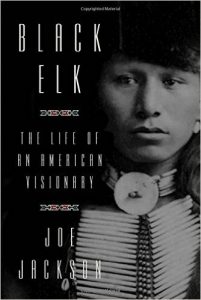

Joe Jackson’s Black Elk is the winner of the 2017 PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography. The following is an excerpt from the book.

Joe Jackson’s Black Elk is the winner of the 2017 PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography. The following is an excerpt from the book.

Submissions and nominations for the 2018 PEN Literary Awards are now open and will be accepted through August 15, 2017.

Extinction loomed in his life from the day he was born. It waited over the horizon like the thunderclouds rolling across the Plains. He feared those storms and the gods perched in their black folds. His second cousin Tsunke Witko, whom whites called Crazy Horse, told him all would be well if he submitted to Their will. He’d been given a gift, a Great Vision to save his people. If he acted on it, all would be well.

He was not alone in such fear. His people, the Oglala Lakota—called Sioux by their enemies—felt the apocalypse first and foremost with the disappearance of the buffalo. The vast herds remembered fondly by grandparents were doomed by the mid-nineteenth century. By 1842, the annual kill of Pte by civilian hunters exceeded 2.5 million; between 1850 and 1885, the railroads transported more than 75 million hides to eastern factories, where they were turned into gun belts and upholstery for high-end furniture. “Kill every buffalo you can,” Col. Richard Irving Dodge told an English sportsman. “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.”

Perhaps, like a river, Pte had drained underground. The Lakota believed that the bison came from the womb of the earth, and in evil times returned. Wind Cave in the Black Hills was that route to the underworld; at least, so said the medicine men, and Black Elk did not question them. His was a family of medicine men, stretching back for generations. Before he was Black Elk, still known by the childhood name Kahnigapi, or “Chosen,” he knew that only the foolish discounted the warnings of seers and holy men. They spoke of a new people who could not be stopped, no matter how many were killed. “They will be a powerful people, strong, tough,” the holy men admonished. “They are coming closer all the time.”

The most famous prophecy was that of Sweet Medicine, the powerful seer of their friends the Shahila, or Cheyenne. He warned of a “good-looking people, with light hair and white skin” who would come from the east in search of a “certain stone.” At first there would be just a few, but more would come, killing off the animals of the earth with an instrument that “makes a noise, and sends a little round stone to kill.” They’d replace the old four-leggeds with a new one with white horns and a long tail. They’d bring a drink that drove men crazy, and take the tribe’s children to teach them their ways. But these children would learn nothing. They would be shadows, lost between worlds.

Neither resistance nor reason could stop them, Sweet Medicine warned. “[W]hat they are going to do they will do.” Instead, the People would change: “In the end of your life in those days you will not get up early in the morning; you will never know when day comes; you will lie in bed; you will have disease, and will die suddenly; you will all die off.”

The Lakota prophet was no more comforting. Drinks Water—sometimes called Wooden Cup—died about twenty years before Black Elk was born. Black Elk’s father told him of the vision, as had his father before him. And he, the grandfather, had been told by Tries To Be Chief, the old bachelor who served as Drinks Water’s helper. Thus, the story had to be true. In this vision, a strange race would weave a spider’s web all around the Sioux. In some versions, the web was made of iron. As Black Elk grew older, he recognized this as a variation of the Iktomi, or spider, story, and Drinks Water’s dream seems the first reference comparing whites to the Iktomi. At some subconscious level, the image was chilling. Myths are strange and powerful narratives with the power to “shape and direct [life], for good or ill,” wrote Richard Slotkin in an early version of his cultural history Regeneration Through Violence. “They are made of words, concepts, images, and they can kill,” and Drinks Water’s words would be fatal in every way. When the new people finished their web, he said, Oglalas’ lives would forever change. They would no longer live in their tipis: a tipi was warm in the winter, cool in the summer, and could be disassembled and moved in a pony drag to follow the herds. If the Grandfathers had meant for man to stay in one place, they would have made the earth stand still. But in the dominion of the Iktomi, the People would live in square gray houses rooted to the earth in a barren land. “When this happens,” said Drinks Water, “alongside of those gray houses you shall starve.”

The old man lay down after finishing his account and refused to rise. He would die soon, he told his family, and he wished to be cremated so thoroughly that nothing remained. His clan built his bonfire on the prairie west of Paha Sapa, and it burned four days. Its light could be seen from every direction, a grim beacon for a New World his people hoped they would never find.

This is an excerpt from Joe Jackson’s Black Elk, published by Farrar, Strauss and Giroux in 2016.