PEN America Symposium Celebrates 100 Years of Defending Free Expression and the Power of the Written Word

By Suzanne Trimel

(NEW YORK) — As leading literary luminaries gathered to celebrate PEN America’s centenary, the presence most deeply felt was that of the author unable to attend. Salman Rushdie had been set to speak at the event before a brutal assault in August left him recovering from grievous wounds.

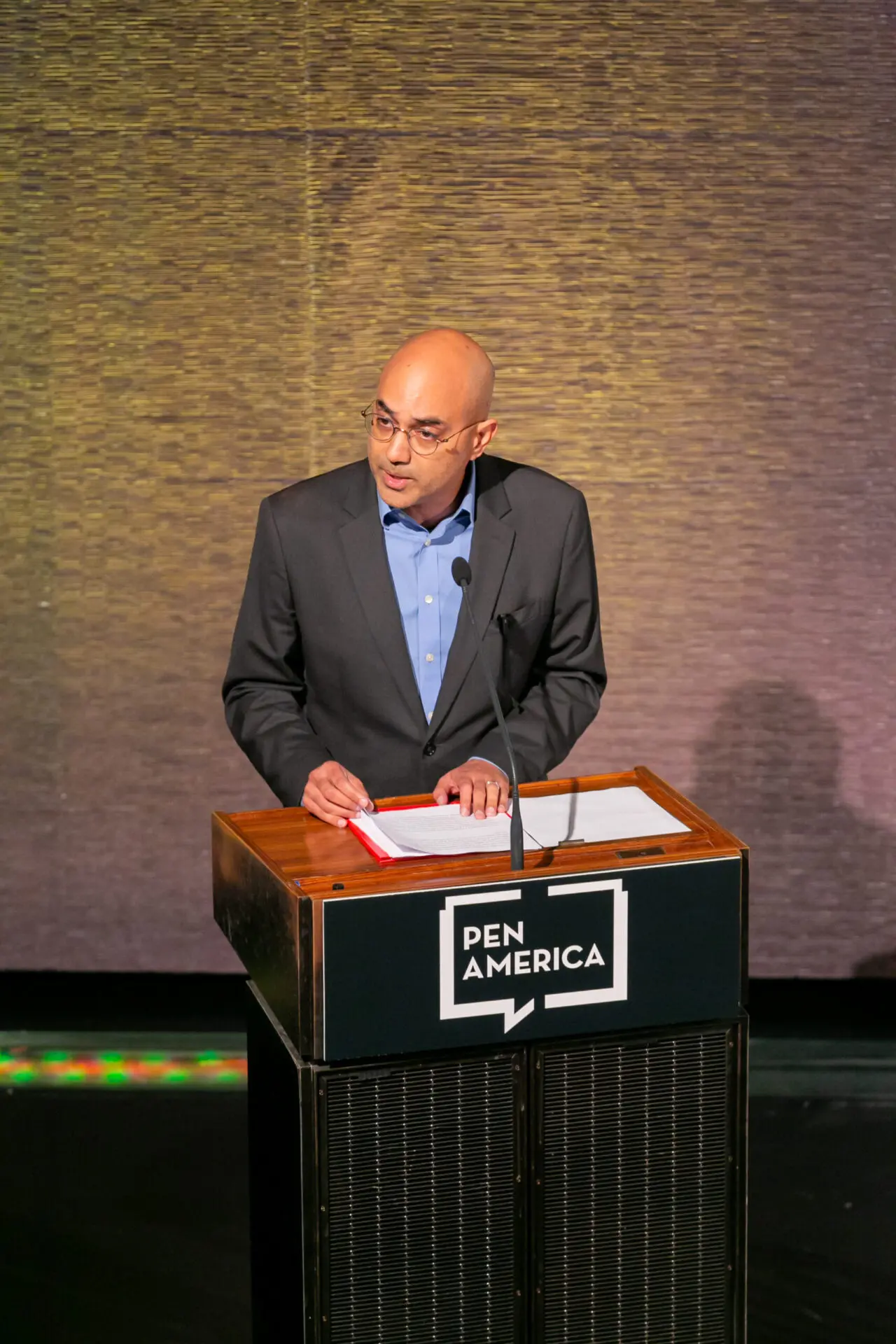

The discussion, “Words on Fire: Writing, Freedom and the Future,” brought authors Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Margaret Atwood, Jennifer Finney Boylan and Dave Eggers to the stage at the New-York Historical Society on Sept. 12, along with PEN America CEO Suzanne Nossel and President Ayad Akhtar, the novelist and playwright, and with many other distinguished authors in the audience.

Nossel opened the panel by referring to the attack on Rushdie, saying the violence “further crystallized what we were trying to do, and why. This latest assault was among the most personal and heart-rending of the cataclysmic events that have jolted PEN America over time, repeatedly reminding us of the fragility of our freedom.”

Adichie told the audience her response to the assault was to re-read Rushdie’s words.

“After the attack on Salman Rushdie, I could not stop thinking about it: the brutal barbaric intimacy of a person standing inches from you and forcefully plunging a knife into your flesh. And this because you wrote, because you spoke,” she said.

Re-reading Rushdie, she said, was “not only an act of defiant support but an act of meaning. It was important for me to remind myself how much words matter, how much books matter, how much stories matter.”

Akhtar had been set to interview Rushdie on stage. Instead, he recalled his first encounter with his work, after the “unanimous and profound disgust” about The Satanic Verses in Akhtar’s Muslim community during his high school years. When he went to college, Akhtar said he became one of the few in his community to read it.

While shocked by what he read at first, he also experienced for the first time what he called “authentic awe with a work of art.”

“I heard a call to language in service of truth even at the expense of belonging to my community. It was my first encounter with the sheer force of literature — and with the trouble it could get me into,” he said, drawing laughter from the audience.

Quoting Rushdie, he said: “What is freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.”

The authors also spoke powerfully about threats to free speech and the current climate of silencing and book bans, self-censorship, and the detention of journalists and artists worldwide.

Atwood, whose best-selling novel The Handmaid’s Tale has been banned worldwide, noted that both the dictators of Spain (Francisco Franco) and Portugal (António di Oliveira Salazar) had banned the book. On the subject of censorship she said wryly: “It’s hard to surprise me anymore. I was born in 1939.” Inevitably, the overturning of Roe v. Wade came up and her interlocutor onstage, Eggers, recalled her tweet in response to the ruling: “I told you so.”

Boylan took up the cause of the book bans sweeping American schools, focusing on books of relevance to the LGBTQ+ community that are the most challenged.

“It’s no secret why conservatives and others are trying to stop people from reading these books—their idea is that if they can erase our stories, it will be as if we don’t exist.”

She shared a story about a reader who came up to her on a Manhattan street to thank her for writing about transgender people, then stated that banning such books won’t erase the presence of LGBTQ+ lives “it just means that more and more of us will feel alone.”

Adichie talked about a different kind of silencing, and the “value of disagreement” as a profound and important aspect of free speech that must be protected.

“It has always troubled me how quickly people are fired for something they have said – not because I like or support what they say–I often don’t–but because it is a silencing that leads to a larger kind of silencing.”

Adichie said an American “addiction to comfort” permeates speech, to the point where there is a “kind of silencing in public discourse.”

After coming to live in the United States from Nigeria, she said, “I learned that in conversations about America’s difficult problems – like race and income inequality – the goal is not truth. The goal is comfort, comfort for all, ostensibly, but in reality, comfort for the more powerful.”

Akhtar took aim at the rise of sensitivity readers, whom publishers hire to flag potentially offensive characterizations relating to race, ethnicity, gender, religion and other concerns in manuscripts. “If there had been sensitivity readers early in my career, I wouldn’t have a career,” he said.

In PEN America’s 100 years defending free expression, Nossel described a series of “shocks to the system” that propelled those who value books and words to stand together against threats including the Nazi rise to power and the McCarthy era. The current challenges are another shock.

“Both around the globe and right here at home, we are in a world in which words risk losing their potency,” she said. “Where lying carries no stigma, and truth is lost in the cacophony, mistaken for yet another dose of cheap punditry. A world where people are being taught to avert their eyes, cover their ears and close their minds to avoid that which threatens, unsettles or contradicts.”