Penitentiaries burst with uncharacteristic good will and advice in the months before releasing a convict back into the wild. Counselors guide me into the welfare state and while I am somewhat civilized, many of the fellows need the classes that teach them how to act right. The inmates themselves put together a list of resources available on the street to every ex-convict—thousands of dollars purportedly from a dozen sources including the Feds and the Parole Department—the only qualification: a term in prison; mental illness is a plus.

After one month of freedom I find that literally none of it is true. There are no resources for ex-convicts. Many of them leave prison and are soon on the streets, sleeping on the sidewalk. There are legitimate halfway houses (with long waiting lists) where ex-cons pay to share a room with two or four other fellows from the joint. For me personally, it wasn’t the loss of movement that the state used to punish me (I have a rich inner life that’s hard to suppress), my punishment was being forced to cohabitate with anti-social, angry, and mentally ill convicts, 95% of who were profoundly annoying. After 18½ years of it, I will never willingly share a room (or cell) with anyone ever again. I spent an extra month in prison in my single cell rather than go live in a halfway house for six months. I can imagine no scenario where I would want to live with or even hang out with 95% of the people I met in prison, convicts or staff. Some were boon companions while locked up, good musicians and chess players, and entertaining, charming lunatics; nonetheless, I have had my fill.

My brother and son pick me up at the gate and I feel like an utter refugee. I have nothing except five trash bags filled with thousands of pages of my writings, pictures, letters and crap I can’t shed. I have two other bags bursting with magazines and journals that published my work; but can’t carry them all. The cops don’t care and won’t help—always their fallback policy. I save a tattered thesaurus, and dump my published oeuvre in the trash. It’s discouraging, I don’t give a fuck… I just want the hell out.

We drive down from San Luis Obispo (a lovely town scarred by the prison) to L.A. where we drop off my brother. In San Diego my son takes me to Nordstrom’s Rack and buys me some clothes and a pair of Nikes. As I throw my old prison kicks into the closest trashcan he suggests that this is a metaphor, but I am too shell shocked to figure the metaphor out. During my first week free, the parole department holds a big meeting with a hundred or so ex-cons and 20 people who represent rehabs, financial institutions, job training, the cops(!), homeless shelters and religious organizations. The room is crowded with impatient ex-cons and since the meeting is mandatory it feels like prison and I want nothing to do with it; though I do hook up with a credit union—most banks are wary due to my past robbery habit. The next day I see my parole agent and a state psychiatrist who is so overworked that he dispenses with me in two minutes though it feels like my PTSD could use a team of doctors. It would be nice to have an interesting psychiatrist, but the state can’t afford it and neither can I.

Upon realizing that I alone will have to figure out how to survive, I throw myself onto the mercy of social security and state welfare. Since I have miraculously survived for 66 years, the state recognizes my need. Any healthy convicts under 65 are out of luck. I am grateful for the monthly check and the food stamps, though it’s nowhere near enough to live. When you have no credit, a criminal background, and nowhere to live—an $800 check is an invitation to obliterate yourself with drugs, alcohol, or complicated sex—temporary reprieves that inexorably lead to a grim unending chase of the high, then homelessness. The monthly stipend allows the ex-con no home, only a few days relief, then nothing—an idiot cycle that can only be stopped by the government of the allegedly richest country in the world.

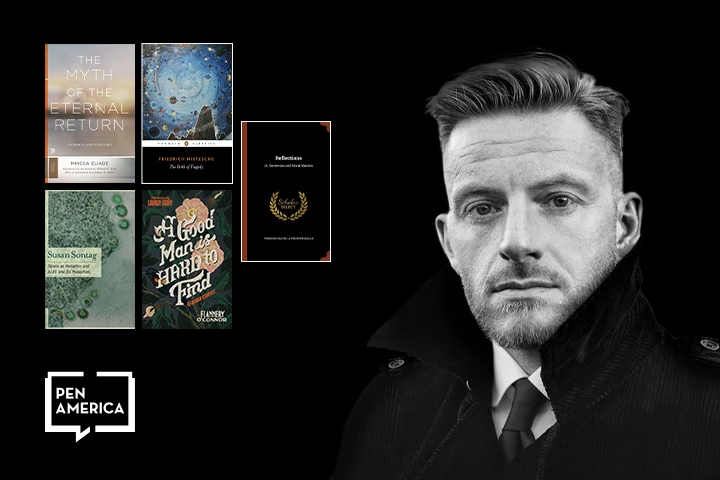

I miraculously sidestepped homelessness and disaster because I was taken in by pen pals from San Diego who read about my prison adventures in the Sun and other literary magazines. We traded letters for years, and that’s all they knew of me. When my release date was finally negotiated, they offered me a bedroom in their home in South Park, a beautiful chunk of American suburbia with nature trails, lush canyons and trees everywhere. These generous people resolved to support, feed and take care of me. I imagined that it would take two or three months to pull my life together, to get a job and find my own place. It took three months just to get my birth certificate and California ID. If not for my friends I would be sleeping in a downtown gutter with the mentally ill.

It’s weeks before I recognize that I have a form of PTSD that won’t let me feel free or comfortable. During the first month, I mention PTSD to various advisers and parole authorities who all agree that I am damaged, but can think of no good way out of it. A second meeting with the state psychiatrist can’t be arranged as he is too busy trying to spot murderers and arsonists. I don’t feel comfortable in stores or with groups of people that I don’t know. And while the good people who have taken me in are generous and constantly supportive, I hate it. Eighteen years in prison over-socialized me and I need to live alone, but getting my own place is going to be hard as fuck.

Then, at 3 months free, just as I get my ID and other ducks in a row . . . The Virus. I had a bitchin’ job set up with the U.S. Census folks, and a few weekly gigs playing blues and country at small bars and coffee houses. Now, the virus cancels everything. Practically the entire population is masked overnight like a science fiction movie. It’s impossible to describe the loss of connection now that no one has a face. I stop watching TV (Netflix only) because it’s “all virus all the time.” I’m trying to handle life, which has pretty much shut the fuck down. Life is suddenly on hold for the entire state. I figure I’m 66 and I’ve had a good run. I’ve already been locked up too much in recent decades. I go out every other day and play music on the streets and save the money towards renting my own domicile.

Six months free and I start to look for a place to live. I don’t know how any ex-convict is able to rent without a well-to-do relative to co-sign. I find out that even relatives would rather not co-sign for an ex-con with no credit. Landlords would ask me for $40-50 for a background check and I’d say, “I’ll tell you everything right now,” and I would, and I would never hear from them again. Four people said, “Well, it doesn’t matter, let’s just do the check,” and they’d take my $50 and I’d never hear from them again. Over a two month period I went to over 45 places (I don’t have a car) and was rejected by them all. The virus complicated the whole process and in the end I had to wage a major campaign to get a downtown room in a building that is in the center of San Diego’s latest homeless crisis. Thousands of people are permanently camped out on the streets all over downtown San Diego, making it look like a free-range refugee camp. It’s heartbreaking seeing people living on filthy sidewalks with no help in sight. Many of them just got out of jail or prison. I had a lot of help and it was really hard for me to get my own space. But I do finally feel free and I have my own room. And I will find my way.