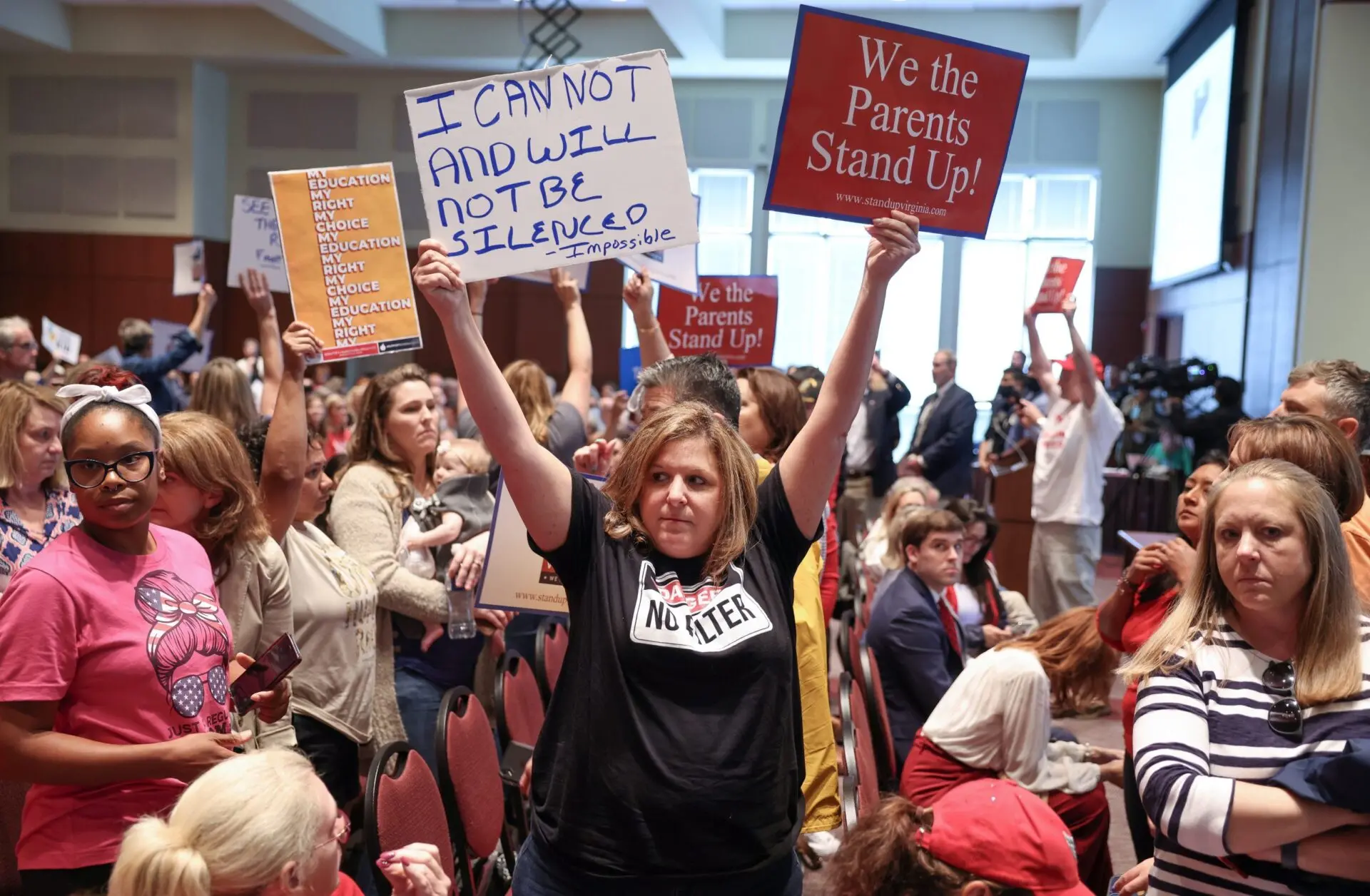

Three New Bills Become Law in Florida, Mississippi, and South Dakota

Monthly Roundup, March

This post is part of a series from PEN America tracking the progress of educational gag orders and censorious legislative efforts against educational institutions nationwide. These bills are tracked in our Index, updated weekly.

Three educational gag orders became law in March. In this month’s Roundup, we review those laws and a few more that could soon follow. Then we discuss a theme that runs through virtually all educational gag orders introduced in statehouses since January 2021: compulsory patriotism.

- Since January 2021, 175 educational gag order bills have been introduced in 40 different states

- 15 have become law in 13 states

- 103 are currently live

Of those currently live:

- 97 target K-12 schools

- 42 target higher education

- 57 include an avenue for punishment for those found in violation

New Educational Gag Orders

Here are the three educational gag orders that became law this past month:

- Florida’s HB 1557, better known as the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, prohibits public K-3 teachers from providing any instruction related to “sexual orientation or gender identity.” It permits such instruction in grades 4 through 12, but only in an “age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate” manner and “in accordance with state standards,” language that experts warn is alarmingly vague. The law also creates a private right of action, permitting parents to file civil suits against school districts they believe have facilitated illicit instruction.

- Mississippi’s SB 2113 prohibits public K-12 and higher education institutions from directing or compelling students to adopt or affirm certain ideas related to sex, race, ethnicity, religion, or national origin. They are also forbidden from making any “distinction or classification” of students on the basis of race, a provision that the executive director of the Mississippi ACLU worries might affect the legality of Black student groups like the University of Mississippi Black Law Students Association.

- South Dakota’s HB 1012, which Governor Kristi Noem championed, also became law in March. Among other things, it forbids public colleges and universities from requiring that students or employees “attend or participate in any training or orientation that teaches, advocates, acts upon, or promotes divisive concepts.” Note that a training or orientation program need not actively endorse a divisive concept to run afoul of this law. To merely teach one of them is sufficient. And while this law explicitly exempts divisive concepts discussed in the context of a “course of academic instruction or unit of study,” this exemption does not extend to freshman orientation, a lecture series, or many other campus events.

Other educational gag orders are rapidly approaching passage:

- We have written elsewhere about Florida’s HB 7, which currently awaits Governor Ron DeSantis’s signature.

- Tennessee’s HB 2670 passed both legislative chambers and will arrive on Governor Bill Lee’s desk shortly.

- Kentucky’s SB 1 passed the legislature; while Governor Andy Beshear is likely to veto it, Republicans may have the votes to override his veto.

- Wisconsin’s SB 409 passed the legislature, but Governor Tony Evers is likely to veto it.

- Georgia’s SB 377 and HB 1084 have passed one legislative chamber and are active in the other.

- Arizona’s HB 2112 and HCR 2001 (a proposed amendment to the state constitution) have passed one legislative chamber and are active in the other.

- Alabama’s HB 312 has passed one legislative chamber and is active in the other.

Compulsory Patriotism

One theme that runs through virtually every educational gag order is patriotism. On its own, that’s unremarkable. Every state in the country has education-related laws on the books designed to produce patriotic, civic-minded students.

But what legislators are doing now is different. Instead of simply requiring students to learn about, say, the Mayflower Compact or the importance of democracy, lawmakers are attempting to censor what they consider to be “anti-American” ideas, regulate instruction on slavery and racism, and prohibit conversations about contemporary injustice.

In other words, the purpose of these bills is not simply to cultivate patriotism. Rather, it is to make patriotism–or more specifically, a knee jerk and uncritical form of patriotism–compulsory.

There is a long history of such legally mandated patriotism in the United States. The Sedition Act of 1918 was used to imprison antiwar protestors during World War I. Until the 1940s, laws required students and teachers to stand for the Pledge of Allegiance. During the Cold War, teachers were compelled by law to swear loyalty oaths to the country. This all testifies to a strain of American censoriousness centered on patriotic sentiment, one that in recent decades schools had successfully kept at bay.

No longer. The current wave of educational gag orders has renewed this threat to America’s educational institutions. But whereas past legislation was primarily focused on pro-Communism or anti-war speech, the bills explored below largely target efforts to reimagine the role of race and racism in American history and culture.

The 1619 Project and Racism in American History

The most obvious and long-standing form of compulsory patriotism to appear in educational gag orders is a set of provisions restricting use of the New York Times’s 1619 Project. Conservative backlash against the 1619 Project is one of the central origin points of the current educational gag order movement. Sen. Tom Cotton’s “Saving American History Act,” introduced in June 2020 and one of the most popular models for state educational gag orders, declared that “the 1619 Project is a racially divisive and revisionist account of history that threatens the integrity of the Union by denying the true principles on which it was founded.” In a September 2020 speech, President Donald Trump accused the Times of “rewrit[ing] American history to teach our children that we were founded on the principle of oppression, not freedom,” and said that the 1619 Project bore “a striking resemblance to the anti-American propaganda of our adversaries.”

The 1619 Project has certainly not been free from criticism, but prohibiting its use in the classroom, even in conversation with other sources or theories, is a serious limitation on teachers’ freedom of expression. Such restrictions, writes historian Jonathan Zimmerman, miss “a huge opportunity to teach students what history actually *is*: an act of interpretation.”

Nonetheless, a desire to prohibit teaching the 1619 Project has persisted for nearly two years.

It can be found in Mississippi SB 2538, introduced in January 2021 – the first state-level educational gag order to be introduced anywhere in the country. According to the bill, the 1619 Project offers a “racially divisive and revisionist account of history that threatens the integrity of the Union,” and therefore ought not to be taught through use of any state funds. Instead, the bill declared–mistakenly–that the “true date of America’s founding is July 4, 1775.”

Thankfully, SB 2538 failed to advance. Since then, however, 22 other bills targeting the 1619 Project have been introduced. One of these, Texas SB 3, has become law. Currently, it is illegal in the state of Texas for a public K-12 teacher to require of his or her students “an understanding” of the 1619 Project. Though the precise meaning of this language is uncertain, its aim is clear enough: to prevent the Project from being taught or discussed. Via a state board of education policy, a similar ban is in force in Florida as well.

These are just the bills that explicitly prohibit the 1619 Project. Many more bills include an implicit ban. For example, South Carolina H 4392 would forbid educators from making use of any instructional material that could lead students to believe that:

With respect to their relationship to American values, slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to the authentic founding principles of the United States, which include liberty and equality.

Or that:

The advent of slavery in the territory that is now the United States constituted the true founding of the United States.

More or less identical language can be found in Texas SB3, as well as in 13 other bills introduced so far. Of these, 11 are currently under consideration, including two (South Dakota HB 1337 and Kentucky SB 138) that have already passed one legislative chamber.

Still another type of legislation permits instruction on historical racism and slavery, but only in a historically-misleading manner that exonerates America of their stain. Thus, New Hampshire’s HB 1255 would forbid teachers from promoting “any doctrine or theory promoting a negative account or representation of the founding and history of the United States of America in New Hampshire public schools which does not include the worldwide context of now outdated and discouraged practices.” Oklahoma HB 2988 prohibits teaching that “America has more culpability, in general, than other nations for the institution of slavery,” that “America, in general, had slavery more extensively and for a later period of time than other nations,” or that one race “is the unique oppressor in the institution of slavery” while another is its “unique victim.”

Similar logic can be found in Rhode Island’s HB 7539 and Kentucky’s SB 1, which passed the state legislature last week. The Kentucky bill requires all instruction in public K-12 schools to “align” with the following idea:

The understanding that the institution of slavery and post-Civil War laws enforcing racial segregation and discrimination were contrary to the fundamental American promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, as expressed in the Declaration of Independence, but that defining racial disparities solely on the legacy of this institution is destructive to the unification of our nation.

The Blanket Bans

Another set of bills takes a blunter approach. Instead of targeting specific historical topics for censorship, they propose simply to ban criticism of the United States.

For example, Kentucky HB 706 would prohibit any “revisionist history of America’s founding.” So does Kentucky HB 487, which also bans use of any material deemed to “disparage the fundamental American value of equality.” Iowa SB 2043 bars K-12 teachers from discussing the Pledge of Allegiance “in any manner” that one might reasonably understand to constitute “unpatriotic commentary on the United States.” And under Oklahoma SB 588, public school teachers would be unable to endorse, favor or promote socialism, communism, Marxism, or any form of “anti-American bias.” What constitutes “anti-American bias”? The bill does not specify, but violations are punishable by the loss of state financial support, state accreditation, or both. Another Oklahoma bill, SB 614, would extend that last set of prohibitions to public universities, too.

Indeed, many of these compulsory patriotism bills apply to higher education, including Kentucky HB 487 and Missouri HB 2129 and SB 645. These last two would require high school and university-level courses on American history to “promote an overall positive…understanding of the United States.”

Others seek to regulate whether or how a teacher may offer instruction critical of contemporary American society, especially on the issue of race. The most common provision bans teachers from addressing the claim that America or an individual state is “fundamentally or irredeemably racist.” Another common provision forbids any suggestion that racism is systemic or embedded in American institutions. This includes a North Dakota law, adopted last November, that prohibits public K-12 schools from teaching that “racism is not merely the product of learned individual bias or prejudice, but that racism is systemically embedded in American society and the American legal system to facilitate racial inequality.” Such a prohibition — now law — effectively blunts any honest discussion or even inquiry in schools concerning the role of race and prejudice in society, the racial dimensions of poverty, educational attainment, or even hiring and promotion practices in the workplace.

A similar prohibition is already in place in Florida. And in Minnesota, lawmakers are considering HB 3301, a bill that would prohibit teachers from requiring a student to examine “the role of race and racism in society, the social construction of race and institutionalized racism, and how race intersects with identity, systems, and policies.” In short, if not always in so many words, these bills view discussion of systemic racism – or of racism in general – as inherently unpatriotic and would render them illegal.

A Familiar Mistake

The history of compulsory patriotism in the United States is not an attractive one. Most Americans look back on the Sedition Act, the Red Scare, the Smith Act, and McCarthyism as stains on the American character, not as something to emulate today. Unfortunately, in a misguided attempt to regulate what teachers can and cannot say about this country, state legislators now appear intent on repeating their predecessors’ mistakes. In doing so, supporters of these bills are in fact proposing a vision of patriotism that is not only unquestioning, but fragile. Each month, as more educational gag orders become law, we come closer to replicating the anti-democratic mistakes of our past.

This update from PEN America was compiled by Jeffrey Sachs, Jeremy C. Young, and Jonathan Friedman.

Sign Up for Updates on Educational Gag Orders

To receive further updates on educational gag orders and censorious legislative efforts against schools and higher education nationwide, sign up below.