Stolen Freedoms

Creative Expression, Historic Resistance, and the Myanmar Coup

Executive Summary

On February 1, 2021, Myanmar’s military launched a violent coup to overthrow the country’s democratically-elected government in response to the landslide November 2020 electoral victory of Myanmar’s de facto leader, State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and her political party, the National League for Democracy.

Creative artists, including writers, poets, filmmakers, painters, musicians, satirists, graphic artists, and others, have been among the vanguard of the public response to the coup, using their creative tools to denounce the coup, to defend the freedoms gained during the country’s 10-year political opening, and to call for greater change. They have built upon decades of creative protest in Myanmar, from the popular and outspoken pro-independence songs of the 1930s, to the elusive but subversive poetry of the 1970s and 1988, to the mocking satire of the early 2000s.

The military’s retaliation to this public response has been swift and violent.

PEN America’s report Stolen Freedoms: Creative Expression, Historic Resistance, and the Myanmar Coup explores the creative response to the coup and the military’s retaliatory crackdown, framing it within Myanmar’s long history of creative expression and protest. The report reflects extensive research, including a database of specific cases of repression and in-depth interviews with 21 creative artists that document their experiences and perspectives.

The coup’s immediate impact on the creative sector was devastating, with most galleries, art schools, associations, independent television channels, and other creative institutions closed down or forced underground. Yet, creative expression flooded the streets and digital space, often led by members of “Gen Z” who grew up during the political opening and who had no desire to return to the dark era that their parents so loathed and defied. Social media platforms abounded with illustrations, poetry, and music. Silent protests, satirical street theater, temporary public sculptures, and evocative graffiti filled public spaces.

Creative artists have used their work and influence to further the movement to resist military dictatorship, creating and disseminating art both on and offline. Meanwhile, creative expression unrelated to the coup has largely disappeared from the public discourse, as many creative artists have switched their attention to the movement at the expense of less publicly palatable non-political themes. Even so, artists also represent rapidly evolving social norms and advocacy for broader change through their work, in some cases pressing for a more tolerant Myanmar.

Vibrant creation has faced violent oppression, with targeted detentions and extrajudicial killings, alongside the military’s broader arbitrary crackdowns. PEN America has identified at least 45 creative artists who have been detained since the coup started, with many more being hunted and targeted for arrest, or forced to flee into hiding or exile. At least five have been brutally killed and many more have been subjected to abuse and torture. The third wave of COVID-19, exacerbated by the military’s mismanagement and attacks on healthcare workers, has further devastated the creative sector, with the loss of many artists, writers, musicians, and actors.

The military has attempted to prevent online communication and organization: repeatedly shutting or slowing down internet access, blocking websites, and trying to force telecommunications companies to ramp up surveillance—all of which have affected the ability of creative artists to access information, share their work, and speak and create freely.

Many creative artists have taken substantial measures to protect themselves and those around them, including, for some, relocation, and others, anonymity, ensuring that they can keep working while reducing the likelihood that their works will be traced back to them.

Some creative artists are struggling with mental health issues caused by the coup. Guilt that creative expression is never “enough” drives them onwards. Battling widespread insecurity and the constant fear of raids, they describe experiencing anxiety, depression, and, in some cases, post-traumatic stress.

Despite censorship, violence, and mental health struggles, creative artists interviewed for this report say they are resolute and committed to their evolving roles as both leaders and facilitators of the anti-military dictatorship movement. While many believe there is worse yet to come from the military, they also know that the vast majority of the public is behind them, and that their creative expression holds great social and political importance for the future of the country.

Based on the findings in Stolen Freedoms, PEN America puts forward a series of recommendations targeted at Myanmar’s military to end its repression of the people of Myanmar, including the creative community. PEN America also proposes recommendations for foreign governments and intergovernmental bodies, the international creative community, and donors to hold the military accountable for violations of creative expression, while simultaneously strengthening political, financial, and peer support for Myanmar’s creative sector that is adaptable and responsive to the changing situation in the country.

Get out of the Maze

By Ma Thida

No more at the junction of two roads.

No more at the fork in the road.

We are already in the maze.

We know the path is convoluted

but we are determined to walk.

Not missing our goal

like rodents follow

the smell of cheese

without having an experience of

what peace is.

We just follow the scent of blood

rather than curve those passages and

get out of the loop into the dead end

but the path tends towards the sea of blood

no more at the junction of two roads.

We are in the maze.

Flowers might be fallen

but Spring won’t be ruined.

We cry out in the roads

respect our votes

but our roads had been stopped.

Our votes had been chopped.

No more fork in the road.

We are trapped in the maze.

Fight or fright?

Passage to the prison?

Or to the tomb?

We can only choose the right not to fight.

Someone arrested this evening

the next morning the family received his dead body.

Why can we still choose to be frightened?

Many of us who were ambiguous

chose the path of armed struggle.

No more at the junction of two roads.

We are in the maze.

An eye for an eye

would make the whole world blind

but among intellectual blinds

An eye on the walls of a maze

could shoot you till death and

there are many eyes fixed

on this puzzled road.

There will be no branch

without a watching eye.

No more fork in the road.

We are in the built maze.

We still need to reach our goal

though we are forced not to choose the paths anymore.

We can still break down those unicursal walls.

Together we can still make the maze

into an organized space of certain future

with common interests and shared values.

We just need to be aware of

what this maze is, and

how we can turn it inside out.

Let’s get out of this maze

Together.1Ma Thida is a Myanmar human rights activist, surgeon, writer, founding director of PEN Myanmar, and former prisoner of conscience. She is currently Chair of PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee. Ma Thida, “A Poem by Ma Thida,” PEN/Opp, November 5, 2021, penopp.org/articles/poem-ma-thida

Introduction

On October 17, 2021, Kyar Pauk, the lead singer of the rock band Big Bag, auctioned his ukulele, decorated with his own artwork. The payment—$27,500—was donated to Myanmar’s National Unity Government (NUG).2The National Unity Government is a government in exile formed by a group of elected lawmakers and members of parliament ousted by the 2021 coup. “National Unity Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar,” National Unity Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, accessed November 22, 2021, nugmyanmar.org/en; “Who’s Who in Myanmar’s National Unity Government,” The Irrawaddy, April 16, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/whos-myanmars-national-unity-government.html In doing so, Kyar Pauk was risking the increased ire of Myanmar’s military, which had already issued an arrest warrant for him in April for “anti-state activities.”3“Auction for Myanmar Rocker’s Ukulele Breaks World Record,” The Irrawaddy, October 18, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/auction-for-myanmar-rockers-ukulele-breaks-world-record.html

Kyar Pauk is just one of a myriad of Myanmar musicians, singers, painters, sculptors, performance artists, writers, poets, cartoonists, and filmmakers who have used their art to express their hostility to the February 1, 2021 military coup and to support the anti-military dictatorship movement. They join a long line of creative artists who have played historic roles fighting for free and creative expression and independence throughout Myanmar’s tumultuous history.

PEN America’s report Stolen Freedoms: Creative Expression, Historic Resistance, and the Myanmar Coup explores both the considerable chilling effect the coup has had on the public expression of art in the country and—in defiance of this chilling effect—the outstanding outpouring of creative expression since the coup by those who refuse to be silenced. This report also offers a set of recommendations for supporting creative expression in Myanmar now and in the future. As today’s creative artists build upon and draw inspiration from what came before, the report uses a historical frame of reference, juxtaposing current realities with historic creative expression, from British rule and independence, to the nearly five decades of previous military rule, to the recent political opening—the last of which came to a calamitous halt with the military’s antidemocratic and unlawful seizure of power.4Bertil Lintner, “Is There a Way Forward Now for Myanmar?” Global Asia 16, no. 1 (March 2021) globalasia.org/v16no1/focus/is-there-a-way-forward-now-for-myanmar_bertil-lintner The report also places the current Myanmar movement within a wider regional context, linking it to the democracy and solidarity movements across South East Asia and beyond.

This is PEN America’s second report on free and creative expression in Myanmar. The first, Unfinished Freedom: A Blueprint for the Future of Free Expression in Myanmar, was published six years ago, in the wake of the historic parliamentary election landslide that brought Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) to power.5Jane Madlyn McElhone and Karin Deutsch Karlekar, “Unfinished Freedom: A Blueprint for the Future of Free Expression in Myanmar,” PEN America, December 2, 2015, pen.org/research-resources/unfinished-freedom-a-blueprint-for-the-future-of-free-expression-in-myanmar; Jonah Fisher, “Myanmar’s 2015 landmark elections explained,” BBC News, December 3, 2015, bbc.com/news/world-asia-33547036 It was the NLD’s second landslide victory in November 2020 that escalated its political standoff with the military, which the military then used as a guise for carrying out the bloody February 1 coup.6Rebecca Ratcliffe, “UN decries Myanmar ‘catastrophe’ as Aung San Suu Kyi’s trial looms,” The Guardian, June 11, 2021, theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/11/un-decries-myanmar-catastrophe-as-aung-san-suu-kyi-trial-looms

Methodology

The report uses a historical frame of reference, juxtaposing current realities with Myanmar’s rich history of creative expression and artistic resistance, acknowledging the contributions of Myanmar’s past generations of creative artists and their tangible links with the present, and providing a framework by which to understand and analyze current expression and resistance. This juxtaposition of the past and present also sheds light on intergenerational perspectives and contemporary responses to the coup.

The report’s co-authors conducted a desk review of articles, media reports, and books addressing creative expression in Myanmar historically and following the coup, and then worked with two Myanmar consultants and other Myanmar-based partners to conduct qualitative research, including a database of specific cases of repression, a review of the current circumstances of 110 leading creative artists, and in-depth interviews with 21 visual and performance artists, writers, poets, and musicians. The co-authors also consulted expert observers of freedom of expression and Myanmar more broadly. Interviewees provided key examples of creative expression that are highlighted throughout the report.

While it endeavors to be inclusive and representative, a report of this length and nature can not fully capture the scale of creative expression in the post-coup period, or historically. It should therefore be viewed as a snapshot.

The sensitivity of the forms of expression discussed in this report, as well as the fact that many people were working underground or in remote locations with limited communications, presented challenges in terms of research and interviewing. PEN America has taken steps to ensure the security of all those involved, as well as heightened data protection for any information gathered, particularly identifiable private information. Only those individuals who have given PEN America permission to use their names, are playing public roles, and/or have already been publicly identified in the articles referenced in this report, are identified by name. As an additional step to protect interviewees’ identities, PEN America uses “they/them/their” pronouns for all individuals quoted within the report who have requested anonymity.

PEN America has taken care throughout to avoid any direct or indirect recognition of the legitimacy or lawfulness of the military coup. For the sake of clarity, the report places regulatory terms, such as law, in quotation marks whenever there are questions about legitimacy and lawfulness; for example, military-appointed “ministers” and military-adopted “amendments.”

Lastly, a note about the report terminology: PEN America generally uses the term Myanmar to refer to the country or population, except in the historical context section, where the terms Burma/Burmese are used interchangeably for the period prior to 1989, when the military regime changed the name Burma to Myanmar. The word Burmese is also used throughout the report to refer to the language.7J.F. “Should you say Myanmar or Burma?” The Economist, December 20, 2016, economist.com/the-economist-explains/2016/12/20/should-you-say-myanmar-or-burma; The majority of people in Myanmar, referred to as Burman (Bamar), are reported to make up approximately 60% of the population: Simon Roughneen, “Controversy marks start to Myanmar’s first census in three decades,” Los Angeles Times, March 30, 2014, latimes.com/world/la-xpm-2014-mar-30-la-fg-wn-controversy-marks-start-to-myanmars-first-census-in-three-decades-20140330-story.html The term “creative artist” is used throughout the report to refer to individuals engaged in creative expression, including literary writers, poets, visual artists, filmmakers, and singer/songwriters.

Myanmar’s long history of creative expression

It is challenging, if not impossible, to capture the breathtaking scale of Myanmar’s long history of creative expression in a single report. Traditional art forms, known by the public as the “10 flowers” (pan sè myo), include metalwork, sculpture, and paintings, and can be traced back over a thousand years with close links to the development of Buddhism and Hinduism.8The others being goldsmithing, bronze-casting, floral motifs from stone, masonry, lathe-work, and lacquerware: “10 Myanmar Traditional Arts,” Myanmar Travel Information, accessed January 4, 2010, web.archive.org/web/20100104230600/myanmartravelinformation.com/mti-myanmar-arts/index.htm A comparatively long history of public literacy, driven by the desire to read Buddhist verse, enabled literature to flourish earlier than elsewhere in the region.9Juliane Schober, “Colonial Knowledge and Buddhist Education in Burma,” in Buddhism, Power and Political Order (London: Routledge, 2007), 57, academia.edu/879830/Colonial_Knowledge_and_Buddhist_Education_in_Burma Poetry has also played an important role for hundreds of years, including in the royal dynasty courts and in the resistance to the British.10“Why So Many Poets were Elected to Parliament in Myanmar,” Coconuts Yangon, December 4, 2015, coconuts.co/yangon/lifestyle/why-so-many-poets-were-elected-parliament-myanmar/ In 1873, when Lower Burma11J.F. “Should you say Myanmar or Burma?” The Economist, December 20, 2016, economist.com/the-economist-explains/2016/12/20/should-you-say-myanmar-or-burma was under British control and repressive laws constrained media and free expression, Upper Burma’s monarch, King Mindon, passed “Southeast Asia’s first indigenous press freedom law.”12“Chronology of the Press in Burma,” The Irrawaddy, May 2004, irrawaddy.com/article.php?art_id=3533&page=2 In 1906, Burma’s illustrious film industry got its start in the streets, with film projected onto large cotton sheets supported by scaffolding. The first Burmese feature film followed in 1920, as did documentaries of student and independence leader funerals, and the country’s longest civil war in Karen (Kayin) State.13Aung Min, “The Story of Myanmar Documentary Film,” The Guggenheim Museums and Foundation, December 11, 2012, guggenheim.org/blogs/map/the-story-of-myanmar-documentary-film; Zon Pann Pwint, “Family of studio founder to mark 90 years of movies,” Myanmar Times, January 23, 2012, mmtimes.com/lifestyle/1318-family-of-studio-founder-to-mark-90-years-of-movies.html

Fight for independence

By the early 1900s, creative expression became more politically engaged, subversive, and revolutionary. Following World War I, the nationalist poet U Maung Lun—whose pen name “Mr. Maung Hmaing” poked fun at Burmese who adopted English affectations such as putting “Mr.” before their name—called on Burmese to resist foreign influence and power.14“Thakin Kodaw Hmaing,” The Irrawaddy, March 2000, irrawaddy.com/article.php?art_id=1836 Promoting national pride, the independence movement adopted songs such as ‘Nagani’ (Red Dragon).15Aung Zaw, “Burma: Music under siege,” in Shoot the Singer!: Music Censorship Today, Volume 1 (London: Zed Books, 2004), 39, freemuse.org/news/myanmarburma-music-under-siege/ In 1915, a British railway official drew the first cartoon published in the country;16Tin Htet Paing, “Burmese Cartoons Celebrate Centenary in Rangoon,” The Irrawaddy, December 31, 2015, https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/burmese-cartoons-celebrate-centenary-in-rangoon.html shortly after, a 1917 cartoon by Shwe Ta Lay—critiquing British officials for wearing shoes in Buddhist pagodas—contributed to the rise in Burmese nationalism and demonstrated the power of political artwork.17Aung Zaw, “Pioneers of Burmese Cartooning,” The Irrawaddy, March 2, 2020, irrawaddy.com/from-the-archive/pioneers-burmese-cartooning.html; Jennifer Leehey, “Message in a Bottle: A Gallery of Social/Political Cartoons from Burma,” Asian Journal of Social Science 25, no. 1 (January 1997): 152, deepdyve.com/lp/brill/message-in-a-bottle-a-gallery-of-social-political-cartoons-from-burma-WmegN1ausH In the 1930s, the Khitsan poetry movement got its start at Rangoon (now Yangon) University and contributed to the independence struggle during British rule.”18Maung Day, “A brief introduction to the poetry of Burma,” British Council, November 7, 2016, britishcouncil.org/voices-magazine/brief-introduction-poetry-burma; “Why So Many Poets were Elected to Parliament in Myanmar,” Coconuts Yangon, December 4, 2015, coconuts.co/yangon/lifestyle/why-so-many-poets-were-elected-parliament-myanmar According to Burmese writer and poet Maung Day, “Khitsan is sometimes translated as ‘testing the times’ and sometimes as ‘renewal of times.’”19Maung Day, “A brief introduction to the poetry of Burma,” British Council, November 7, 2016, britishcouncil.org/voices-magazine/brief-introduction-poetry-burma

In 1947, months before the country’s formal independence, Burma’s first constitution guaranteed a right to freely express opinions and convictions. Writers, poets, painters, visual artists, musicians, cartoonists, and filmmakers experienced a brief, heady period of free and creative expression, with few restrictions and little harassment.20Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 17 Following independence, the Burmese press was considered one of the freest in Asia.21Aung Zaw, “Burma: Music under siege,” in Shoot the Singer!: Music Censorship Today, Volume 1 (London: Zed Books, 2004), 40, freemuse.org/news/myanmarburma-music-under-siege/ Yet as time passed, these freedoms were gradually curtailed by the government, and literary criticism and other forms of writing became increasingly politicized.22Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 17 In 1948, U Nu became the first democratically elected prime minister in Burma; in his memoirs, he revealed that he had really longed to be a playwright.23“Why So Many Poets were Elected to Parliament in Myanmar,” Coconuts Yangon, December 4, 2015, coconuts.co/yangon/lifestyle/why-so-many-poets-were-elected-parliament-myanmar

1962 coup

In 1962, when General Ne Win seized power in a military coup—the start of close to five decades of military dictatorship and censorship—free and creative expression suffered a deadly blow.24Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 18 By 1964, private publications were shut and editors and journalists arrested. While documentary filmmaking was largely used for propaganda, political cartooning provided critique and political commentary. Feature films continued to be produced and screened in cinemas across the country, yet by 1968 cinemas and production houses were nationalized, leading to a sectoral decline. Ne Win also sought to use music to serve his political agenda, appropriating songs and musicians and banning western music and dancing; yet given the rising popularity of rock and pop music in the early ’60s, there was resistance, especially from the younger generations. An underground music culture called “stereo” music emerged, with music secretly recorded and distributed.25Aung Zaw, “Burma: Music under siege,” in Shoot the Singer!: Music Censorship Today, Volume 1 (London: Zed Books, 2004), 40-42, freemuse.org/news/myanmarburma-music-under-siege/ Much of book publishing remained private, yet it was subject to the Press Scrutiny Board’s pre-publication approval. Censorship boards were also created for film, video, music, paintings, and book covers. In the 1970s and 1980s, monthly literary magazines became a prominent platform for writing, literature, and literary debate.26Jennifer Leehey, “Writing in a Crazy Way: Literary Life in Contemporary Urban Burma,” in Burma at the Turn of the 21st Century, ed. Monique Skidmore (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2005), 175–205 A new style of Burmese literature also emerged, “characterized by shifting and elusive meaning, which through its very shifting . . . captures something important about the subjective experience of everyday life under military rule.”27Jennifer Leehey, “Writing in a Crazy Way: Literary Life in Contemporary Urban Burma,” in Burma at the Turn of the 21st Century, ed. Monique Skidmore (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2005), 175–205 Meanwhile, writers and poets, who continued to meet in tea shops to discreetly discuss their works, were targeted and blacklisted.

In 1974, a new constitution granted freedom of speech, expression, and publication in line with the so-called “Burmese Way to Socialism”; publishers were forced to submit printed copies of their publications which were then censored, either by having pages ripped out or sections blacked out. Writers and poets adopted pen names and abstract, coded language. The line between poetry and activism blurred, and hundreds of writers and poets became political prisoners.28“Why So Many Poets were Elected to Parliament in Myanmar,” Coconuts Yangon, December 4, 2015, coconuts.co/yangon/lifestyle/why-so-many-poets-were-elected-parliament-myanmar

1988 coup and student uprising

In 1988, General Ne Win embarked on his 26th year of repressive and violent power. Burma was isolated and one of the poorest countries in the world.29Jonathan Head, “Myanmar coup: What protesters can learn from the ‘1988 generation,’” BBC News, March 16, 2021, bbc.com/news/world-asia-56331307 In the wake of the regime’s decision to devalue the local currency, thereby wiping out many people’s savings, students began organizing protests. In July, Ne Win resigned as head of the Burma Socialist Program Party, promising to create a multi-party system, yet also threatening student protesters.30“Timeline: Myanmar’s ‘8/8/88’ Uprising,” WNYC, August 8, 2013, npr.org/2013/08/08/210233784/timeline-myanmars-8-8-88-uprising The announcement that the man responsible for the violent repression of student protests, Sein Lwin, was his successor provoked a countrywide general strike. Although Sein Lwin also subsequently resigned, the protests continued to grow. Aung San Suu Kyi made her first public speech and soon after launched her party, the National League for Democracy. On September 18, a new leader, Saw Maung, and a new party, the State Law and Order Restoration Committee (SLORC), seized power in a coup that restored martial law.31Jonathan Head, “Myanmar coup: What protesters can learn from the ‘1988 generation,’ ” BBC News, March 16, 2021, bbc.com/news/world-asia-56331307; “Timeline: Myanmar’s ‘8/8/88’ Uprising,” WNYC, August 8, 2013, npr.org/2013/08/08/210233784/timeline-myanmars-8-8-88-uprising

The 1988 student uprising is considered a key moment in Myanmar’s history. The “88 Generation of Students” who led the uprising—many of whom spent decades in prison—are held in high esteem. An estimated 3,000 people were killed and 3,000 more imprisoned. Ten thousand people fled the country, including many students, journalists, cartoonists, writers, and other artists, some to ethnic minority-controlled areas along the borderlands, and others into exile.32Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 21 The famous Burmese comedian and satirist Maung Thura, well-known by his stage name Zarganar, was arrested for participating in the pro-democracy movement and imprisoned until April 1990.33Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 22 Another satirist, writer, and supporter of Aung San Suu Kyi, Maung Thawka, was elected president of the unofficial Union of Burmese Writers in 1988. When Aung San Suu Kyi was placed under house arrest in 1989, Maung Thawka was also arrested and died in prison two years later.34Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 22

In 1989, the SLORC amended the 1962 Printers and Publishers Registration Act, outlawing “sensitive” topics and increasing fines for violations.35Examples included democracy, human rights, politics, the 1988 uprising, government officials, opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi, and South African freedom fighter Nelson Mandela. Ibid, p.22 Leading writers, such as the chairman and vice-chairman of the Myanmar Writers Association, Ba Thaw and Win Tin, were arrested. Escalating production costs and censorship obstructed publishing. Ethnic minority writers and intellectuals were arrested or went underground, and fewer books were published in their minority languages. In 1989, the Ministry of Home and Religious Affairs established a new censorship board, ostensibly to “protect” Burmese music from so-called foreign influences, and to “warn” musicians to be “patriotic and cooperate” with the state-controlled Myanmar Media Association.36Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 23 The film and video industry was targeted, with actors and directors arrested, the chairman of the Burma Film Society charged with treason, and actors and directors pressured to work with the official Motion Picture Organization. Following a performance at the NLD headquarters during the 1989 Thingyan New Year water festival, musicians and singers were also arrested. In May 1990, one month after being released from prison, Zarganar was rearrested after performing stand-up comedy about the Minister of Information at the Yankin Teachers Training College Stadium in Yangon.37“Zarganar: Myanmar,” PEN America, accessed November 22, 2021, pen.org/advocacy-case/zarganar Sentenced to five years imprisonment but released in March 1994, he was banned from using his stage name and from performing publicly or attending public events. Despite these sanctions, the military often invited him to appear on military television. He declined their invitations.38Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 23

Writers and journalists who fled the country in 1988 to the protected borderlands published magazines that featured young writers and cartoonists. Private monthly magazines re-emerged inside the country in the 1990s. Short stories were considered a popular and important literary genre, in great part due to their use of metaphors, allusion, and irony.39Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 24-25 Yet since all printed publications had to be submitted to the Press Scrutiny Board, there was pressure to self-censor. Prior to computers, censorship largely happened after printing but before distribution, so physical changes would need to be made to the printed copies or they would have to be scrapped at significant cost. Then, with the introduction of computers in the 1990s, pre-print censorship was introduced.40Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 24–25

During this time, documentary filmmaking was still nascent inside the country, yet under the tutelage of the the Yangon Film School (YFS) and the Alliance Française in the mid-2000s, a new generation of Burmese filmmakers emerged on the scene. Local punk and hip-hop bands also emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The anti-establishment punk rock songs performed by local bands such as No U-Turn and Side Effect became famous. The first Burmese hip-hop group, ACID, was founded in 2000 by Phyo Zayar Thaw and three of his fellow musicians, Annaga, Hein Zaw, and Yan Yan Chan. Band members had to submit their lyrics, demo tapes, recordings, and artwork to censors, and risked being targeted by authorities and arrested if they were deemed to promote democracy and social justice.41Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 27

Saffron Revolution and Cyclone Nargis

In September 2007—in what became known as the Saffron Revolution—thousands of students, including prominent leaders of the ’88 Generation, monks, and other people of Myanmar participated in massive demonstrations across the country, calling for an end to military rule and for democracy.42“Saffron Revolution in Burma,” Burma Campaign UK for Human Rights, Democracy & Development in Burma, accessed November 22, 2021, burmacampaign.org.uk/about-burma/2007-uprising-in-burma The military regime arrested thousands of people, including many of the protest leaders. Despite the risks and strict media censorship, Myanmar activists found ways to post photographs and videos of the demonstrations online until the military shut off the internet.43“Saffron Revolution in Burma,” Burma Campaign UK for Human Rights, Democracy & Development in Burma, accessed November 22, 2021, burmacampaign.org.uk/about-burma/2007-uprising-in-burma Inspired by the Saffron Revolution protests, popular hip-hop artist Phyo Zayar Thaw co-founded the youth activist group, Generation Wave, using creative expression, including hip-hop and graffiti, to advocate for democracy. On March 12, 2008, he was sentenced to six years in prison for participating in anti-regime protests; five other members of Generation Wave received five-year sentences. Phyo Zayar Thaw later became an NLD MP.44Min Lwin, “Hip-Hop Performer among Latest Victims of Court Crackdown,” The Irrawaddy, November 20, 2008, globaljusticecenter.net/files/Article.HipHopPerformeramongLatestVictimsCourtCrackdown.TheIrrawaddy.Nov.2008.pdf; Namoi Gingold, “Generation Wave Celebrates 6th Anniversary,” The Irrawaddy, October 10, 2013, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/generation-wave-celebrates-6th-anniversary.html; “Junta arrests former NLD legislator accused of leading attacks on regime targets,” Myanmar Now, November 19, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/junta-arrests-former-nld-legislator-accused-of-leading-attacks-on-regime-targets Known for their satirical skits and jokes aimed at the military, the acclaimed a-nyeint comedy troupe, Thee Lay Thee & Say Yaung Zona, was asked to sign a document saying they would not make jokes on stage,45A-nyeint is a traditional form of theater performed in Myanmar that includes music, songs, dance and comedy; Myanmar Celebrity, “ဗိုလ်ချုပ် မွေးနေ့ နှစ် (၁၀၀) ပြည့်မှာ ဖျော်ဖြေခဲ့တဲ့ နှင်းဆီ အဖွဲ့ အပိုင်း (၂),” YouTube, February 12, 2015, youtube.com/watch?v=0d170zhm5sU but at a performance in Yangon in the wake of the protests, their jokes attacked the military’s crackdown on protesters. Although the recording of that performance was officially banned, it reached a huge audience outside of the country, as well as inside via VCDs (video CDs) that were circulated underground.46“From Rock to Romance,” The Irrawaddy, December 2008, irrawaddy.com/article.php?art_id=14749

One year later, in 2008, artists organized fundraising activities for the victims of the devastating Cyclone Nargis, during which 50,000 people—reportedly the largest concert audience the country had seen to that point—attended a benefit concert by the Myanmar band Iron Cross at the Thuwanah Sports Stadium in Yangon.47“From Rock to Romance,” The Irrawaddy, December 2008, irrawaddy.com/article.php?art_id=14749 While some artist associations were allowed to fundraise, others were banned, including the Mandalay pro-democracy comedy troupe, Moustache Brothers.48Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 30

Political opening

Myanmar’s political transition brought with it positive change for the creative sector. In December 2011, Kyaw San, the Minister of Information and the Minister of Culture, announced that film and video censorship would be eased; as a result, for the first time Burmese could openly attend screenings of Burma VJ, the story of the video journalists who covered the Saffron Revolution; and Nargis, about the victims of Cyclone Nargis.49Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 38 The abolition of pre-publication press censorship in 2012 also had a positive impact on the media and publishing sector, sparking a surge of new publications, including about the creative arts. In February 2013, Myanmar hosted its first international literary festival.50Brooten, McElhone, and Venkiteswaran, “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition,” in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 38 One month later, at The Art of Transition Symposium in Yangon, artists and writers gathered to discuss creative expression and the impact of the recent political reforms.51Julia Farrington, “Burma: The art of transition,” Index on Censorship, February 24, 2014, indexoncensorship.org/2014/02/burma-the-art-of-transition/

On November 8, 2015, 11 poets who were members of the National League for Democracy, led by Aung San Suu Kyi, were elected to Myanmar’s national and regional parliaments,52“Why So Many Poets were Elected to Parliament in Myanmar,” Coconuts Yangon, December 4, 2015, coconuts.co/yangon/lifestyle/why-so-many-poets-were-elected-parliament-myanmar/ including PEN/Freedom to Write Award recipient Nay Phone Latt, who explained in an interview, “Some of the people said that we already have freedom of expression, but it’s not totally true. Compared to the military, we have some, but the freedom we have is state-limited. They still have the boundary. If you go over the boundary and limitation, everybody can get into trouble. So, we still need to fight for freedom of expression. That is why I think some writers, authors, and poets joined the parliament.”53“Why So Many Poets were Elected to Parliament in Myanmar,” Coconuts Yangon, December 4, 2015, coconuts.co/yangon/lifestyle/why-so-many-poets-were-elected-parliament-myanmar; elected MP for Yangon Region, Nay Phone Latt was also co-founder of PEN Myanmar and Myanmar IT for Development Organization

Myanmar poets have often been associated with political activism. As writer and poet Maung Day said in 2016, “The president himself [Htin Kyaw54Poppy McPherson and Aung Naing Soe, “Htin Kyaw: who is Myanmar’s new president?” The Guardian, March 15, 2016, theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/10/htin-kyaw-myanmar-president-electon-aung-san-suu-kyi-nld] is the son of a poet, and known for his literary inclinations. However, poetry transcends politics. Most Burmese people grow up reading poetry from kindergarten until university . . . Today, the poetry scene in Burma is thriving. Poets write in various styles and traditions, from khitpor (modern), which emerged in the 1970s, to conceptual forms including Flarf and visual poetry. As the country opens up, the outside world has become curious about Myanmar arts and culture. Young Myanmar poets are writing experimental poetry about social justice issues, and collaborating with artists and writers from other countries.”55Maung Day, “A brief introduction to the poetry of Burma,” British Council, November 7, 2016, britishcouncil.org/voices-magazine/brief-introduction-poetry-burma. Parentheses original. Flarf is a post-modern poetic form.

While the partial relaxation of censorship for creative works did create a new openness and a freer space for previously banned music, comedy, and traditional forms of satirical critique, bureaucracy and a restrictive legal framework continued to create hurdles that were at times insurmountable. Live music performances, for example, continued to require advance permits, a process that was blatantly wielded by the authorities to control musicians and their music. Performance art, live music, and live theater were always under threat from the vague Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law, which contained several provisions that could be used to arbitrarily close down events and criminalize organizers.56Brooten, McElhone and Venkiteswaran (2019), “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition”, in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 38–39 The film censorship board prevented politically sensitive films on issues of conflict and human rights violations from being screened,57“Maintaining a Reality? – Structures of Censorship in Myanmar,” Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, July 2, 2018, myanmar.fes.de/e/maintaining-a-reality-structures-of-censorship-in-myanmar/ while allowing others with violent, nationalistic, and discriminatory undertones.58Aung Kaung Myat, “Military Rule May Be Over, But Myanmar’s Film Industry Remains in a Tawdry Time Warp,” Time, August 22, 2018, time.com/5374231/myanmar-cinema-film-movies/ In 2016, after the NLD came to power, the film censorship board also blocked the film Twilight over Burma59“Twilight over Burma,” IMDb, accessed November 22, 2021, imdb.com/title/tt4265880/from being screened at the annual Myanmar Human Rights Human Dignity International Film Festival, despite the fact that Aung San Suu Kyi was the film festival patron.60Brooten, McElhone and Venkiteswaran (2019), “Myanmar Media Historically and the Challenges of Transition”, in Myanmar Media in Transition: Legacies, Challenges and Change (Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2019), 38; “About Us,” Human Rights Human Dignity International Film Festival, accessed November 23, 2021, hrhdiff.netscriper.biz/about-us/ These regressions were in line with other rollbacks on free and creative expression and media freedom under the NLD.61“Scorecard Assessing Freedom of Expression in Myanmar,” PEN Myanmar Center, May 2, 2018, pen-international.org/app/uploads/2018-Scorecard-ENG.pdf

Creative artists often fell afoul of Myanmar’s myriad laws criminalizing expression, which were wielded against journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens for their online speech.62The range of repressive laws used to restrict and punish free expression are summarized in the following reports: Jane Madlyn McElhone and Karin Deutsch Karlekar, “Unfinished Freedom: A Blueprint for the Future of Free Expression in Myanmar,” PEN America, December 2, 2015, pen.org/research-resources/unfinished-freedom-a-blueprint-for-the-future-of-free-expression-in-myanmar; Linda Lakhdhir, “Dashed Hopes: The Criminalization of Peaceful Expression in Myanmar,” Human Rights Watch, January 31, 2019, hrw.org/report/2019/02/01/dashed-hopes/criminalization-peaceful-expression-myanmar These included the multiple criminal provisions in the Penal Code on defamation, sedition, incitement, and unlawful assembly. Threatening criminal laws also included the defamation provisions in the Telecommunications Law, which was regularly used to suppress dissent online.

On November 5, 2015, after publishing a poem on Facebook intimating he had a tattoo of the president on his penis, Maung Saungkha was arrested and accused of defaming Thein Sein, then president, under Section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Law. On May 24, 2016, he was found guilty and sentenced to six months in prison, yet since he had already been detained for more than six months, he was released. Maung Saungkha was one of the first writers to be convicted and sentenced following the historic 2015 elections, and under Section 66(d) of the Telecommunications Law.63“Myanmar: Poet Maung Saugkha Released,” PEN America, May 24, 2016, pen.org/press-release/myanmar-poet-maung-saungkha-released/ He later was one of the co-founders of the civil society organization, Athan: Free Expression Activist Organization.64“About,” Athan, accessed November 22, 2021, athanmyanmar.org/about/

On April 12, 2019, award-winning filmmaker Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi was detained and later sentenced in August to one year’s imprisonment in Yangon’s notorious Insein Prison. His crime: criticizing the military in his social media posts. Ko Ko Gyi was convicted under Section 505(a) of the Penal Code; 505(a) criminalizes making, publishing, or sharing “any statement, rumor or report” that encourages a member of the military “to mutiny or otherwise disregard or fail in his duty.”65Charlotte Soehner, “Artist Profile: Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi,” Artists at Risk Connection, accessed November 22, 2021, artistsatriskconnection.org/story/min-htin-ko-ko-gyi As if the prison term alone was not vindictive enough, the military sought a sentence of hard labor knowing that Ko Ko Gyi was suffering from serious illness. On February 21, 2020, Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi was released from Insein Prison; the remaining charges against him under Section 66(d) were dropped. As soon as he was released, he called for changes to the Penal Code.66Charlotte Soehner, “Artist Profile: Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi,” Artists at Risk Connection, accessed November 22, 2021, artistsatriskconnection.org/story/min-htin-ko-ko-gyi

In October 2019, the military brought a case against poet Saw Wai for remarks he made at a political rally, and a court accepted the alleged military defamation charge under section 505(a).67“Saw Wai,” PEN America, accessed November 23, 2021, pen.org/advocacy-case/saw-wai/ In an unusual occurrence under section 505(a), Saw Wai was ultimately granted bail due to his age and compromised health, though the case continued.68Zaw Zaw Htwe, “Myanmar Court Grants Bail to Lawyer and Poet Sued by Military,” The Irrawaddy, February 3, 2020, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-court-grants-bail-lawyer-poet-sued-military.html Also in October, five performance artists from the group Peacock Generation were sentenced to imprisonment for “incitement to mutiny” after performing thangyat, a form of slam poetry.69The peacock is the symbol of Aung San Suu Kyi’s political party, the National League for Democracy. The charges were laid under Penal Code 505(a) which relates to inciting mutiny: “Myanmar: Satire performers who mocked military face prison in ‘appalling’ conviction,” Amnesty International, October 30, 2019, amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2019/10/myanmar-satire-performers-who-mocked-military-face-prison-appalling-conviction; “PEN America Condemns Sentencing of Five Myanmar Actors,” PEN America, October 31, 2019, pen.org/press-release/pen-america-condemns-sentencing-of-five-myanmar-actors/ Kay Khine Tun, Zayar Lwin, Paing Pyo Min, Paing Ye Thu, and Zaw Lin Htut were dressed in military fatigues and their chants mocked the authorities. The group faced a barrage of legal harassment for their performances. As they had performed in different locations, the authorities brought the same incitement charges under Penal Code Section 505(a) against them in multiple townships simultaneously.70Leila Sadat, “The Trial of the Peacock Generation Trope: Myanmar,” Clooney Foundation for Justice’s TrialWatch Initiative, August 2020, cfj.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Fairness-Report-on-the-Trial-of-the-Peacock-Troupe.pdf They were also charged and sentenced for online defamation after live-streaming the performance on Facebook.71“Myanmar: New convictions for ‘Peacock Generation’ members,” Amnesty International UK, May 18, 2020, amnesty.org.uk/resources/myanmar-new-convictions-peacock-generation-members Each charge added consecutive prison terms to their sentences, and they were only all released in April 2021, just before their parole date.72“Myanmar: More ‘outrageous’ convictions for satire performers,” Amnesty International, February 17, 2020, amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/02/myanmar-more-outrageous-convictions-for-satire-performers; “Nine activists among more than 23,000 freed as part of Thingyan amnesty,” Myanmar Now, April 17, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/nine-activists-among-more-than-23000-freed-as-part-of-thingyan-amnesty; During the same week, four other members of the group were detained on their way to an anti-coup protest

On a positive note, during this period some popular punk bands, including Side Effect, used their performances and influence to campaign against hate speech and persecution of the Rohingya, while others used hip-hop and other art forms to raise general political awareness among young people.73Hanna Hindstrom, “Myanmar’s punk rockers challenge anti-Muslim rhetoric,” Al Jazeera, November 3, 2015, aljazeera.com/features/2015/11/3/myanmars-punk-rockers-challenge-anti-muslim-rhetoric According to Side Effect’s lead singer Darko, his visits with Rohingya living in northern Rakhine State opened his eyes to their plight,74Bill Frelick, “‘Bangladesh Is Not My Country’: The Plight of Rohingya Refugees from Myanmar,” Human Rights Watch, August 5, 2018, hrw.org/report/2018/08/05/bangladesh-not-my-country/plight-rohingya-refugees-myanmar and the dangers of entrenched racism and hate speech.75Hanna Hindstrom, “Myanmar’s punk rockers challenge anti-Muslim rhetoric,” Al Jazeera, November 3, 2015, aljazeera.com/features/2015/11/3/myanmars-punk-rockers-challenge-anti-muslim-rhetoric Darko’s band also collaborated with the NGO Turning Tables on the song “Wake Up Myanmar,” which called for an end to military dictatorship and oppressive laws.76Hanna Hindstrom, “Myanmar’s punk rockers challenge anti-Muslim rhetoric,” Al Jazeera, November 3, 2015, aljazeera.com/features/2015/11/3/myanmars-punk-rockers-challenge-anti-muslim-rhetoric Another punk group, Rebel Riot, emerged in the wake of the 2007 Saffron Revolution; as a result of its 2013 songs, such as “Stop Racism” and “Fuck Religious Rules,” the band received online threats.77Hanna Hindstrom, “Myanmar’s punk rockers challenge anti-Muslim rhetoric,” Al Jazeera, November 3, 2015, aljazeera.com/features/2015/11/3/myanmars-punk-rockers-challenge-anti-muslim-rhetoric; The Rebel Riot, Fuck Religious Rules/Wars, Self release, 2014, Digital Media, therebelriot.bandcamp.com/album/fuck-religious-rules-wars

Compared to the previous period of repressive military rule, the political opening—during which Myanmar was governed by the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) administration from 2010–2015, followed by the NLD’s first administration from 2016–2021—was marked by greater freedoms for creative artists and writers. When the NLD assumed power in 2016, expectations were particularly high. Yet despite calls from civil society, including free and creative expression advocates, the NLD failed to implement reforms, repressive legal structures remained largely intact, and criminal laws were used repeatedly to punish individuals for their creative expression and to chill free speech.78See for example, Free Expression Myanmar’s five year review of free speech reforms under the NLD, submitted to the UN’s Universal Periodic Review in 2020: “Reform abandoned?: 5-year review of freedom of expression for Myanmar’s 2020 UN Universal Periodic Review,” Free Expression Myanmar, accessed November 22, 2021, freeexpressionmyanmar.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/reform-abandoned.pdf; See also, for example, a package of case infographics produced by Athan on the NLD’s four years of reform for the 2020 World Press Freedom Day: “Analysis on Freedom of Expression Situation in Four Years under the Current Regime,” Athan, May 2, 2020, drive.google.com/file/d/1Suz4sCtyoiV6-W91rm7Bt_ZWMRszkTU1/view?usp=sharing As a participant in PEN Myanmar’s 2018 Scorecard Assessing Freedom of Expression in Myanmar noted, “People who freely express their opinions in this country are not safe.”79“Scorecard Assessing Freedom of Expression in Myanmar,” PEN Myanmar, May 2, 2018, p.5, pen-international.org/app/uploads/2018-Scorecard-ENG.pdf The legacy of the NLD’s first term in office was thus a deteriorating environment with regard to free and creative expression and media freedoms.

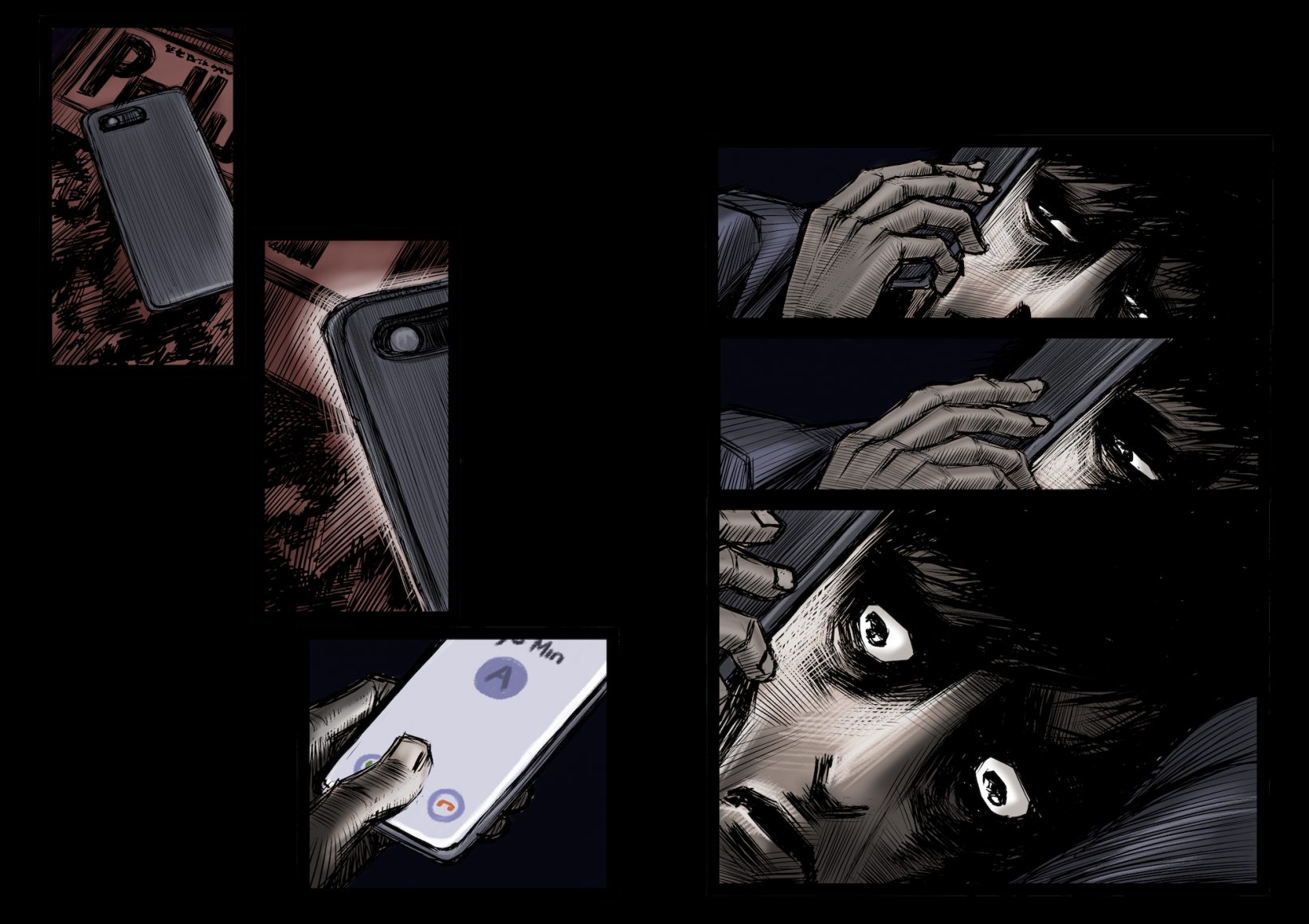

Creative expression and the 2021 coup

At 3am (Myanmar local time) on February 1, 2021, a small internet monitoring organization in the U.K. began seeing minor disruptions to internet infrastructure in Myanmar.80“Internet disrupted in Myanmar amid apparent military uprising,” NetBlocks, January 31, 2021, netblocks.org/reports/internet-disrupted-in-myanmar-amid-apparent-military-uprising-JBZrmlB6 A few hours later, phone lines to Myanmar’s capital city, Naypyidaw, were cut and state television channels were taken off the air.81“Aung San Suu Kyi and other leaders arrested, party spokesman says,” Reuters, February 1, 2021, trust.org/item/20210131230656-kkg7f Under the cover of darkness, the military raided the homes of senior politicians, detaining President Win Myint and Myanmar’s de facto leader, State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi.82“Aung San Suu Kyi and other leaders arrested, party spokesman says,” Reuters, February 1, 2021, trust.org/item/20210131230656-kkg7f Shortly after, the military seized parliament—a move that was inadvertently livestreamed on Facebook by fitness instructor Khing Hnin Wai.83Helen Sullivan, “Exercise instructor appears to unwittingly capture Myanmar coup in dance video,” The Guardian, February 1, 2021, theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/02/exercise-instructor-appears-to-unwittingly-capture-myanmar-coup-in-dance-video

Over the next few days, information trickled out that the military, under the leadership of General Min Aung Hlaing, had placed 400 members of parliament under house arrest, and detained 147 people, mostly senior NLD officials, as well as 14 civil society leaders, 3 monks, and 5 creative artists who were all well-known supporters of the NLD. These five artists included filmmaker Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi, singer Saw Phoe Khwar, and writers Maung Thar Cho, Than Myint Aung, and Htin Lin Oo.84“Hundreds of Myanmar MPs under house arrest,” The News International, February 3, 2021, thenews.com.pk/print/784319-hundreds-of-myanmar-mps-under-house-arrest; “Recent Arrest List Last Updated Feb 4,” Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, February 4, 2021, aappb.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Recent-Arrest-List-Last-Updated-on-Feb-4.pdf; “Statement on Recent Detainees in Relation to the Military Coup,” Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, February 4, 2021, aappb.org/?p=12997; “Three Saffron Revolution monks among those detained in February 1 raids,” Myanmar Now, February 3, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/three-saffron-revolution-monks-among-those-detained-in-february-1-raids; “Recent Arrest List CSOs Last Updated Feb 4,” Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, February 4, 2021, aappb.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Recent-Arrest-List-CSOsLast-Updated-on-Feb-4.pdf

The military attempted to justify its power grab with the pretext that it had seized power due to a failure of the NLD administration to address what the military claimed were “widespread irregularities on the voter list,” a claim that is without any merit.85Victoria Milko, “EXPLAINER: Why did the military stage a coup in Myanmar?” AP News, February 2, 2021, apnews.com/article/military-coup-myanmar-explained-f3e8a294e63e00509ea2865b6e5c342d Some observers believe that the military was hoping to follow in the path of other global leaders trumpeting election fraud without evidence.86Hayes Brown, “Myanmar’s military, like Trump, cited fake ‘election fraud’ claims to justify a coup,” MSNBC, February 1, 2021, msnbc.com/opinion/myanmar-s-military-trump-cited-fake-election-fraud-claims-justify-n1256401; Jonah Shepp, “Myanmar’s Military Pulled Off the Coup Trump Couldn’t,” New York Magazine, February 2, 2021, nymag.com/intelligencer/article/myanmar-military-coup-trump.html Just three months earlier, the NLD, led by Aung San Suu Kyi, had won a second landslide victory with an increased share of the general election vote, trouncing the opposing military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), which lost many of its parliamentary seats.87Zsombor Peter, “Aung San Suu Kyi, NLD Win Second Landslide Election in Myanmar,” VOA News, November 15, 2020, voanews.com/a/east-asia-pacific_aung-san-suu-kyi-nld-win-second-landslide-election-myanmar/6198393.html Observers have also pointed to coup leader General Min Aung Hlaing’s failed political ambitions and fears of prosecution for crimes against humanity for his role in the persecution of the Rohingya as motivations for the coup.88“Myanmar coup: Min Aung Hlaing, the general who seized power,” BBC News, February 1, 2021, bbc.com/news/world-asia-55892489 The military’s initial statement that it would hold fresh elections within a year has subsequently been replaced by a promise to hold them within three years.89“Myanmar to clarify voter fraud, hold new round of elections,” Myanmar Times, February 1, 2021, mmtimes.com/news/myanmar-clarify-voter-fraud-hold-new-round-elections.html

Unrule of law

Since February 1, the Myanmar military has steadfastly denied that it carried out a coup d’état, instead claiming without evidence that detained President Win Myint resigned, and that his replacement called a state of emergency and transferred executive, legislative, and judicial authority to the military’s commander-in-chief, general Min Aung Hlaing.90Kang Wan Chern, “Myanmar announces state of emergency,” February 1, 2021, mmtimes.com/news/myanmar-announces-state-emergency.html; See also, discussion on the merits of the claim by academics: Melissa Crouch, The Constitution of Myanmar, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019, bloomsbury.com/uk/constitution-of-myanmar-9781509927371/; and by CSOs: “Statement by Myanmar civil society organisations on the unconstitutionality of new ‘laws,’” Free Expression Myanmar, February 19, 2021, freeexpressionmyanmar.org/statement-by-myanmar-civil-society-organisations-on-the-unconstitutionality-of-new-laws/; Victoria Milko, “EXPLAINER: Why did the military stage a coup in Myanmar?” AP News, February 2, 2021, apnews.com/article/military-coup-myanmar-explained-f3e8a294e63e00509ea2865b6e5c342d The military’s published declaration of a state of emergency omits details about the temporary suspension of citizens’ rights, so it is unclear whether the constitutional protections for free and creative expression, namely the rights to freedom of expression, freedom of association, and freedom to develop literature and the arts, still apply in principle.91Article 414(b) of the Constitution, see “Statement from Myanmar military on state of emergency,” Reuters, January 31, 2021, reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-politics-military-text-idUSKBN2A11A2; Articles 354(a), 354(c), and 365 of the Myanmar Constitution It also omits details on whether broader constitutional rights relating to the rule of law have been suspended.

Immediately after seizing parliament, the military began stripping away judicial independence, ensuring its control over all three pillars of the state. The military suspended the supreme court’s power to enforce constitutional rights through the issuing of writs, and then replaced the majority of the judges who had been installed under the NLD with individuals from the military’s secretive tribunals.92Melissa Crouch, “The coup and the capture of the courts,” February 9, 2021, melissacrouch.com/2021/02/09/the-coup-and-the-capture-of-the-courts/; “Duty Termination from Justices of Supreme Court of the Union,” The Global New Light of Myanmar, February 5, 2021, gnlm.com.mm/duty-termination-from-justices-of-supreme-court-of-the-union/ It also preempted any claims on the legality of its coup d’état by appointing nine new members to Myanmar’s Constitutional Tribunal, a constitutional review body that the NLD had previously failed to establish.93“Appointment and Assignment of Chairman and members of Constitutional Tribunal of the Union,” The Global New Light of Myanmar, February 9, 2021, gnlm.com.mm/appointment-and-assignment-of-chairman-and-members-of-constitutional-tribunal-of-the-union/ The military has not yet begun systematically interfering with the lower courts, but those courts have little substantive power over the cases that they are hearing, and have mostly been slow or stalled since February 1.

After substantially weakening the independence of the courts, the military began changing the legal framework, including laws affecting creative expression. While military orders—issued under the spurious claim that the military had lawfully declared a state of emergency—are disguised as “directives,” “laws,” and “amendments,” they are best understood as a return to the previous regime’s system of rule-by-decree.94“Unlawful Edicts: Rule by Decree under the Myanmar Tatmadaw,” International Center for Not-for-Profit Law, March 15, 2021, icnl.org/wp-content/uploads/03.2021-LEGAL-BRIEFER-Rule-by-Decree-by-Myanmar-Tatmadaw.pdf From February 13–15, the military set about undermining due process and restricting some of the human rights that creative artists and others had gained over previous years. They first “suspended” legal safeguards on surveillance and court oversight of detentions, and restored a former military-era law criminalizing failure to inform the police of overnight guests.95The military “adopted” the Amendment of Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens, suspending Sections 5, 7, and 8 for the period of the state of emergency. The privacy law was adopted by the NLD to establish safeguards in response to decades of intrusive surveillance and searches by Myanmar’s security services. The “suspended” provisions previously gave people some limited protection from invasion of privacy, surveillance, spying, and detention without court oversight: “Amendment of Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of the Citizens,” The Global New Light of Myanmar, February 14, 2021, gnlm.com.mm/amendment-of-law-protecting-the-privacy-and-security-of-the-citizens/; The military also “adopted” the Fourth Amendment of the Ward or Village Tract Administration Law to amend Sections 13, 16, 17, 27, 28, and 33. The amendment restored the crime of failing to inform local authorities of overnight guests, on penalty of a criminal record and a week in prison: “Fourth Amendment of the Ward or Village-Tract Administration Law,” The Global New Light of Myanmar, February 14, 2021, gnlm.com.mm/fourth-amendment-of-the-ward-or-village-tract-administration-law/ This enabled the military to detain individuals for longer than 24 hours without the need to present them before a court, a principle commonly known as “habeas corpus,” and reimposed the old fear of absolute military control over both public and private spaces.

In parallel to widespread detentions and arrests of creative artists, the military also attacked Myanmar’s already weak legal safeguards for creative expression, issuing illegitimate “amendments”—effectively military orders without any form of lawful legislative process—that added to Myanmar’s range of provisions used to criminalize speech. One of these “amendments” to the Penal Code added a new crime, Section 505A, of “spreading false news” with no definition of “false” and with provisions vague enough to be applied to creative expression.96The Penal Code amendment adds a new crime under Section 505A of “causing fear” or “spreading false news” with a maximum sentence of three years in prison and a fine: “Myanmar Ruling Council Amends Treason, Sedition Laws to Protect Coup Makers,” Irrawaddy, February 16, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-ruling-council-amends-treason-sedition-laws-protect-coup-makers.html; “15 February 2021,” The Global New Light of Myanmar, accessed October 1, 2021, gnlm.com.mm/15-february-2021/#article-title The amendment also introduced more serious punishments for a range of colonial-era crimes relating to expression, such as treason, sedition, and incitement to mutiny.97The amendment broadened Section 505(a), an already vague clause on incitement to “mutiny,” to criminalize encouraging disobedience and disloyalty to the military and government with a maximum of three years of imprisonment: “Myanmar Ruling Council Amends Treason, Sedition Laws to Protect Coup Makers,” The Irrawaddy, February 16, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-ruling-council-amends-treason-sedition-laws-protect-coup-makers.html; It also broadened Section 124, which relates to the pre-democratic crime of treason, to include several repetitive crimes of criticizing or hindering the military, with a maximum sentence of 20 years imprisonment. The military’s amendment of the Penal Code’s high treason provision, Section 121—which is punishable by death—is now so broad as to conceivably include creative expression: “15 February 2021,” The Global New Light of Myanmar, accessed October 1, 2021, gnlm.com.mm/15-february-2021/#article-title In a further attack on due process, the military illegitimately amended the Code of Criminal Procedure, stripping away basic legal rights to fair treatment by allowing warrantless arrests for serious crimes including treason and sedition, and making them non-bailable.98“15 February 2021,” The Global New Light of Myanmar, accessed October 1, 2021, gnlm.com.mm/15-february-2021/#article-title On August 3, the military also illegitimately amended the scope of Myanmar’s Counter-Terrorism Law to include other crimes, some of which may encapsulate creative expression and could be used against creative artists. In a reversal of normal legal standards, the Counter-Terrorism Law places the burden of proof upon defendants, so that those charged with terrorism are essentially guilty unless they can prove themselves innocent.99The Counter Terrorism Law was “amended,” increasing the maximum term of imprisonment from three to seven years for the crimes of “persuasion” and “propaganda.” “Myanmar Coup Chief Amends Counterterrorism Law,” Irrawaddy, August 3, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-coup-chief-amends-counterterrorism-law.html On November 1, another illegitimate amendment to the Broadcasting Law brought back media-specific criminal laws such as imprisonment for running pirate radio stations, rolling back a decade of liberalizing reforms.100“Criminal media laws return, internet threatened,” Free Expression Myanmar, November 3, 2021, freeexpressionmyanmar.org/criminal-media-laws-return-internet-threatened/ These legal changes have collectively resulted in a return to a similar legal framework last seen under the previous period of military rule, in particular, the infamous Emergency Provisions Act, under which the military could detain people, including creative artists, indefinitely at whim.101The Emergency Provisions Act was adopted in 1950 and repealed by the NLD in 2016. It included the notorious Section 5(j) which was regularly used to arbitrarily punish those who express themselves: Wa Lone, “Myanmar repeals emergency law used for decades to silence activists,” Reuters, October 4, 2016, reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-law-idUSKCN1241JZ

Creative outpouring

For the past 10 months, the military has suppressed protests, free expression, and creativity in a giant show of disproportionate violence.102“Cities terrorised as junta escalates lethal violence against public on Armed Forces Day,” Myanmar Now, March 27, 2021, myanmar-now.org/en/news/cities-terrorised-as-junta-escalates-lethal-violence-against-public-on-armed-forces-day As the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Tom Andrews, noted, “the generals have declared war on the people.”103Tom Andrews, “It’s as if the generals have declared war on the people of Myanmar: late night raids; mounting arrests; more rights stripped away; another Internet shutdown; military convoys entering communities,” Twitter, February 14, 2021, twitter.com/RapporteurUn/status/1361025118642843649 Yet despite—or perhaps because of—the crackdown, creativity has flourished as people in Myanmar have looked for new and innovative means to express themselves and to protest against the dramatic closure in the democratic and civic space.

People reacted quickly to the coup nationwide via a range of protest actions. Kyaw Zwa Moe, journalist and editor of independent Myanmar media outlet The Irrawaddy, indicated a few weeks after the coup that there were four key forces behind the movement: “Generation Z; the previous political generations, including the ’88 Generation guided by prominent student leader Ko Min Ko Naing; civil servants staging the civil disobedience movement, or CDM; and the elected NLD. The public is together with them.” While the demands are similar to those made by the previous generations, he adds that this is the most creative movement in the history of the country: “This uprising looks like a street performance with colorful costumes, stylish fashions, and weird wizards abounding. But we can all see how serious and determined these young people are on their mission to eradicate the military dictatorship and return to democracy.”104Kyaw Zwa Moe, “Defying Myanmar Military Regime in Harmony: Gen Z and Other Main Forces,” The Irrawaddy, February 13, 2021, irrawaddy.com/opinion/commentary/generation-z-forefront-uprising-myanmar-military-rule.html

Civil society, including the creative community, has played a leading role, and longtime professionals and budding artists alike responded with an explosion of creative expression and political art, from revolutionary songs, street graffiti, and body tattoos, to silent protests, murals, and poetry.105Robert Bociaga, “Myanmar artists draw on creative arsenal,” Nikkei Asia, October 6, 2021, asia.nikkei.com/Life-Arts/Arts/Myanmar-artists-draw-on-creative-arsenal; Emiline Smith, “In Myanmar, Protests Harness Creativity and Humor,” Hyperallergic, April 12, 2021, hyperallergic.com/637088/myanmar-protests-harness-creativity-and-humor/ On the first day of the coup, people in Yangon took to their balconies, yards, and streets to bang pots and pans—a traditional cultural expression to scare away evil spirits—every evening, and the protest quickly spread nationwide.106“Anti-coup protests ring out in Myanmar’s main city,” Reuters, February 1, 2021, reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-politics/anti-coup-protests-ring-out-in-myanmars-main-city-idUSKBN2A139S Artists joined them, projecting large-scale versions of their work featuring the three-finger salute onto buildings in Yangon every night.107Suyin Haynes, “Myanmar’s Creatives Are Fighting Military Rule With Art—Despite the Threat of a Draconian New Cyber-Security Law,” Time, February 12, 2021, https://time.com/5938674/myanmar-protest-digital-crackdown/ The next day, health workers, already busy dealing with COVID-19, kick-started a national civil disobedience movement, and teachers, students, factory workers, engineers, miners, civil servants, and large labor unions quickly joined in.108“Teachers, students join anti-coup campaign as hospital staff stop work,” Frontier Myanmar, February 3, 2021, frontiermyanmar.net/en/teachers-students-join-anti-coup-campaign-as-hospital-staff-stop-work/; “Myanmar Copper Miners Join Anti-Coup Strike,” Irrawaddy, February 6, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/myanmar-copper-miners-join-anti-coup-strike.html; Elizabeth Paton, “Myanmar’s Defiant Garment Workers Demand That Fashion Pay Attention,” The New York Times, March 12, 2021, nytimes.com/2021/03/12/business/myanmar-garment-workers-protests.html; Tint Zaw Tun, “Trade Union in Myanmar to prosecute those taking legal action against CDM participants,” The Myanmar Times, February 10, 2021, mmtimes.com/news/trade-union-myanmar-prosecute-those-taking-legal-action-against-cdm-participants.html Small street protests began on February 4 in Myanmar’s second largest city, Mandalay, followed by larger protests there and in Yangon and the military’s own city, Naypyidaw.109Kyaw Ko Ko, “Mandalay citizens protest against Tatmadaw rule,” The Myanmar Times, February 4, 2021, mmtimes.com/news/mandalay-citizens-protest-against-tatmadaw-rule.html; “There have been some minor protests against the military coup,” VOA News, February 3, 2021, burmese.voanews.com/a/myanmar-civil-disobedience-movement-/5762587.html; “Thousands of Myanmar protesters in standoff with police in Yangon,” Al Jazeera, February 6, 2021, aljazeera.com/news/2021/2/6/thousands-of-myanmar-protesters-face-off-with-police-in-yangon The protests were diverse, inclusive, and organic in nature, quickly growing to include hundreds of thousands of people, with vocal participation and leadership by the country’s youth.110Richard C. Paddock, “As Bullets and Threats Fly, Myanmar Protesters Proudly Hold the Line,” The New York Times, February 9, 2021, nytimes.com/2021/02/09/world/asia/myanmar-coup-protest-photos.html They were the country’s largest protests since the 2007 Saffron Revolution.111“Myanmar coup: Tens of thousands join largest protests since 2007,” BBC News, February 7, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-55967959

The first days after the coup were largely peaceful, with very few members of the military visible on the streets. That changed on February 8, when police fired water cannons at thousands of peaceful protesters in Naypyidaw, and the military banned assemblies of more than five people and imposed a nighttime curfew.112“Myanmar coup: Police use water cannon on protesters,” BBC News, February 8, 2021, bbc.com/news/av/world-asia-55977478; “Myanmar junta imposes curfew, meeting bans as protests swell,” AP News, February 8, 2021, apnews.com/article/myanmar-anti-coup-protest-fd4252fbd800caa5d457de9dd65293b7 The next day the police began using lethal force, firing rubber bullets and live rounds at peaceful protesters and injuring at least six people.113“Six Protesters Injured After Myanmar Police Fire on Protest,” Irrawaddy, February 9, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/six-protesters-injured-myanmar-police-fire-protest.html The military also appeared on the streets, issuing arrest warrants for protest leaders and detaining at least a hundred protesters.114Michael Safi, “Myanmar: troops and police forcefully disperse marchers in Mandalay,” The Guardian, February 15, 2021, theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/15/myanmar-internet-restored-protesters-army-presence-aung-san-suu-kyi; “Myanmar coup: Troops on the streets as fears of crackdown mount,” BBC News, February 15, 2021, bbc.com/news/world-asia-56062955; Kyaw Ko Ko, “Protest crackdown begins in Myanmar, over 100 nabbed in Mandalay,” The Myanmar Times, mmtimes.com/news/protest-crackdown-begins-myanmar-over-100-nabbed-mandalay.html On February 19, 19-year-old student Mya Thwet Thwet Khine was shot by police while hiding in the street, making her the first “martyr” of the anti-military protests.115“Myanmar Student Dies 10 Days After Being Shot by Police at Anti-Coup Protest,” Irrawaddy, February 19, 2021, irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-student-dies-10-days-shot-police-anti-coup-protest.html On March 4, 19-year-old singer, dancer, and tae kwon do champion Kyal Sin, nicknamed Angel, was shot in the head during a Mandalay protest. Prior to joining the protest, she posted her blood type on Facebook and left the note: “If I was wounded & couldn’t be back to good condition, pls do not save me. I will give the left useful parts of my body to someone who needs it.”116Yanghee Lee, “19 yr old Kyal Sin, Angel in English, left letter saying ‘If I was wounded & couldn’t be back to good condition, pls do not save me,’” Twitter, March 3, 2021, twitter.com/YangheeLeeSKKU/status/1367290454908104706

On March 7, four rock musicians secretly gathered at an abandoned house in Yangon to record a song about security forces shooting to kill. They called it “Headshot”:

Give us back our democracy. Now!

Release every innocent one you captured. Now!

Whose power was taken away? Ours!

We, the people, have the power

Down with the military regime, the war-dogs

Biting the hands that feed them

Of those four musicians, two fled to the jungle along the Thai-Myanmar border, an area protected by ethnic armed organizations, where one, Idiots lead singer Raymond, died of malaria in June. Another went underground, and the fourth went overseas. Three of the group were accused of sedition and had their photos included in the daily wanted lists on military-run television.117Emily Fishbein and Athens Zaw Zaw, “‘Rock and Roll Is at Its Most Beautiful Stage When It’s Free,’” Rolling Stone, September 6, 2021, rollingstone.com/music/music-features/censorship-myanmar-coup-rock-free-speech-1215817/

In the very early days, much of the protest artwork featured Aung San Suu Kyi’s image, but gradually the iconography became more diverse and inclusive.118Jackie Fox, “Myanmar pro-democracy artists vow: ‘We will win,’” Raidió Teilifís Éireann, May 30, 2021, rte.ie/news/2021/0528/1224494-myanmar-coup-four-months/ Although the regime’s sweeping censorship quickly curbed the activities of commercial artists, many began creating protest art for free. An ethnic Kayin/Karen cartoonist, Saw Seltha, responded to the coup by using his art to poke fun at the military and as “happy medicine” so people would feel less fearful. He was not without his doubts, however. In an interview, Saw Seltha said, “I feel sad, and even sometimes guilty. While I sit and draw cartoons, someone is dying at the same time.”119Robert Bociaga, “Myanmar artists draw on creative arsenal,” Nikkei Asia, October 6, 2021, asia.nikkei.com/Life-Arts/Arts/Myanmar-artists-draw-on-creative-arsenal?