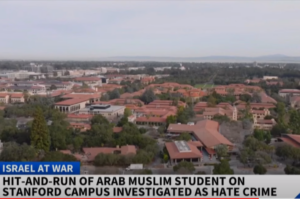

Nov 10 – In the last month a wave of anti-Muslim, anti-Arab, and anti-Palestinian incidents have occurred on college campuses in conjunction with the ongoing Israel-Hamas war, including violent attacks, threats, and targeted, hateful and menacing rhetoric. At Stanford University, a driver targeted an Arab Muslim student in a hit-and-run that authorities are investigating as a hate crime. At American University, where administrators have noted a rise in Islamophobia on campus, a note saying “GO BACK WHERE YOU CAME FROM” and “DEATH TO ALL PALESTINIANS!” was found under a Palestinian’s staff member’s office. A similar set of messages was written at Yale University on a whiteboard outside a dorm room.

At Princeton University, a staff member stole a student’s phone and grabbed their hair at an off campus protest and also compared all pro-Palestinian protestors to Hamas. At the George Washington University, students have reported their hijabs being ripped off, while at Vanderbilt University, Muslim students have reported being called “terrorists” and feeling physically unsafe on campus. In campuses across Georgia, “Palestine-specific incidents of Islamophobia” are on the rise, with students reporting they are experiencing hate simply because of their identities.

In addition to targeted incidents, it is important to note that institutional support for Palestinian, Muslim, and Arab students has varied. On some campuses Arab and Muslim students report feeling insufficiently supported by administrators, who may have condemned Islamophobia on their campuses but have not, for example, created task forces or other efforts to support their students and, more broadly, have failed to treat Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism with equal weight to other forms of hate on their campuses.

Contextually, it is critical to understand that students who appear to be Arab are often presumed to be Muslim and are being targeted by hateful acts as a result, when in fact their identity and/or religiosity may differ; for this reason, Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism are often difficult to disentangle. It is also critical that college and university administrators understand that for many Muslim and Arab students, the post-9/11 surveillance and censorship of their communities looms large and creates additional fears of being targeted. This concern extends to international students as well, who, due to recent charged rhetoric from public figures, may fear jeopardizing their visa status if they participate in pro-Palestinian protests or criticize the Israeli government’s response to the October 7 Hamas attack. Other students have been doxxed by outside groups in response to their speech critical of Israel, on numerous campuses.

As an organization dedicated to the protection of free speech, PEN America is well aware of how the spread of hatred can impair open discourse and poison a healthy learning environment. Amid an increasingly menacing climate, campus leaders have an obligation to be responsive to threats, intimidation, and students’ encounters with overt Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism, and to ensure that they address students’ concerns through approaches that adhere to laws and campus policies protecting academic freedom and free speech. Assertive campus leadership is imperative to nurturing a learning environment where all feel welcomed and fully free to participate in the exchange of ideas and opinions, without fear. In a time of increased incidents of hateful speech and hate crimes both nationally and around the world, the potency of individual instances of hateful speech on campus can be heightened, increasing the psychological harm that such speech can cause and underscoring the imperative of effective institutional responses.

We encourage campus leaders to consult PEN America’s Advice on Responding to Hateful Speech on Campus. Essential steps include:

- Speak Out. Campus leaders should work to dispel hatred, including by unequivocally condemning Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism on campus when it arises. Effective responses can include counter-messaging, condemnations, and offering direct support and empathy to targeted individuals and groups. In messages sent out to the campus community or shared on public platforms, leaders can propound core values as essential pillars of campus life, such as inclusion, tolerance, and mutual respect. Speaking out includes actively exposing and debunking or rebutting Islamophobic stereotypes and rhetoric—for example, that “Muslims are terrorists” or that all Muslims are foreigners.

- Educate. Universities are natural settings for fostering education. Administrators should endeavor to hold teach-ins and to support faculty experts who can educate the community about the history of Palestine, the conflation of Muslim, Arab, Middle Eastern, and South Asian identities, Islamophobic rhetoric and tropes, and the nuances of pro-Palestinian advocacy. Campus leaders must also explain that hateful speech that is intended to menace, intimidate or discriminate against an individual based upon a personal characteristic or membership in a group can impair the university’s obligation to provide equal access to the full benefits of a college education and the ability of all students to participate in campus discourse.

- Defend. Just because speech is offensive does not mean it is impermissible, much less unlawful. Universities must hold open the space for heated debate, disagreement and the expression of distasteful views. The Israel-Hamas conflict is a matter of public concern, and an appropriate topic for debate and protest on campus. Where speech falls within the bounds of campus policies and First Amendment protection, campuses must resist demands to ban or punish it, doubling down on alternative measures that help affected students feel protected, supported and heard.

- Secure. Campuses have an obligation to ensure the physical security of students, faculty and staff. Visible enhanced security measures can both deter unlawful and inappropriate behaviors and help foster a sense of security for the vulnerable. At the same time, administrators should be mindful that an increased police presence may contribute to feeling unsafe for students from some marginalized groups.

- Support. Campus leaders should prioritize providing solidarity and resources to affected students including visible gestures of institutional support and increased access to mental health practitioners as needed. They should redouble efforts to ensure students can readily access these resources and services on campus. They must also clarify and publicize their policies related to the free speech of international students.

- Guide. Campus discourse should be predicated on the presumption of respect for differences, including differences of view that cause disagreement. Campus leaders can review how they are facilitating a climate for open and respectful exchange, through trainings for faculty, staff and students. They can establish or reiterate policies on protest rights that welcome the airing of strong views, but do not condone the intimidation or silencing of others. In order to live together on a diverse campus, university constituents need to be aware of what may cause offense and why, and to carefully consider ways to avoid such words and actions, even if no offense is intended.

- Investigate and Hold Accountable. When speech crosses the line into hate crimes, true threats, harassment, and any other conduct that violates the law, prompt investigation and accountability measures are essential, including the engagement of law enforcement and criminal referrals where appropriate. That said, campuses must avoid appearing to suggest that protected speech and expression might cross the line into criminality.

Additional Resources for Understanding Islamophobia