The PEN World series showcases the important work of the more than 140 centers that form PEN International. Each PEN center sets its own priorities, but they are united by their commitment to advocate for imperiled writers, promote literature from all cultures and in all languages, and advance the right of every individual to speak freely.

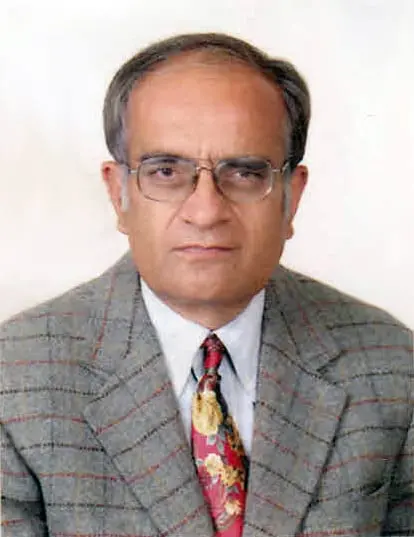

In this series, PEN America interviews the leaders of different PEN centers from the global network to offer a window into the literary accomplishments and free expression challenges of their respective countries. This month, we present an audio interview conducted by Polina Kovaleva with the President of Macedonian PEN, Ermis Lafazanovski.

TRANSCRIPT

POLINA KOVALEVA: First of all, thank you so much, and I am very excited to have this conversation with you about the Macedonian PEN. I am looking forward to hearing about what you guys are doing and what you are working on right now. So maybe you can elaborate on that?

ERMIS LAFAZANOVSKI: Thank you very much for having me and thank you for showing interest in the Macedonian PEN. Let me just briefly say a few words about the history of the Macedonian PEN because it is very important to what we are working on nowadays. For those who are not familiar with where Macedonia is, it is on the northern side of Greece between Serbia and Greece. After the dissolution of Yugoslavia, we shifted from the communist state to the democratic one. So for 20 years, we have been trying to improve our democracy.

The Macedonian PEN was established in 1978, so this year we have the 55th anniversary of the Macedonian PEN. This is a very important thing because we started working during the socialist or communist regime, so we were the first institution that dealt with the delicate democratic issues even in those times. After 1991, when Macedonia got its independence, the work of PEN has grown and improved in many ways. We became leaders in fighting for not only human rights, but also for writers’ rights and freedom of speech, but it was very difficult because these are the kinds of democratic issues on which people in Macedonia are still arguing. We are having a lot of these kinds of problems.

However, because we are a small PEN and a small country, we are gathering together with all Balkan PENs. We made a kind of network, it’s called Balkan PEN network. Inside there are members of Serbia, Slovenia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Albania, Bosnia, Kosovo, Montenegro, and we are trying our best to get Greece into our network. But unfortunately we have a dispute about the name of Macedonia. In 1991, when Macedonia applied and was approved as a member of the United Nations, it was approved under the name of former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia, and the European Union still called us the Former Yugoslav Republic. So, for the European Union we are not the Republic of Macedonia because of Greece, so in this name dispute, they claim that they have the right for the name of Macedonia because of Alexander the Great. The northern part of Greece is also called Macedonia, and this dispute is still ongoing. We are doing our best and we are happy to be a member of International PEN because in the International PEN we feel like ourselves, we feel accepted as Macedonians, and accepted as a family.

So speaking about the Balkan network, we are very pleased to have them among us, and I think that we can manage to resolve a lot of issues concerning freedom of speech and all kind of freedoms, but only together. In the Balkans, we have a very long history of unresolved problems. So we thought, if we are together, as a Balkan PEN network, then we can resolve our [domestic] problems in a better way. So this is what PEN is doing now. And I am the president of PEN now. Before me the host was in Serbia. They did a lot of good work. Every year they organized a conference to gather together.

Also, I forgot to mention that Turkey is also a member of our PEN. Because the situation in Turkey is now as it is, we are trying to help them, especially the writers who are in prison in Turkey. We are trying our best to help them; not only writers but also journalists. We as a Balkan PEN are trying our best to help. On the inside level, we organize a regional conference every two years, where we discuss the inside problems that we are having in Macedonia with freedom of speech and freedom of expression and so on.

This is why it is a very good opportunity to come to Ukraine. It is one thing to hear about the issues in Ukraine from the outside, and it is another thing to be in the inside and to speak with people, because we also have problems with propaganda, and now, especially for me, the situation is more clear, especially after the conversations I had with people about the media and propaganda and freedom of speech. Now I can use that to check the situation in Macedonia.

KOVALEVA: You already touched upon the kind of challenges that you have in the region. Is there anything else that you guys are struggling with?

LAFAZANOVSKI: Well, of course, we are struggling with financial problems because we are a poor country, but we have a little help from our friends who make donations and from our Minister of Culture. The new Minister of Culture in Macedonia is now a writer, a very well-known writer. We hope that he will understand our situation in PEN and will help us not with money, but with the projects, which we can apply to helping with the problems of freedom of speech that we have with journalists, writers, and so on.

KOVALEVA: Great. Can you tell us a little bit more about the literary tradition in Macedonia. Many people in America have no idea what Macedonian literature is, so could you please give us a little bit of an overview?

LAFAZANOVSKI: It is a simple question and a hard question at the same time. Why simple? Because after 1945, after the end of the Second World War, Macedonia as a republic inside of Yugoslavia was established. This is when the codification of Macedonian language happened and also the first association of writers.

In the 50 years of existence of the Republic of Macedonia, there were writers inside, writing mostly in the sense of socialism, for example, rural literature, and after 1991, it was an explosion of freedom. A lot of young writers started writing about the issues that are not only Macedonian, but also worldwide. This was the easy answer. But, however, we have a very long tradition because we have maybe one of the first universities in the world, dating back to the 10th century because St. Clement of Ohrid established one of the first universities. So, we have hundreds of years written in the old slavic language.

But the most important things in literature began at the end of the 19th century, when the identity of the nation was coming together and writers started using the very rich Macedonian folklore, folk narratives, folk songs, in their writings, trying to gather collections. So this was, and still is, the foundation of Macedonian literature. We have very rich poetry, I think it is the most well-known manifestation of Macedonia in the world, and that a lot of our American friends know about it through our Poetry evening, one of the greatest festivals of poetry in Europe. So a lot of poets come to that festival and then receive the Nobel Prize.

KOVALEVA: So in the end, maybe you could give us the names of some contemporary writers to follow?

LAFAZANOVSKI: Yes, of course. I am very glad that we have very young writers who are very famous in Europe and published books there. One of them is Goce Smilevski, he has also published books in America and in 20 or 30 languages all over Europe, then Venko Andonovski, Sasha [Aleksandar] Prokopiev, Lidija Dimkovska. She is our member and she is a well-known writer all over the world, but she lives in Slovenia, and she is running a festival now in Slovenia. So these are just a few names, the very top.

KOVALEVA: Thank you so much for the suggestions and for the interview! I wish you and Macedonian PEN all the best.