Half-Free: How “Conditional Release” Continues to Limit Free Expression for Writers at Risk

Along with legal and physical harassment, detention, and state-sanctioned violence, authoritarian states are increasingly using “conditional release” and travel bans in order to stifle free expression. These forms of “non-release release,” a term coined by Jerome Cohen to describe juridical strictures on movement, can take many shapes, from the confiscation of passports and frequent forced in-person check-ins with local authorities to the Chinese system of qǔ bǎo hòu shěn, a kind of deferred sentencing that keeps alleged criminals out of prison but effectively enforces self-censorship. As these tactics lack the same kind of blunt instrumentation as outright imprisonment or excessive physical abuse—and are thus less prone to stoke international outrage—they are prevalent in countries that wish to give the cosmetic appearance of being less repressive without allowing any significant space for free expression. A government can avoid being listed at the top of the annual tallies of murdered or imprisoned journalists while still effectively silencing dissenting or critical voices, particularly abroad.

The strictures associated with conditional release serve to extend prison walls. Just as the incarcerated are under the constant watch of their jailers, so too are “non-release releases” subject to governmental surveillance and control. The difference between a prisoner who is confined to a cell and forbidden from contacting family or friends and an individual who is restricted from leaving the country and communicating with the outside world should be understood as a difference of scale. For example, Gui Minhai, a poet, author, and book publisher and one of the “Causeway Bay Bookstore Five”—a group of five booksellers based in Hong Kong who disappeared under mysterious circumstances in late 2015, only to reappear in Chinese state custody on the mainland—has been described as “half-free.” Such terminology, however, runs the risk of confusing the absence of physical prison walls with freedom. In Turkey, travel bans were used (and later revoked) to prevent authors like Aslı Erdoğan and Necmiye Alpay—who were both detained for several months and then released while facing trial—from traveling abroad to accept prizes and speak frankly about political conditions in their home country. The goals of incarceration and limited release are one in the same: to suppress free expression and to enforce silence.

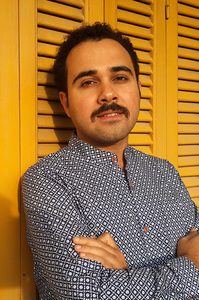

A number of individual writers at risk who are considered priority cases for PEN America are currently under conditional release or subject to travel bans. For example, Ahmed Naji, an Egyptian novelist, journalist, and winner of the 2016 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award, has been prevented from leaving the country for more than six months. In 2014, he was charged with “violating public modesty” after a citizen complained that reading a certain passage in Naji’s book, The Use of Life, caused him heart palpitations and a drop in blood pressure. Naji was initially found innocent before a higher court found him guilty in February 2016 and sentenced him to a two-year prison sentence. He subsequently won a challenge in May 2017 that overturned the original conviction and ordered a retrial. Despite his vacated conviction, Naji has been subject to a quasi-official travel ban; he was prevented from leaving Cairo by airport officials in July 2017, and authorities have advised that he will not be allowed to leave while he is awaiting a new trial date.

A number of individual writers at risk who are considered priority cases for PEN America are currently under conditional release or subject to travel bans. For example, Ahmed Naji, an Egyptian novelist, journalist, and winner of the 2016 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award, has been prevented from leaving the country for more than six months. In 2014, he was charged with “violating public modesty” after a citizen complained that reading a certain passage in Naji’s book, The Use of Life, caused him heart palpitations and a drop in blood pressure. Naji was initially found innocent before a higher court found him guilty in February 2016 and sentenced him to a two-year prison sentence. He subsequently won a challenge in May 2017 that overturned the original conviction and ordered a retrial. Despite his vacated conviction, Naji has been subject to a quasi-official travel ban; he was prevented from leaving Cairo by airport officials in July 2017, and authorities have advised that he will not be allowed to leave while he is awaiting a new trial date.

A similar limbo has befallen Khadija Ismayilova, an Azeri freelance investigative journalist and winner of the 2015 PEN/Barbara Goldsmith Freedom to Write Award. Ismayilova has for years been a vocal critic of official corruption and embezzlement, particularly surrounding President Ilham Aliyev and his family, and has been a staunch advocate for press freedom and human rights within Azerbaijan. In September 2015, Ismayilova was convicted on charges of embezzlement, illegal entrepreneurship, tax evasion, and abuse of power in a closed-door trial and sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison. On May 25, 2016, she was released on probation, but remains subject to a travel ban that precludes her from leaving the country. This December, Ismayilova was prevented from attending the ceremony to receive her Right Livelihood Award—often referred to as the “Alternative Nobel Prize”—in person, the last in a long series of speaking engagements and events she has been unable to physically attend.

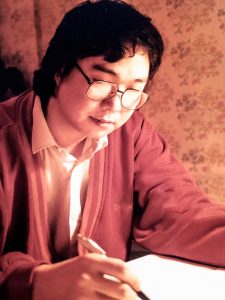

An even more murky fate has befallen Gui, who was abducted while on vacation in Thailand on October 17, 2015, and resurfaced in January 2016 when making what are believed to be forced confessions to distributing unlicensed books on the mainland and evading customs inspections. On October 24, 2017, Gui’s daughter Angela stated that the Chinese government had “released” Gui from detention one week earlier. However, there is no physical proof of his release; he has not contacted his friends or family, and his whereabouts are not publicly known. Activists suspect that he may have been moved into an apartment in Ningbo in a “non-release release” system, where an individual continues to live under the strict surveillance of security personnel and is subject to considerable constraints regarding communication and movement.

An even more murky fate has befallen Gui, who was abducted while on vacation in Thailand on October 17, 2015, and resurfaced in January 2016 when making what are believed to be forced confessions to distributing unlicensed books on the mainland and evading customs inspections. On October 24, 2017, Gui’s daughter Angela stated that the Chinese government had “released” Gui from detention one week earlier. However, there is no physical proof of his release; he has not contacted his friends or family, and his whereabouts are not publicly known. Activists suspect that he may have been moved into an apartment in Ningbo in a “non-release release” system, where an individual continues to live under the strict surveillance of security personnel and is subject to considerable constraints regarding communication and movement.

While clearly an improvement over outright incarceration, conditional release represents a subtle method of maintaining controls over the speech, association, and movement of writers who have incurred the ire of authorities. It is easy for international attention to a case to slacken once a writer is released from jail, but in order for these individuals to regain their full freedom to engage in creative expression, the pressure needs to remain on.