The PEN World series showcases the important work of the more than 140 centers that form PEN International. Each PEN center sets its own priorities, but they are united by their commitment to advocate for imperiled writers, promote literature from all cultures and in all languages, and advance the right of every individual to speak freely.

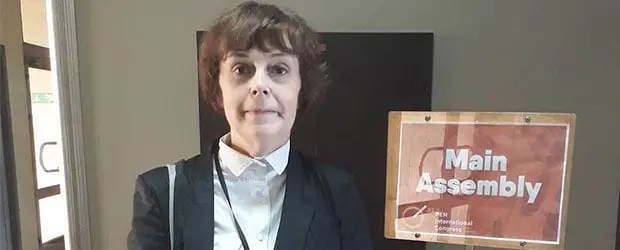

In this series, PEN America interviews the leaders of different PEN centers from the global network to offer a window into the literary accomplishments and free expression challenges of their respective countries. This month, we present an audio interview conducted by Polina Kovaleva with Romanian PEN President, Magda Cârneci.

POLINA KOVALEVA: First of all, thank you so much for your time and for agreeing to speak with me today about PEN Romania and Romanian literature. Could you tell us what projects PEN Romania is currently working on?

MAGDA CÂRNECI: We have several projects. We have established three or four events that happen every year. First of all, I want to mention the literary competition for young writers, both poetry and prose writers, which has been very successful. I am astonished by how many young people want to participate and have already participated in this competition.

KOVALEVA: What is the name of the event?

CÂRNECI: New Voices. It is a part of the international competition that is organized by PEN International under the same title. It is directed towards young writers, between 18 and 30 years old. We took this opportunity, offered by PEN International, and organized this competition on the national level, and it has been very successful. So I think that this can work in other countries as well. In fact, we had young poets who have arrived in the long list and then in the short list of the competition, and we are very proud of it.

Another annual activity is to participate in the regional European conference that takes place in Bled, Slovenia, around the beginning of May. It is an important meeting because representatives from many European PEN centers come there and talk about common themes. For example, the last one was One Hundred Years after the First World War, and how it was illustrated in the literature of the countries from the affected region. There were also writers coming from other continents—from America, from Australia, from Africa—so it was very interesting to be there and to talk and to hear what other writers say or write about this terrible war that has wounded so many countries.

Another event of ours is the national PEN award that we give each year in November to a poet, an essayist, or a prose writer, who has published a book on a subject that is related to the problems of PEN International, like freedom of expression, culture and memory, politics, freedom of movement, and all of these other issues that are so important to PEN International and to writers in general. An important aspect of our work in the last few years has been making us more visible in the public sphere and in the mass media, because we realized that it is important for the public to know the role of PEN International in preserving and fighting for the freedom of speech. So we gave interviews and went to radio stations and TV channels, and we were content to find out that people were interested in this subject, mostly younger people, who, in my view, are more cosmopolitan than the older people, more open to what happens in the rest of the world, more willing to be a part of this international, global mentality.

Also, we advocated for some writers who were in danger or in jail in other parts of the world because this is the mission of PEN International and we collaborate strongly with the headquarters in London. For example, we have organized a beautiful poetry evening in January 2017 for the young Palestinian poet Ashraf Fayadh, who was sentenced to death in Saudi Arabia for a volume of poems. PEN International organized a world event dedicated to this young poet, and we collaborated with many other PEN centers around the world as well.

KOVALEVA: Including PEN America.

CÂRNECI: Yes, exactly. It was a reading of poetry for him and it was very successful: It even appeared on a national TV program. We had very good echoes from this event. A good result of this enormous initiative was that Ashraf Fayadh was given only eight years of prison, not a death penalty. It was successful. And, by the way, I looked at PEN America’s website and I saw that you also participated in this global initiative, and I was very impressed by what you did.

Often, sometimes as often as every month, we have to advocate for bloggers, journalists, or writers who are in danger in other countries, mostly in Turkey, especially during this past year. Recently, we advocated for Aslı Erdoğan, a female Turkish writer who was in jail for many months. We wrote letters to the Turkish ambassador in Bucharest, published a letter of protest in the mass media, and sent many postcards to Turkey. We participated in this huge movement, which was also organized by PEN International, to help this courageous woman. Finally, she was released, on certain conditions, which is still a good result. Now Aslı Erdoğan has been invited to many places in Europe and she will do her best to help other Turkish writers who are also in bad situations.

We have numerous examples of activity like that, and I think that it is one of the main actions that we do constantly. It is not easy. Writers are not always accustomed to reacting quickly, to taking a stand, and to being courageous. It is a question of mentality and of education, and we have to insist, to repeat, again and again, until a sufficient number of people, writers, journalists, editors, and translators take a stand. In the beginning, it was very difficult: There were too few of us to organize everything, but little by little, people saw that our actions have an effect, and that it is important to be involved in this kind of activity.

I am very grateful that younger scholars from universities, not only from Bucharest, but from other big cities in Romania as well, collaborate with us and organize readings or evenings that are dedicated to poets and writers and involve students. This is really good. We also organize a World Poetry Day, which is on the 21st of March. It is not only a PEN International event, but a global event: It is a date established by the United Nations. Usually, we read poems by poets who are in danger or in prison, and we invite young students to read them.

A few months ago we advocated for Ernesto Cardenal, an important Latin American poet who was attacked by the government of his country, and PEN International asked national PEN centers to take a stand, and we organized a beautiful, successful evening in his support at the University of Bucharest, and then we published about it in the mass media. We have a website where we publish this kind of information in Romanian and in English. We also publish in mass media and in social media. This way, our message touches many people. Romanian PEN has become more vivid, more active, and more influential in the last two or three years because we succeeded in inviting and motivating young people who are now helping the center.

KOVALEVA: Wonderful! It is very great to hear all of this. Could you maybe elaborate on the Romanian literary tradition? Maybe give a short overview for people who do not know much about it?

CÂRNECI: It is not easy! But I will try to do my best. Romanian literature belongs to a country in the Central Eastern part of Europe. Romanian modern culture is based on traditional influences, but also on strong Western influences, mostly from France. Starting from the 19th century, throughout the 20th century, and up to the present, Romanian literature has struggled to synchronize itself with the literary trends that took place in France, because France has been the model of Romanian culture. Why? Because Romanian language is a Romance language, with very strong Latin origins, so for Romanians it is easy to learn and to speak French. French culture was the model for Romania until the 1970s, when the American model became very strong. My generation was probably the first generation in Romania that was able to learn English in school, and I, as well as many of my colleagues, were influenced by the American Beat Generation in poetry and other works, but the Beat Generation of the 1960s was very influential for us.

Romanian literature is rich and very diverse, split between the modern and the traditional. The most important tension is between the conservative and the avant-garde parts of it. Speaking about the avant-garde, I need to remind you that many of the most important avant-garde artists who changed the face of culture in the first half of the 20th century came from Romania, like Tristan Tzara and Dadaism, Victor Brauner and Visual Surrealism, Eugène Ionesco and the Theater of the Absurd, as well as important writers, such as the philosopher Emil Cioran and the historian of religion Mircea Eliade, who used to be a professor in the United States.

It is impressive to see how quickly the Romanian literature, which started only towards the end of the 19th century, succeeded in becoming synchronized with the rest of the European literature and was able to give such big names. I want to also mention the sculptor Constantin Brâncuși and the musician George Enescu, and there are many others. Most of them had to leave the country and to assert themselves in France and other Western countries, but nevertheless, they came from our Romanian culture, and many of them kept this connection with the origins and traditions.

I suppose that there is an avant-gardist element in modern Romanian literature and culture, which became influential in the European literature, and it is evident even now. We have many young artists who are so avant-gardist, so surrealist, so Dada, that it is amazing to know that there is, nevertheless, a continuation, even if the country passed through a Communist period of 45 years, something has been preserved and is now flourishing in a very diverse manner.

KOVALEVA: You mentioned the new emerging names. Could you tell us who exactly we have to follow, read, and be aware of?

CÂRNECI: Yes! For literature, I would name Mircea Cărtărescu, who is a well-known poet and prose writer, whose books have been translated into many languages, and who has been nominated, for several years now, for the Nobel Prize. He is really an extraordinary writer, I would say a genius. Also, for the visual arts, I would mention the names of Adrian Ghenie, who is a rather young painter, who sells his paintings for millions of dollars. He is one of the best paid visual artists nowadays, and it is amazing what kind of a career he has done at the age of 40. Another interesting visual artist is Mircea Cantor, who lives in Paris, and who is also renowned there and in other countries. We have many singers: Angela Gheorghiu is a well-know soprano singer, and she deserves this recognition because she is really wonderful.

We also have many good poets; it is said that we are a country of poets. There is a proverb in Romania that says: All Romanians are born poets. Well, it is not true, but it reveals the local Romanian spirit that is dedicated to lyrics. We have very good poetry, but it is very difficult to translate it well into other languages. Nevertheless, we have some poets who became very well-known in Europe, such as Ana Blandiana, who used to be the president of the Romanian PEN before me. She is a remarkable woman, her poems have been translated into many languages, she is invited everywhere to many literary festivals, so she is a star, as we say now. This gives you an idea of how it is in Romania.

KOVALEVA: Absolutely! Thank you so much, Magda. It was a great overview of your work and I wish you the best in the future.

CÂRNECI: Thank you!