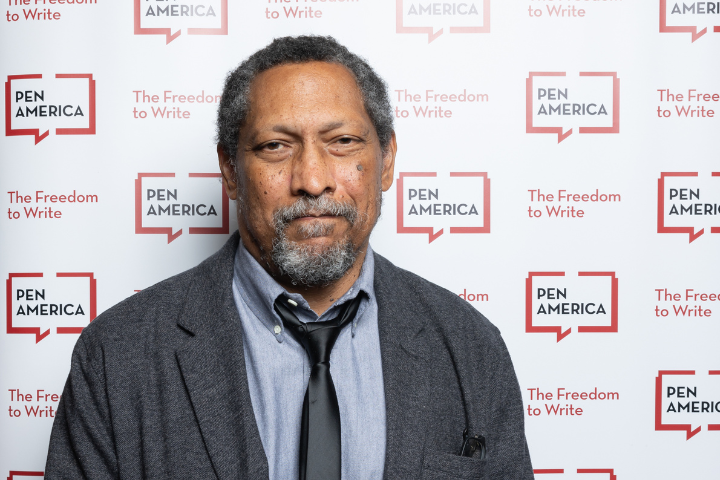

Hokeah Was One of Two Writers of Native Heritage to Receive Book Prizes at the 2023 PEN America Literary Awards Ceremony

By Suzanne Trimel

(NEW YORK)— Oscar Hokeah writes fiction grounded in his own life experience in Oklahoma as a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and the Kiowa Tribe on his mother’s side and of Mexican heritage on his father’s. His writing also is rooted in the real life trauma, suffering and healing he has witnessed directly working for decades with at-risk youth among the Native population.

Raised in Tahlequah and Lawton, Oklahoma, Hokeah’s first novel, Calling for a Blanket Dance, this month won the PEN/Hemingway Prize for Debut Fiction. Through the years, the prize has signaled exceptional talent to readers of literary fiction, from Teju Cole and Ha Jin to Chang-Rae Lee and Jhumpa Lahiri.

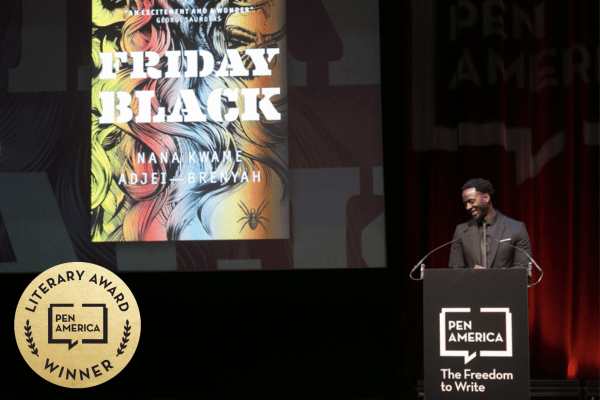

Hokeah was one of two writers of Native heritage who received prizes at the PEN America Literary Awards ceremony on Mar. 2. Morgan Talty, also of Native descent, won the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Short Story Collection for Night of the Living Rez. Other writers of Native heritage—novelist Ramona Emerson, poet dg nanouk opik and translator Lynette Yetter—were among the 2023 PEN America finalists, which attests to a literary renaissance. Hokeah said: “I do feel like it’s a new Native American renaissance and it’s become more mainstream to engage with Native authors and our writing… with a critical eye and compassion.”

Tommy Orange, a writer of Native heritage and also a PEN/Hemingway winner in 2019 for his debut novel There There, praised Calling for a Blanket Dance as “vital and powerful” in an article in Lit Hub titled “88 Writers on the Books They Loved in 2022.”

Hokeah has written short fiction for decades, with stories published in South Dakota Review, American Short Fiction, Yellow Medicine Review, Surreal South, and Red Ink Magazine, among others.

“My work is very much grounded in the very real experiences of Indigenous daily life,” he wrote in an email exchange with PEN America. “Because I draw from lived experience, whether my own or friends and family, my writing reflects hardships and triumphs that many Native Americans face today. It’s a modern representation of Native circumstances directly from historically targeted communities.”

His novel is a multi-generational family saga centered around Ever Geimausaddle, a man of Mexican and Kiowa-Cherokee heritage whose story is told through the perspectives of different family members who have watched him grow up, each recounting a decisive moment in his life. The voices of different narrators are captured in each chapter and those points of view are bound together—like the threads of a blanket— by love for community, tradition, and centuries of injustice.

Ever’s ancestors pass down knowledge, tradition, and values that ground him and offer resilience and ultimately, salvation. The book extends a poignant reminder of a universal truth—that community and family are where we gather strength to face life’s crises and challenges.

The opening pages jolt readers with a violent injury to Ever’s father, at the hands of police. The story moves to his mother, who struggles to hold on to her job and care for her husband. The family is constantly moving. All of this— along with the legacy of centuries of injustice— leads to Ever’s bottled-up rage. Meantime, his relatives offer their ideas about who he is and who he should be.

The book’s title comes from a Native tradition. Blanket dances are held to honor or help individuals or groups. A blanket is carried around the circle or sometimes placed in the circle. Donations are gathered in the blanket.

Hokeah’s powerful prose delivers a rich blend of Native American phrases and words, perhaps still unfamiliar to most readers but promising to become more familiar, with the emerging renaissance of Indigenous literature and portrayals in popular culture such as the television shows Reservation Dogs and Rutherford Falls.

Of note, Hokeah has said: “I don’t talk much. I’m more of a listener.”

“It’s given me the opportunity to pick up on the nuanced speaking patterns I grew up around. It also gives me the opportunity to listen for story,” he wrote to PEN America.

While some writers are bothered being labeled and explicitly connected to their racial or ethnic identity, Hokeah is not. “I don’t mind either way. Folks can call me a Native writer, or a writer. I tend to spend my mental energy on writing books rather than battling over terminology. There is a specific Native experience that I’ve lived and my family and friends have lived from inside historically targeted tribal communities, so I don’t mind being called a Native writer because the ‘label’ honors the very real and tangible experiences that Natives have.”

Hokeah has worked for nearly two decades among youth in Native communities, including in New Mexico among the Pueblo, Apache and Diné peoples. Currently, he lives in his hometown, Tahlequah, and works with Indian Child Welfare.

Of his dedication to Native youth, he wrote that his work has allowed him to “witness healing strength in the face of tremendous adversity on a daily basis. Witnessing the many tribal members inside the community dedicating their lives to the betterment of Indigenous peoples gives me great hope. There are many everyday heroes doing powerful work inside tribal communities. It’s a blessing to watch them lead and overcome obstacles.”

A graduate of the Institute of American Indian Arts, Hokeah also studied English and Native American literature at the University of Oklahoma, where he earned a master’s degree. He points to a diverse cast of writers who have influenced him—Alice Munro, Gabriel Garcia Marquez and N. Scott Momaday, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Kiowa author—and considers the blending of cultures to be at the core of his work.

“Blending cultures is a part of my everyday experience and that transfers into my writing. It’s left me open to engaging with work across genres and communities,” he wrote, adding “it’s a very American trait to see the world through a multicultural lens, and I think it’s fast becoming more of a modern global phenomenon as well. More and more communities are becoming blended across the planet. Because of that I feel like my writing gives readers an opportunity for validation as they learn about the multicultural experiences from the characters in my writing.”

He has noted in interviews the impact of Oklahoma’s diverse communities on his writing, with 39 different Native tribes, and sizeable populations of Black and Hispanic people. “Over the last half-century, there have been a large number of migrants coming from Mexico,” he has said, including his relatives.

Readers likely will not have to wait long for a second book by Hokeah, who recently submitted a draft of a second novel to his editor. “I’m waiting for a reply if she’s going to approve it to move forward, or if I’ll need to turn in a different book,” he said. “I’ve written the first draft of a third book as a backup. I also have the outline and summary for a fourth book and am aiming to complete the first draft some time this year.”