Freedom to Write Index 2021

Key Findings:

Finding 1

Finding 2

Finding 3

This report reflects PEN America’s 2021 Index findings. For our complete, up-to-date database, see the Writers at Risk Database.

Introduction

On February 1, 2021, a military coup violently disrupted Myanmar’s fragile and uncertain experiment with civilian rule. Writers and filmmakers were among those immediately imprisoned. Protesters and poets were soon shot in the streets. As this report goes to press, the world’s eyes are on Russia’s brutal, devastating assault on Ukraine—its people, language and culture, and democracy. Putin’s unbridled aggression, however, is part of a larger resurgence of authoritarianism around the globe.

The past year has repeatedly seen authoritarian forces seek to reclaim powers and territories that had previously passed outside their control; the echoes of the past are heard not only in Europe, but in Myanmar, where the military’s naked attempt to retrieve its lost power brought shock, horror, and then resistance; and in Afghanistan, where the Taliban’s swift recapture of the country following U.S. military withdrawal seemed to—almost overnight—decimate the progress Afghans had painstakingly made over the last 20 years and are struggling to uphold, including with regard to women’s rights, freedom of expression, cultural and artistic creativity, and the development of independent media. From Tunisia to Sudan to Nicaragua, old forces re-exerted themselves and moved to quash democratic progress. And in Hong Kong, a city with a robust history of vibrant freedoms, the reach of the Chinese government has been extended, most formally in the application of the National Security Law against writers and independent media. This has not only led to a crackdown, but also created a climate of looming fear and a sense that safety may only lie in silence, or exile. In Russia, a concerted effort to eliminate what remained of independent media and the space for dissent over recent years laid the groundwork for Putin to maintain total information control in wartime.

In democracies as well, authoritarian tactics are being employed. Censorship and intimidation of dissenting voices is rife in India. In the United States, efforts to ban books and enact laws that would bar discussion of certain topics in classrooms spiked in 2021. Much of this debate centered around the freedom to contend with and openly debate the complexities of history. This, too, has echoes around the globe. Just before Russian troops began this latest incursion into Ukraine, Putin gave a speech in which he attempted to rewrite Ukraine’s history to suit his own ends. For years now, Putin has held in prison the historian Yury Dmitriev on specious charges of child pornography; Dmitriev’s true crime was uncovering and documenting mass graves from the Stalinist era, a historical truth that contradicted Putin’s attempts to whitewash and glorify the memory of Stalin. Government attempts to silence those who study, document, and debate history are typically also an attempt to exert a sole narrative over the past, one that serves the interests of the present.

Yet in all of these cases, authoritarian regimes have been met with resistance. In Myanmar, widespread and sustained civil disobedience—including the creative resistance of writers and artists—followed the coup. Afghan women refused to be silenced and they, too, have taken to the streets. Belarusians have continued their resistance against a president holding onto power despite an election he seemed to think he could steal without a fight. And today, Putin must contend not only with the fierce resistance of the Ukrainian people, but also Russians inside the country and around the world who persist in speaking the truth.

As truth-tellers, creative visionaries, and documentarians, writers have been at the forefront of these movements to resist authoritarianism, and they have been targeted as a result. The Iranian Writers’ Association has become a prime target of its government for its persistence in celebrating literature, condemning censorship, and commemorating past attempts to silence Iranian writers. PEN America’s sister organization PEN Belarus, despite being formally dissolved by a Belarusian court in August 2021, perseveres in documenting its government’s assaults on writers, artists, and all those who insist on their right to speak freely.1PEN America, “Court Formally Dissolves PEN Belarus,” press release, August 9, 2021, pen.org/press-release/court-formally-dissolves-pen-belarus/ Myanmar’s creative community has braved brutal violence and used their writing and artwork to resist the coup and represent the public’s demands for freedom.2“Stolen Freedoms: Creative Expression, Historic Resistance, and the Myanmar Coup,” PEN America, December 16, 2021, pen.org/report/stolen-freedoms-creative-expression-historic-resistance-and-the-myanmar-coup/ Cuban artists and writers have persisted, despite repeated arrests, in critiquing their government and calling for change.

In these countries and others, and as PEN America’s Freedom to Write Index documents, writers and public intellectuals have been unjustly locked up for their exercise of free expression; dozens are currently serving sentences of 10 years or more for their words. In countries notorious for poor prison conditions, the mistreatment of political prisoners through solitary confinement or torture has been compounded by the grave threats to their health posed by COVID-19 and its spread inside jails. But governments’ attempts to muzzle dissent have failed to extinguish individual writers’ voices. In the face of repression, literary communities have come together in defense of writers under threat; writers in prison have gone on hunger strikes—not to call for their own release, but on behalf of others unjustly jailed. Translators have made threatened writers’ words available to a global audience. And across the world, advocates and allies have read aloud the words of those whose governments would see them silenced, and shared the work of those whose governments would see it destroyed. And that work has offered hope to all who seek to push back against the forces of repression.

In the face of an authoritarian resurgence, writers are at the forefront of the defense of free expression and also have an essential role to play, pushing back against attempts to control the narrative; sustaining cultures and languages under threat; holding governments to account—on issues as varied as corruption, their response to COVID-19, or upholding basic rights; and envisioning new possibilities for the future. The freedom to write guarantees our collective ability to imagine and to inspire, and it demands our defense.

During 2021, at least 277 writers, academics, and public intellectuals in 36 countries—in all geographic regions around the world—were unjustly held in detention or imprisoned in connection with their writing, their work, or related advocacy.

The Global Picture

During 2021, according to data collected for the Freedom to Write Index, at least 277 writers, academics, and public intellectuals in 36 countries—in all geographic regions around the world—were unjustly held in detention or imprisoned in connection with their writing, their work, or related advocacy. This number is slightly higher than the 273 individuals counted in the 2020 Freedom to Write Index, and significantly higher than the total in 2019 (238). By far the most significant increase was seen in Myanmar, as a result of the crackdown that followed the military coup there on February 1, 2021, which has included the deliberate targeting of writers and the broader creative community. The numbers of those detained in Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Belarus dropped from 2020, although many of those released from prison in Saudi Arabia continue to face draconian, unjust conditions on their release, including constraints on their freedom of movement and expression. In Belarus, the sharp uptick in detentions—many of them short-term—that accompanied the protests after the stolen election of August 2020 dropped off, though 2021 increasingly saw targeted arrests of writers and others who continued to speak out, and longer-term detentions.

Writers Imprisoned Globally: 2021

A worsening and in some cases violent closure of civil society in many countries led to a reshuffling of the world’s top jailers of writers and public intellectuals. Two countries, however, remained stable in their notoriously high rankings: China and Saudi Arabia remained the first and second-worst jailers of writers, with 85 and 29 writers detained, respectively. Myanmar escalated to the third-worst jailer of writers and public intellectuals, with 20 individuals newly detained in 2021 and 26 total behind bars; Myanmar was jointly ranked ninth last year with 8 detentions. These three countries alone accounted for half of all cases, just over 50 percent of the total. Myanmar catapulted into third place due to a widespread crackdown on civil society and free expression in the wake of the February 2021 coup, in which the military seized power and prevented the elected parliament from forming a new government. Many writers, creative artists, and influential cultural figures were targeted during the first hours of the coup; over the course of 2021, at least 26 detentions of writers and intellectuals were documented.

In Iran, a significant uptick was also documented: at least 21 writers were in prison or detention during the year, remaining the fourth-worst jailer of writers around the world as documented in 2020. While some writers counted in Iran in the 2020 Index have been released, at least 8 writers were newly jailed during 2021. Rounding out the top five with 18 writers held in detention—compared to 25 last year—is Turkey, where a decline was documented due to the welcome release of writers; some had been detained for more than four years. Other prevalent threats against writers in Turkey such as physical attacks and protracted legal trials, even against writers in exile, were documented throughout 2021, though not captured in this figure.

As has been documented previously in the Freedom to Write Index, the overwhelming majority of writers and public intellectuals held behind bars during 2021 are men. This disparity has widened: women comprise 12 percent of the 2021 Index count, as compared to 16 percent in 2019. Countries that have detained the highest number of women writers and public intellectuals track closely with those who have jailed the highest total number of writers. Collectively, authorities in China, Myanmar, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Turkey—the top five countries that jailed the most writers during 2021—accounted for 27 of the 33 women writers in the 2021 Index. The remaining six women writers were jailed in Egypt, Belarus, India, and Vietnam, all countries ranking in the top 10 worst jailers of writers.

While many writers included in the Index hold multiple professional designations and are, for example, both literary writers and poets, the most prevalent professions of those incarcerated in 2021 were literary writers (111), scholars (59), poets (68), singer/songwriters (27), publishers (12), editors (9), translators (8), and dramatists (4). Notably, the number of poets jailed during 2021 increased compared to the 57 jailed during 2020, likely reflecting the bold stance many poets have taken on sensitive political and social themes, as well as the key role they have played in pushing back against authoritarianism in countries like Myanmar. Of the 277 individuals counted in this year’s Index, 4 died while in custody and 197—nearly three-quarters—remain in state custody at the time of this report’s publication. By holding these individuals behind bars, their governments are depriving them of their individual right to free speech, while also robbing the broader public of access to their innovative and influential voices of dissent, criticism, creativity, and conscience.

The majority of the writers and intellectuals included in the 2021 count were initially imprisoned or detained prior to 2021, or had faced previous detention or imprisonment. Of the 277 in prison or detention during 2021, roughly 72 percent had also spent multiple days behind bars in 2020. A smaller but significant subset of these writers, roughly 53 percent, were counted in the 2019 and 2020 Indexes as well. In addition to long-term imprisonments, this percentage includes cases of writers who have been repeatedly detained and released over the course of the past three years, indicating the continued pressure and repression many writers face. This year’s count of 277 also includes 15 cases of individuals who were detained or imprisoned prior to 2021 but whose status, or further information about their case and writing only became publicly known during the past year. Such cases are common, especially in environments where there is little transparency to the judicial process, extensive surveillance and self-censorship, and extremely limited access to information or media freedom; for example, China, including Tibet and Xinjiang, accounts for 7 of these 15 cases. In many such cases, detention is not confirmed until formal charges are brought. The 2021 Index includes 60 writers and intellectuals, in 20 different countries and territories, who were newly detained or imprisoned in 2021—a decline in new detentions and imprisonments in comparison to 2020.

Regarding the types of legal charges brought against jailed writers, many of the trends documented in the 2019 and 2020 Freedom to Write Indexes persisted in 2021. Threat to national security remains the primary category of legal charges that authorities around the world use to justify jailing writers and public intellectuals: at least 55 percent of detentions are based on allegations that writers have undermined national security. Examples of these charges include “membership in a banned group,” which are in some cases levied against writers for belonging to writers’ associations or cultural organizations; and “conspiracy to seize” or “subversion of” state power, often levied against writers who analyze politics, participate in public discourse, or write critically about government affairs. Other less widespread but frequent charges wielded against writers and public intellectuals include illegal assembly and organizing; retaliatory criminal charges such as tax crimes, fraud, and “resistance”; and criminal insult or defamation laws.

Situations in which charges are undisclosed or have yet to be brought against a writer—otherwise known as arbitrary detentions—made up at least 22 percent of the cases in this year’s Index. Arbitrary detentions represent a total lack of due process and deny writers and public intellectuals any recourse to challenge the claims against them; in some cases, they can last for decades. All eight of the cases counted in Eritrea are considered arbitrary, as few details have been disclosed in these cases, and the writers have been held incommunicado, several of them since 2001. Cases of arbitrary detention are also particularly common in Saudi Arabia, where at least 66 percent of the writers and public intellectuals jailed in 2021 were held for no stated reason. This staggering fraction is identical to the percentage documented in 2020, indicating that the prevalence of arbitrary detention has seen no change over the past year. Roughly 53 percent of the writers and public intellectuals in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China have been detained or imprisoned without legal justification. In contrast, China—when excluding autonomous and special administrative regions—has only one case of arbitrary detention: poet Cui Haoxin, also known as An Ran.

Several places where free expression was severely under threat in 2021 nonetheless do not make a significant appearance in the Index. The return to power of the Taliban in Afghanistan has had a devastating impact on freedom of expression and placed writers, artists, and public intellectuals—especially women and members of ethnic and religious minority groups—in grave danger, yet few detentions have been recorded in the initial months following their takeover. The introduction of the oppressive National Security Law in Hong Kong in 2020 has seemingly only led to a handful of new cases of writers behind bars, and despite the further crackdown on free expression in Russia, it does not appear among the countries most responsible for detaining writers and intellectuals. This illustrates that while these numbers are an important indicator of the gravity of threats writers and intellectuals face for exercising their freedom of expression, they tell only part of the story of how free expression may be chilled.

While the COVID-19 pandemic has not, by and large, led to the more dramatic society-wide crackdowns on free expression that initially seemed possible, it has nonetheless had an insidious effect on writers and public intellectuals around the world, with the introduction of new “fake news” laws targeting dissent, new and subtle forms of surveillance, reduced opportunities for global connection and income, and the erosion of support systems that individuals under threat rely on to continue their work. It has also continued to vastly increase the health risks for writers behind bars. As the difference in the pandemic’s trajectory across countries becomes more stark, it is essential for advocates to keep top of mind the impact it continues to have on writers under threat, and especially those from already vulnerable communities.

Regional Breakdown

Governments in the Asia-Pacific region continued to jail the most writers and intellectuals for their writing or expression, with their share of the global total increasing in 2021, largely due to the crackdown in Myanmar. In total, 137—or nearly half of the global count—were jailed in countries in the Asia-Pacific, with the vast majority of those, 85, held in China. Following the February 2021 coup, Myanmar catapulted up to second in the region, with 26 held, while significant numbers continued to be jailed in Vietnam (10) and India (8). Countries in the Middle East and North Africa have also jailed significant numbers of writers and intellectuals, most notably Saudi Arabia (29), Iran (21), and Egypt (14). Countries in this region made up nearly 30 percent of the global count of imprisoned and detained writers, at least 82 individuals, in 2021.

Detentions and imprisonments of writers and intellectuals in Europe and Central Asia—accounting for 14 percent of the global total—occurred largely in two countries: Turkey and Belarus. Turkey moved to the fifth-place position, having held 18 of the 39 prisoners and detainees in Europe and Central Asia during 2021. The ongoing crackdown against those who have vocally opposed Belarus’s stolen 2020 presidential election continued to result in arrests and detentions in 2021, placing Belarus in seventh place worldwide, with 10 writers counted in the Index. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa contributed to roughly 4 percent of the 2021 Index, with 11 writers and public intellectuals detained or imprisoned. The vast majority of those were in Eritrea, which placed 10th with 8 writers behind bars. In the Americas, only Nicaragua and Cuba are represented, making up 3 percent of the 2021 Index total. Detentions of writers and public intellectuals in Cuba account for 7 of the 8 writers detained or imprisoned.

Top 10 Countries of Concern

China continued to top the list of countries detaining writers and intellectuals, with 85 detained or imprisoned in 2021, far more than any other country. Following China, the other top jailers of writers and intellectuals were Saudi Arabia, Myanmar, and Iran, each of which engaged in a concentrated targeting of dissenting voices in 2021 and held 20 or more writers behind bars. Saudi Arabia’s overall numbers decreased slightly from 2020 due to significant numbers of political prisoners being conditionally released during 2021, as did overall numbers in Turkey, where a handful of writers were additionally released upon completion of their years-long sentences. There was a considerable jump in detentions in Myanmar in the wake of the February 2021 coup, after which writers and creative artists were targeted for arrest alongside politicians and other influential figures. A smaller increase was apparent in Iran due to an ongoing crackdown against dissenting voices in which a number of writers were newly detained or summoned to serve previously imposed sentences in 2021.

China

During 2021, China remained stable in its position as the top jailer of writers and public intellectuals in the world. The total number of writers and public intellectuals in China, which includes the Xinjiang and Tibetan Autonomous Regions and Hong Kong, increased slightly from 81 to 85. The vast majority of these 85 writers have been in prison for at least several years, with 53 of them having been counted in both the 2019 and 2020 Freedom to Write Index reports as well. The myriad reasons that the authorities jail writers in China vary; writers whose words question prevailing public opinions or challenge the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) narratives are especially at risk of detention and imprisonment. And the Chinese government’s response to writers and public intellectuals exercising their universal rights to free expression is swift and wide-ranging.

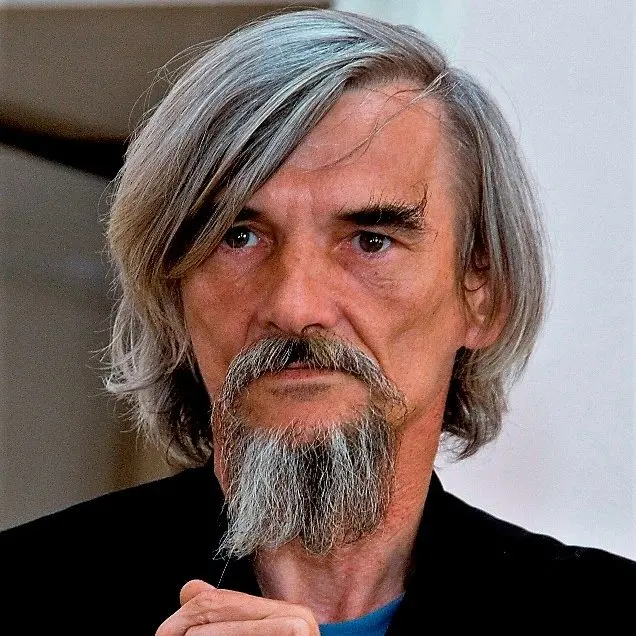

Xu Zhiyong was arrested after publishing critical online commentaries of Chinese government policies and President Xi Jinping. (Photo by AP/Greg Baker)

Within China (excluding Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Inner Mongolia3The Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region has been included in previous publications of the Freedom to Write Index, but PEN America did not identify cases of detained or imprisoned writers or public intellectuals in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region during 2021 according to our methodology.), PEN America places the number of imprisoned writers or public intellectuals at 38. This number includes many writers and dissidents who have criticized government policy or the CCP’s leadership. The initial rationales for detaining these writers are often unstated or unclear, demonstrating the outsized scope of writing, speech, and other forms of expression that can be potentially considered “criminal.” Detained dissident writer Guo Quan’s trial for criticizing the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic online began in September 2021. According to Guo’s lawyer, the prosecution cited almost 20 articles Guo wrote in its case against him for “inciting subversion of state power.” His articles criticized the CCP’s response to the pandemic, but his writings about social injustice and government corruption were also cited as evidence.4Debi Edward, “The missing number behind China’s coronavirus crisis,” ITV News, February 21, 2020, itv.com/news/2020-02-21/the-missing-number-behind-china-s-coronavirus-crisis; Xue Xiaoshan, “Veteran Chinese Democracy Activist Stands Trial For ‘Subversion’ Over Articles,” Radio Free Asia, September 10, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/china/trial-09102021103820.html In 2020, Xu Zhiyong, an essayist, legal scholar, and critic of President Xi’s policies, was initially detained on the same charge; but during January 2021, authorities escalated the charges from “inciting subversion” to “subversion,” increasing his potential sentence to life in prison.5PEN America, “Reports: China to Escalate Charges Against PEN America Honoree Xu Zhiyong,” press release, January 22, 2021, pen.org/press-release/reports-china-to-escalate-charges-against-pen-america-honoree-xu-zhiyong/ Artist, activist, and online writer Chen Yunfei was detained on March 25, 2021, on the charge of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” after he published his thoughts on China’s nine-year compulsory education law based on his visits to schools in the Sichuan province. In contrast with President Xi’s declared emphasis on “rule of law,” the law against “picking quarrels” has been used by authorities as a catch-all criminal provision that is unclear, broad, and confusingly applied.6Guo Rui, ‘Picking quarrels and provoking trouble’: how China’s catch-all crime muzzles dissent,” South China Morning Post, August 25, 2021, scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3146188/picking-quarrels-and-provoking-trouble-how-chinas-catch-all In December 2021, Chen was ultimately convicted of a different crime—he was sentenced to four years in prison for a retaliatory charge of “child molestation.” Chen vehemently rejects the charge as intended to discredit his work and slander his reputation.7Sun Chen, “Court in China’s Chengdu jails veteran rights activist on ‘trumped-up charge’,” Radio Free Asia, December 6, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/china/charge-12062021141519.html

In some cases, a writer’s mere public stature and past history as a person critical of the government is reason enough for Chinese authorities to jail them. In May 2021, writer and former Guizhou University economics professor Yang Shaozheng went missing. Though no reason has yet been disclosed for his arrest, Yang had been dismissed from Guizhou University in 2018 for writing two articles that questioned the CCP; specifically, the monetary costs of the party’s millions of official personnel.8Editorial Board, “Opinion: A professor dared tell the truth in China—and was fired,” The Washington Post, August 23, 2018, washingtonpost.com/opinions/a-professor-dared-tell-the-truth-in-china–and-was-fired/2018/08/23/9fd81eee-a653-11e8-a656-943eefab5daf_story.html In June 2021, Yang was charged with “inciting subversion of state power” and placed under residential surveillance in a designated location (RSDL),9“Locked Up: Inside China’s Secret RSDL Jails,” Safeguard Defenders, October 5, 2021, safeguarddefenders.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Locked%20Up%20%28High%20Res%20version%29.pdf a form of extrajudicial detention. At the end of 2021, he was formally arrested and reported to be held at a detention facility in Guiyang City.10“前贵州大学教授杨绍政被正式批捕 (Yang Shaozheng, former professor of Guizhou University and critic of government policies, is formally arrested),” Radio Free Asia, November 11, 2021, rfa.org/mandarin/Xinwen/6-11112021115902.html Outspoken poet Zhang Guiqi, also known as Lu Yang, was arrested on the same charge for undisclosed reasons. He was detained throughout 2021 in Shandong, after a secret trial in September 2020 in which no sentence was announced.11“256. Zhang Guiqi,” Independent Chinese PEN Center, accessed February 24, 2022, chinesepen.org/english/256-zhang-guiqi Experts suspect his detention is related to a video in which he called on President Xi to resign, but reiterate that the lack of legal transparency makes the exact reason difficult to discern.12“Police in China’s Shandong Detain Outspoken Poet For ‘Subversion’,” Radio Free Asia, May 14, 2020, rfa.org/english/news/china/poet-detained-05142020134933.html Hui Muslim poet Cui Haoxin, also known by his pen name An Ran, was arbitrarily detained in early January 2020 and has not been heard from since. Cui used online platforms and poetry to write about and protest the Chinese government’s mistreatment of Muslim minorities, including the mass detentions of Uyghurs in Xinjiang.13“China Detains Hui Muslim Poet Who Spoke Out Against Xinjiang Camps,” Radio Free Asia, January 27, 2020, rfa.org/english/news/china/poet-01272020163336.html; Associated Press, “Chinese Muslim poet Cui Haoxin fears his people will suffer as history repeats itself in wave of religious repression,” South China Morning Post, December 28, 2018, scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/2179831/chinese-muslim-poet-fears-his-people-will-suffer-history-repeats Employing arbitrary detention and vague charges—many of which international jurists have decried as in contravention with rights to free expression and due process—Chinese authorities continue to demonstrate their sweeping ability to jail writers and public intellectuals.

妻子的遭际令我痛彻心肺,每延迟一天于我都是精神酷刑。诸位公仆亦为人夫,想必亦有常人共情同理之心,应该能够想象和体谅我的这份锥心之痛。

My wife’s experience brought deep sorrow upon me, and every delay of a day is a mental torture. Your public servants are also husbands, and you must have empathy with ordinary people. You should be able to imagine and understand my heart-wrenching pain.

After being detained even once, writers can face intensified surveillance and restrictions on their travel and must essentially continue to live with targets on their backs, under constant threat of being captured again. Writer and democracy activist Yang Maodong, also known by his pen name Guo Feixiong, was detained at Pudong International Airport in Shanghai in late January 2021, when he tried to visit his ailing wife in the United States.14Chris Buckley, “A Chinese Dissident Tried to Fly to His Sick Wife in the U.S. Then He Vanished,” The New York Times, February 2, 2021, nytimes.com/2021/02/02/world/asia/china-dissident-yang-maodong.html Authorities in Guangzhou had confiscated Yang’s passport after his 2019 release from a politically motivated prison sentence. The day before he planned to fly, Yang had written an open letter to President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang, urging them to allow him to travel on humanitarian grounds. Instead, authorities forcibly disappeared him; a year later—and two days after his wife’s death—Yang was formally arrested for “inciting subversion of state power.”15Helen Davidson, “Chinese activist told he could not visit dying wife is re-arrested,” The Guardian, January 18, 2022, theguardian.com/world/2022/jan/18/chinese-activist-yang-maodong-told-he-could-not-visit-dying-wife-is-re-arrested Writer and #MeToo activist Sophia Huang Xueqin, who previously served four months in detention for her public support of sexual assault victims, was also forcibly disappeared while trying to leave China, en route to study at the University of Sussex in England in September 2021. Despite returning Huang’s passport earlier in 2021 and continuing to surveil her for a year after her release, Chinese authorities secretly detained Huang in RSDL and later transferred her to a Guangzhou detention facility for “inciting subversion of state power.16Alice Su, “They helped Chinese women, workers, the forgotten and dying. Then they disappeared,” Los Angeles Times, December 1, 2021, latimes.com/world-nation/story/2021-12-01/china-disappearances-gender-labor-class The trial of writer and poet Xie Fengxia, for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” began in April 2021. Just two years prior, Xie was released from prison; but he was surveilled, followed by local authorities, and “invited” for questioning at police stations following his release. After posting a poem commemorating Lin Zhao, a dissident of the Cultural Revolution, he was promptly detained again.17“185. Xie Fengxia,” Independent Chinese PEN Center, accessed February 24, 2022, chinesepen.org/english/185-xie-fengxia

In Hong Kong, several writers were newly detained in 2021, raising the number of writers and public intellectuals jailed from last year’s three to five. The crackdown under the draconian National Security Law borrows a tactic from Beijing’s repression of free expression, resting on ambiguously defined national security crimes.18Javier C. Hernández, “Harsh Penalties, Vaguely Defined Crimes: Hong Kong’s Security Law Explained,” June 30, 2020, nytimes.com/2020/06/30/world/asia/hong-kong-security-law-explain.html Under the law’s provisions, Hong Kong authorities have detained columnists, academics, and public intellectuals who have written in support of pro-democracy protests, and levied heavy penalties against the institutions that stand by them. A number of individuals who were prominent in the 2014 Occupy Central Movement in Hong Kong were also re-detained or newly charged under the repressive provisions of the National Security Law. Legal scholar and influential pro-democracy writer Benny Tai Yiu-ting was re-detained after a revocation of his bail stemming from a 2019 politically motivated detention.19Jasmine Siu, “Benny Tai sent back to jail to await Hong Kong court’s ruling in Occupy Central appeal,” South China Morning Post, March 4, 2021, sg.news.yahoo.com/benny-tai-sent-back-jail-095645191.html Social media activist and writer Joshua Wong, who rose to prominence as a youth activist when he was first charged in 2015, faced a slew of new charges brought against him during the year under the National Security Law, in addition to past charges that kept him imprisoned throughout the year.20Reuters, “Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong jailed an additional 10 months over June 4 assembly,” CNBC, May 6, 2021, cnbc.com/2021/05/06/hong-kong-activist-joshua-wong-jailed-an-additional-10-months-over-june-4-assembly.html

The highly publicized closure of pro-democracy newspaper Apple Daily served as a bellwether of media censorship and arrests of writers. On June 17, 2021, 500 police officers raided the newspaper’s office, seized journalistic materials, and froze millions of assets.21“HK’s Apple Daily raided by 500 officers over national security law,” Reuters, June 17, 2021, reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/hong-kongs-apple-daily-newspaper-says-police-arrest-five-directors-2021-06-16 One of the first targets of the law when it was first implemented in 2020 was Apple Daily’s founder, publisher, and opinion writer Jimmy Lai, who spent the entirety of 2021 in jail. The paper’s five most senior staff were eventually arrested.22Iain Marlow, “The Assault on Apple Daily,” Bloomberg, February 3, 2022, bloomberg.com/features/2022-apple-daily-china-hong-kong-crackdown Apple Daily chief editorial writer Yeung Ching-kei and columnist Fung Wai-kong were detained less than 10 days after the raid and arrested on suspicion of violating the National Security Law.23Helen Davidson, “Hong Kong police arrest editorial writer at Apple Daily newspaper,” The Guardian, June 23, 2021, theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/23/hong-kong-police-arrest-editorial-writer-at-apple-daily-newspaper; Helen Davidson, “Hong Kong police arrest senior Apple Daily journalist at airport,” The Guardian, June 27, 2021, theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/28/hong-kong-police-arrest-apple-daily-journalist-airport-fung-wai-kong Eleven days later, the reader-funded and independent Stand News preemptively removed all of its columnists and opinion writing published before May. At the end of 2021, Stand News was also raided and shut down by the Hong Kong authorities.24“Security law: Stand News opinion articles axed, directors resign amid reported threats to Hong Kong digital outlets,” Hong Kong Free Press, June 28, 2021, hongkongfp.com/2021/06/28/security-law-stand-news-opinion-articles-axed-directors-resign-amid-reported-threats-to-hong-kong-digital-outlets/; “Hong Kong pro-democracy Stand News closes after police raids condemned by U.N., Germany,” Reuters, December 29, 2021, reuters.com/business/media-telecom/hong-kong-police-arrest-6-current-or-former-staff-online-media-outlet-2021-12-28

Hong Kong police have also targeted libraries in an attempt to bar access to pro-democracy writing and quash the potential spread of public dissent. When the law was first implemented in the summer of 2020, books by Wong were swiftly removed.25Agence France-Presse, “Democracy books disappear from Hong Kong libraries, including title by activist Joshua Wong,” Hong Kong Free Press, July 4, 2020, hongkongfp.com/2020/07/04/democracy-books-disappear-from-hong-kong-libraries-including-title-by-activist-joshua-wong In the summer of 2021, an inquiry was launched into Shek Tong Tsui Public Library after it featured books written by Jimmy Lai on a “librarian’s choice” shelf. The inquiry resulted in one unnamed librarian’s suspension and the prohibition of lending any book titles that a government department believed breached the National Security Law.26Ng Kang-chung, “Hong Kong librarian suspended after books by jailed Apple Daily founder Jimmy Lai put on recommended reading shelf,” South China Morning Post, July 1, 2021, sg.news.yahoo.com/hong-kong-librarian-suspended-books-114304238.html Later in the summer, five unnamed members of a speech therapists’ union were arrested for creating and publishing three electronic children’s books that illustrated the 2019 pro-democracy protests using imagery of sheep and wolves.27Agence France-Presse, “Five arrested in Hong Kong for sedition over children’s book about sheep,” The Guardian, July 22, 2021, theguardian.com/world/2021/jul/22/five-arrested-in-hong-kong-for-sedition-over-childrens-book-about-sheep In the face of these detentions and imprisonments, concerns about running afoul of the ambiguously defined crimes of the National Security Law have resulted in a tangible atmosphere of self-censorship. At the 2021 Hong Kong Book Fair—the first since 2019—books that could potentially be considered politically risky were culled from display, as publishers and exhibitors reportedly exercised a new spirit of self-discipline in curating their selections.28Sara Cheng and Joyce Zhou, “Self-censorship expected as Hong Kong book fair held under national security law,” Reuters, July 13, 2021, reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/self-censorship-expected-hong-kong-book-fair-held-under-national-security-law-2021-07-13 In preparation for the fair, one participating publisher said, “[W]e self-censor a lot this time. We read through every single book and every single word before we bring it here.”29Associated Press, “Self-censorship hits Hong Kong book fair in wake of national security law,” The Guardian, July 15, 2021, theguardian.com/books/2021/jul/15/self-censorship-hits-hong-kong-book-fair-in-wake-of-national-security-law

Legal charges brought against writers in the Tibetan Autonomous Region are often related to spurious national security crimes, or undisclosed to the public.

In Tibet, the number of writers and public intellectuals detained or imprisoned during 2021 increased from six to eight. Writers and public intellectuals are commonly detained for reasons ranging from critically responding to state encroachments on Tibetan language and education, to alleged displays of support for the Dalai Lama, to broader expressions of support for free expression or denunciations of censorship. The charges brought against them are often related to spurious national security crimes, or are undisclosed to the public. In March 2021, writer Gangkye Drubpa Kyab—a poet, teacher, former political prisoner, and author of books on the 2008 Tibetan unrest—was arrested in Kardze, but his whereabouts and the charges against him remain unknown.30Choekyi Lhamo, “Chinese police detain six noted Tibetans in Kardze,” Phayul, April 15, 2021, phayul.com/2021/04/15/45489 Prominent writer Go Sherab Gyatso disappeared in October 2020, and later appeared in state custody in the Tibetan Autonomous Region. In 2021 the Chinese government responded to a United Nations request for further information about Go Sherab Gyatso’s incommunicado detention and reasons for his arrest, claiming that he was detained for “inciting secession.” Four months later, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison on the charge, which rights groups and his relatives believe is in connection with his writing that touched on Tibetan politics and free expression.31“Arbitrarily detained Tibetan Scholar, Go Sherab Gyatso covertly sentenced to 10 years,” Central Tibetan Administration, December 16, 2021, tibet.net/arbitrarily-detained-tibetan-scholar-go-sherab-gyatso-covertly-sentenced-to-10-years; Lhuboom, “Tibetan writer given 10-year prison term in secret trial,” Radio Free Asia, December 10, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/tibet/trial-12102021135859.html; “China: Release Tibetan scholar Gō Sherab Gyatso from arbitrary detention,” Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy, April 16, 2021, tchrd.org/china-release-tibetan-scholar-go-sherab-gyatso-from-arbitrary-detention In a similarly clandestine fashion, poet and writer Gendun Lhundrub has remained in detention without trial or public information about his arrest since December 2020.32“Qinghai monk writer missing for more than a year after Chinese ‘arrest’,” Tibetan Review, January 26, 2022, tibetanreview.net/qinghai-monk-writer-missing-for-more-than-a-year-after-chinese-arrest

The majority of cases in Tibet include writers who have been imprisoned for multiple years. Well-known online writer and editor of the first-ever Tibetan literary website Chomei, Kunchok Tsephel Gopey Tsang had been in prison since 2009 for “leaking state secrets.” While no evidence for this charge has been made public, it is likely related to his website and writing focused on Tibetan literature; Chomei had been censored online prior to Kunchok Tsephel Gopey Tsang’s imprisonment.33“Founder of Tibetan cultural website sentenced to 15 years in closed-door trial in freedom of expression case,” International Campaign for Tibet, November 16, 2009, savetibet.org/founder-of-tibetan-cultural-website-sentenced-to-15-years-in-closed-door-trial-in-freedom-of-expression-case; “Tibetan Literary Website Founder Sentenced to 15 Years in Prison,” Free Tibet, accessed March 11, 2022, freetibet.org/freedom-for-tibet/political-prisoners/case-studies/kunchok-tsephel/ Monk and online writer Jo Lobsang Jamyang has been serving a seven-year and six-month sentence for “leaking state secrets” since 2015. Tibetans familiar with Jamyang’s writing suspect that his articles on free expression and environmental degradation and debates with other Tibetan writers may have led to his imprisonment.34“Lobsang Jamyang,” Committee to Protect Journalists, accessed March 22, 2022, cpj.org/data/people/lobsang-jamyang Further details are unknown, as Jamyang was convicted in secret by a Wenchuan county court in Ngaba prefecture.35Yeshe Choesang, “Tibetan writer Lomig is handed 7-year term on unknown charges,” The Tibet Post, May 9, 2016, thetibetpost.com/en/news/tibet/5000-tibetan-writer-lomig-is-handed-7-year-term-on-unknown-charges; Tenzin Gaphel, “Tibetan writer Lomig arbitrarily arrested in restive Ngaba County,” Tibet Express, April 22, 2015, tibetexpress.net/1265/tibetan-writer-lomig-arbitrarily-arrested-in-restive-ngaba-county Multiple songwriters, including Trinley Tsekar, Khado Tsetan, and Lhundrub Drakpa, also remain detained for writing lyrics that explore Tibetan identity, culture, and critical opinions of the Chinese government’s policies.36“China imprisons two Tibetans for song praising His Holiness the Dalai Lama,” Central Tibetan Administration, July 21, 2020, tibet.net/china-imprisons-two-tibetans-for-song-praising-his-holiness-the-dalai-lama; “China sentences Tibetan singer to six years in prison,” Central Tibetan Administration, October 30, 2020, tibet.net/china-sentences-tibetan-singer-to-six-years-in-prison

Many writers and public intellectuals at the helm of institutions like magazines and publishing houses have been detained or imprisoned, effectively criminalizing institutions of literature and culture.

In Xinjiang, the brutal repression of Uyghur and other Turkic minorities alongside the crackdown on cultural institutions has continued. At least 34 writers and public intellectuals were detained or imprisoned for their writing and work in the region during 2021, almost as many as in the rest of China. However, as noted in previous years’ reports, this figure is certainly an incomplete accounting of the actual number. As human rights groups actively work to document the scale of internment in Xinjiang, efforts are stymied by the government’s censorship of domestic media, restricted foreign media access, and pervasive surveillance.37For additional information on the detention of writers, intellectuals, and other cultural figures in Xinjiang, see the following reports from the Uyghur Human Rights Project: Detained and Disappeared: Intellectuals Under Assault in the Uyghur Homeland, March 25, 2019, uhrp.org/report/detained-and-disappeared-intellectuals-under-assault-uyghur-homeland-html; UHRP Update: The Persecution of the Intellectuals in the Uyghur Region Continues, January 28, 2019, uhrp.org/report/persecution-intellectuals-uyghur-region-continues-html; UHRP Report: The Persecution of the Intellectuals in the Uyghur Region: Disappeared Forever?, October 2018, uhrp.org/report/persecution-intellectuals-uyghur-region-disappeared-forever-html During 2021, information leaks from a police database in Ürümqi further revealed how Muslims and ethnic minorities—such as Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and Kyrgyz—are systematically surveilled through the collection of online communication, mobile phone data, and location data.38Yael Grauer, “Revealed: Massive Chinese Police Database,” The Intercept, January 29, 2021, theintercept.com/2021/01/29/china-uyghur-muslim-surveillance-police Writers who publish in their native languages and support literary institutions have been detained on spurious national security crimes of “extremism” and “separatism,” or have yet to be given any reason at all for their arrest.

Many writers and public intellectuals at the helm of institutions like magazines and publishing houses have been detained or imprisoned, effectively criminalizing institutions of literature and culture. Qurban Mamut, a Uyghur poet and longtime editor of culture journal Xinjiang Civilization, went missing in 2017 and was later confirmed to have been detained. Despite working within the confines of state censorship at Xinjiang Civilization, Mamut went missing a few months after he visited his son Bahram Sintash, who lives in the United States.39Austin Ramzy, “China Targets Prominent Uighur Intellectuals to Erase an Ethnic Identity,” The New York Times, January 5, 2019, nytimes.com/2019/01/05/world/asia/china-xinjiang-uighur-intellectuals.html; “Qurban Mamut, a retired Uyghur editor held incommunicado in China,” Uyghur PEN, accessed March 1, 2022, uyghurpen.org/qurban-mamut-a-retired-uyghur-editor-held-incommunicado-in-china Tashpolat Tiyip—the former president of Xinjiang University, geography professor, and author of five books—also went missing in 2017 after he left Xinjiang for Germany to attend a conference. Two years after his disappearance, the UN urged the Chinese government to disclose his location and clarify the terms of his imprisonment. He has reportedly been held on separatism charges, and his family has received reports that he received a suspended death sentence, though the Chinese government has refuted this, claiming he was detained under corruption charges and not subject to a death sentence.40“China urged to disclose location of Uyghur academic Tashpolat Tiyip,” Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, December 26, 2019, ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2019/12/china-urged-disclose-location-uyghur-academic-tashpolat-tiyip; Amy Anderson, “Death sentence for a life of service,” Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, January 22, 2019, u.osu.edu/mclc/2019/01/25/death-sentence-for-a-life-of-service; “President of Xinxiang University Arrested Four Years Ago. Whereabouts Unknown to This Day,” Committee of Concerned Scientists, May 5, 2021, concernedscientists.org/2021/05/president-of-xinxiang-university-arrested-four-years-ago-whereabouts-unknown-to-this-day At least five writers and public intellectuals who worked at the Kashgar Publishing House remained in detention during 2021. Deputy editor-in-chief Ablajan Siyit; editor Memetjan Abliz Boriyar; two retired editors-in-chief, Osman Zunun and Abliz Ömer; and retired editor and poet Haji Mirzahid Kerimi were all arrested in 2017 and 2018 for their involvement in publishing books deemed “problematic.”41Shohret Hoshur, “Veteran Editor of Uyghur Publishing House Among 14 Staff Members Held Over ‘Problematic Books’,” Radio Free Asia, November 26, 2018, rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/editor-11262018155525.html Tragically, retired editor Kerimi died on January 9, 2021 while serving his prison sentence.42Shohret Hoshur, “Prominent Uyghur Poet and Author Confirmed to Have Died While Imprisoned,” Radio Free Asia, January 25, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/poet-01252021133515.html

A sizeable 16 of the 34 writers PEN America documented as detained or imprisoned in Xinjiang in 2021 are also scholars of Uyghur literature, folklore, and politics. Historical researcher, literary critic, and writer Yalqun Rozi has been in prison since 2016 and is serving a 15-year sentence for his role in compiling and editing Uyghur literature textbooks that Chinese authorities claimed were “separatist.”43Helen Davidson, “China hands death sentences to Uyghur former officials,” The Guardian, April 9, 2021, theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/09/china-uyghur-death-sentences-xinjiang-education-directors Prominent folklorist and ethnographer Rahile Dawut has been in detention since 2017 after she attempted to travel from Ürümqi to Beijing. Dawut’s scholarship focuses on minority cultures and sacred Islamic sites in Central Eurasia; she founded the Minorities Folklore Research Centre at Xinjiang University and has authored several books and scholarly articles.44“Uyghur Scholar Rahile Dawut Named Honorary Professor in the Humanities by the Open Society University Network,” Bard News, December 8, 2020, bard.edu/news/rahile-dawut-named-first-osun-honorary-professor-in-the-humanities-2020-12-08 Former coworkers of Dawut’s confirmed her imprisonment in July 2021, while the Chinese government has yet to release information to the public or her family.45Shohret Hoshur and Gulchehra Hoja, “Noted Uyghur Folklore Professor Serving Prison Term in China’s Xinjiang,” Radio Free Asia, July 13, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/rahile-dawut-07132021175559.html Reported retaliation for speaking publicly about these cases coupled with a lack of press freedom in Xinjiang results in delayed public knowledge around many cases of jailed writers. In August 2021, three coworkers of another Xinjiang University professor, Gheyratjan Osman, confirmed that Osman was detained in 2018 and currently serving 10 years in prison for “separatism.” Osman was a literature professor who published dozens of books and hundreds of scholarly articles on Uyghur language and folklore.46“Urgent Actions Needed to Stop Cultural Rights Violations Against Uyghurs,” Chinese Human Rights Defenders, October 5, 2021, nchrd.org/2021/10/urgent-actions-needed-to-stop-cultural-rights-violations-against-uyghurs Finally, 2021 marked the seventh year that Uyghur economist, online writer, and 2014 PEN Freedom to Write honoree Ilham Tohti has been held in Chinese state custody for his writings intended to foster understanding between Uyghurs and Han Chinese.47Andrew Jacobs, “China Charges Scholar With Inciting Separatism,” The New York Times, February 26, 2014, nytimes.com/2014/02/27/world/asia/ilham-tohti.html While Tohti is not imprisoned in Xinjiang, his unjust imprisonment is emblematic of the treatment many Uyghur writers face. He has been imprisoned incommunicado for the last five years and has been permitted no contact with his family or lawyers. Tohti’s daughter Jewher Ilham has nevertheless advocated fervently for his release, bringing attention to tragically similar accounts of unjustly detained Uyghurs and other political prisoners in Xinjiang.48Colm Keena, “‘We don’t know if he is alive’: Uighur woman speaks out on jailing of father in Xinjiang,” Irish Times, April 29, 2021, irishtimes.com/news/world/asia-pacific/we-don-t-know-if-he-is-alive-uighur-woman-speaks-out-on-jailing-of-father-in-xinjiang-1.4551124

Saudi Arabia

In Saudi Arabia, the number of writers either detained or imprisoned during 2021 remained high but stable, with a slight decrease to 29 behind bars and only one new detention counted during the year. Eminent scholar Saud Al-Sarhan, who has written commentary on Saudi public affairs and Yemeni politics, went missing in late October 2021. It was revealed only on December 7, 2021, that Al-Sarhan had been held incommunicado by Saudi authorities without published cause.49“Saudi academic Saud al-Sarhan missing since October,” ALQST, July 12, 2021, alqst.org/en/post/saudi-academic-saud-al-sarhan-missing Human rights groups surmise that his arrest was due to an article he wrote commenting negatively on the leadership of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.50Saud Al-Sarhan, “Vision 2030: A dawn that dispels doubts,” Al Arabiya News, April 26, 2021, english.alarabiya.net/in-translation/2021/04/26/Vision-2030-A-dawn-that-dispels-doubts; “Saudi academic Saud al-Sarhan missing since October,” ALQST, July 12, 2021, alqst.org/en/post/saudi-academic-saud-al-sarhan-missing

The majority of cases in Saudi Arabia represent writers and public intellectuals who have been in prison for extended periods of time;51“Abuses Under Scrutiny: Human Rights in Saudi Arabia,” ALQST, accessed March 17, 2021, alqst.org/uploads/Abuses-Under-Scrutiny-En.pdf many have been in custody for five years or longer. Saudi authorities have held blogger Fadhel Al-Manasef, for example, in some form of state custody since 2011 and he is currently serving a 14-year jail sentence, slightly reduced from the original 15 years handed down in 2014.52“Case History: Fadhel Mekki Al-Manasef,” Front Line Defenders, accessed March 22, 2021, frontlinedefenders.org/en/case/case-history-fadel-mekki-al-manasef Raif Badawi, a blogger and creator of the Free Saudi Liberals website—who was detained in 2012 and eventually sentenced on appeal in 2014 to 10 years in prison and 1,000 lashes, as well as handed down a fine of 1 million Saudi riyals—remained in jail throughout 2021.53“Raif Badawi,” Committee to Protect Journalists, accessed March 18, 2021, cpj.org/data/people/raif-badawi/ His sentence expired on February 28, 2022, but Saudi officials refused to release him then; after renewed calls for his release, he was freed on March 11, but remains subject to a 10-year travel ban and restrictions on his professional activities and writing.54“Saudi blogger Raif Badawi still held after completing 10-year jail term,” Reporters Without Borders, March 1, 2022, rsf.org/en/news/saudi-blogger-raif-badawi-still-held-after-completing-10-year-jail-term; “Saudi Arabia confirms 10-year travel ban for freed blogger Raif Badawi,” France 24, March 12, 2022, france24.com/en/live-news/20220312-saudi-arabia-confirms-10-year-travel-ban-for-freed-blogger-raif-badawi Online commentator Fahad Al-Fahad, arrested in 2016 for tweets that criticized the justice system and government corruption, was sentenced in 2017 to five years’ imprisonment, a 10-year travel ban, and a ban on writing and media work that the presiding judge said was for life.55“Saudi Arabia: Activist Marks 2 Years Behind Bars,” Human Rights Watch, April 5, 2018, hrw.org/news/2018/04/05/saudi-arabia-activist-marks-2-years-behind-bars A significant portion of jailed writers in the Kingdom are being detained indefinitely without any charge; cases include journalist and online commentator Adel Banaima, arrested in September 2017; writer and online commentator Maha Al-Rafidi Al-Qahtani, held since September 2019 and subjected to custodial abuse; and journalist and scholar Zuhair Kutbi, detained in January 2019.56“Adel Banaima,” ALQST, accessed March 21, 2022, alqst.org/en/prisonersofconscience/adel-banaima; “Ongoing detention of female journalist and writer Maha al-Rafidi confirmed,” ALQST, January 14, 2020, alqst.org/en/ongoing-detention-female-journalist-writer-maha-al-rafidi-confirmed; “Zuhair Kutbi,” Committee to Protect Journalists, accessed March 21, 2022, cpj.org/data/people/zuhair-kutbi/

Despite a flurry of releases in 2021, many of the dissident Saudi writers and intellectuals released then and in the past several years continue to face significant conditions on their speech and movement that have prevented them from enjoying full freedom or returning to their writing or professional life. Threats of significant repercussions hang over them, should they breach the often-broad conditions of their freedom.57Arwa Youssef, “Saudi Women’s Rights Defenders Released, But Not Free,” Human Rights Watch, February 12, 2021, hrw.org/news/2021/02/12/saudi-womens-rights-defenders-released-not-free Many also face lingering legal charges or ongoing trials. These cases include many women who have advocated for women’s rights through their writings, such as academic Hatoon Al-Fassi and professor and columnist Eman Al-Nafjan, both released in 2019, as well as writer-activists Loujain Al-Hathloul, Nouf Abdulaziz, and Nassima Al-Sadah, released in early 2021 after being jailed for nearly three years.58“Saudi journalist Hatoon al-Fassi freed provisionally,” Reporters Without Borders, May 10, 2019, rsf.org/en/news/saudi-journalist-hatoon-al-fassi-freed-provisionally; Stephen Kalin and Sarah Dadouch, “Saudi Arabia temporarily frees three women activists,” Reuters, March 28, 2019, reuters.com/article/us-saudi-arrests/saudi-arabia-temporarily-frees-three-women-activists-idUSKCN1R91S6; Nadda Osman, “Loujain al-Hathloul: Saudi activist released from prison,” Middle East Eye, February 10, 2021, middleeasteye.net/news/saudi-arabia-loujain-hathloul-activist-returns-home-prison; “Saudi Arabia releases two prominent women’s rights activists,” Al Jazeera, June 27, 2021, aljazeera.com/news/2021/6/27/saudi-arabia-releases-two-prominent-womens-rights-activists Al-Hathloul, who had been detained since May 2018, was denied her request to appeal her conviction.59“Saudi appeals court rejects rights activist claim she was tortured in jail, family says,” Reuters, February 9, 2021, reuters.com/article/saudi-rights-women-justice-int/saudi-appeals-court-rejects-rights-activist-claim-she-was-tortured-in-jail-family-says-idUSKBN2A91X0 Upon release, she was placed under strict travel restrictions as well as what amounted to a gag order prohibiting her from speaking about the case or celebrating her release publicly.60“Saudi travel ban on activists and their families stirs unease even as detainees are released,” The Straits Times, February 24, 2021, straitstimes.com/world/middle-east/saudi-travel-bans-on-activists-and-families-stir-unease-as-detainees-released; “Saudi court upholds rights activist al-Hathloul’s sentence at appeals hearing,” Reuters, March 10, 2021, reuters.com/article/uk-saudi-rights-women-idUKKBN2B20QW; “Saudi court confirms Loujain al-Hathloul sentence,” Deutsche Welle, March 10, 2021, dw.com/en/saudi-court-confirms-loujain-al-hathloul-sentence/a-56826103 In March 2021, local human rights groups confirmed the release of journalist and blogger Ali Al-Saffar, journalist and blogger Thumar Al-Marzouqi, novelist Moqbel Al-Saqqar, and scholar and journalist Redha Al-Boori, all of whom had been arrested in an April 2019 sweep.61“Saudi Arabia releases prisoners of conscience not known to public,” Middle East Monitor, March 6, 2021, middleeastmonitor.com/20210306-saudi-arabia-releases-prisoners-of-conscience-not-known-to-public; ALQST for Human Rights (@ALQST_En), “ALQST has news of further releases of those detained in April 2019,” Twitter status, March 12, 2021, twitter.com/alqst_en/status/1370353985719271427; “Saudi Arabia: New wave of arrests targeting human rights community must stop,” The Gulf Center for Human Rights, April 4, 2019, gc4hr.org/news/view/2111 In July, writer and professor Aql Al-Bahili and writer and economist Abdulaziz Al-Dukhail, two of the three writers detained in April 2020 after expressing condolences online for deceased activist Abdullah Al-Hamid, were released, but it was unclear if any conditions were placed on their freedom.62ALQST for Human Rights (@ALQST_En), “Aql al-Bahili, detained since April 2020 for expressing sympathy over the death of rights activist Abdullah al-Hamid, has been released,” Twitter status, July 14, 2021, twitter.com/alqst_en/status/1415366553525174273; “Saudi official released after year-long detention over tweet,” Middle East Eye, July 9, 2021, middleeasteye.net/news/saudi-arabia-official-released-after-year-long-detention-over-tweet

Many of the Saudi writers and intellectuals released during 2021 and in the past several years remain subject to conditions on their speech and movement. Threats of significant repercussions hang over them, should they breach the often-broad conditions of their freedom.

In general, the environment for free expression in Saudi Arabia remains extremely poor, with little movement on some longstanding cases of political prisoners; continued efforts to intimidate Saudi commentators based abroad through online trolling and threats, surveillance, and hacking; and ongoing impunity for past cases of grave abuse perpetrated by the Saudi state, such as the murder of exiled journalist and columnist Jamal Khashoggi.63Stephanie Kirchgaessner, “US finds Saudi crown prince approved Khashoggi murder but does not sanction him,” The Guardian, February 26, 2021, theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/26/jamal-khashoggi-mohammed-bin-salman-us-report

Myanmar

The environment for free expression in Myanmar dramatically worsened in 2021 as a result of the February 1 coup, during which the military seized power; prevented the elected parliament from forming; cut off communications channels and banned media outlets; and arrested dozens of senior politicians, including National League for Democracy (NLD) leadership Senior Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi and President Win Myint, as well as influential cultural figures and creative artists.64“Internet disrupted in Myanmar amid apparent military uprising,” NetBlocks, January 31, 2021, netblocks.org/reports/internet-disrupted-in-myanmar-amid-apparent-military-uprising-JBZrmlB6; “Aung San Suu Kyi and other leaders arrested, party spokesman says,” Reuters, February 1, 2021, news.trust.org/item/20210131230656-kkg7f; “Stolen Freedoms: Creative Expression, Historic Resistance, and the Myanmar Coup,” PEN America, accessed March 21, 2022, pen.org/report/stolen-freedoms-creative-expression-historic-resistance-and-the-myanmar-coup During the year, as part of a broad-based crackdown in which thousands of protesters were jailed and hundreds killed, the number of jailed writers and creative artists increased from 8 in 2020 to 26 in 2021, catapulting Myanmar from ninth place in last year’s Index to third this year. In addition to detentions, which in most cases have been followed eventually by legal charges and sentences under Myanmar’s restrictive laws, writers and public intellectuals have also faced violence, threats, and surveillance, all of which have served to chill expression and the ability to write freely.65“Stolen Freedoms: Creative Expression, Historic Resistance, and the Myanmar Coup,” PEN America, accessed March 21, 2022, pen.org/report/stolen-freedoms-creative-expression-historic-resistance-and-the-myanmar-coup

Arrests of influential writers and cultural luminaries started as soon as the military junta took over, likely because of their consistent support for human rights, as well as the NLD government and opposition to the military: filmmaker Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, previously detained in 2019, was detained on the first night of the coup, alongside singer-songwriter Saw Phoe Khwar and writers Htin Lin Oo, Maung Thar Cho, Mya Aye, and Than Myint Aung.66“Recent Arrest List Last Updated Feb 4,” Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, February 4, 2021, aappb.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Recent-Arrest-List-Last-Updated-on-Feb-4.pdf; “Statement on Recent Detainees in Relation to the Military Coup,” Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, February 4, 2021, aappb.org/?p=12997; “Three Saffron Revolution monks among those detained in February 1 raids,” Myanmar Now, February 3, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/three-saffron-revolution-monks-among-those-detained-in-february-1-raids; “Recent Arrest List CSOs Last Updated Feb 4,” Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, February 4, 2021, aappb.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Recent-Arrest-List-CSOsLast-Updated-on-Feb-4.pdf Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi had been released from prison less than one year earlier, sentenced on charges related to social media posts critical of the military’s constitutional role in politics.67“How Myanmar’s junta used a coup to settle old scores,” Myanmar Now, September 12, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/how-myanmars-junta-used-a-coup-to-settle-old-scores He and Htin Lin Oo, who also had a history of organizing against the army’s political participation, were both able to post warnings on social media prior to their arrests.68Mon Mon Myat, “Myanmar Making Noises for Democracy,” The Irrawaddy, February 8, 2021, irrawaddy.com/opinion/myanmar-making-noises-democracy.html The latter wrote on Facebook, “Now our country is under a military coup for the third time. The democracy we arduously built has been crushed.”69“Aung San Suu Kyi Urges Protests to Reject Myanmar Military Coup, 1-Year State of Emergency,” Radio Free Asia, January 31, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/military-arrests-01312021195220.html Police staked out Maung Thar Cho’s home for hours before detaining him, promising his family that he would only be taken for a short time.70How Myanmar’s junta used a coup to settle old scores,” Myanmar Now, September 12, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/how-myanmars-junta-used-a-coup-to-settle-old-scores; Mon Mon Myat, “Myanmar Making Noises for Democracy,” The Irrawaddy, February 8, 2021, irrawaddy.com/opinion/myanmar-making-noises-democracy.html; Helen Regan and Sandi Sidhu, “By day, Myanmar’s protesters are defiant dissenters. By night, they’re terrified of being dragged from their beds by the junta,” CNN, February 20, 2021, edition.cnn.com/2021/02/19/asia/myanmar-protest-voices-coup-intl-dst-hnk/index.html Instead he was held on unknown charges for over 10 months, including periods of solitary confinement, and in May 2021, he underwent a military interrogation in which he was forced to renounce his public remarks in support of the NLD.71“Stolen Freedoms: Creative Expression, Historic Resistance, and the Myanmar Coup,” PEN America, accessed March 11, 2022, pen.org/report/stolen-freedoms-creative-expression-historic-resistance-and-the-myanmar-coup; “In Military-Ruled Myanmar, Political Detainees Mark 100 Days Behind Bars,” The Irrawaddy, May 11, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/in-military-ruled-myanmar-political-detainees-mark-100-days-behind-bars.html Prominent ’88 Generation activist Mya Aye and writer and NLD representative Than Myint Aung were similarly arrested early in the morning on February 1, 2021.72“How Myanmar’s junta used a coup to settle old scores,” Myanmar Now, September 12, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/how-myanmars-junta-used-a-coup-to-settle-old-scores; Aditi Bhandari, Wa Lone, and Poppy McPherson, “Politicians, doctors and a fortune-teller: Myanmar’s new wave of detainees,” Reuters, March 1, 2021, graphics.reuters.com/MYANMAR-POLITICS/DETENTIONS/jbyvrdaznve Mya Aye was held incommunicado for months before his location and charges were revealed.73“How Myanmar’s junta used a coup to settle old scores,” Myanmar Now, September 12, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/how-myanmars-junta-used-a-coup-to-settle-old-scores All of them remained behind bars at year’s end and have since been handed various charges in retaliation for their writing. For example, Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi was charged with incitement, while Mya Aye was sentenced to two years in prison under Section 505(c) of the penal code for “inciting hate towards an ethnicity or a community,” a charge related to a 2014 email criticizing ethno-nationalism in Myanmar.74“Myanmar Junta Jails Celebrity for Anti-Coup Protests,” The Irrawaddy, December 28, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-junta-jails-celebrity-for-anti-coup-protests.html; Esther J, “Democracy activist Mya Aye receives two-year prison sentence on his birthday,” Myanmar Now, March 10, 2022, myanmar-now.org/en/news/democracy-activist-mya-aye-receives-two-year-prison-sentence-on-his-birthday; Esther J, “Jailed 1988 veteran admitted to hospital with ‘life-threatening’ infection from wound,” Myanmar Now, November 5, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/jailed-1988-veteran-admitted-to-hospital-with-life-threatening-infection-from-wound Than Myint Aung and Htin Lin Oo were sentenced in December and the following February, respectively, to three years in prison under Section 505(a) of the penal code for allegedly opposing the coup online and inciting anti-military sentiments.75Han Thit, “Junta hits author and model with three-year prison sentences,” Myanmar Now, December 29, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/junta-hits-author-and-model-with-three-year-prison-sentences; Esther J, “Writer Htin Lin Oo sentenced to three years in prison,” Myanmar Now, February 22, 2022, myanmar-now.org/mm/news/10532 In February 2022, Maung Thar Cho was sentenced to two years in prison with hard labor, also under Section 505(a), reportedly stemming from two articles that were published a year before the coup took place.76“Writers Maung Thar Cho and Htin Lin Oo sentenced to hard labor,” The Irrawaddy, February 22, 2022, burma.irrawaddy.com/news/2022/02/22/250081.html

Poet, political satirist, and professor Maung Thar Cho has been detained since day one of the military coup in Myanmar.

Within weeks of the coup, a broad-based, countrywide civil disobedience movement (known as the CDM) emerged involving thousands of protesters, who continue to challenge the military’s illegal takeover and fight for their country’s future. As writers’ groups and other creative artists have played a key role in the CDM, they have been targeted for arrest and legal charges—and in some cases, they have been killed—for their civic activism and for inspiring others to join the movement.77The leading role of writers and creative artists in the CDM can be explored further in PEN America’s December 2021 report, Stolen Freedoms: Creative Expression, Historic Resistance, and the Myanmar Coup, available at: pen.org/report/stolen-freedoms-creative-expression-historic-resistance-and-the-myanmar-coup At least six poets were arrested and detained for their participation in poet-led protests in downtown Yangon on Pansodan Road, where they held poetry recitals and sold art to support civil resistance in the weeks immediately after the coup.78Mon Mon Myat, “Is Civil Disobedience Myanmar’s New Normal?,” The Irrawaddy, February 15, 2021 irrawaddy.com/opinion/civil-disobedience-myanmars-new-normal.html; Tommy Walker, “How Myanmar’s Civil Disobedience Movement Is Pushing Back Against the Coup,” Voice of America, February 27, 2021, voanews.com/a/east-asia-pacific_how-myanmars-civil-disobedience-movement-pushing-back-against-coup/6202637.html; “PEN America Condemns Myanmar Military Regime’s Deadly Use of Force,” PEN America, March 4, 2021, pen.org/press-release/pen-america-condemns-myanmar-military-regimes-deadly-use-of-force Wai Moe Naing, a writer and activist also known as Monywa Panda, was attacked and then arrested at a protest in April, and later charged with incitement under Section 505(a) of the penal code, and nine other serious charges, including treason, armed robbery, and murder.79“Wai Moe Naing, prominent leader of anti-coup movement, detained in Monywa,” Myanmar Now, April 15, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/wai-moe-naing-prominent-leader-of-anti-coup-movement-detained-in-monywa; “Detained protest leader Wai Moe Naing meets with his lawyer for the first time, says mother,” Myanmar Now, May 29, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/detained-protest-leader-wai-moe-naing-meets-with-his-lawyer-for-the-first-time-says-mother Poet Khet Thi, who had rallied protesters with his words and writings, was detained and reportedly tortured to death after being taken into custody in central Myanmar.80“Torture Suspected in Death of Myanmar Poet Called a Voice of Resistance,” Radio Free Asia, May 11, 2021, rfa.org/english/news/myanmar/poet-05112021185408.html According to his wife, after his detention his body was returned to his family with missing organs.81“Body of arrested Myanmar poet Khet Thi returned to family with organs missing,” The Guardian, May 9, 2021, theguardian.com/world/2021/may/10/body-of-arrested-myanmar-poet-khet-thi-returned-to-family-with-organs-missing

Civil resistance to the coup continued despite the military’s violent repression, which escalated after the first few weeks following the coup; reactive and preemptive arrests of writers continued as well. Maung Yu Py, a well-known poet from Myeik, was detained on March 9 alongside several dozen activists amid widespread reports of torture in custody.82Mark Frary, “Myanmar keeps it poets locked up despite prisoner release,” Index on Censorship, July 2, 2021, indexoncensorship.org/2021/07/myanmar-keeps-it-poets-locked-up-despite-prisoner-release; “More than 30 youth sentenced in closed court hearing inside Myeik Prison,” Myanmar Now, June 10, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/more-than-30-youth-sentenced-in-closed-court-hearing-inside-myeik-prison On April 6, the prominent satirist and film director Zarganar was arrested under unknown charges; like Htin Lin Oo, Zarganar had also written critically about the coup on Facebook after the military first seized power in February.83“Comedian Zarganar arrested by junta,” Myanmar Now, April 6, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/comedian-zarganar-arrested-by-junta On April 24, fiction writer and journalist Tu Tu Tha was arrested in a home raid by at least 10 military soldiers.84“Myanmar’s Junta Continues to Arrest Journalists,” The Irrawaddy, April 26, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmars-junta-continues-arrest-journalists.html Both Tu Tu Tha and Zarganar were released in a general amnesty in October 2021, just days after the announcement of the exclusion of coup leader Min Aung Hlaing from the ASEAN summit.85“Senior NLD Official, Prominent Myanmar Comedian Freed Alongside Activists, Journalists,” The Irrawaddy, October 19, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/senior-nld-official-prominent-myanmar-comedian-freed-alongside-activists-journalists.html Despite being released by the military, political prisoners in Myanmar remain at risk of being rearrested any moment; many of those freed in the October general amnesty were swiftly detained once more, while others—including Zarganar—report continued restrictions on their liberties.86“Myanmar Amnesty Ends in Tears as Regime Rearrests Political Prisoners,” The Irrawaddy, October 21, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-amnesty-ends-in-tears-as-regime-rearrests-political-prisoners.html Maung Yu Py, however, was sentenced in a makeshift prison court for unlawful assembly and spreading false news under Section 505A to two years in prison, later reduced to one year.87Mark Frary, “Myanmar keeps it poets locked up despite prisoner release,” Index on Censorship, July 2, 2021, indexoncensorship.org/2021/07/myanmar-keeps-it-poets-locked-up-despite-prisoner-release; “More than 30 youth sentenced in closed court hearing inside Myeik Prison,” Myanmar Now, June 10, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/more-than-30-youth-sentenced-in-closed-court-hearing-inside-myeik-prison This vague provision of “spreading false news” was added as Section 505A of the penal code within several weeks of the coup and was used to charge a number of writers, public intellectuals, and journalists in 2021, including Maung Yu Py and American journalist Danny Fenster.88The Penal Code amendment adds a new crime under Section 505A of “causing fear” or “spreading false news” with a maximum sentence of three years in prison and a fine. “Myanmar Ruling Council Amends Treason, Sedition Laws to Protect Coup Makers,” The Irrawaddy, February 16, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-ruling-council-amends-treason-sedition-laws-protect-coup-makers.html; Han Thit, “Detained American journalist Danny Fenster hit with new charge under Immigration Act,” Myanmar Now, November 4, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/detained-american-journalist-danny-fenster-hit-with-new-charge-under-immigration-act

Six members of the satirical poetry troupe Peacock Generation made up the bulk of Myanmar’s cases counted in the Index prior to 2021, having been charged with incitement against the military and online defamation in 2019.89“Freedom to Write Index 2020,” PEN America, accessed March 21, 2022, pen.org/report/freedom-to-write-index-2020; “Peacock Generation: Satirical poets jailed in Myanmar,” BBC News, October 30, 2019, bbc.com/news/world-asia-50238031 Three were released in 2020, and in a wave of pardons traditionally undertaken to mark Thingyan (the Burmese Buddhist New Year festival), Paing Pyo Min, Zay Yar Lwin, and Paing Ye Thu were released along with hundreds of other political prisoners in April 2021.90Zaw Zaw Htwe, “Jailed Satirical Performer Faces Extra Charge from Myanmar’s Military,” The Irrawaddy, December 16, 2020, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/jailed-satirical-performer-faces-extra-charge-myanmars-military.html; “Nine activists among more than 23,000 freed as part of Thingyan amnesty,” Myanmar Now, April 17, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/nine-activists-among-more-than-23000-freed-as-part-of-thingyan-amnesty Regardless of this show of amnesty, even those previously released faced continued harassment: troupe member Zaw Lin Htut, released in October 2020, was arrested again in December 2021 and faces new charges of incitement.91Han Thit, “Two Yangon activists charged and sent to Insein Prison,” January 17, 2022, myanmar-now.org/en/news/two-yangon-activists-charged-and-sent-to-insein-prison

Though I have different views than you, I’ll lay down my life for you all.

K Za Win