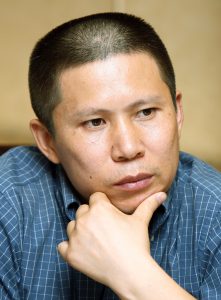

Xu Zhiyong

China

Status: Detained

Xu Zhiyong is a Chinese writer, legal scholar, and civil rights activist who has been an integral member of China’s most important civil rights movements over the last 20 years. Alongside his civil rights advocacy, he is well known for his series of online essays concerning contemporary social issues in China.

Xu was detained on February 15, 2020, after writing multiple open letters and online commentaries criticizing the Chinese government, including its response to the COVID-19 outbreak in the country. Xu has been formally arrested under the charge of “subversion of state power” and faces life in prison if convicted. Xu was previously arrested under an initial charge of “inciting subversion of state power,” after, detaining him incommunicado for nearly a year, authorities escalated the charge to “subversion.”

PEN America Advocacy

June 24, 2022: PEN America, PEN International, the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) publish a joint statement expressing grave concern over the ongoing persecution of Xu Zhiyong following his one-day trial on June 22 and call on the Chinese government to ensure his immediate and unconditional release.

August 2021: The Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission announces that Senator Ed Markey (D-MA) has adopted Xu Zhiyong through the Defending Freedoms Project. Alongside his Advocacy Partner PEN America, Senator Markey serves as Xu’s Advocate and joins the campaign to publicly support his release from detention.

October 22, 2020: PEN America, along with the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights, files a submission before the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention on behalf of Xu Zhiyong. As part of their mandate, United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention reviews individual complaints on behalf of individuals alleged to be arbitrarily detained, raising their case with the host government and making case determinations.

November 2020: Nearly 70 writers and human rights defenders around the world—including J.M. Coetzee, Elif Shafak, Teng Biao, and Helen Zia—join PEN America in calling on President Xi Jinping to release Xu Zhiyong. Sign the letter to join the global literary community in standing with Xu to “defend without question his freedom to write.”

June 4, 2020: PEN America announces that it will award the 2020 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award to detained essayist Xu Zhiyong, recognizing his determined defense of free expression and his fearless critique of President Xi. “We are proud to honor Xu Zhiyong for his indomitable willingness to speak the truth, and to say clearly that his words will not be silenced, his name will not be forgotten, and we will not relent until he is free,” said novelist and PEN America’s president Jennifer Egan.

July 16, 2015: At the two-year anniversary of Xu Zhiyong’s arrest, PEN America publishes an article to advocate for his release.

February 4, 2014: PEN America features Xu Zhiyong in its article “The Human Face of the Free Expression Crackdown in China.”

Case Background

Xu Zhiyong is a writer, legal scholar, and long-standing civil rights activist who has been an integral member of several of China’s most important civil rights movements over the past 20 years. In the early 2000s, Xu was a founding member of Gongmeng (The Open Constitution Initiative), a group of legal scholars and commentators pushing for greater citizens’ rights. Authorities banned Gongmeng in 2009 and briefly detained all those involved.

But Xu persevered, founding the New Citizens’ Movement in 2010. The New Citizens’ Movement is a civil society movement that promotes a citizenry rooted in democratic ideals of freedom, happiness, and societal responsibility. The Movement popularly rallies against government corruption and for greater institutional concern for human rights by the Chinese government, and has faced constant repression by authorities.

Alongside those efforts, Xu has amassed a significant body of work as an essayist, using his writings to advocate for social change. Xu has written prolifically online on issues including access to fair education, governmental mistreatment and repatriation of migrant workers, corruption, and wasteful government spending. Several of his essays stand as major ‘calls to conscience’ that have achieved the status of samizdat-like writing among reform-minded intellectuals, activists, and netizens in China. These include a prominent set of 2012 essays, his manifesto of the New Citizens Movement, an open letter to Prime Minister Xi Jinping entitled “A Citizen’s Thoughts On the Fate of Our Nation,” and an essay on Tibetan self-immolations. Xu is an honorary member of the Independent Chinese PEN Center, granted to him in 2013 on PEN International’s Day of the Imprisoned Writer, November 15.

As a result of his activism, Xu has been on the radar of Chinese authorities for more than a decade. In 2013, Xu was arrested, and in January 2014 he was sentenced to four years in prison (including time already served in pre-trial detention) for “gathering crowds to disrupt public order.” Despite choosing to remain silent to protest his unfair trial, Xu circulated the draft for his court statement “For Freedom, Justice, and Love” online, attracting wide readership. Xu was released in July 2017, after serving his sentence.

In December 2019, amidst a wave of arrests of civil rights activists, Xu went into hiding. During his time in hiding—and as authorities intensified their round-up of activists under the new guise of “coronavirus prevention”—Xu wrote “Dear Chairman Xi, It’s Time for You to Go.” In this open letter, Xu criticized Xi’s leadership, including his handling of the COVID-19 outbreak, and encouraged him to resign.

Xu Zhiyong was detained on February 15, 2020 during a “coronavirus prevention check.” After Xu’s family inquired as to his whereabouts and his status, police told them that he had been placed under “residential surveillance in a designated location” (RSDL) on the charge of “incitement to subvert state power” and denied the family’s request to visit him. Xu has been in incommunicado detention since February 15, having no direct contact with the outside world.

Alongside Xu, his partner Li Qiaochu—a labor and women’s rights activist—was also detained in February 2020 and was held incommunicado by authorities, placed under RSDL. Li’s location, conditions of detention, and even charges against her had been unknown to her lawyer and the public. On June 18, 2020, Li was released on bail.

On March 7, 2020 Xu’s family received notice that he faces charges of “inciting subversion of state power,” a criminal provision commonly wielded against peaceful dissidents, and that carries a maximum penalty of 15 years’ imprisonment. On June 19, 2020, Xu was formally charged. In January 2021, authorities reportedly escalated the charge against Xu, who is now expected to stand trial on “subversion of state power.” The upgraded charge carries a potential sentence of life imprisonment, and it is widely expected that he will not receive a free or fair trial.

Case Updates

June 22, 2022: Xu Zhiyong is tried on the charge of “subversion of state power” in a one-day trial held behind closed doors at Linshu County People’s Court. Xu’s lawyer was required to sign a confidentiality agreement barring him from speaking to the media. Family members and supporters were not allowed to attend the trial.

September 24, 2021: An official indictment shows that prosecutors have accused Xu of conducting illegal activities and plotting a “color revolution” to subvert state power.

March 8, 2021: Li Qiaochu is formally arrested on the charge of inciting subversion of state power.

February 2021: Li Qiaochu is detained by police after accusing the government of torturing Xu Zhiyong in detention on Twitter.

January 2021: Xu is expected to stand trial on the more serious charge of “subversion of state power,” which can carry a sentence of life imprisonment. In comparison, the initial charge of “inciting subversion of state power” carried a maximum of 15 years’ imprisonment.

November 27, 2020: The police question Xu Zhiyong’s girlfriend, Li Qiaochu—who is also an activist in her own right— and take her computer and phone. The authorities threaten detention if she speaks up about his case again.

November 19, 2020: Linyi Public Security Bureau informs Xu’s family that the Shandong Provincial Procuratorate decided to extend the investigation period into Xu’s case to January 19, 2021. This is the third time that authorities have extended the investigation period, which allows police to exempt themselves from Chinese legal obligations to allow Xu access to his lawyer.

June 19, 2020: Police notify Xu’s family that authorities have formally brought charges against Xu, officially arresting him under the charge of “inciting subversion against state power.” The charge against him carries up to 15 years’ imprisonment. Formerly under “residential surveillance in a designated location” (RSDL) pending investigation, authorities reportedly move Xu to Linshu County Detention Center.

March 7, 2020: Xu’s family receives notice that he faces charges of “inciting subversion of state power,” a criminal provision commonly wielded against peaceful dissidents, and that carries a maximum penalty of 15 years imprisonment.

February 15, 2020: Xu is detained by police and placed in incommunicado detention. Police tell Xu’s sister that he is under “residential surveillance in a designated location” (RSDL) on suspicion of “incitement to subvert state power” and deny her request to visit him.

February 4, 2020: Xu’s open letter “Dear Chairman Xi, It’s Time for You to Go” is released to the public online.

December 2019: Amidst a wave of arrests of civil rights activists, Xu goes into hiding.

July 2017: Xu is released from prison upon completion of his four year sentence on the charge of “assembling a crowd to disrupt order in a public place.”

April 11, 2014: The Beijing Municipal High People’s Court denies Xu’s appeal.

January 2014: Xu is tried on charges of “assembling a crowd to disrupt order in a public space.” While he chooses to remain silent to protest the trial, Xu circulates the draft for his court statement “For Freedom, Justice, and Love” online, attracting wide readership. The U.S. Embassy calls for Xu’s release and expresses “deep concern” for his retributive conviction, calling it part of a pattern of arrests of those who challenge the Chinese government. Xu is ultimately sentenced to four years imprisonment, including time served in pre-trial detention.

August 22, 2013: Xu is officially arrested on the charge of “assembling a crowd to disrupt order in a public place,” a vaguely defined charge commonly used against activists.

July 16, 2013: Xu is detained by police under allegations of “assembling a crowd to disrupt order in a public place,” after having spent over 70 days under house arrest.

April 12, 2013: Following an invitation from the Chinese University of Hong Kong and fellow scholar and activist Teng Biao, Xu attempts to travel to Hong Kong to attend an event to commemorate the ten-year anniversary of the Sun Zhigang Incident, involving a migrant worker in Guangdong who died of physical abuse and mistreatment under China’s custody and repatriation (C&R) system. At the border checkpoint, Xu is barred from traveling overseas and is subsequently put under house arrest.

February 26, 2013: Xu distributes leaflets in front of a subway station in Beijing and attempts to organize a protest in support of equal education for people without a Beijing “hukou,” an official registration of household residency which is tied to education and voting rights. He is subsequently summoned by the police, and returns home with “restricted freedom.”

2012: On November 15, Xu writes an open letter to newly elected Prime Minister Xi Jinping entitled “A Citizen’s Thoughts On the Fate of Our Nation,” expressing hope that Prime Minister Xi will guide the country toward substantial social change. Nine days later, Xu is abducted by police and loses contact with the outside world for over 30 hours. In December, Xu publishes “Tibet Is Burning” in The New York Times Chinese language edition to raise awareness about a series of self-immolation protests by Tibetans in China.

2011: Xu runs as a representative in the local-level Haidan District People’s Congress as an independent candidate. His name is removed from the list of candidates, but he nevertheless gathers more than 3,500 votes in his district of 22,000 voters. Xu had previously been twice elected as a local-level representative within the District.

2009: On July 29, Xu is arrested at his home and detained by Chinese authorities on charges of tax evasion. Xu is conditionally released on bail on August 23, but he is prohibited from teaching classes at the Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, where he was a lecturer. The authorities declare the Open Constitution Initiative, a civil society organization co-founded by Xu in the early 2000s, an illegal organization. The government subsequently shuts the Initiative down, and fines the organization 1.46 million renminbi for ‘dodging taxes’ on July 14.

Free Expression in China

In recent years, addressing the dire situation for free expression in China has been one of PEN America’s signature campaigns. With the world’s largest population, and with increased economic and political heft, China’s extensive censorship apparatus limits speech both within and outside its borders. Although new digital platforms have expanded the means of expression, they have also provided more opportunities for repression: in China, even a simple tweet can land its author in jail. Since President Xi Jinping took office in early 2013, he has overseen an extensive crackdown on free speech, implementing additional laws and censorship controls on the Internet, media, and publishers. In addition, individual Chinese writers, journalists, and creative artists have been censored, harassed, imprisoned, and even disappeared for speaking out about sensitive topics such as the rights of ethnic and religious minorities, corruption, and the lack of democratic reform. Read more about freedom of expression in China here.

In Their Words

“In the name of ‘stability maintenance’ the Wuhan Public Security Bureau threatened and denigrated [eight] doctors who tried to reveal the truth about the coronavirus. CCTV in Beijing contributed by actively opposing their legitimate free expression of opinion by broadcasting a damning story about rumor-mongering. The cover-up of the unfolding crisis in Wuhan contributed directly to what is now a national disaster. Stability at any price—at the price of the freedom of the Chinese, their dignity, as well as their pursuit of happiness? For all of that, is the system really all that stable? Because the system is so ill-at-ease and constantly fearful of any and all unexpected developments, it must employ every conceivable means to lash out, crush, and attack…A system that appears to be ultra-stable and is incapable of accommodating change can, when it eventually succumbs, find itself to be beyond treatment and end up digging its own grave.” — Dear Chairman Xi, It’s Time for You to Go

“While on the face of it, this appears to be an issue of the boundary between a citizen’s right to free speech and public order, what this is, in fact, is the issue of whether or not you recognize a citizen’s constitutional rights.

On a still deeper level, this is actually an issue of fears you all carry within: fear of a public trial, fear of a citizen’s freedom to observe a trial, fear of my name appearing online, and fear of the free society nearly upon us.” — For Freedom, Justice and Love — My Closing Statement to the Court, Xu Zhiyong’s closing statement in his 2014 trial on the charge of ‘gathering crowds’

“The New Citizens’ Movement is a political movement. China needs to complete a political transformation, establish a free, democratic China with the rule of law. The New Citizens’ Movement is a social movement. The solution to power monopoly, rampant corruption, wealth disparity, education imbalance, and similar problems does not solely depend on a democratic political system, but also rely on the continuous social reform. The New Citizens’ Movement is a cultural movement. It aims to rid of the tyrannical culture, which is degenerate, depraved, treacherous, and hostile, and build a new nationalist spirit of ‘freedom, justice, and love.’

There must be an end to tyranny, but the New Citizens’ Movement is far from being just a democratic reformation; the New Citizens’ Movement’s discourse is not ‘overthrow,’ but ‘establish.’ It is not one social class taking the place of another social class, but letting righteousness take its place in the Chinese nation. It is not hostility and hate, but universal love. The New Citizens’ Movement pursues facts and justice, but from the aspiration and hard work of not giving up and settling differences. In the process of societal change, there must be new kind of spiritual coalescing of the Chinese people as a whole, from the individual citizen to the entire country.

The New Citizen’s spirit can be summarized as ‘free, righteous, and loving.’” — The New Citizens’ Movement in China