The PEN Ten: An Interview with Francesco Pacifico

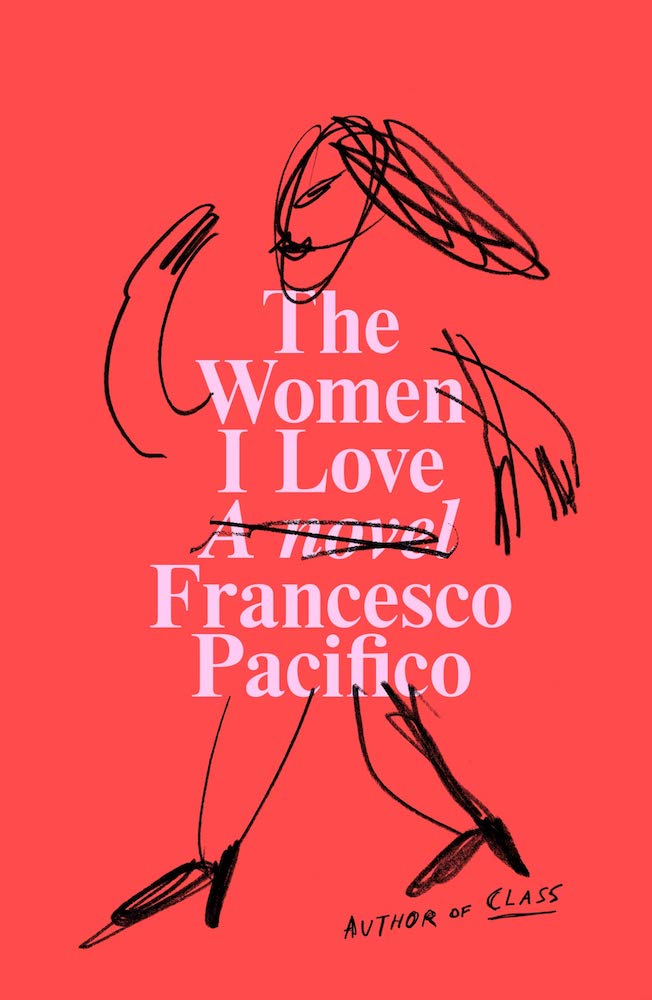

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Francesco Pacifico, author of The Women I Love (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021) – Amazon, Bookshop.

Photo by Musacchio & Ianniello

1. What is your relationship to place and story? Are there specific places you keep going back to in your writing?

Place comes first. It reveals so much about urban planning, architecture, decor, and all the social hierarchies. Story is usually more sentimental; I find it tends to redeem the wrong people—the people who are suspiciously eager to be redeemed. . .

2. What was one of the most surprising things you learned in writing your book?

It was actually the subject matter. The whole book is the discovery of my inability to describe my wife in a book. And the more general discovery, due to my upbringing, was that it was hard, overall, to let the women in my book be free from any ancillary role. Ancillary comes from the Italian word ancella (a kind of slave), so its etymology takes on a literal sense.

“The stuff we’re complicit in—it’s terrifying in real life. In literature, we have the unreliable narrator and the ‘straniamento.’ You find you’re the villain or the evil presence in a Shelley Jackson story. We’re lost like Nazis at the end of the war. I don’t want to mute that feeling.”

3. What advice would you give to a writer who is trying to publish their book—not just in general, but especially in this current climate?

I understand publishing has changed a lot since I got my start. I don’t feel like I know enough. What I know is that the context of good literary magazines creates atmosphere and provides oxygen that publishers won’t, so people who write because they love books and literary experiments should hang out in a scene among and write for those magazines.

4. What’s something about your writing habits that has changed over time?

They change constantly. Different things that transpire in your life require different approaches. Sometimes you know the names of what you’re attempting to write, sometimes you ignore them and have to hunt for them. When writing a book, there are times when you need to have a schedule and others when you need to feel free.

5. What do you read (or not read) when you’re writing?

For every book I write, there are a couple of books that stay with me for courage and reference. But they change over the course of the writing process, as if I were adding layers with time.

“I find a lot of existential possibility in being wrong and in losing. So, I don’t have messages to get across, but I enjoy reading reviews by male critics where they freak out because I’m not setting good examples.”

6. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

I enjoy putting good movies on sometimes when I’m writing, so as to remind myself of the role of gesture in human interactions. I get most of the gestalt from specific authors that are important to me (Witold Gombrowicz, Virginia Woolf, Don DeLillo, Luigi Pirandello, but there are many more), but I will sometimes be attracted to a director, too. Something I’m finishing now has been dominated by the fact that my wife and I only watched Alfred Hitchcock movies during the lockdown in the spring of 2020. As for music, it’s mostly ambient music that helps me come to terms with the crucial hollowness writing must possess.

7. Why do you think people need stories?

To contrast other people’s stories, maybe?

8. The Women I Love is described to be “a provocative and bracing send-up of modern masculinity.” What was the impetus for starting this novel, and what did you hope to get across to readers about masculinity today?

8. The Women I Love is described to be “a provocative and bracing send-up of modern masculinity.” What was the impetus for starting this novel, and what did you hope to get across to readers about masculinity today?

The new feminist wave has made me feel the thrill of finding out I might have been a sort of Nazi officer all my life without knowing it. I’m not joking. The stuff we’re complicit in—it’s terrifying in real life. In literature, we have the unreliable narrator and the “straniamento.” You find you’re the villain or the evil presence in a Shelley Jackson story. We’re lost like Nazis at the end of the war. I don’t want to mute that feeling. I don’t want to be a simp. I want my wife to erase me, to write a different story.

My first favorite author as a kid was Luigi Pirandello, whose work is all about the male crisis of identity in the modern age. That left an impression on me . I find a lot of existential possibility in being wrong and in losing. So, I don’t have messages to get across, but I enjoy reading reviews by male critics where they freak out because I’m not setting good examples. Lasciva nobis pagina, vita proba. I believe in the David Lynch approach of putting all the evil in the work to sort of purify the life.

“Maybe we can talk of the role of the writers, plural. Plural writing can tell a complex story of different reactions: a web of interconnected experiences and approaches. I feel like my story is so warped. I can only write about a void that I can’t fill. There’s no one writer whose voice is needed. Everything acquires sense in the context and with dialogue.”

9. In January, you wrote a “breakup letter to your writing career,” which was published in n+1. You wrote, “The very fact that a writer might be so discombobulated by the pandemic that they don’t know what connection even is anymore, because the reality of that connection is changing every month—this makes you mad. You want us to be steady and reliable even at moments like this one.” What’s something you learned about the role of the writer during a crisis? What takeaways, if any, have you developed about your writing career in the nearly one year since you penned that piece

Maybe we can talk of the role of the writers, plural. Plural writing can tell a complex story of different reactions: a web of interconnected experiences and approaches. I feel like my story is so warped. I can only write about a void that I can’t fill. There’s no one writer whose voice is needed. Everything acquires sense in the context and with dialogue.

10. What is something that has surprised you about getting your book translated for a new audience of readers? Does preparing for your English-language release feel different than when your book came out in Italian?

It is very different. America’s philosophical mindset is that everything is driven by the need for solutions. If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem. I feel that sometimes this very fair approach is hindered by the fact that it gets taken too literally.

Let’s take the subject matter of my novel. Detailed descriptions are always a part of the solution. Trials always revolve around trying to describe what happened. Here, though, I see that a solution is required while you’re still gathering proof. I wrote a book about being guilty, and it took a lot of patience and care to put the unflattering details on the page. But if I don’t show a fast solution, then I’m a part of the problem. I hate this mindset. We’ve kept women as slaves forever with the subtlest tricks. How can we just make peace and move on?

Francesco Pacifico lives in Rome. He is the author of the novels The Story of My Purity and Class, a New York Times Critics’ Top Book of 2017. He is a frequent contributor to la Repubblica and n+1, and his work has also appeared in McSweeney’s, The White Review, and elsewhere. He is a founder and senior editor of the literary magazine Il Tascabile. He has translated the work of a number of writers, including F. Scott Fitzgerald, Kurt Vonnegut, Henry Miller, Dave Eggers, Hanya Yanagihara, Ralph Ellison, Chris Ware, Matt Groening, David Mazzucchelli, and Alison Bechdel. His latest book in Italian is Io e Clarissa Dalloway, a meditation on the work of Virginia Woolf.