This article was updated on July 24, 2020; see “ISSUE 3” below.

Well. We’re half way through 2020, and we have one or two things to talk about. Alongside the surge of protests against police violence and racism, we’re contending with the COVID-19 pandemic, an accompanying “infodemic” of disinformation and misinformation, the ever-growing spread of online hate and harassment, conspiracy theories, and a raft of bad ideas about how to fix the internet. Traffic to Facebook’s web version is up something like 25 percent, Nextdoor’s is up triple that, and all this online talk—hopeful, hateful, factual, false—is being moderated, and the systems used to do it are changing faster than ever before.

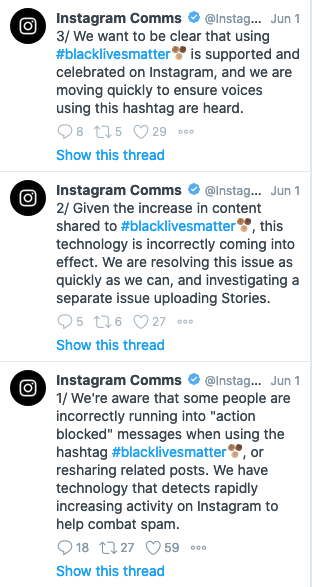

Just weeks before the worldwide shutdown, Facebook said it was going to start relying more heavily on AI for moderation, but that it wouldn’t make a noticeable difference. On June 1, Facebook apologized for the automated blocking of #blacklivesmatter posts on Instagram, to the consternation of activists and free expression advocates. On June 3, Facebook apologized for blocking #sikh for months, this time apparently due to human error. What these twin incidents tell us together is this: Whether it is in the context of the anti-racism movement or the remembrance of tragedies like the 1984 Sikh Massacre, there are some big discussions we need to have ASAP about how exactly content moderation is impacting free expression domestically and around the world.

Most social media companies rely on a mix of artificial intelligence and human beings to keep tabs on what’s being posted on their platforms and remove stuff that violates the law or terms of service. Over the past several years, a debate has raged about the appropriateness of each. Can AI work well enough to understand local dialects and slang or to distinguish satire from disinformation? How do we deal with the inevitable biases of human moderators? What’s the mental health cost on human moderators who have to look at all the worst things on the internet, day after day after day?

The companies have usually downplayed the possibility of relying too heavily on AI1A quick note on definitions. “Artificial intelligence” is a broad term that refers to a number of fairly different mathematical approaches. For this article, we’ll keep it simple and lump them together, in part for clarity and in part because the social media companies themselves very rarely publicly differentiate what approaches are in use. for content moderation. Their answer has instead been to rely heavily on human moderators, in some cases with assistance from AI to help prioritize what gets reviewed. The specifics are not very transparent, vary from platform to platform, and have evolved over time. For example, Facebook has relied on large, contracted staff working at call-center-like facilities. Reddit and Nextdoor largely outsource their moderation to channel “mods” from their user communities.

Then came the pandemic. Many platforms had to rewire their moderation systems almost overnight to confront the crisis. Facebook had to suddenly shut down entire human moderation call-center-style operations and start using a whole lot more AI. Across the board, this has meant a whole lot of novel AI. Whether it is in the form of Twitter’s experiments in automatic labeling of problematic content (or nudging users who may be readying to post some), or in the form of Facebook’s increased reliance on AI to directly remove content, the pandemic has seen not only an increased reliance on existing AI capabilities, but the deployment of new approaches and entirely new features. And those don’t appear to be going away any time soon.

So why should we care? Content moderation systems, whether they primarily depend on humans or AI, have a giant impact on our democracies and free expression: the quality of information, who is allowed to speak, and about what. COVID and the anti-racism movement create an opening to ask some big, urgent questions. The good news is that we don’t all have to become data scientists in the process. Let’s explore three issues:

1. Structural biases, both algorithmic and analog

2. The myth of global standards

3. The speed of moderation versus the speed of appeals

Issue 1: Structural bias, algorithmic and analog

“Algorithmic bias” refers to the well-documented quality of AI to reproduce human biases based on how it is trained. In short, AI is good at generalizations. For example, one might train an AI model by showing it pictures of daisies. Based on that training, the model, with more or less accuracy, could make a guess about whether any new picture you showed it was also of a daisy. But depending on the specific pictures you used to train it, the AI’s ability to guess correctly might be acutely limited in all kinds of ways. If most or all of the photos you used to train it were of daisies as seen from above, but the photo it was evaluating presented a side view, it would be less likely to guess correctly. It might similarly have trouble with fresh versus wilted flowers, buds, flowers as they appear at night versus during the day, and so on. The larger and more diverse the training set, the more likely that these issues would be lessened. But fundamentally, the model would be worse at making accurate guesses about variations or about circumstances it had seen less often.

Returning to the world of social media, work by Joy Buolamwini, Timnit Gebru, and Safiya Noble, among others, helps connect the dots. Namely: people of color, transgender and gender non-conforming people, and those whose identities subject them to multiple layers of biases—such as black women—are often underrepresented in the training data, and that underrepresentation becomes modeled and amplified by the AI that is learning from it. As a memorable WIRED headline recently said, “even the best algorithms struggle to recognize black faces equally.”

This disturbing, well-documented, and endemic problem applies whether we are talking about photos, text, or other kinds of information. One study found that AI moderation models flag content posted by African American users 1.5 times as often as others. In a world saturated with systems that use these approaches, ranging from customer support systems to predictive policing software, the results can range from microaggression to wrongful arrest. This means that the very people who already must overcome hurdles of discrimination to have their voices heard online, and who are already disproportionately likely to experience online harassment, are also the most likely to be silenced by biased content moderation mechanisms.

But lest we think human moderation is better, it’s clear that algorithmic bias is really a sibling of the biases we find in human moderation processes. Neither AI nor human moderation exists outside its structurally biased sociopolitical environment; both have repeatedly shown their own startlingly similar flaws. The question is not whether one approach or the other is biased: They both are, and they both pose risks for free expression online. There’s also little point in debating which is “more” or “less” biased.

Each process—whether manual, automated, or some combination of the two—will evince biases based on its context, design, and implementation that must be examined not just by the companies or outside experts, but by all of us. Like any system that helps shape or control free speech and political visibility, we need to be asking about each of these moderation systems: What does it do well, what does it do poorly, whom does it benefit, and whom does it punish? To know the answer to these questions, we need real transparency into how they are working and real, publicly accountable feedback loops and paths to escalate injustices.

Issue 2: The myth of global standards

So, we’ve seen that both AI and human moderation have acute limitations. But what about the sheer scale of what’s being moderated? Can a team of moderators or string of code apply standards globally and equally? In short, no.

Countries outside of the United States and Europe, those with less commonly spoken languages, and those with smaller potential market size are underserved. Marginalized communities within those countries, geometrically moreso. The largest platforms have been investing in staffing by region, and in some cases by country, but no platform has achieved the bar of even one local staff member (or contextually trained AI) to oversee content moderation for each supported language or country. The continents of Africa and Asia are particularly underserved.

It seems likely that the pandemic has made this even worse. At first glance, it might seem like AI would make it easier to provide global scale than human moderation. But AI has to be trained for each language and culture. That takes time and money. It also takes data, and large, high-quality datasets are not always available for smaller and emerging markets. What does that add up to? High-quality AI remains largely unavailable for many or most languages and cultures, let alone dialects and communities.

What does that mean during the pandemic? AI-reliant moderation being “turned on” globally means that the further you get away from Silicon Valley, there’s a higher likelihood the quality of the content moderation would have gotten worse. While data is scarce on these points, it’s hard to escape the question of how much of the world is currently effectively unmoderated on Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms. That means the potential of unchecked hate speech, overmoderation of certain communities and dissenting voices, and increased vulnerability to disinformation campaigns. Data has not been forthcoming on this from the social media companies, but we know that the Secretary General of the U.N. has cited an unchecked “tsunami of hate” globally, in particular online. The silencing of free expression by those targeted should alarm us all. As with Issue 1, it’s not necessarily that we simply want a return to the pre-pandemic way of doing things—those were bad, too. But some transparency, access to relevant data for researchers and the public, and a good honest conversation could do a world of good.

Issue 3: The speed of moderation versus the speed of appeals

Update (7/24/20): Before diving into this section, a note on piracy. Since the publication of the original version of this blog, artists rights advocates have raised the important point that content moderation discussions often fail to acknowledge the extraordinary amount of copyright infringement that is taking place on platforms like YouTube. For writers, recording artists, and others, the resulting inability to make money from their work, whether in the form of direct sales or royalties, can become the defining problem of their artistic lives and livelihoods.

The unfortunate truth is that the systemic and long-running failure to remove infringing and violative content and the failure to provide rapid, accountable appeals processes for when inevitable errors do occur, coexist and have shared roots. The platforms have chosen not to build rigorous, transparent and accountable content moderation capacities.

Both of these problems — albeit of unequal scale and disparate impact — are urgent. By focusing here on takedowns of non-violative content and the latency of appeals processes, we’re by no means denying the existence, or sheer scale, of piracy that damages the livelihoods of writers and artists, nor the need for more aggressive protection of those rights by the platforms (an issue robustly addressed by our colleagues at The Authors Guild). Instead the point is this: Takedown and appeals practices need to be held to account as well.

This section has been updated to refocus on its intended subject: the impact of downtime in the context of activism and its potential impact on public expression during urgent political moments.

***

Finally, we have the question of what happens after content is removed in error. Any way you slice it, content moderation—particularly at the scale that many companies are operating—is very, very hard. That means that some content which shouldn’t have been removed will be, and it means that the ability of users to appeal removals is critical not just for the individual, but for platforms to learn from mistakes and improve the processes over time.

It might seem reasonable to argue that because the pandemic creates increased public interest in reliable health information, we should have more tolerance for “over-moderation” of some kinds of content, in order to limit the extremity and duration of the pandemic. For example, we might be more okay than usual with jokes about “the ’rona’” getting pulled down by accident if it means that more posts telling people to drink bleach get the ax in the process. The question gets complicated pretty quickly, however, when we look a little deeper.

One of the less discussed impacts of over-moderation is down time. How long, on average, is a piece of content or account offline before it is restored, and what are the consequences of that outage? Down time is pure poison for writers, artists, and activists who are trying to build momentum for a cause or contribute to fast-moving cultural moments. Returning to the examples from Instagram at the top of this article, we can see that the restoration of access to #sikh and #blacklivesmatter and public acknowledgement of the outage, while important, did not necessarily make those communities and voices whole; in some contexts, the timeliness of the conversation is everything. The problem here is that, while the non-violative content or conversation may eventually be restored, audience and the news cycle move on. In the context of dissent, protest, and activism, latency can wound a movement.

What’s important to realize is that while the use of AI moderation has increased — including in directly removing content — appeals generally still rely on human beings, who review such appeals on a case-by-case basis. That means that moderated content that is non-violative can remain offline for hours, days, or weeks before ultimately being restored. This situation has very likely been worsened by the exigencies of the epidemic, with higher rates of mistaken removals and fewer human moderators available to process appeals. It is difficult based on available data to understand the degree of the problem, how it has been impacted by the pandemic, and which demographics are most impacted.

Facebook’s May 2020 transparency report notes that over 800,000 pieces of content were removed from Instagram under the shared Facebook/Instagram Hate Speech policy in the first three months of 2020. Of that, some 62,000 removals were appealed, and almost 13,000 were eventually restored (just under two percent). Facebook does not break down these numbers demographically. Data regarding how long restored content was down is also unavailable. Numbers during the pandemic, including at the tail end of Q1, are also incomplete or unavailable.

Given the current domestic and global political moment, what are the ramifications of this unexamined overmoderation? In a situation where various factions and organizers are trying to amplify messages, build momentum, and grapple with sensitive topics like race, sex, and religion, over-moderation of those engaging appropriately but on contentious issues becomes more likely. This poses risks for free expression that are particularly alarming in a context where such contentious but vital public debates are now necessarily happening in the virtual sphere; this was already true before the pandemic, and it is now even more so. Again, the question is not whether automated or human processes are better—the question is how specifically these systems are functioning and for whom.

Never waste a good crisis. Definitely don’t waste two.

It’s summer and the pandemic drags on, disinformation continues to spread, and authoritarian regimes are becoming ever more brazen. In the midst of all this, writers, artists, and organizers are speaking out, sharing their truths and exercising their rights, including in the historic anti-racism movement in the United States and abroad. But some are facing a head wind. Our moderation systems, and their appeals processes, will need to do better. In pretending to treat all content as equal, we have built deeply biased and politically naive systems that will continue to magnify harms and be exploited for personal and authoritarian gain.

Now is the time, as we rethink the handshake, the cheek kiss, and the social safety net, to rethink moderation. In order to do that, we need facts. How specifically are communities of color being served by these processes? Where specifically are our American technologies being appropriately tuned and staffed around the world to mitigate their harms? How will the platforms address the inevitable logjams of moderation/appeals pipelines that have AI at the front and humans plodding along at the back?

In an emergency, a lot of decisions have to get made without the usual deliberation. But as parts of the world begin to reemerge—and perhaps also face a second wave of COVID-19—and as we read headlines every day about disinformation campaigns from Russia, China, and your racist uncle with a few bucks and a botnet, there are a few big questions we need to start asking about how content moderation worked before, how it is working now, and what the plan is. November is just around the corner.

Matt Bailey serves as PEN America’s digital freedom program director, focusing on issues ranging from surveillance and disinformation, to digital inclusion that affect journalists and writers around the world.