A responsive series from PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, featuring original creative reportage by incarcerated writers, accompanied by podcast interviews with criminal justice reform experts on the pandemic’s impact in United States’ prisons.

Volume 8.0 Table of Contents

- Introduction: Caits Meissner

- Dispatch: Saint James Harris Wood

- Podcast: Alejo Rodriguez of Exodus Transitional Community

- Advocacy, Action and Resource Roundup

Introduction To Volume 8.0:

The Reentry Issue

Dear Readers,

Welcome back to Temperature Check. Over the past month, our team paused to assess our “rapid response” series as the pandemic continues with no foreseeable end in sight. In this period, we’ve been especially encouraged by our readers’ hunger to receive and share relevant information, volunteer and engage with the campaigns and efforts of various advocacy groups, news outlets, and organizers. More of these resources are featured in the advocacy section of this issue, and we hope you’ll continue to take action.

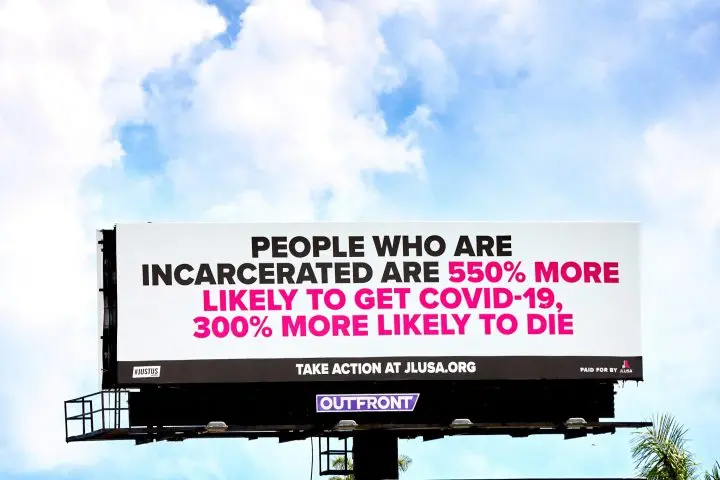

Since our last issue in mid-June, COVID-19 has tightened its grip on sites of detention. Local ad hoc efforts to control the virus have seen unprecedented actions across the country to reduce prison populations by the thousands. Rather than being motivated by an interest to protect the vulnerable, the decrease is largely due to prison officials refusing intake from county jails as a preventative measure. And thanks to the court closures, fewer have been sentenced during the pandemic, while parole officers are less frequently choosing to reincarcerate for low-level parole violations.

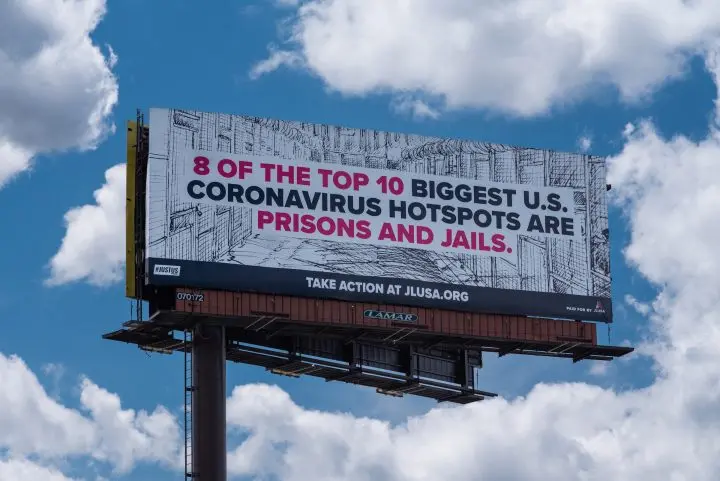

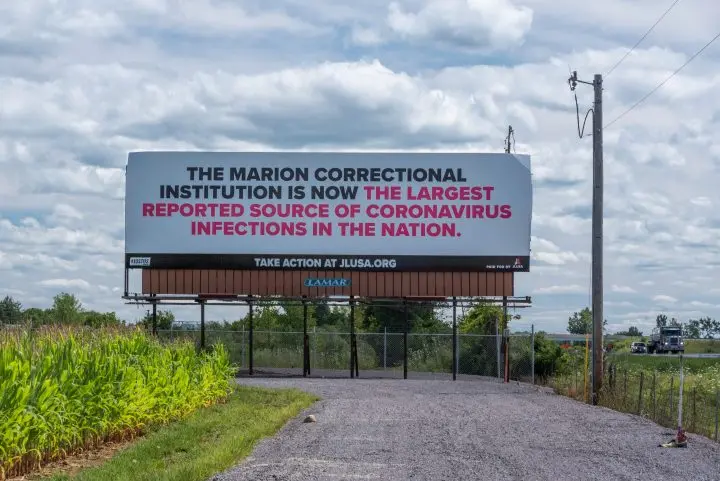

The explosive outbreak at San Quentin, reported on by 2020 PEN Prison Writing Award winner Juan Moreno Haines, has exposed the dire circumstances in the country’s many overcrowded correctional facilities. San Quentin was untouched by COVID-19 on May 30, when 121 new people were transferred into the facility. The next day, the first case was confirmed, and within weeks, hundreds had exploded. By July 30, the numbers shot up to 2,089. Mirroring this trajectory on a national scale, as of July 28, at least 78,526 people in prisons nationwide had tested positive for COVID-19—an 11 percent increase from the previous week.

Jails and prisons have reduced their populations in the face of the pandemic, but not enough to save lives, says the Prison Policy Initiative’s updated analysis. Advocates have been calling for more releases—and to lift the restrictive qualifications that incarcerated people must meet for consideration. Depending on the location, release might only be available, for example, to people imprisoned for parole violations—barring those with prior convictions for violent offenses or people who cannot provide evidence of adequate housing upon release. In others, preference for release is given to people with low-level offenses or only a year left on their sentence, elders who “pose less risk to public safety,” and clean rule violations records—according to a CDCR announcement, a violation might include anything from murder to cell phone possession.

And those who are released from prison and jails in less challenging times routinely face a series of obstacles that await: navigating a system of baffling and flailing social services, barriers to housing, lack of resources, the stigma of a criminal record. Now, during the pandemic, those coming home—often with little time to prepare—are met with diminished capacity from supportive relationships, decreased job options, and the surreality of leaving a technology desert to enter a world that has transitioned nearly entirely to the internet.

In this reentry focused issue of Temperature Check, we hear from Saint James Harris Wood, a PEN Prison Writing Award winner and widely published author about coming home just before the pandemic after serving a 18-and-a-half-year sentence—and watching the world slowly transition before his eyes.

Accompanying Wood’s offering is a conversation with one of my own mentors: Alejo Rodriguez. In this analogy-filled 40-minute podcast conversation, Alejo talks about his work with Exodus Transitional Community—a reentry organization based in New York—and how they’ve partnered with the Mayor’s Office to provide housing in a repurposed hotel for people recently released from Rikers Island. A special fact: While incarcerated, Alejo was a recipient of several PEN Prison Writers Awards and was featured in Doing Time: Anthology of 25 Years of Prison Writing, a collection of the best writing from the annual PEN Prison Writing contest.

Thank you for engaging.

In solidarity,

Caits

The PEN America Prison and Justice Writing Team

Caits Meissner, Program Director

Robert Pollock, Program Manager

Nicolette Natale, Spring 2020 Program Intern

Brookie McIlvaine, Spring 2020 Program Intern

Dispatches From Inside and Out

For Temperature Check, we’re commissioning justice-involved writers to share the direct impact of COVID-19 in prison—and after prison—through creative reportage.

Our eighth issue dispatch comes from Saint James Harris Wood, whose essay, The Swallow War, won first place in Essay in the 2018 PEN Prison Writing Contest. Wood had been on the road with his psychedelic punk blues band, The Saint James Catastrophe, when he picked up a heroin smoking habit. This inevitably led to a California high desert penal colony, where he reinvented himself as a writer of the darkly absurd.

Wood’s poetry, fiction, and essays have been published in The Sun, Adbusters, The Shop, Descant, Iowa Review, Esquire.com, Boulevard, Chapman, Rosebud, and several dozen other fairly reputable literary magazines in a half dozen countries, and won The Iowa Review’s Tim Ginnis Prize in 2011. In 2009, March Street Press published “Note Found in the Desert—the 50 lost poems of Saint James Harris Wood.” His forthcoming novel, Narcotic Field Theory, is slated for a Fall 2020 release on Vinal Publishing. His writings and music can be found at darklyabsurd.com.

Freedom is Complicated

by Saint James Harris Wood

Penitentiaries burst with uncharacteristic good will and advice in the months before releasing a convict back into the wild. Counselors guide me into the welfare state and while I am somewhat civilized, many of the fellows need the classes that teach them how to act right. The inmates themselves put together a list of resources available on the street to every ex-convict—thousands of dollars purportedly from a dozen sources including the Feds and the Parole Department—the only qualification: a term in prison; mental illness is a plus.

After one month of freedom I find that literally none of it is true. There are no resources for ex-convicts. Many of them leave prison and are soon on the streets, sleeping on the sidewalk. There are legitimate halfway houses (with long waiting lists) where ex-cons pay to share a room with two or four other fellows from the joint. For me personally, it wasn’t the loss of movement that the state used to punish me (I have a rich inner life that’s hard to suppress), my punishment was being forced to cohabitate with anti-social, angry, and mentally ill convicts, 95% of who were profoundly annoying. After 18½ years of it, I will never willingly share a room (or cell) with anyone ever again. I spent an extra month in prison in my single cell rather than go live in a halfway house for six months. I can imagine no scenario where I would want to live with or even hang out with 95% of the people I met in prison, convicts or staff. Some were boon companions while locked up, good musicians and chess players, and entertaining, charming lunatics; nonetheless, I have had my fill.

My brother and son pick me up at the gate and I feel like an utter refugee. I have nothing except five trash bags filled with thousands of pages of my writings, pictures, letters and crap I can’t shed. I have two other bags bursting with magazines and journals that published my work; but can’t carry them all. The cops don’t care and won’t help—always their fallback policy. I save a tattered thesaurus, and dump my published oeuvre in the trash. It’s discouraging, I don’t give a fuck… I just want the hell out.

Continue reading “Freedom is Complicated”

Works of Justice Podcast Interview: Alejo Rodriguez of Exodus Transitional Community

To learn more about reentry services during the pandemic, we talked to Alejo Rodriguez of Exodus Transitional Community and the Parole Preparation Project. Rodriguez was incarcerated for over 32 years and has turned his personal experiences—namely, being repeatedly denied parole because of a violent conviction—into powerful advocacy.

To learn more about reentry services during the pandemic, we talked to Alejo Rodriguez of Exodus Transitional Community and the Parole Preparation Project. Rodriguez was incarcerated for over 32 years and has turned his personal experiences—namely, being repeatedly denied parole because of a violent conviction—into powerful advocacy.

Nicolette Natale, PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program summer intern, talked with Rodriguez about how this discrimination is influencing decisions about who gets released during the pandemic, reentry efforts during a time of social distancing, and the overall importance of community building to end social and economic inequity.

Listen to the 40-minute conversation on our Works of Justice podcast:

Click here to access the transcript or listen on Apple Podcasts Spotify Google Play

Advocacy, Action and Resource Round-Up

REENTRY-FOCUSED ENGAGEMENT

“Time is just as valuable as money. You know, the idea of building community, working towards building community right now is probably one of the most critical investment[s] that can be made.” —Alejo Rodriguez on the Works of Justice Podcast

-

Apply to volunteer with the Parole Prep Project and join their October 2020 training.

-

Become an employer-partner, sponsor, or volunteer with the Exodus Transitional Community. You can also donate or buy items for Exodus.

-

To find opportunities to volunteer, visit this list for information on reentry services local to your community. FYI, Washington, D.C. is excluded from this list—learn more about opportunities through D.C.’s Reentry Action Network.

-

Learn why law enforcement and community advocates are promoting the #LessIsMoreNY legislation in New York State that could change how people are reincarcerated for technical parole violations and offer incentives for successfully following the terms of parole. Find out more about this bill at lessismoreny.org.

OTHER OPPORTUNITIES

-

Re:Store Justice has launched two guides to navigating hospitals for those in prisons and their loved ones. The first, “When You Are in The Hospital: FAQ For Incarcerated People About Transfer to Outside Hospitals,” can be downloaded and printed to send inside to incarcerated people. The second, “When Your Loved One Is in The Hospital: FAQ For Family Members and Loved Ones of Incarcerated People,” helps explain families’ rights and how to assist their loved ones while they are at the hospital.

-

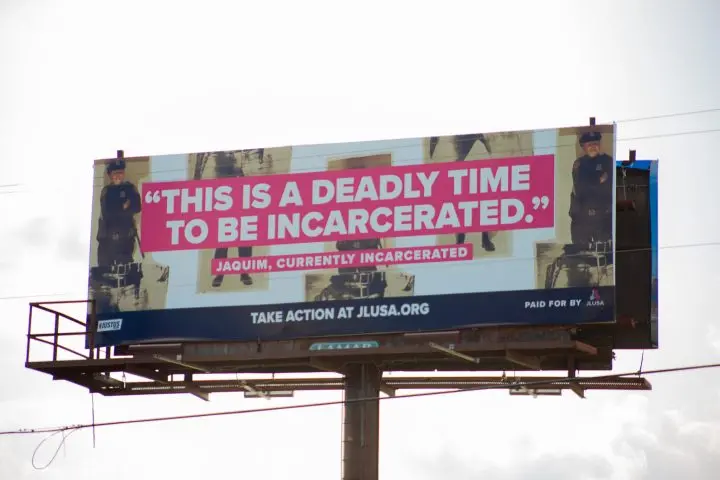

Join JustLeadership’s #JustUs letter campaign to send an email to your legislators, urging them to address the lack of emergency planning to manage disasters that impact correctional facilities and the criminal justice system.

-

Dances for Solidarity is seeking choreography collaborators interested in creating movement alongside people currently incarcerated in New York State prisons. In order to facilitate these collaborations, Dances for Solidarity is partnering with Black and Pink NYC, an organization that fights for prison abolition and supports LGBTQ folks affected by incarceration. Interested participants will be matched with a pen pal through Black and Pink, and Dances for Solidarity will provide letter templates, choreography prompts, and other support. Email [email protected] to get started!

-

A Little Piece of Light organization has launched an “Adopt A Pen Pal” program. So far, they have matched over 50 incarcerated women with a pen pal. If interested in joining this effort, email [email protected].

-

Mourning Our Losses is an organization that compiles obituaries for those who died of COVID-19 in prisons and jails—both incarcerated individuals and correctional officers—to “restore dignity to the faces and stories behind the statistics of death and illness from behind bars.” Read the moving obituaries here.