Over the last month, three private universities (Brandeis, Columbia, and George Washington) suspended their chapters of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP). The details of each case vary; but together, they are united by a degree of opacity, in that university leaders have not been fully forthcoming in delineating how these student groups broke campus rules, or how the decision to suspend them was reached.

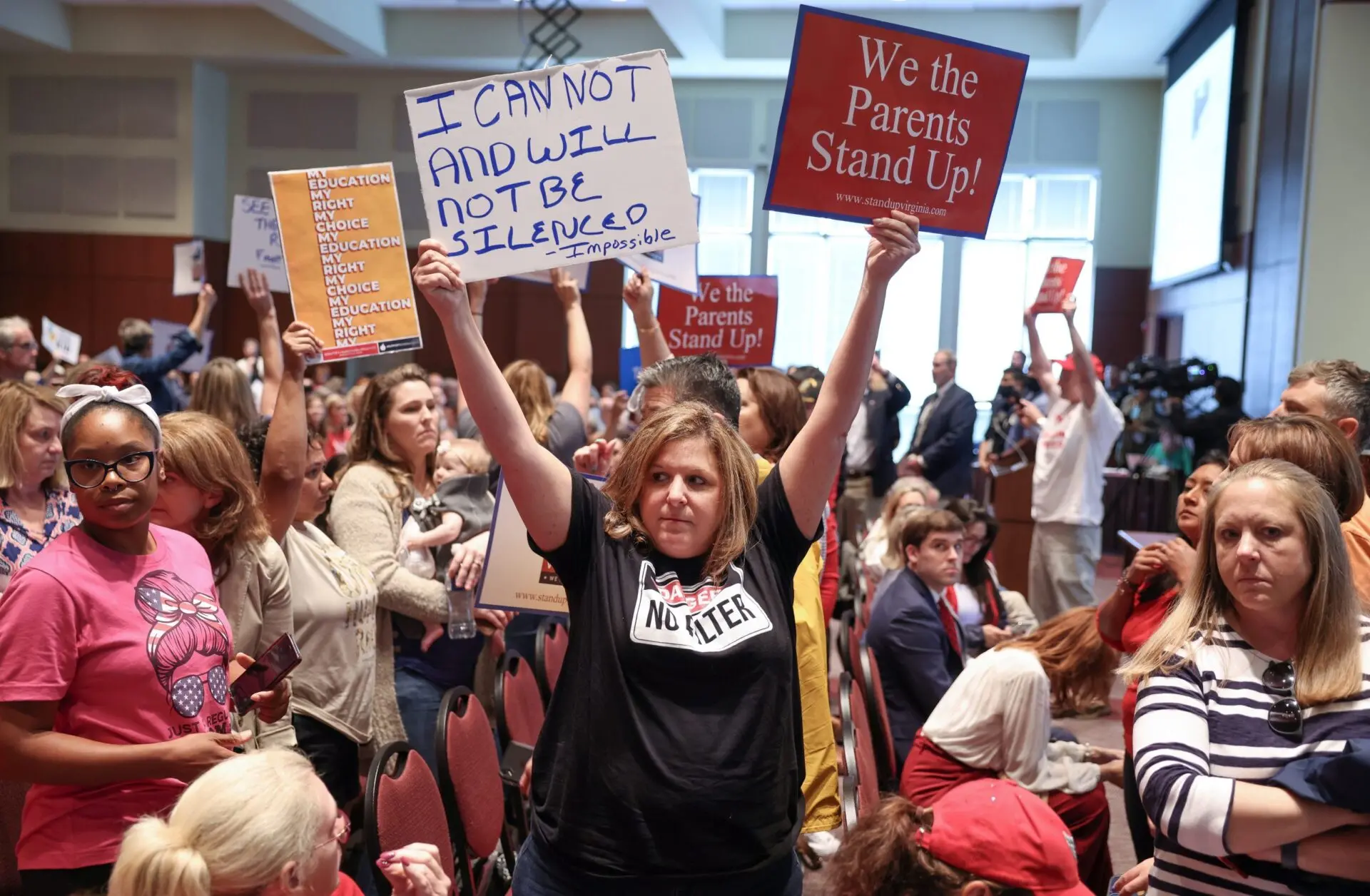

When it comes to supporting a climate for free speech and association on campus, that lack of transparency is concerning. Student organizations are an important form of expression and association; the bar for a university to suspend or shutter them should be high. And especially in a fraught political environment, opaque policy enforcement can chill speech, making people question whether universities will protect the expression rights of all consistently and evenhandedly.

These SJP chapters stand accused of promoting antisemitism, engaging in threats and harassment, and violating different campus policies. Perceptions of SJP have also been informed by the national group’s release of a “Day of Resistance” toolkit, which praised Hamas’ attack on Israel as a “historic win for the Palestinian resistance,” and designated SJP chapters as “PART of” a shared movement for “Palestine liberation” — not just “in solidarity” with it. Coupled with the group’s provocative tactics on campuses, the content of the toolkit fueled calls for the groups to be banned or disciplined, including from the Governor of Florida.

Some of SJP’s commentary is deeply objectionable, and even incendiary. But when it comes to punishing students for their political speech, offensive and even odious commentary is typically protected by the First Amendment and by many university policies that come close to a parallel with that constitutional standard. In the specific instances at hand, the absence of detailed information about how these universities reached the conclusion to suspend these groups have left the impression that they may be engaging in viewpoint-based censorship, and attempting to deliberately silence pro-Palestinian voices critical of Israel. Universities often cite personnel and privacy considerations as reasons why they cannot fully disclose the grounds for discipline of individuals for infractions that appear to center on speech. But these rationales for denying transparency would not seem to apply in these cases, where the suspensions are not directed toward individuals and have been based upon public conduct.

Take Brandeis: Administrators cited their SJP chapter for engaging in threats and harassment, and stated that the group’s support of Hamas, as an identified terrorist group in the U.S., was a violation of the student code of conduct. But the university has not spelled out what speech or conduct by the group crossed the line and violated policy. The group called on social media for the university to “take all necessary action” against the executive director of Brandeis Hillel, after he criticized a planned campus vigil and invited students to a discussion event timed to coincide with it. It is not clear if the SJP’s online response to the director was part of the grounds for the group’s suspension. It is also unclear if the suspension was based solely on speech, or also the group’s conduct.

Meanwhile, Brandeis policies specify that student clubs are to be governed by the student union, which says it was not consulted in the university’s decision. Said one student senator, “It sets a really dangerous precedent that the administration can choose pretty much at its own will whether or not to allow clubs to exist on campus.”

At Columbia, administrators said their chapter of SJP was suspended for “repeatedly” violating the university’s event policies, and barred the group from holding campus events through the end of the fall semester. The suspension occurred after the group organized an art installation and “die-in” on campus to protest Israel’s assault on Gaza, and after university leaders confronted a sit-in at the School of Social Work where students were charged with multiple policy violations for disrupting classes.

But while SJP promoted the disruptive sit-in, they did not organize it. And the events policy they are alleged to have violated has come under scrutiny, once it emerged that it was only recently altered by the administration, and without the approval of the faculty senate. This is against University rules and procedures, and has spurred harsh criticism from some faculty and the Columbia chapter of AAUP. For their part, the SJP chapter has challenged their suspension, stating that the policies were “deliberately vague” and poorly communicated.

At GW meanwhile, administrators said that a set of messages projected on the outside of the library by their SJP chapter violated its building use policy, and that students failed to comply when told to take it down. But the policy in question only delineates rules for posters on bulletin boards within the library, and does not spell out consequences for violations other than flyers being taken down. Members of SJP also claim that university police had initially allowed the light projections on the library to continue, before a university administrator intervened. Their chapter has nonetheless been suspended for at least 90 days and will continue to be unable to post communications on campus through May 2024. GW conducted an investigation into whether their policies were violated, and has said that its decision was based on the outcome of that probe, but the findings and conclusions have not been released publicly.

These cases could be debated endlessly, and indeed, alumni networks, student groups, faculty, and free speech advocates have been protesting. This is precisely the problem: when it comes to punishing people for speech, vague rules and opaque enforcement undermine faith in our institutions, and faith in our shared principles.

Suspending student groups may be an appropriate consequence for some policy violations. But those policies must be clearly communicated, well ahead of boundary-pushing demonstrations. And if student groups unambiguously violate them, they have a right to be told what their infractions were and to be afforded due process if they believe the penalties are inappropriate.

Each campus that has banned SJP or otherwise suppressed political activity without clear justifications has signaled to students and faculty that certain forms of pro-Palestinian protest may be risky. Taken alongside highly publicized doxxing campaigns targeting students, event cancellations, and mounting hateful speech directed at religious and racial minorities, these incidents have contributed to a national climate in which the space for free expression on campus is deteriorating.

The failure to communicate in detail about the grounds for these groups’ suspensions has undermined students’ rights, and worsened tensions at a time when they were already running high.

PEN America has suggested an array of measures that campuses should take to combat hate – including antisemitism and Islamophobia – while respecting free speech, in recognition of the serious toll that hate, intimidation, and even abstract threats can have on students’ sense of belonging, safety, and well-being. This can include fostering dialogue, facilitating education, condemning hate, and offering support and resources to the individuals and communities affected.

Research was contributed by Sam LaFrance.