The PEN Pod: Connecting through Translation with Ali Araghi

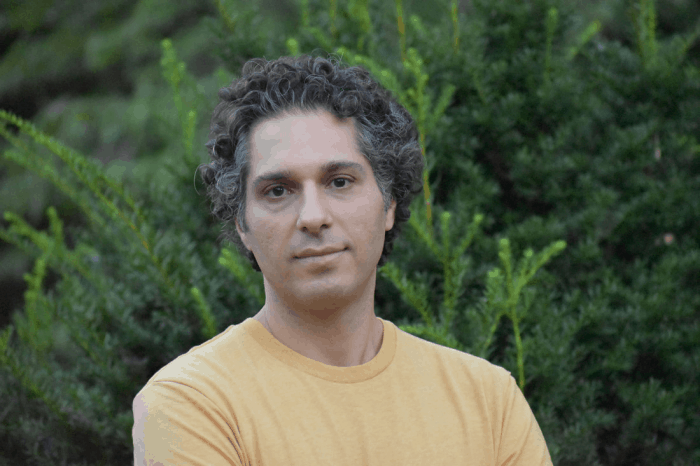

Photo by Vahid Khalajzadeh

Today on The PEN Pod, we spoke Iranian writer and translator Ali Araghi. He is the author of the novel The Immortals of Tehran and the founding editor of the online literary journal PARAGRAPHITI. Currently, Ali is a PhD student in comparative literature at Washington University in St. Louis, and alongside his second novel, he’s also working on Persian, Translated, a database of Persian literature translated into English. We spoke with Ali about how he’s dealing with the uncertainty of this moment, the process of writing The Immortals of Tehran, and the comforts that translation can provide, especially during a time when the world feels especially closed off.

How are your family, friends, and colleagues in Iran? What do you hear about what’s happening there?

My family has been okay so far. And by “okay,” I mean they have managed not to get infected so far. My mother had knee replacement surgery on both her knees about six months ago, so she had to stay home to recover. So in that sense, she had been practicing some kind of quarantining for some time. But on the other hand, she had to start taking walks after a few weeks to help the prosthetic joints work. But now she has to either skip those walks or shorten them. Most people I know are trying to stay home. Actually, the past two weeks were the New Year holidays in Iran. Iranian New Year starts with the first day of spring, and it’s a rather social type of holiday. People usually visit their families and friends, and usually they begin with the older members of the family—grandfathers, grandmothers, uncles, aunts. There’s this age hierarchy. So, we can see that there is this recipe to get the most vulnerable members of the family infected. People have been trying to cancel those visits, trying not to take trips. A friend of mine has MS, and both his parents are on the older side, and they have a positive case in their building, so they have been staying at home.

“We all are now in the same boat, more or less. We don’t see what’s going to happen. There’s this feeling that all of us are in this together. We don’t know if we’re going to have our jobs in the next week or so, if schools are going to open.”

You had a piece in The New Yorker in which you tell the story about how you first came to the U.S. to study at Notre Dame, in Indiana, and that you were struck by people talking casually about their future plans and by how they had a certainty about the future. What do you mean by that? And now that we’re all facing a certain degree of uncertainty, I wonder if your perspective has changed at all in that piece?

I was trying to make the point that my future back in Iran was less foreseeable than when I came here. And I was trying to think of that in terms of man-made sociopolitical structures that created those futures differently, in two countries. I was trying to be very personal in that article and not to generalize my experience as a kind of “typical Iranian experience” versus an American one. Of course, these societies are not monolithic. Those experiences were not universal. I have no doubt that many people here in the U.S. had much less predictable futures than me, and there were a lot of people in Iran who had much more certainty about their futures. The key word there was “man-made.” But, things have changed here. The outbreak in the past couple of weeks has had a kind of democratic—that’s too positive of a word, maybe—a kind of universal or global effect around the world, including here in the U.S. I feel like it’s the same effect, that we all are now in the same boat, more or less. We don’t see what’s going to happen. There’s this feeling that all of us are in this together. We don’t know if we’re going to have our jobs in the next week or so, if schools are going to open. So in that sense, there seems to be a very unfortunate similarity between the two experiences.

I want to talk about your book, The Immortals of Tehran, which is a family saga. Obviously it’s a work of fiction, but how much did you draw on your own family history, family stories, family fables to piece this together?

I want to say little. If someone looks deep into my life and psyche, they would find certain aspects of me, of my life, in the novel. I’m going to give you some examples, perhaps the most obvious ones to me, at least—the protagonist, Ahmad, his great-great-great-great grandfather is a very old man. No one knows how old he is. His name is Agha, which is what I called my grandfather. Perhaps one of the reasons that the working title of the novel was “Agha,” was because my grandfather was very dear to me. But other than that, there’s not much similarity between that character and my grandfather. My grandfather didn’t live particularly long enough. My mother got divorced when I was very little and remarried. I grew up living with my stepfather. So maybe the absence of the father in the novel and this strong mother character would be a direct link to my own life. And the other thing is that I myself started off as a poet before I quit writing poetry and turned to fiction. But other than that, like I said, there’s not a lot that I can think of that ties directly to my own life. And honestly, even those connections don’t feel very, very personal to me. I’m certainly not directly borrowing from my own life. Maybe unconsciously, perhaps.

“One function of translation we could think about is the way it shows how literature of other cultures have reacted to similar problems we are dealing with.”

You’ve also worked as a translator. What do you think about the power translators play and in bridging divides, especially right now when the world feels so closed off?

Honestly, literature, without translation, doesn’t mean much to me. Even “normal times,” when there is no pandemic, the concept of “national literature” feels a little bit myopic and claustrophobic to me. My reading lists have always been very eclectic. From a very young age, I read books in translation, as well as those written originally in Persian. And it was not just me, it was not like my personal choice. The Iranian literary market in general is more open to translations. Some statistics I have from a few years back say that about 20 percent of all titles published in Iran in 2013 were in translation, and it doesn’t seem like the number has dropped in the past year. Now, if you compare that number with the famous three percent in the U.S., that tells you something about the status of translation in the two literary scenes. In that sense, not much has changed for me personally. Actually, all the books I’m reading now are in translation. But maybe one function of translation we could think about is the way it shows how literature of other cultures have reacted to similar problems we are dealing with. To give an example, our pandemic situation is not something that’s happening for the first time in the world. Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron is, famously, a collection of tales from 14th century Italy, ironically. There’s a number of people taking shelter in a villa to escape the Black Death, and they’re telling each other tales. I’m not suggesting that we should take medical advice from 14th century Italian manuscripts, but it’s good to know that there were other people in the world that had similar experiences. More recently, there was The Plague by Albert Camus and José Saramago’s Blindness that talk about afflictions that affect a big population. These are just a few examples of how other writers and other cultures have seen and felt situations similar to ours, and they come to us through translation.

Authors have often taken advantage of moments of global pandemic or panic to actually write some of their greatest works, even if they have nothing to do with disease. Are you finding that you are able to write right now?

I do find myself able to write in this situation. I am not writing at this moment, because I’m busy with schoolwork and a lot of events happening around the publication of the novel. But there’s one thing that hasn’t changed that drastically about my life, and it’s the fact that since I moved here to the U.S., I don’t have that large of a network of friends and family, so it kind of feels like in the past couple of years, I have lived a kind of hermit-like life that a lot of us are experiencing right now. Of course, it’s much more restricted and limited right now, but the change has not been as drastic for me as for a lot of other people around me.

Send a message to The PEN Pod

We’d like to know what books you’re reading and how you’re staying connected in the literary community. Click here to leave a voicemail for us. Your message could end up on a future episode of this podcast!