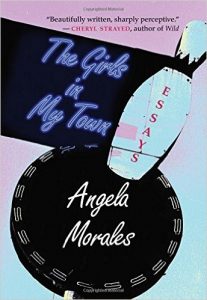

Angela Morales’s The Girls in My Town is the winner of the 2017 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay. The following is an excerpt from the essay collection.

Angela Morales’s The Girls in My Town is the winner of the 2017 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay. The following is an excerpt from the essay collection.

Submissions and nominations for the 2018 PEN Literary Awards are now open and will be accepted through August 15, 2017.

Every day, on my street, little girls push strollers with real babies in them. The girls walk with their friends—other young girls with their babies—sometimes three or four of them at a time. They walk shoulder to shoulder in the middle of the street like they belong to a fertility parade. Sometimes, we have to drive around them, swerving gently to the opposite side of the road. “Careful,” I’ll tell Patrick, as he turns the corner. “It’s a stroller brigade.” It’s an evangelist’s nightmare. (Or would that be a dream come true?).

Times have changed since my grandmother and great-grandmother (with sixteen children between them) dodged the shame of being dark and young and pregnant. Without reliable birth control, access to good schools (only the inferior “Indian Schools”), and decent jobs with decent wages, what choices did my grandmothers have? Even if girls did not have babies of their own, they often became mothers by default—by tending to younger siblings, nieces and nephews. Babies were a fact of life. The wealthy had nannies and nursemaids at their disposal. My grandmothers were these nannies.

Fast-forward a hundred years and observe the very same girls—now unfettered by husbands and tradition—now walking side by side in the middle of the street, chattering away as they adjust their babies’ juice bottles, talk on their cell phones, and half-heartedly dangle little rattles above the strollers. Unlike my grandmothers, the girls in this town have access to birth control pills, integrated schools with specialized programs, and guidance counselors who are supposed to tout the merits of college—even to the brown and black kids. The girls in my town have more choices, though some people might argue that when you’re young and poor and your own mother lives on welfare, those choices are hard to find. Love, on the other hand, is easier to find. Love (or the promise of it) is free. Love makes you feel good, especially if you’ve never had a father, even if only for a few minutes. Love is beautiful: think of walking hand-in-hand with the green-eyed Francisco at sunset along some fictional beach. And if you end up getting pregnant, We are here to support you. And here’s a fact about babies: Babies now come with many cute accessories—headband-bows for little bald heads; Lilliputian t-shirts imprinted with hip slogans like “Ladies Man” or “Change My Diaper, Biaatch!”; knit caps with built-in Mohawks and bunny ears; pacifiers with vampire fangs painted onto the mouthpiece.

V

The obstetrics nurse at Mercy Hospital dims the lights and draws the threadbare curtain across the center of the room, a flimsy illusion of privacy between me and my fourteen-year-old roommate. Both our babies had been born around midnight, and now, with babies swaddled and sleeping inside plastic, wheeled bassinets, sleep seems like a superb idea.

Everyone has gone home, and I’m alone for the first time with my newborn daughter. I can’t stop staring at her. She’d been the loudest, angriest baby in the nursery, apparently furious at having been exiled from the womb. With our bodies now separate entities, the world, to me, seems upside down. Sharp-edged. Somewhere, a car smashes into a tree. Airborne bacteria and spiky pollens float past. And who is this little human, anyway? What about her life comes predestined? I try to see the tiny, scrolled-up map inside her skull—the grid within her brain, the catalogue of her choices, and, ultimately, her destiny and desires: an aversion to crowds, a deep compassion for animals, a love of money, a penchant for mathematics, a blind left eye.

Meanwhile, my roommate and her boyfriend are lying side-by-side in bed and watching back-to-back-episodes of Cops. Crack addicts make excuses, a homeless woman sobs over a lost dog, a teenage girl’s Baby-daddy just put a steak knife to her throat. My roommate’s Baby-daddy adds his own running commentary: “Damn, look at that dude! He’s so fucked up. Hey! Remember when the cops beat the shit out of my uncle?” My roommate murmurs something in reply. And what’s going through her head? I try to remember being fourteen. I try to imagine being a mother at age fourteen.

Then my roommate’s baby starts crying. The crying gets louder. Pretty soon the baby wails like a peacock. Ay-ya! Ay-ya! Suddenly the sound of a crying baby makes me feel crazed, like an animal with its paw caught in a trap about to gnaw off its own foot. My head throbs. My spine aches. I wonder if these fourteen-year-old children know what do with an infant. Do I know what to do with an infant? How will we keep these babies alive? How will these children survive the years ahead? Jesus, where the hell are the nurses? I think. I consider saying something, but I’m too exhausted. I’ve got seventeen years on her, and compared to her, I’m already an old lady.

VI

The Lamaze teacher said, “Visualize that your uterus is a beautiful spring bud, slowly unfurling its leaves, blossoming right before your eyes.” This teacher talked so gently about the body and the birth process—how childbirth happens every single day—how women’s bodies are designed for birth. Her voice, like a drug, hypnotized me as I sat cross-legged with the other pregnant women—some with husbands, some with boyfriends, some with their moms. We breathed deeply and traced slow circles across our bellies—a technique that supposedly calms the body, calms the mind.

At the onset of my labor, then, I successfully envisioned a Georgia O’Keefe Orchid, a soft swirl of violet petals and leaves. As labor progressed and the pain intensified—surprise, surprise—my orchid melted away and in its place appeared an engulfing blackness. Eventually, as the pain intensified into lightning bolts, a creature took shape—half-man, half-goat, with horns, red eyes and lobster claws, the whole bit; he could have leapt right out of a Francisco de Goya painting. By the eighth hour, the beast had burst right through the floor and had me around the waist and was trying to pull me into the hole that had opened up in the middle of the floor.

Lying in my hospital bed in the small-town Catholic hospital, I decided to surrender myself to the image; in other words, I would not swim against the current and try to turn the demon back into an orchid. Instead, I would face my nightmare head on: I would grab that son-of-a-bitch by the horns and peer directly into his flaming eyes. Ha! Two can play at this game, I thought. Here’s what the Lamaze teachers don’t tell you about childbirth—particularly childbirth without drugs: the goal is not really to stay calm and focused; the goal is to stay alive! Once, when I was eighteen, a fortune-teller peered at my palm and said, “Mmm…lucky you live in these times. One hundred years ago you would have died giving birth.” In this small-town hospital, though, one hundred years does not seem like that long ago.

With the fortune-teller’s words echoing in my head, I told myself to fight like a warrior. Screaming felt good. I screamed until my throat became sandpaper. Suddenly, a nurse grabbed me by the wrist and said sternly, “Dear. You are wasting an awful lot of energy on all that screaming. Why don’t you get a hold of yourself? Just calm down.” I jerked my arm away and glared at her. How dare she tell me how to have a baby? How dare she intrude into my hallucination? Anyway, I thought, she had no idea what she was talking about—all those Lamaze lies, all that childbirth propaganda designed to shut us up—to keep the masses sedated so that nurses and doctors don’t get headaches.

So I decided that with each contraction I would scream every bad word I knew. Bitch, motherfucker! I didn’t care what anyone said, not Patrick, not my mother, not even the nuns. It felt good to fight, then, to unleash my rebellious tongue.

Later I wondered about my fourteen-year-old roommate who had been giving birth at the same time. Why had I not heard her voice? Did she not feel such intense pain? Had she been given an epidural? Was I too melodramatic—me with my death-defying warrior fantasy? Now I wished I’d talked to her during those two days that we shared a room. We talked a little bit, but she averted her eyes. Painfully shy. Not much of a talker. I wish I’d asked her how she got through it and whether she dreamed up some flower or some other beautiful thing. What thoughts and images travel through the mind of a fourteen-year-old girl as she becomes a mother?

This is an excerpt from the titular essay in The Girls in My Town, published by University of New Mexico Press in 2016. This essay originally appeared in the Southwest Review and in Best American Essays 2013.