The PEN Ten: An Interview with Mina Seçkin

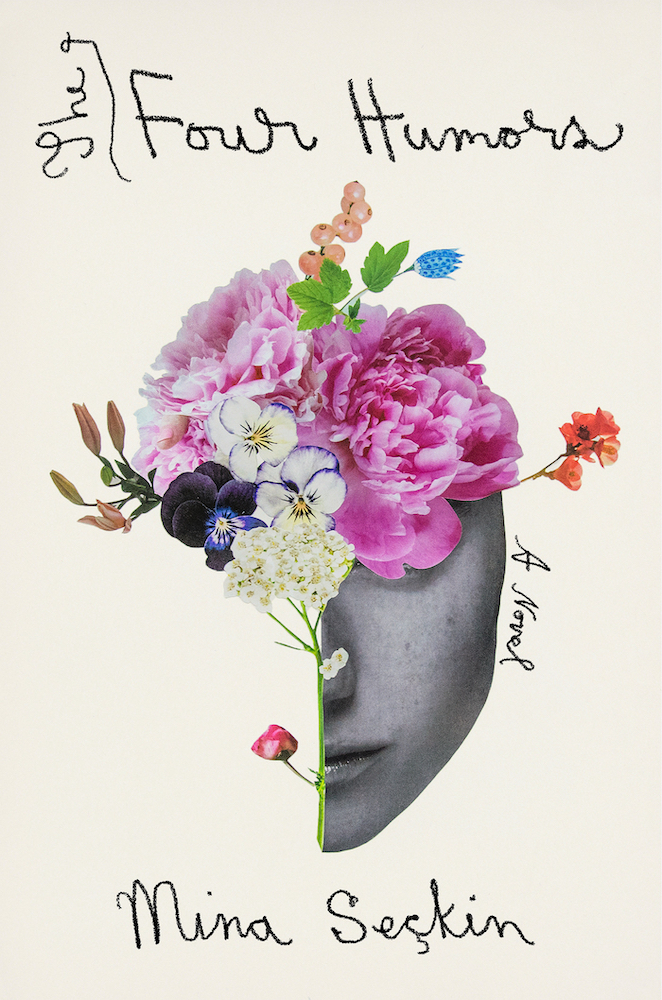

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Nancy Vitale speaks with Mina Seçkin, author of The Four Humors (Catapult, 2021) – Amazon, Bookshop.

Photo by Max Voreacos

1. Given the nature of your fantastic book and the perceptions of health and wellness that you explore, how the hell are you feeling at this point in the pandemic, where so many of us are questioning what is healthy?

It has been eerie—so much of The Four Humors is about questioning what’s healthy, and the lengths people will go to find psychological and physical equilibrium. It’s also about taking care of others. Have we taken care of each other during this ongoing pandemic? In a macro sense, no, I don’t think so. But on a smaller scale, and within local communities, families, and friends, I’ve seen more care and have felt more hope.

I’ve also been thinking a lot about the system of power that has been embedded in medicine since ancient times. Physicians practiced the four humors theory of ancient medicine—where the blood, black bile, phlegm, and choler in your body was thought to determine your physical and psychological wellbeing—for 2,000 years. Even after French chemist and microbiologist Louis Pasteur discovered germs in the 19th century, doctors were still performing bloodletting as the primary cure for ailments (despite the rumors that Mozart and George Washington may have actually died from bloodletting procedures meant to treat them).

Medicine is a constantly evolving field: one where there are still many unknowns, misdiagnoses, and missteps. The individual labor that physicians, scientists, and researchers perform is also subject to a larger system of control—and it can take decades (or in the four humors’ case, centuries) for groundbreaking research to become the norm. The pandemic has floored me by the reality that the human body is vulnerable not just to viruses and disease, but also to the social and political systems set in place to determine who gets treated, how, when, and at what exorbitant cost.

“Any language is meant to evolve, and it must do so in order to keep approximating feeling and experience as closely as possible. Living in two languages—neither spoken with exact accuracy—built a house of expression for me growing up. I learned the ways bilingual and broken English could break and rewrite the rules of what is allowed to be said—and more importantly by whom.”

2. What is your favorite bookstore or library? I noticed that, like me, you’re a Columbia MFA grad. I was down at Hungarian Pastry Shop reading your book last week, and I saw two people pointing to the cover knowingly. Given the propensity for so many Columbia MFA students to live/work at Hungarian Pastry Shop, it made me wonder if the better question is, “Where do you like to write?” (Obviously, Hungarian doesn’t need to be the answer.)

Wow, I love Hungarian Pastry Shop—I did write there quite a lot during my college and MFA years. Their croissants are my favorite in New York City—doughy, not flakey, and very buttery and plush—but I have gotten involved in one too many disputes about this topic. Some people don’t think Hungarian’s croissants are even croissants! Appalling.

My writing habits are very fluid though, and dependent on the locational phase of my life that I’m in. For years, I was a library and café rat,ędue to school, and that feeling where I have everything in my bag for the day and can’t go home until I’m done with a project. Then, especially with a day job, I became a slovenly person who came home from work and wrote best from bed. I regret to say writing from bed doesn’t work for me anymore. Lately, I’ve settled into a large wooden desk that used to be my dad’s, and I’m finding it incredibly fruitful to focus.

But I still don’t have a fixed writing practice. I try my best to write what means something to me without creating goal posts to assess how productive I’ve been, how “good” or worthwhile. I think those practices limit creativity. Still, you must get a story out of you when you want to, and I do believe you must sit down and lock in to do so. When I lock in, it’s all-consuming, and where I am or whether I’m eating a croissant doesn’t matter at all.

3. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi. I was nine years old and devastated by it. Turkey and Iran’s histories are very different, but as a child, I remember becoming hyperaware of my parents’ former lives and how they spoke about their motherland: Turkey. Why did they come to America? Did something similar happen to them? I read Persepolis a few weeks before 9/11. A lot of growing up occurred in that time period, where I was forced to reckon with my family’s otherness in America. I am really grateful for that book.

“An idea I always draw from [Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy] is similar to faces in dreams: Apparently, every face you see in a dream is one you’ve seen before in your waking life. Writing and reading about place feels similar to me. There’s a place you know that you’re writing toward, whether it’s your grandmother’s kitchen or your parents’ kitchen (two unescapable hearths in my own writing). Nonetheless, when a reader absorbs your description, they infuse your details onto their own blueprint.”

4. What is the most daring thing you’ve put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I am a bit terrified that I’ve written a novel about Turkey. Elif Batuman, an idol of mine, writes on her website, “It is no joke writing a book about Turkey.” I always think about this line—which, yes, is on her website and I’m here quoting it as if from a textbook or bible. Some people may not like what I’ve written in The Four Humors in relation to sexuality and gender, but that’s why I had to write it. I would not take any of it back.

5. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

Etel Adnan’s poetry, prose, and visual art. Her work has been the most stupendous and moving representation of the Middle East to me—its pain, body, and joy.

6. What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

My parents are both immigrants, and their English isn’t “perfect”—a word that I’ve been obsessed with from a young age as it relates to language. My dad in particular mispronounces words and composes sentences in grammatically incorrect English. But in his supposed missteps, he reaches for words with poetry and rhythm instead. He produces beautiful sentences that are free of clichés. This is my read, and it’s come from many years of people correcting his English—even my English—and experiencing othering through a policing of language.

But any language is meant to evolve, and it must do so in order to keep approximating feeling and experience as closely as possible. Living in two languages—neither spoken with exact accuracy—built a house of expression for me growing up. I learned the ways bilingual and broken English could break and rewrite the rules of what is allowed to be said—and more importantly by whom.

“Birding is about attention and observation—I find it’s a very relaxed and gentle way to observe the world around you. If writers ever had a singular personality trait, I do think it would be being extremely observant. It’s also fleeting—the bird is there, your heart fills with joy, and then the bird is gone. What a short yet powerful joy!”

7. What is your relationship to place and story? Are there specific places you keep going back to in your writing?

There’s this incredible illustrated book called What We See When We Read by Peter Mendelsund. I recommend it for anyone who is a writer or an artist or a reader. Mendelsund is a cover designer—he’s designed the covers for the new James Joyce and Dostoyevsky editions—and he writes about the phenomenology of reading. Although it’s not intended to be a book about craft, it’s the best craft book I’ve ever read. When you’re reading Anna Karenina, for example, and visualizing Anna Karenina, Tolstoy gives only a few details about her face—her nose shape, her eyes—in order to form a picture in your mind. And those scant details are all you need. The picture that you form is yours, and not necessarily what Tolstoy intended.

An idea I always draw from this book is similar to faces in dreams: Apparently, every face you see in a dream is one you’ve seen before in your waking life. Writing and reading about place feels similar to me. There’s a place you know that you’re writing toward, whether it’s your grandmother’s kitchen or your parents’ kitchen (two unescapable hearths in my own writing). Nonetheless, when a reader absorbs your description, they infuse your details onto their own blueprint.

While place is central to story, I never address it head on in my writing. It’s always character-first for me, which then demands scene, which finally demands place. I admire writing that feels place-forward, but I can rarely write more than three consecutive sentences describing a place. I get bored!

8. Your novel speaks so deeply of familial connections and inherited trauma. If you could claim any writers or books from the past as part of your own literary genealogy, who would your ancestors be?

8. Your novel speaks so deeply of familial connections and inherited trauma. If you could claim any writers or books from the past as part of your own literary genealogy, who would your ancestors be?

Leyla Erbil’s A Strange Woman and everything Miriam Toews has ever written. Both depict young women who want to carve out a life for themselves among inherited family trauma. Both are also as funny and dry as they are heartbreaking. A Strange Woman (Tuhaf Bir Kadin) is the story of a family in Istanbul told in four parts. My favorite is the first section, about a young female poet, Nermin, during the 1950s. The intellectual and anarchist world Nermin wants to enter is primarily made up of men—men who don’t think she can write. When she’s finally invited to a coffeehouse to read her poetry, she reads a poem about menstruation. The dudes don’t get it, and she’s furious. She’s falling in and out of love with various unfit suitors while also battling her parents, who don’t approve of Nermin’s politics and turn toward secularism. It’s a big-hearted and boundary-breaking novel. I’m really excited that Deep Vellum is publishing the English translation in 2022 (translated by Nermin Menemencioğlu).

Miriam Toews isone of my favorite novelists. I fall in love with every single one of her narrators. Each moves through the world with an absurdist, earnest humor that wins me over each time. Like in A Strange Woman, inherited family trauma is inescapable in Toews’ work, and family is always explored with utmost tenderness.

9. I noticed, too, from your Instagram that you are an admirer of birds of all shapes and sizes. How does this interest manifest in your work?

I am indeed a huge admirer of birds! Birding is about attention and observation—I find it’s a very relaxed and gentle way to observe the world around you. If writers ever had a singular personality trait, I do think it would be being extremely observant. It’s also fleeting—the bird is there, your heart fills with joy, and then the bird is gone. What a short yet powerful joy! I think so much writing and art-making is about trying to pin a short yet powerful feeling onto the page. A feeling you can’t recover in any other way.

10. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

I just read Hard Damage by Aria Aber. I also read Call Me Zebra by Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi for the first time. I was blown away by both. I’m reading and really enjoying Win Me Something by Kyle Lucia Wu now, and I’m so excited to read White on White by Aysegul Savas, which comes out in December.

Mina Seçkin is a writer from Brooklyn. Her work has been published in McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, The Rumpus, and elsewhere. She serves as managing editor of Apogee Journal, and The Four Humors (Catapult) is her first novel.