The PEN Ten: An Interview with Christopher Gonzalez

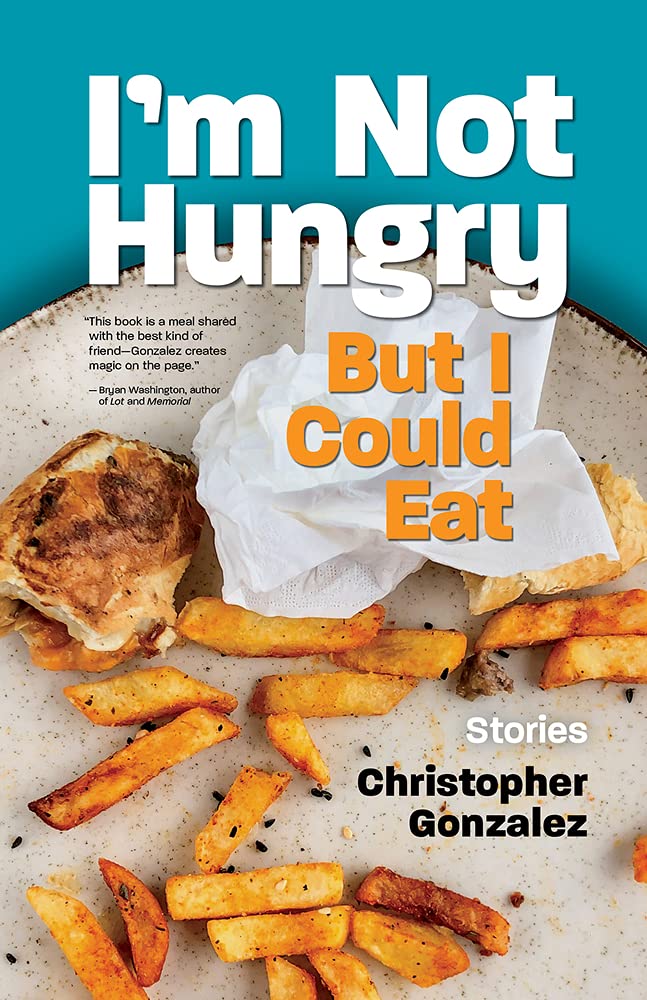

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Christopher Gonzalez, author of I’m Not Hungry But I Could Eat (Santa Fe Writer’s Project, 2021) – Amazon, Bookshop.

1. What is something that you feel your readers would find surprising about you?

1. What is something that you feel your readers would find surprising about you?

Sometimes I will order the salad instead of fries. But only sometimes.

2. There are a lot of phases to publishing a book that not everybody knows about. Which would you say was the most challenging for you?

This two-month lead-up to publication has wreaked havoc on my mental state in a way I hadn’t anticipated! (I’m good, I swear.) The funny thing is, everything I can’t stop thinking about—am I doing enough for the book, am I doing too little, am I not being enough of a go-getter?—isn’t some weird, shameful secret. I’m not embarrassed or alone.

So many writers are open about this in-between stage in the process, both online and in my own circle, but I guess I wasn’t ready to experience it myself. The book is done, I can’t change anything about it, it will be what it will be, and there is a finite amount of time and energy I can realistically devote to promoting and stumping for it. The hardest part for me has been figuring out what I can do that is something I also actually want to do, rather than committing to anything I think I should do, if that makes sense. I don’t think I’ve nailed it—but, god, I’m thankful for all the friends who’ve kept me sane as I’ve tried.

“I guess I wasn’t consciously thinking about writing younger queer people as much as I was just writing about myself and my friends. To that end, yes, my characters will grow with me. Fiction is the tool through which I am constantly reexamining my own existence. Maybe that’s selfish, but it’s the only way I know how to be.”

3. What’s the worst piece of advice you’ve ever received on writing?

One of my writing professors in college told us we should avoid thinking too much about the story or novel or whatever it is we’re writing when we’re not actively writing it. He said it would disturb the “dream.” But the problem is I live in my head, and that time away from the page is so crucial for my fiction writing. I need time to daydream and revise and spin out ideas that don’t exist in any tangible way. Maybe his advice wasn’t terrible, because it clearly worked for him. But that’s what is so terrible about a lot of writing advice—this idea that we can apply what works for one to everyone’s practice.

4. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

Louis Sachar. Just to say thank you for the absurdity, thank you for everything.

5. What do you read (or not read) when you’re writing?

I’m constantly looking to other works for inspiration. I’ll reread a favorite short story or a poem, or I’ll leaf through a novel and go back to my favorite passages. I try to remind myself what it is I love about reading and use that as fuel for my own writing. Reading has become so much harder during the pandemic though, so if something holds my interest, I’m not too precious about how similar or different it is from whatever I’m working on at the moment.

“I’ve spent years writing and reading flash fiction where the economy of words creates a negative space around a story. What is left off the page is as important as what is included. Knowing your characters and letting them sink into their own feelings, I think, allows you to go deeper faster, and—I hope, if I’m doing my job correctly—then the silences will capture that feeling of emptiness but won’t be empty themselves.”

6. What do you like to eat when you’re writing? Conversely, is there a food you now avoid because of some circumstantial conditioned taste aversion?

Eating for me is its own ritual, which is to say I’m either doing it frantically at my desk or quite sloppily in bed, while watching TikToks or YouTube videos. I don’t write and eat at the same time anymore, not really. I will have a beer or wine or some bourbon, if it’s late. I’ll have a lofi playlist going.

I used to absentmindedly eat pork rinds or Doritos while writing, and years ago I would go to a diner and get some kind of burger or sandwich with fries to have while writing longhand, which is something I can’t even imagine doing anymore (the longhand, not the diner order). I think the food becomes too much of a distraction, and I don’t lack for those when writing, so for me it’s better to eat and reset away from the page rather than fail at multitasking.

7. How did the idea for I’m Not Hungry But I Could Eat come to be? When was the moment you realized that it would have to become a story collection?

7. How did the idea for I’m Not Hungry But I Could Eat come to be? When was the moment you realized that it would have to become a story collection?

I wrote all the stories in the collection over five years, but it wasn’t until about three years into writing and publishing that I realized I was working toward a collection. It might have been around the time I wrote the story “Here’s the Situation” that I had an aha moment, and I thought, “OK, so these are the themes I’m interested in, these are my obsessions.”

Having that kind of clarity helped with writing the final pieces in the collection, because the writing didn’t feel so aimless—I had a sense of purpose and intentionality. And when I first conceived of the collection, I thought it was going to center around friendships, specifically between men—which is still there in the final book—but ultimately I was interested in exploring insatiable desire and longing and the way we downplay our own needs to make room for the attention of others. Understanding that allowed me to write the titular story, and then it felt like the collection had a shape.

8. Many of your characters in your collection are young adults—in the “prime of their life,” some might say. Yet so many of them feel lonely, adrift, or like they have to hide parts of themselves from others. This is especially true for your characters who identify as queer. Why was it important for you to write about the experiences of queer people—especially younger queer people? Do you think that over time your characters will age with you?

Lately, I’ve been thinking about this collection as a love letter to my twenties. The insecurities, loneliness, feeling adrift—all these things have shaped my life. I don’t think one is really allowed to express such feelings out loud. Not repeatedly, anyway, because eventually people expect you to change your circumstances, right? I wanted to make room for that kind of frustration on the page.

Also, I came out as bisexual after college to friends and in my mid-twenties to family, and I’m intrigued by what being “out” looks like from one person to another. I’m fascinated by what new joys and pains are made available when you finally open yourself up to your own truth. There are common hurts, and then there is such a wide variety of experiences one can have in dating and love and building community. So I guess I wasn’t consciously thinking about writing younger queer people as much as I was just writing about myself and my friends. To that end, yes, my characters will grow with me. Fiction is the tool through which I am constantly reexamining my own existence. Maybe that’s selfish, but it’s the only way I know how to be.

“I’m always drawn to writing by other queer authors of color, whether they’re writing about joy or anger or quiet narratives or love or sex or food or popular culture or anything, really. More of all of that.”

9. Throughout the collection, you explore a host of difficult and ambiguous relationships where there’s a lot unsaid between distant friends, almost-lovers, strained siblings that take their tension to the grave. In these relationships, the silence often rings louder than the actual conversations, which are repressed and stiff with an air of obligation. It’s much easier to write about what is there, what is said—but how do you go about writing emptiness, silence, hunger?

I suppose the honest answer is I have a lifetime of holding grudges and living in resentments. Not healthy at all, but I think it’s influenced my writing and how I approach each story from an emotional vantage point. How does anxiety manifest itself in action and interiority? How about loneliness and longing? How about rage?

The more helpful answer is that I’ve spent years writing and reading flash fiction where the economy of words creates a negative space around a story. What is left off the page is as important as what is included. Knowing your characters and letting them sink into their own feelings, I think, allows you to go deeper faster, and—I hope, if I’m doing my job correctly—then the silences will capture that feeling of emptiness but won’t be empty themselves.

10. Outside of your own writing, you are the fiction editor at Barrelhouse. What are some things you’re paying particular attention to right now, when looking for writers and works of fiction to amplify? What types of stories do you wish were being published more in today’s literary landscape?

I’ll be honest, I have such a small window into the literary landscape as a whole. There’s so much work out there that it’s hard for me, personally, to keep up, though maybe that’s not a bad thing. But in general, I’m always looking to laugh, and I’m always looking for stories that feel current, that are grappling with questions about what it means to be alive. That’s very broad, I guess.

I’m always drawn to writing by other queer authors of color, whether they’re writing about joy or anger or quiet narratives or love or sex or food or popular culture or anything, really. More of all of that.

Christopher Gonzalez is a queer Puerto Rican writer and the author of I’m Not Hungry But I Could Eat, published by Santa Fe Writers Project in December 2021. He is a recipient of the 2021 Artist Fellowship in Fiction from the New York Foundation for the Arts, and his writing has appeared in The Nation, Catapult, Best Microfiction, and Best Small Fictions, among other journals. He currently serves as a fiction editor at Barrelhouse and lives in Brooklyn, NY but mostly on Twitter at @livesinpages.