the same time that dissident voices are harassed and falsely reported by coordinated pro-government digital militias. In China, domestic and foreign companies are pushed to take actions aligned with the CCP if they want to keep operating. Chinese giant social media platform Douyin is reported to have banned live-streams in Cantonese in October, and Microsoft’s web search engine Bing has been found to censor politically sensitive Chinese topics and names, including in regions outside of China. In addition, a Chinese state regulation banning independent publication of “religious information” online came into effect in 2022, allowing only officially vetted publications to publish online on the topics of religious doctrine, knowledge, culture, or activities. This has legalized the practice of selective censorship of minority cultures and religions, such as the Uyghur, Hui, and Mongolian communities – websites and platforms popularly used by these communities had already been shut down previously.

In other attempts to control the digital space, repressive governments are cracking down on tools that provide greater privacy to writers and journalists, such as VPNs and encryption, even prosecuting individuals who advocate for an open internet. In China, Apple has a long documented history of banning encrypted apps from its App Store in China at the behest of the Chinese government, going as far as disabling well known functionalities that allow the exchange of data directly between devices. In Iran, two digital rights defenders were reportedly detained by authorities during the protests. In Saudi Arabia, writer and internet freedom advocate Osama Khalid was sentenced to 32 years in prison, and Ziyad al-Sofiani was sentenced to eight years in prison. They were both high-level volunteer administrators for Wikipedia.

Repressive governments around the world have also relied on more extreme measures such as internet shutdowns to stop the flow of information, especially in moments of political upheaval, protests, conflicts or elections. India was the leader in internet shutdowns with 45% of global recorded shutdowns in 2022. As seen in Iran in the aftermath of the 2022 protests, shutdowns are also evolving to involve more nuanced approaches, for example targeting only mobile networks, or specific regions or social media platforms. India had already banned TikTok and messaging apps such as WeChat in 2020, but in 2022 the trend of governments banning specific social media platforms gained even more traction. The Taliban, for example, banned TikTok and the popular online gaming app PUBG in Afghanistan, ostensibly to prevent youth from “being misled.”

Last year, the 2021 Freedom to Write Index highlighted the threat of digital surveillance as spyware and surveillance tools were exposed as being deployed with increasing sophistication against journalists, writers, and activists, and even their families, friends, and colleagues. In 2022, foreign commercial spyware, including NSO Group’s Pegasus, continued to be used against dozens of activists, journalists, and human rights defenders. NSO Group’s customers include several repressive governments and even democracies – Pegasus has been reportedly sold to 14 member states of the EU and there is official documentation that the Mexican military has spied on citizens and on human rights activists.

As of April 2023, the movement to start curbing the use of commercial spyware has started to gain welcomed momentum after the U.S. President Biden issued an executive order barring federal agencies from using dangerous commercial spyware and another 10 governments committed to tackling its proliferation. While these are welcome developments, there is still significant progress to be made; the executive order doesn’t address the use of surveillance technology developed by government agencies themselves, and governments such as India continue to seek to buy new spyware from lesser known companies.

Top 10 Countries of Concern

China

Overview

In October 2022, China’s leader Xi Jinping began a historic third term as leader of the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The consolidation of political power around Xi signaled that the tightened restrictions on human rights he has ushered in since 2012 would continue. Freedom of expression in China has been systematically suppressed through tight government control over the media, censorship of the internet, and widespread arrests of writers, online commentators, journalists, and human rights activists. Ethnic and religious minorities and those living in ostensibly autonomous areas—including Hong Kong, Inner Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang (the Uyghur region)—continued to face a repressive environment for free expression directed by Beijing under policies of forced cultural assimilation.

China remains the world’s largest jailer of writers with 90 in behind bars in 2022. Writers are often targeted for critical commentary about the Party-State, as well as for their promotion of ethnic minority language and culture. In custody, writers face torture and ill-treatment, including withholding of medical care. Writers also face harassment, intimidation, and mass surveillance, while Chinese writers and dissidents in exile have faced extraterritorial threats.

China remains the world’s largest jailer of writers with 90 in prison in 2022. Writers are often targeted for critical commentary about the Party-State, as well as for their promotion of ethnic minority language and culture.

Writers at Risk: Key Cases and Trends

Despite tight control over the media and internet, Xi Jinping and the CCP faced strong dissent in 2022 as anger at the government’s COVID-19 policies erupted. Despite restrictions on free expression, Chinese people continued to find ways to express themselves, notably in a video circulated online that protested Shanghai’s month–long lockdown in April. In a widely publicized incident, the Chinese authorities censored the video. Throughout the year censors worked to remove social media posts and commentary about the government’s draconian zero–COVID policies, which hid but didn’t erase people’s anger. This discontent reemerged when a lone protester in Beijing, Peng Lifa, stood on a bridge and unfurled banners calling for Xi Jinping’s removal. Widely nicknamed Bridge Man, Peng’s protest slogans spread around the world. In November, sparked by the deaths of Uyghurs in a fire during a COVID–19 lockdown, mass protests broke out across the country. Several participants of these “White Paper” protesters were later rounded up and jailed.

In 2022, authorities continued to use heavy–handed national security charges to punish free expression. In the dominant Han Chinese areas (excluding Inner Mongolia, Tibet, and the Uyghur region), 35 writers were imprisoned. Three writers received prison sentences on charges of “inciting subversion of state power.” In December, activist Ou Biaofeng was sentenced to three years and six months in prison. The court cited his political commentary articles printed in Hong Kong media such as Ming Pao, the now–shuttered Apple Daily, and a Chinese human rights website. In November, poet Wang Zang (real name: Wang Yuwen) and his wife Wang Liqin received prison sentences of four and two–and–a–half years, respectively. The case against Wang centered on his poetry, essays, and performance artworks, as well as interviews Wang gave to foreign media. Wang Liqin was prosecuted primarily for her relationship with her husband, and was released in December. Poet and member of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre Zhang Guiqi (pen name: Lu Yang) received a six year sentence in July for calling on Xi Jinping to step down in a WeChat video.

In June, authorities put Xu Zhiyong, the 2020 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award honoree, on trial for “subversion of state power.” Authorities cited his involvement in a December 2019 meeting and articles and essays as “evidence” of a crime. In April 2023, he was found guilty and sentenced to 14 years in prison. His partner, activist Li Qiaochu, remained in custody throughout the year.

These policies have been part of a broader effort by the Chinese government to forcibly assimilate minorities into the majority Han–Chinese culture and language, suppressing their right to exercise freedom of opinion and belief, individual and cultural expression, and education.

Inner Mongolia

On January 1, 2022, legislation went into effect that formally legalized Beijing’s policies, introduced in 2020, to curtail the use of the Mongolian language. These policies have been part of a broader effort by the Chinese government to forcibly assimilate minorities into the majority Han Chinese culture and language, suppressing their right to exercise freedom of opinion and belief, individual and cultural expression, and education. The measures, which required children to be taught in Mandarin Chinese and removed the use of Mongolian textbooks, sparked protests; the government reportedly shut down a Mongolian–language social media platform that had 400,000 Inner Mongolian users.

Writers and advocates for Mongolian language and cultural expression have faced ongoing pressure after the 2020 protests. Writer Lhamjab Borjigin was sentenced to one year in prison in 2019 and then put under house arrest in late 2020 before eventually escaping to Mongolia. According to written testimony he provided in March 2023 to a human rights group, “Mongolian textbooks and other publications have been removed from bookstores and libraries.” While outside of the jurisdiction of the Chinese authorities but illustrative of Beijing’s influence in suppressing Mongolian cultural advocates, in June 2022 Mongolian authorities sentenced Munkhbayar Chuluundorj, a well–known blogger, poet, and human rights activist, to 10 years in prison. Chuluundorj was sentenced for “collaborating with a foreign intelligence agency” against the People’s Republic of China, which came after he advocated for years for the linguistic and cultural rights of ethnic Mongolians in China.

Tibet

Tibetans continue to be punished for promoting Tibetan culture and the Tibetan language, which Chinese government policies have curtailed. UN human rights experts called such policies “oppressive” and “contrary to international human rights standards” in a November 2022 letter to the government. The Chinese government maintained its information blockade on Tibet; according to reports, no foreign journalist was allowed to enter in 2022. During a COVID–19 outbreak in Lhasa in August, Tibetans turned to social media platforms to express discontent with the lockdown and other government COVID policies. Authorities issued directives for social media companies to increase removal of Tibetan users’ criticism while police launched a campaign to arrest and punish people for their online comments about the pandemic; a total of 786 people were punished with administrative detention or penalties, according to a local police announcement.

Tibetans continue to be punished for promoting Tibetan culture and the Tibetan language, which Chinese government policies have curtailed.

Tibetan writers continued to face heavy prison sentences of between four and 14 years on national security charges in 2022, with at least 12 writers in prison. In September a Chinese court sentenced three writers to prison for “inciting separatism” and “endangering state security.” Poet and essayist Gangkye Drubpa Kyab received the longest sentence of 14 years; writer and environmentalist Sey Nam received six years; and writer and poet Pema Rinchen was sentenced to four years. Another writer, Zangkar Jamyang, disappeared into police custody after being taken away on June 4, 2020. In early 2023, information emerged that he was serving a four–year sentence on charges of “inciting separatism” and “spreading rumors in internet chat groups” for criticizing government policies and writing about the need for Tibetans to preserve their language.

Xinjiang (Uyghur region)

The Chinese government continued its assimilation policies aimed at eradicating Uyghur cultural and linguistic expression in Xinjiang, with devastating effects. A total of 33 Uyghur writers and scholars were imprisoned in 2022. The scale of the CCP’s targeting of Uyghur writers is so vast that the region alone represents the third highest number of cases of imprisoned writers and scholars. In August the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) released a long–delayed report that said the Chinese government’s arbitrary detention of Uyghurs and Turkic Muslim minorities and the deprivation of their fundamental freedoms may constitute crimes against humanity. However, the government continued to evade international accountability for its crimes.

Tibetans continue to be punished for promoting Tibetan culture and the Tibetan language, which Chinese government policies have curtailed.

Uyghur poet Gulnisa Imin is serving a 17.5 year prison sentence on charges of “separatism of state power” for her poetry that preserved and promoted Uyghur language and culture. (Photo by Abduweli Ayup)

Free expression and access to information remained systematically restricted in the Uyghur region. As areas were hit with COVID–19 outbreaks, police issued censorship directives in September 2022 to erase expression by Uyghurs and other residents about the pandemic measures. Restrictions on international media reporting from the region tightened; according to the 2022 report on media freedom authored by the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China, only two foreign journalists were allowed to visit the region in 2022, compared to 32 the previous year.

Writers, scholars, and those who advocate for Uyghur culture or use the Uyghur language faced heavy prison sentences. Due to the information blocking facts emerged in 2022 about some individuals who had been forcibly disappeared years prior. In December, information emerged that Uyghur singer–songwriter Ablajan Awut Ayup was serving an 11-year prison sentence on unknown charges for promoting Uyghur culture and speaking to the BBC in 2017. He initially disappeared in 2018. Uyghur poet and scholar Ablet Abdureshid Berqi was found in August to be serving a 13-year sentence for “separatism” in reprisal for his writing, lectures, and traveling abroad. Police initially detained him in 2017.

In March 2022 a collection of the works of Uyghur scholar Ilham Tohti, the 2014 PEN Freedom to Write honoree, was published in English translation. His family has not heard from him since 2017 and are not sure he is alive. In 2014 Ilham Tohti received a life sentence on trumped-up charges of “separatism.”

Hong Kong

Overview

While the Central Government in Beijing has ultimate authority over Hong Kong, as demonstrated by its imposition of the National Security Law (NSL) in 2020, electoral changes in 2021, and hand picking of the new Chief Executive John Lee in 2022, there is a separate government and legal system in the territory. As such, Hong Kong writers and residents exercising their right to free expression face political and legal challenges that are different from those faced by their counterparts in the mainland. Beijing ushered in the national security crackdown following the 2019-20 pro-democracy protest movement, but the Hong Kong police, prosecutors, and courts undertake enforcement of the NSL and other criminal charges like sedition to punish free expression.

Hong Kong writers and residents exercising their right to free expression face political and legal challenges that are different from those faced by their counterparts in the mainland.

Writers at Risk: Key Cases and Trends

In 2022 nine writers were in custody in Hong Kong as the crackdown on free expression deepened. Authorities in Hong Kong ignored a call from the UN in July to repeal the NSL and the now increasingly applied colonial-era sedition law to target critical expression. Journalists, writers, book publishers, and social media commentators have been arrested for sedition and other crimes.

While Hong Kong was once a territory where freedom of expression flourished, Hongkongers increasingly face prison for exercising this right. Activist and political commentator Chow Hang-tung was convicted in January of “incitement to knowingly take part in an unauthorized assembly,” for a Facebook post and article published in Ming Pao calling for residents to remember the Tiananmen Massacre by lighting a candle; the government banned the annual commemorative vigil in 2020. In April, author and journalist Allan Au Ka-lun was briefly detained on “conspiracy to publish seditious materials” and then released on bail. If charged and convicted he could face up to two years in prison. He used to publish regular commentary in the now-shuttered Stand News, whose staff have been tried on sedition charges, and Ming Pao. In a case heralding a crackdown on publishers for “seditious” books, in September a handpicked national security judge convicted five individuals who published children’s books of “conspiracy to print, publish, distribute, display and/or reproduce seditious publications.” The judge sentenced them to 19 months in prison. Jimmy Lai, the founder of the now-closed Apple Daily newspaper who is already serving a prison sentence on separate charges, remains in custody awaiting trial on NSL and sedition charges tied to the newspaper. He faces a possible life sentence on the NSL charges.

Recommendations

To the United States government:

- Impose Global Magnitsky sanctions on perpetrators of human rights violations against writers in China and Hong Kong;

- Pass legislation to counter transnational repression, of which the Chinese government is the world’s leading perpetrator and which is a threat to free expression globally, including the Transnational Repression Policy Act;

- Ensure writers at risk fleeing human rights abuses in China, including Uyghurs and Hongkongers, have humanitarian pathways to enter the United States and fast-track their asylum claims;

- Expand protective designations for Hong Kong dissidents, including via reintroduction and passage of the Hong Kong People’s Freedom and Choice Act and the Hong Kong Safe Harbor Act, and by continued extension of the Deferred Enforced Departure directive; and

- Passage of the Uyghur Human Rights Protection Act, which would designate Uyghurs and other residents of Xinjiang as prioritized refugees of special humanitarian concern, and/or other legislation and policies which would speed up the processing of asylum cases of the nearly 1,000 Uyghurs who are waiting for their claims to be heard;

- Continue and improve its enforcement of the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA).

To the UN Human Rights Council:

- Pass a resolution to discuss the High Commissioner’s August 2022 report on Xinjiang, which suggested the government of China is committing crimes against humanity against Uyghur and Turkic Muslims, one of the gravest crimes under international law;

- Convene a special session on the situation in China, as called for by dozens independent human rights experts appointed by the Council (Special Procedures);

- Create a Special Procedures mandate to monitor the human rights situation in China.

Iran

Overview

The already restrictive environment for free expression deteriorated sharply during the second part of 2022, as Iran was engulfed in anti-government demonstrations following the custodial death in September of a young Kurdish woman, Mahsa (Jina) Amini, who was arrested for allegedly not wearing her hijab properly. Amidst a broad-based crackdown on protestors during which thousands of people, mostly young men and women, have been arrested and detained and hundreds killed, authorities engaged in a pre-emptive crackdown against Iran’s creative community, systematically targeting known writers, artists, and dissenting voices with arrest and detention, including prominent actress and translator Taraneh Alidoosti, in an effort to chill anti-government sentiments. The UN Human Rights Council established a new fact-finding mission in November 2022 to investigate the deteriorating human rights situation in Iran.

Free expression online—already highly restricted in Iran—came under additional threat. Two weeks before Amini’s death, Iranian authorities passed three articles of the Internet User Protection Bill, restricting access to and use of the internet and placing Iran’s internet infrastructure under the control of the security services. As the protests erupted the Iranian government also curtailed the flow of news, information, and platforms to express dissent by shuttering news outlets, jailing and threatening journalists (including those based abroad), and disrupting or slowing internet access. While Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube were already banned in Iran, access to Instagram and WhatsApp was restricted across all major internet providers on September 21, 2022. Netblocks documented internet disruptions in Zahedan, Sistan, Baluchestan, and Kurdistan Province.

The number of writers and intellectuals in Iran’s prisons swelled, representing a more than twofold increase from 22 to 57. A large proportion of the new cases in 2022 took place after the start of the protests in September, and involved either the pre-emptive detention of known voices of dissent (a number of whom had been previously imprisoned), or the targeting of writers and artists who expressed support for the protestors via their writings or music.

A significant number of female writers jailed globally, 16 of 42, were held in Iran, and this number increased from previous years. While we have previously noted the tendency of Iranian authorities to jail women who write or express critical views regarding the laws and practices that restrict women’s rights, this practice escalated in 2022 in the wake of the women-led protests. This increase reflects the reality that women, including Iran’s creative community of writers and artists, have been at the forefront of the 2022 anti-government protest movement, either actively and/or by writing in support of it.

Writers at Risk: Key Cases and Trends

The Iranian government continued to punish dissent and criticism, often deploying charges based on national security or “propaganda against the state” to crack down on free expression. Several rappers, explicitly targeted because of their criticism of the government, have been charged with offenses that potentially carry the death penalty. A large number of writers and poets, ostensibly targeted because of their writing or expression in support of the protests, faced shorter periods of detention, including the poet and theater director Amirhossein Barimani, literary writer and commentator Farshid Ghorbanpour, and poets Mona Borzouei, Behnaz Amani, Atefeh Chaharmahalian, Behrouz Yasemi, and Saeed Heleichi. Individuals arrested were frequently subjected to violations of due process and human rights, including mistreatment in custody. While some were released without conditions, others have faced charges or have been released on bail, with possible charges hanging over their heads. Their arrest and detention also sends a broader threatening message to the creative community, encouraging self-censorship rather than overt opposition to the government.

Several writers, rappers, and poets, explicitly targeted because of their criticism of the government, have been charged with offenses that potentially carry the death penalty. A large number of writers and poets, ostensibly targeted because of their writing or expression in support of the protests, faced shorter periods of detention.

PEN America’s 2011 Freedom to Write Award honoree Nasrin Sotoudeh was released on a brief medical parole in 2021 that has been repeatedly extended. This dispensation is subject to regular review and Sotoudeh was threatened with being returned to prison in 2022, most often after speaking to or writing for international media outlets. Author, activist, and former political prisoner Narges Mohammadi was given an additional sentence of eight years and 70 lashes in January 2022. She continued to speak out from Evin prison—often as part of a group of female political prisoners who made statements collectively—following the upsurge in demonstrations, demanding basic human rights and protesting against abusive conditions for detainees.

A prominent writer and human rights defender, Narges Mohammadi has been in and out of prison for much of the last decade in retaliation for her support of the rights of women, political prisoners, and ethnic minorities in Iran.

The government’s concerted crackdown on the Iranian Writers’ Association (IWA) continued in 2022. Although writer, IWA leader, and 2021 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Awardee Keyvan Bajan was released in March, his co-honoree and writer Reza Khandan Mahabadi, was kept behind bars (apart from a brief medical furlough in early 2022 after he contracted COVID-19 while in prison) despite pre–existing medical conditions; he remained in prison until his release in a general amnesty in February 2023. Their fellow Freedom to Write honoree, poet and filmmaker Baktash Abtin, died a tragic and preventable death in custody on January 8, 2022, after authorities repeatedly refused to provide him necessary medical care. Labor activists, writers, translators, and IWA members Keyvan Mohtadi and Anisha Asadollahi were detained in May 2022; Asadollahi was released on bail in August while Mohtadi was sentenced to a six-year prison term in January 2023 on specious charges of collusion and propaganda against the state. Late in the year, several current board members of the IWA were detained for around a month before being released on bail in early January 2023, including poets Aida Amidi, Roozbeh Sohani, and Alireza Adineh; their colleague Ali Asadollahi was released in February.

Hossein Ronaghi, a blogger who was detained on September 24, was also subjected to ill-treatment in custody. Ronaghi, who has pre-existing medical conditions and had already lost one of his kidneys from torture during a previous politically-motivated imprisonment, suffered severe beatings and was denied medical care. He was released on bail into hospital in late November, after a 65-day hunger strike. Ronaghi, his family, and his friends received threats and harassment following his release. Literary writer and former political prisoner Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee was arrested on September 26 at her home and assaulted during the arrest by security forces. She was charged with “assembly and collusion, as well as propaganda against the state” for her social media activities. Poet and writer Mehdi Bahman, arrested on October 11, was sentenced to death on charges of espionage, the Revolutionary Court that handed down the sentence cited a television interview Bahman gave to an Israeli TV channel in April; he remained behind bars at year’s end.

The Iranian government also targeted artists and singers/songwriters whose work was critical of ruling authorities and explicitly addressed either political or social themes. Saman Yasin, a Kurdish rapper, was arrested on October 2 in a home raid, tortured during his detention, and charged on October 29 with mohrabeh, or “enmity against God,” a crime that carries the death sentence. This development raised alarm with international bodies such as the UN. Toomaj Salehi, a songwriter and well-known rapper who was first arrested in September 2021 and given a suspended sentence in early 2022, was re-arrested on October 30, 2022 after he published music and social media posts expressing support for the protests. He was held in solitary confinement and severely tortured in custody. He also faces charges that could lead to the death penalty.

Writers advocating for ethnic or religious minority rights continue to be particularly targeted in Iran. In January 2022 Kurdish language teacher and rights advocate Zahra Mohammadi began her prison sentence of five years for “founding or leading an organization that aims to disrupt national security.” Kurdish researcher Mozghan Kavousi, who belongs to the Yarsani religious minority, was detained for four months beginning in September and later sentenced to five years and five months in prison on charges of “assembly and collusion,” “insulting the Supreme Leader of Iran,” and “propaganda against the regime.” Baha’i writer and poet Mahvash Sabet was arrested in July 2022 as part of a crackdown on the minority and sentenced to 10 years in prison in November on the same charges as Zahra Mohammadi. While imprisoned, she spent extended periods in solitary confinement.

Recommendations

To governments and institutions engaging with Iran:

- States maintaining diplomatic relations with Iran should enable facilitation of multiple-entry, non-immigrant visas for members of the creative community to permit temporary refuge from internal risk.

- Enable the fast-tracking of asylum claims for writers and artists who face persecution.

- Work with local authorities to conduct outreach to and support for writers and artists in diaspora communities, who may be targets of transnational repression by the Iranian regime.

- Ensure adequate support to enable civil society groups to assist members of the creative community, including via the creation of fellowships and residencies for threatened and exiled writers and artists.

To the United States government:

- Pass legislation to counter transnational repression, of which the Iranian government is leading perpetrator and which is a threat to free expression globally, including the Transnational Repression Policy Act.

To the UN Human Rights Council, the Independent International Fact-finding Mission on the Islamic Republic of Iran, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Freedom of Expression, and the UN Special Rapporteur in the field of Cultural Rights:

- Regularly speak out on urgent cases of concern, as well as the broader issue of prison conditions and the treatment of political prisoners

- The Independent International Fact-finding Mission should include writers and artists as a special group in their investigations and reports and make efforts to include testimony from these individuals and civil society organizations representing them in a way that protects their identity if needed for their safety.

Saudi Arabia

Overview

The number of imprisoned individuals in PEN America’s Index in Saudi Arabia decreased from 36 to 20 in 2022 as detainees were either released or completed their sentences, but this figure belies the extent to which authorities have closed public avenues for free expression in the country. Of the total number of individuals imprisoned in PEN America’s Index, only songwriter Omar Shiboba was newly detained in 2022, with the other detainees being behind bars before 2022.

The majority of the writers who were behind bars in Saudi Arabia—14 out of 20 in total—had expressed themselves via online commentary on blogs or social media platforms.

The majority of the writers who were behind bars in Saudi Arabia—14 out of 20 in total—had expressed themselves via online commentary on blogs or social media platforms. Arrests and sentences related to free expression in 2022 reflected both the importance of the internet as a medium of communication and Saudi authorities’ increasing control over it. Even as the government projected an outward appearance of cultural openness through the funding and hosting of sports and other cultural events, Saudis faced decades in prison for writing and posting tweets or other social media activity. Additionally, Saudi authorities also used the social media and technology sphere to expand their control over citizens’ private lives; the use of mobile apps to this end is often billed as an effort to expand government services, but in fact it has enabled far-reaching abuses, such as controlling the right of women to travel.

In addition to the Index, Amnesty International reported that at least 15 people were sentenced to prison terms of between 15–45 years in 2022 for exercising free expression. Among the most egregious cases was that of Salma al-Shehab, a Leeds University Ph.D. student who was arrested during a visit to Saudi Arabia; in August 2022 a court sentenced her to 34 years in prison for retweeting women’s rights activists. Around the same time, a court also sentenced Nourah al-Qahtani, a Saudi citizen and mother of five who was not especially politically active, to 45 years in prison for her social media activity and for possession of a book by detained cleric Salman Alaoudah. At least a dozen members of the Huwaitat tribe have been sentenced to between 15–50 years’ imprisonment— with at least three sentenced to death—for protesting their forced eviction to make way for the planned Neom smart city project in northwestern Saudi Arabia, by speaking out on social media and in videos. However, the accelerating trend of digital repression has not stopped international social media and technology companies from accelerating investments in Saudi Arabia.

Meanwhile, U.S. President Joe Biden and other world leaders sought to reestablish or strengthen ties with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the de facto Saudi leader, further undermining the importance of free expression by prioritizing economic and geopolitical concerns. The international community’s rapprochement with the crown prince has also signaled a collective geopolitical decision to move on from the brutal murder of Jamal Khashoggi. In April 2022, a Turkish court ordered an ongoing trial in absentia of 26 suspects in Khashoggi’s murder transferred to Saudi authorities. In November 2022, the Biden Administration argued in a court filing that Mohammed bin Salman had sovereign immunity from a lawsuit filed against him in a U.S. court for Khashoggi’s murder, further stymying any independent path to justice.

Writers at Risk: Key Cases and Trends

Many Saudis behind bars for their writing in 2022 were serving long prison sentences. Essam al-Zamil continued to be imprisoned under a 15-year sentence for his criticism of the Saudi oil company Aramco’s public valuation; his 2017 arrest was an early sign of Mohammed bin Salman’s increasing intolerance toward any criticism of government policies. Abdulrahman Farhana, a Jordanian citizen who wrote about topics including Palestinian issues, was sentenced to 19 years in prison in 2021; he was arrested in 2019 amid a broader wave of arrests of Palestinians, Jordanians, and Saudis active on behalf of the Palestinian cause.

However, some of the imprisoned writers serving the longest sentences are those whose arrests predate bin Salman’s rise to power as crown prince in 2017. Waleed Abu Al-Khair, arrested in 2014, remains behind bars serving a 15-year sentence in relation to his human rights activism, and in October 2022 Saudi authorities prevented him from accessing medication or seeing a doctor while in prison. Fadhel al-Manasef also remained imprisoned in 2022, serving a 14-year prison sentence stemming from his writing and involvement in protests in Saudi Arabia’s Shia Muslim-majority Qatif region in 2011. Many of those in jail for their writing or expression, whether before or after bin Salman’s ascent to power, were charged under the kingdom’s broad counterterrorism or cybercrime laws and are tried in Specialized Criminal Courts, which Saudi authorities created in 2008 to try terrorism suspects but have since routinely used against nonviolent activists, journalists, and writers.

Some writers, such as blogger Raif Badawi and well-known women’s rights activist Loujain al-Hathloul, were conditionally released but face ongoing travel bans, preventing them from traveling abroad and separating them from their families. Al-Hathloul’s conditional release means that she also faces broad limitations on her expression, under the threat of returning to prison. Travel bans and restrictions on freedom of speech and social media use after release from prison are common in Saudi Arabia, either as a direct result of sentencing or as a condition of release. The length of time of these travel bans and their exact justification are often unknown; according to Amnesty International, Saudi authorities often do not give those affected any official information in writing. Conditional release conditions often include a broad ban on former prisoners speaking about their experiences, which also makes information on the exact terms of conditional releases difficult to come by.

While new arrests seemed to slow in 2022, Saudi authorities’ repression of expression took on a more ominous shape and moved beyond arrests of high profile dissidents to broader and more severe restrictions on digital public spaces.

While new arrests seemed to slow in 2022, Saudi authorities’ repression of expression took on a more ominous shape and moved beyond arrests of high profile dissidents to broader and more severe restrictions on digital public spaces. During the first few years of bin Salman’s reign Saudi authorities appeared to detain writers and dissidents in distinct waves, as with the arrests of women’s rights defenders in 2018 and the arrests the following year of bloggers, writers, and academics who supported the women’s rights movement or reform more generally. However, Saudi authorities now appear to be taking aim at the last remaining vestiges of free expression in the kingdom, including social media and open source platforms, handing down sentences that are draconian even by Saudi government standards. A Saudi court sentenced writer and internet freedom advocate Osama Khalid to 32 years in prison, a sharp increase from his initial five-year sentence upon appeal, while Ziyad al-Sofiani was sentenced to eight years in prison. Both Khalid and al-Sofiani were high-level volunteer administrators for Wikipedia, and were reportedly sentenced after Saudi government officials were able to successfully infiltrate the website. The expanding crackdown on online space and compromising of private data is of particular concern as multinational tech companies increasingly invest in cloud computing in the kingdom, and as Saudi state entities in turn increase investments in the social media and tech spheres.

Recommendations

To governments engaging with the Saudi government:

- Use all available avenues to press for an end to impunity in Jamal Khashoggi’s murder.

- Seek to ensure that Saudis living abroad are safe from being targeted by Saudi authorities, including by working with local authorities to conduct outreach to those in diaspora communities who may be targets of transnational repression by the Kingdom;

To the United States government:

- Pass Senate Resolution 109, which would require a State Department report on human rights in Saudi Arabia as a condition of security assistance;

- Pass the Transnational Repression Policy Act; and

- Reintroduce and pass the Protection of Saudi Dissidents Act.

To multinational companies investing in the Kingdom:

- Consider the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and conduct due diligence to identify and mitigate human rights risks related to their activities:

- Carefully consider the implications of the Saudi government’s record on free expression, specifically the practice of jailing social media and open source platform users after infiltrating these services to unmask them, when deciding on whether to invest or launch projects with potentially sensitive data.

- Tech companies and others investing in cloud computing in the Kingdom should avoid compliance with regulations that would result in the sharing of users’ private data with the government.

- Technology companies should refrain from engaging in business practices that enable and/or legitimize the repressive censorious practices of the Saudi government.

- Social media and open source platforms operating in the Kingdom should ensure that the identities of dissidents and anonymous whistleblowers are protected.

Belarus

Overview

The Belarusian government continued and sometimes increased its efforts to suppress free expression in 2022. A report by PEN Belarus on human rights violations against writers, artists and other cultural workers, published in March 2022, documented 1,390 violations of free expression, cultural rights and other human rights abuses in 2022. The report noted that at the end of the year, 108 cultural workers, including writers, poets, musicians and playwrights, were amongst the 1446 political prisoners. The report documented arbitrary arrests and detentions of cultural workers, due process violations and various forms of retaliation, including loss of employment, against those who criticized President Lukashenka and the government. Writers and public intellectuals continued to be jailed for writing about Belarus’s history or publishing Belarusian books and writing critical of President Lukashenka. Belarus has also cracked down on journalists, with 28 journalists and media workers in prison on a range of charges in 2022.

Writers and public intellectuals continued to be jailed for writing about Belarus’s history or publishing Belarusian books and writing critical of President Lukashenka.

In an apparent bid to follow the lead of Russian President Vladimir Putin, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenka deployed legal actions punishing so-called “extremist” materials or groups (a designation often used to suppress access to independent media) alongside other laws to undermine free expression, including leveraging charges of incitement of “social hatred or discord” against political opponents and dissidents. In 2021, news outlet Tut.by was designated “extremist” by a Minsk court and then banned in 2022; more recently, the Belarusian Association of Journalists was designated “extremist” by the KGB. Lukashenka also continued his efforts to control public memory: He issued a decree in January declaring 2022 the Year of Historical Memory in Belarus, focusing on the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic during World War Two. Days later, he signed the law “On the Genocide of the Belarusian People,” declaring that Nazi Germany committed genocide against Belarusians during World War Two and defining Belarusians as “all Soviet citizens who lived on the territory” of Belarus at the time. Historians criticized the law for misrepresenting Nazi killings of Belarusian Jews during the Holocaust as a genocide against all ethnic Belarusians. President Lukashenka’s distortion of history synchronizes with Russian state rhetoric of “denazification” used to justify the war against Ukraine.

Sixteen writers were in custody in Belarus in 2022, including six imprisoned in 2020, following the 2020 presidential election, which was widely regarded as fraudulent.

Writers at Risk: Key Cases and Trends

Many writers jailed or otherwise at risk of persecution following the 2020 election remained in pre-trial detention, began serving prison sentences, or remained in exile during 2022. Writer, human rights defender, and Nobel Peace laureate Ales Bialacki faced new charges on public disorder in September 2022, and was sentenced in 2023 to 10 years in prison on trumped up charges of “smuggling” and “financing actions that grossly violate public order.” Political analyst Valeria Kostyugova, detained since her arrest in June 2021, was sentenced to 10 years in prison in March 2023. Belarusian-Polish author and journalist Andrzej Poczobut was sentenced in 2023 to eight years in prison on the charge of “incitement to racial, national, or religious hatred or discord.” Philosopher Uladzimir Matskevich was sentenced in June 2022 after 10 months of detention, and author-blogger Mikola Dziadok was sentenced in November 2021, after one year of detention; each has been serving a five-year prison sentences. Philosopher Olga Shparaga and author Ruslan Kulevich remain in exile since leaving Belarus in autumn 2020 after persistent threat of detention.

As part of official efforts to control the narrative about Belarus’ history, literary figure Aliaksandr Novikau was sentenced to two years in prison in 2022 for publishing articles that the court ruled were “discrediting the victory in the Great Patriotic War” and had “signs of the rehabilitation of Nazism” and “hostility to groups respecting the history of the Soviet period.”

Violations of cultural rights and free expression often centered on language. While Belarusian is one of the official languages of Belarus, according to the Belarusian Constitution, Belarusian-speakers experience discrimination in various sectors. PEN Belarus documented discrimination based on language in education, media, publishing, and in the provision of goods and services. In May 2022 an independent publisher of Belarusian literature, Andrey Yanushkevich, opened a bookstore in Minsk. The bookstore had been open for only seven hours when it was forcibly shut down after it was targeted by pro-government journalists. GUBOPiK (the Belarusian directorate for combating organized crime) detained Yanushkevich and confiscated 200 books. Yanushkevich was released after nearly a month in detention. In January 2023, after the Ministry of Information filed a suit, the Minsk Economic Court revoked the Yanushkevich Publishing House’s license on the grounds that it was publishing extremist materials. Yanushkevich left Belarus for Poland.

Violations of free expression and culture affected the ability of Belarusians to exercise their other human rights.

Violations of free expression and culture affected the ability of Belarusians to exercise their other human rights. PEN Belarus reported that Belarusian speakers were not able to vote in the February 2022 referendum because there were no ballots printed in Belarusian.

Threats to free expression have effectively limited Belarusian opposition to Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Expressing a pro-Ukraine or anti-war stance, including wearing yellow and blue or even just liking a social media comment, can result in jail time. Four days after Russia’s invasion, Belarusian authorities detained 20-year-old student Danuta Pyarednya for reposting a text that criticized Vladimir Putin and Alexander Lukashenka. Having been accused of “harming the national interests of Belarus” and “insulting the President,” she was sentenced in July 2022 to six-and-half years in a penal colony.

Recommendations

To governments that engage with the Belarusian authorities:

- Fund and support initiatives maintaining Belarusian culture through cultural ministries;

- Ensure adequate support to enable civil society groups to assist members of the creative community, including via the provision of emergency support mechanisms, the creation of fellowships and residencies for threatened and exiled writers and artists, and the expediting of financial and other support for cultural organizations liquidated in Belarus after 2020.

To the UN Human Rights Council and the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights situation in Belarus:

- Categorize cultural figures as a distinct group at risk of human rights abuses in Belarus

- Include violations of cultural rights in the monitoring of and reporting about the human rights situation in Belarus; and

- Establish protection and development programs for cultural figures and organizations.

Myanmar

Overview

The environment for free expression in Myanmar, devastated by the February 2021 coup, remained bleak. The military continued to restrict news and information channels, limit rights of assembly and association, and arrest, detain, and prosecute influential voices in both the political and cultural realms, as well as dozens of journalists. Myanmar’s restrictive laws—including sections of the penal code covering incitement and hate speech, and laws covering online communications—have been used to charge and sentence a broad range of dissenting voices, including writers and public intellectuals, which has chilled expression and the ability to write freely. The digital space—a key platform for writing commentary and sharing creative work, as well as news and information—remained closed and fraught with danger in 2022, with authorities regularly employing targeted internet shutdowns, censorship of websites, and surveillance.

During 2022, the broad-based, countrywide civil disobedience movement (known as the CDM) continued to challenge the military’s illegal takeover and fight for a return to the path toward democracy. Writers, intellectuals, and other creative artists have played a key role in voicing support for the CDM and shadow National Unity Government, which operates from exile, and therefore remain at risk of being targeted for arrest and legal charges. Hundreds of writers, journalists, artists, activists, and public intellectuals, including many prominent or influential individuals, currently either operate from hiding within Myanmar, or have fled into exile in neighboring countries or further afield for their own safety and to avoid almost-certain arrest. In December, the UN Security Council passed a resolution on Myanmar, the first in decades, that noted the scale of the humanitarian and human rights crises facing the country and called on the junta to release the more than 13,000 political prisoners still being held and cease the criminalization of those participating in or supporting the CDM.

Writers at Risk: Key Cases and Trends

The number of jailed writers and artists in Myanmar increased significantly after the coup, as the military preemptively targeted voices of influence for arrest in the immediate aftermath of the coup and detained others in the months that followed. Many of those writers detained (and killed) in 2021 were poets, reflecting the key role that poets have played and continue to play in resisting military rule, a history explored in PEN America’s 2021 report, Stolen Freedoms: Creative Expression, Historic Resistance, and the Myanmar Coup. Myanmar’s position in the Index dropped from third in 2021 to fourth in 2022, while the number of writers behind bars dropped to 16, as more than a dozen of those detained in early-and mid-2021 were released, most in mass amnesties during the year.

In 2022, however, the junta escalated its tactics of repression. Aside from legal charges and lengthy sentences, the military regime executed a group of prisoners in July 2022, including writer Kyaw Min Yu, known popularly as Ko Jimmy, despite pleas from both inside Myanmar and the international community. The executions were carried out in an environment of opacity and mixed signals about whether or not the sentences would be enforced, increasing the pain and uncertainty for their families. The military had initially issued a warrant for his arrest shortly after the coup, due to his critical writings on social media platforms, and he was arrested in October 2021 during a raid on his residence. He was sentenced to death under Myanmar’s counter-terrorism law on January 21, 2022. It was the first time in several decades that the death penalty had been enforced.

Of the group of writers and cultural luminaries detained in the hours just after the coup, all were finally charged and sentenced in 2022 after being held for months in detention without charge, and then later released.

Of the group of writers and cultural luminaries detained in the hours just after the coup, all were finally charged and sentenced in 2022 after being held for months in detention without charge, and then later released. Filmmaker Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi and singer-songwriter Saw Phoe Khwar, both charged with incitement under Section 505(a) of the penal code in December 2021, were released as part of a broad amnesty in November 2022. However, the singer, whose satirical songs have riled the military in the past, was immediately re-arrested and ordered to serve out a separate sentence for ostensibly breaching the Natural Disaster Management Law. Also released in November were writer Maung Thar Cho, who had been sentenced to a two-year prison term with hard labor under Section 505(a) in February 2022, and poet and activist Mya Aye, sentenced to two years in prison under Section 505(c) of the penal code for “inciting hate towards an ethnicity or a community,” a charge related to a 2014 email criticizing ethno-nationalism in Myanmar. Finally, writers Than Myint Aung and Htin Lin Oo, who had been sentenced to three years in prison under Section 505(a) of the penal code for allegedly opposing the coup online and inciting anti-military sentiments, were released in early January 2023 as part of another broad amnesty. Some of those who were released faced continued harassment or restrictions on work or travel, and they continued to face the threat of being re-arrested due to their stature as influential voices.

Most of these individuals were charged with incitement under section 505(a), or under a new vague provision of “spreading false news,” which was added as Section 505(A) of the penal code within several weeks of the coup and has been used to charge a number of writers, public intellectuals, and journalists over the past two years. For example, Maung Yu Py, a well-known poet from Myeik, was detained in March 2021, and sentenced in a makeshift prison court to two years in prison, later reduced to one year, for unlawful assembly and spreading false news. He was released in September 2022.

There were several instances of much longer sentences handed down during 2022 to writers. The Arakanese writer Ko Aung Naing Myint, who writes under the pen name Min Di Par, was arrested on October 15 2021, and sentenced in February 2022 to 10 years under the counter-terrorism law for ostensibly financing local people’s defense forces (PDFs). Wai Moe Naing, a writer and activist also known as Monywa Panda, was attacked and then arrested at a protest in April, and later charged with incitement under Section 505(a) of the penal code, and nine other serious charges, including treason, armed robbery, and murder. In August 2022, he was found guilty of multiple counts of incitement under section 505(A) of the penal code and sentenced to 10 years in prison, and was sentenced to four additional years in prison in October. Similarly heavy penalties were handed down to Frontier columnist and online commentator Sithu Aung Myint, arrested in August 2021, who received multiple sentences on incitement, denigration of the military, and subversion between October and November 2022 totaling at least 12 years in prison.

Recommendations

To governments engaging with the ruling military junta in Myanmar: