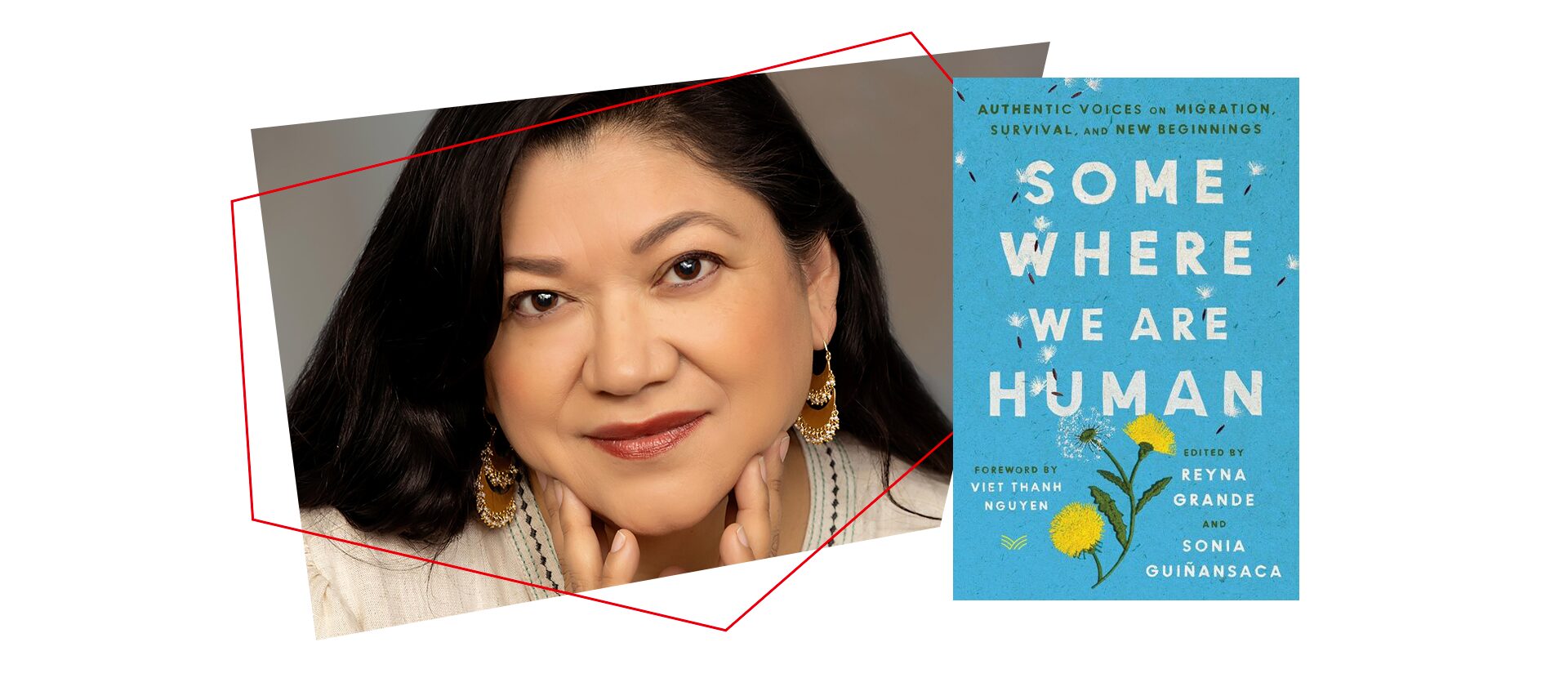

Reyna Grande | Member Spotlight

Author Reyna Grande’s journey as a Mexican immigrant and first-generation college graduate is a story of resilience, reclamation, and empowerment. Grande, born in Iguala, Guerrero, Mexico, and raised in Los Angeles after crossing the border as a child, has become one of the most celebrated voices in contemporary American literature. Her memoir A Dream Called Home was recently named one of the best books of the 21st century so far by Kirkus Reviews, illuminating themes of identity, belonging, and perseverance.

Grande spoke with Ariha Shahed and Awakhiwe Ndlovu, interning with Membership & National Engagement at PEN America this summer 2025, to reflect on her journey as a writer, her creative process, and the political and personal landscapes that shape her work, with the hope of inspiring others—especially immigrant and BIPOC communities.

We’re so honored to celebrate your recent recognition by Kirkus Reviews. What made you decide to pursue writing professionally? Was there an “aha” moment that sparked this passion for you?

I had my ‘aha’ moment when I was a student at Pasadena City College. I was 18 going on 19 and took an English class with Professor Diana Savas. She talked to me about the possibility of pursuing a major in creative writing and also getting a university degree. She introduced me to Chicana and Latina authors like Sandra Cisneros and Julia Alvarez. She put The House on Mango Street in my hands and said, “If Sandra Cisneros can do it, you can do it.” It was thanks to my teacher that I started to dream of becoming a professional storyteller. I’m eternally grateful for her encouragement because she saw my potential before I could see it in myself. She helped me believe that my stories mattered and that I had something to contribute to this world through my writing. She put me on the path towards becoming a storyteller. Teachers have the power to destroy you or to build you up. To give you wings and encourage you to take flight. And I am who I am now thanks to my English teacher.

Those of us who have been able to meet the kinds of teachers that are passionate about their students and about making a difference are really fortunate. We have reached a level of success because we had either a great teacher or mentor that helped us to get to where we are.

You’ve spoken about your journey of reclaiming your narrative as an immigrant through writing or art. How would you describe that experience?

Writing has been essential in reframing my experiences as an immigrant. I was very young when I came to the U.S. and had been separated from my parents for years. I didn’t understand why my dream, my desire to reunite with my family could be seen as a crime, even as a child who knew nothing about immigration policy. Being here and coming of age in this country was very difficult for me as an immigrant, brown, and Spanish speaking kid.

I internalized that racism. I started to be ashamed of being a border-crosser. But when I met my teacher at Pasadena City College and began writing my story, I started to see that these experiences were not burdens—they were gifts. She taught me to celebrate who I am.

I want to keep telling and archiving the stories of my community, to lean into wonder and curiosity, and to create work that transcends borders—physical, emotional, and cultural. Being a ‘border-crosser’, I have known how to break down barriers, how to survive separation and displacement, since childhood. I want to ensure that our experiences are documented, celebrated, and passed down for generations to come. My goal is to honor the lives and journeys of immigrants and marginalized communities through my writing, and writing allows me to show the world that we exist beyond the borders and censorship imposed on us, and that in itself is both an honor and a responsibility.

Being a ‘border-crosser’, I have known how to break down barriers, how to survive separation and displacement, since childhood. I want to ensure that our experiences are documented, celebrated, and passed down for generations to come.

In your memoir A Dream Called Home, there are tensions between themes of belonging and alienation. How did this divide affect your experience as a writer on a college campus specifically, especially during such a formative period of your life?

A Dream Called Home is a memoir about my experiences as a first generation university student and transfer student. Being a first-gen is something that many of our communities experience and it can be quite a lonely, scary experience. But it’s also important because we’re making history in our families, we’re breaking cycles.

I’m grateful for those two and a half years that I spent at my community college because once I got to university, I felt a lot more prepared for university life. I wanted to celebrate that experience because community college can be such a great place for us to grow, mature, and learn how to be college students.

It was challenging when I went to UC Santa Cruz because I was coming from Los Angeles where I had experienced a lot of diversity. I was comfortable in those places. When I got to UC Santa Cruz, the Latino student body was small. I experienced a lot of culture shock and alienation.

I was very scared to take up space when I felt that I didn’t belong there. As hard as it was, I am very grateful for those experiences because it really taught me how to step out of my comfort zone. It taught me how to be more proactive and build community. It taught me the reality of the world, because in the real world, there are going to be so many moments where I’m going to be made to feel that I don’t belong there, that I shouldn’t be there. This experience that I had in Santa Cruz taught me how to advocate for myself and to take up space. I overcame insecurity and impostor syndrome.

Once I graduated, I went out into the world fighting for my stories, for my dreams, to take up space and deal with all the micro and macro aggressions out there.

Your writing explores the longing for “a home that would endure”. If you could distill ‘home’ into an idea or essence, what would it be for you?

To me, home is not a place on a map, it’s something that you have to build and create for yourself and can take with you wherever you go. It’s learning how to be a turtle and carry your home on your back — to get rid of an ‘emotional homelessness’ and nostalgia. It has been really important to see home that way because as an immigrant one of the first casualties of immigration is our home. We lose homeland, community, culture, and connection with our loved ones.

It’s important for us to reframe home as something that is not necessarily a place on a map, but as something that we can create through our continued celebration of our culture. I created a home through the family I have built for myself–husband, children, friendships, and my community. It helped me get rid of this feeling of being uprooted and transplanted into toxic soil when I arrived in the U.S. And now I feel more grounded.

I have now created a home for myself where I feel that I belong, where I am loved, where I am accepted for who I am. That has really protected me against all that’s happening in the world and in our country right now.

You weave historical events—such as the Mexican-American War—into A Ballad of Love and Glory and your body of work. Can you speak to the importance of engaging with history as an essential part of literature?

When I wrote A Ballad of Love and Glory, I wanted to teach myself the history that I was not taught in my K-12 education. In my novel I explored the creation of the U.S.-Mexico border as we know it today. I write about the U.S. invasion of Mexico in 1846 that led to the U.S. stealing half of Mexico’s territory. I really wanted to push back against this romanticized idea of the United States and its Manifest Destiny. Against the myth of its creation and bringing to light Mexico being a victim of U.S. imperialism and greed.

So many people in the United States have no awareness of that history because they aren’t taught about it in schools. Mexican-Americans have been oppressed throughout the centuries and erased from history books. This has caused so much damage to the community.

Our history does not teach us that the Mexican community has been here even before the United States was the United States. Our communities are indigenous to these lands and yet in this rhetoric that has been sculpted — we continue to hear — Mexicans are the outsiders and invaders. I want to continue to look at other time periods in U.S. history where we have been erased and left out. I want to try to bring it back into our collective consciousness and to make it part of the conversation.

To me, home is not a place on a map, it’s something that you have to build and create for yourself and can take with you wherever you go. It’s learning how to be a turtle and carry your home on your back — to get rid of an ‘emotional homelessness’ and nostalgia.

A prominent quote in your anthology, Somewhere We Are Human, you write — “We hope you join us in finding a home together as we pursue a future not defined by borders” — calling for a future without borders. As a Mexican-American, how do you personally process the immigration policies by the current government, given that large-scale deportations also occurred under prior administrations?

In the anthology Somewhere We Are Human, you can see that one of our collective longings and dreams is to try to create a world where we can remove these borders and barriers that divide us. We’re collectively striving towards creating a more just world where we can celebrate and acknowledge our shared humanity.

Right now we’re living through a time where our communities of color are being terrorized and living in a constant state of vigilance, fear, and anxiety. One of the most disappointing things is that every administration has in some way continued to terrorize immigrant communities of color. What we see today has been done before. The violence being perpetrated on our communities of color is not new, it’s been happening since the very beginning. Immigration policy has been very racist and discriminating against communities of color.

This attack has been a collective effort by both Democrats and Republicans. They have instituted racist immigration policies and both have taken turns building the wall. It is very disheartening for me because I keep hoping for political leaders that can implement humane immigration policies — they can finally overcome these phobias of our communities and recognize what we contribute and everything that we have to offer.

If you look at the mass deportations that are happening right now, we saw it in the 1930s, 1950s and we’ve seen other communities too face a lot of discrimination and terror. Detention centers, like Japanese Internment camps seen in the past, have been built and families have been separated before.

It’s essential that we learn from our history and start doing things differently so that we don’t continue to repeat all these horrors. I have a lot of hope that even in the darkest of times, our communities do come together and we try to overcome them. We offer each other hope, strength and resilience. If we continue to work together to dismantle the systems of oppression, we will be victorious and will eventually create a more just world.

Is there anything you’d like to say to PEN America’s audience— many of whom stand to protect free expression and human rights? How can we honor the people in your writings, in the anthology, not just with empathy but with action?

It’s important that we continue to support immigrant voices and voices of color. We need to read their books, support them, and amplify their voices. It’s important to collaborate with other groups and nonprofits that are working hard, for immigrant rights and for human rights. PEN America can continue to defend free expression, and make sure that we all are being heard. We all have a voice, but not all are being heard.

It’s important for us to use our resources, to use our platform, to use everything that we can to make sure that other voices that have gone unheard can now take center stage.

It’s essential that we learn from our history and start doing things differently so that we don’t continue to repeat all these horrors. I have a lot of hope that even in the darkest of times, our communities do come together and we try to overcome them.

What advice would you give to young writers looking to combine their passions of advocacy and literature?

“The way that you see the world is very unique. Only you can tell the stories. Nobody else can tell them the way you can”

We all could write about the same theme or topic, but everybody is writing it through our own unique lens, which is our strength. Make sure you embrace your unique voice and celebrate that. The way that you see the world is very unique. Only you can tell the stories. Nobody else can tell them the way you can.

Something to remember is that, through stories, you are building bridges that connect us as a community and make us strong. The stories you share are really important because they matter now, but also for generations to come.

“It’s important to not overburden yourself. It’s a big fight we’re fighting.”

You don’t have to be at every protest or write about every issue. Don’t burn out, learn to pace yourself, and give yourself some self-care. It’s important to not overburden yourself. It’s a big fight we’re fighting.

We’re working collectively as a community, and whenever you need a little rest to recover, don’t feel guilty about that. We’re in it for the long haul, we’re doing this together, and we have your back.

Reyna Grande is an acclaimed Mexican-American author whose work powerfully explores themes of immigration, family separation, and the pursuit of the American Dream. Her memoirs The Distance Between Us (2012) and A Dream Called Home (2018), named one of Kirkus Reviews’ “Best Books of the 21st Century (so far)” in 2025, illuminate the realities of undocumented childhood immigration from Mexico to the United States. Grande is also the author of several novels, including Across a Hundred Mountains (2006), Dancing with Butterflies (2009), and A Ballad of Love and Glory (2022), a historical epic set during the Mexican-American War. She adapted The Distance Between Us as a Young Reader’s Edition and co-edited Somewhere We Are Human: Authentic Voices on Migration, Survival and New Beginnings (2022), amplifying undocumented voices. She has received numerous honors, including the American Book Award, the Poets & Writers “Writers for Writers” Award, and recognition as a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Awards. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, CNN, and The Washington Post.