Rachel Eliza Griffiths | The PEN Ten Interview

August 11, 2023

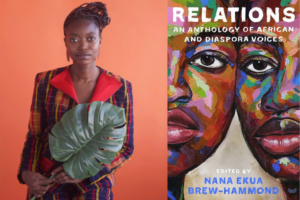

With the recent publication of her debut novel, poet and visual artist Rachel Eliza Griffiths adds novelist to her list of artistic achievements. In Promise (Random House, 2023), two young Black sisters come of age in a small New England town as the Civil Rights Movement builds momentum in the American South. Both together and separately, the sisters traverse family obligations, friendships, and budding levels of consciousness while navigating the everyday racism of their environment. As much as the novel is about resistance, it also digs deep to locate how to move forward in remembrance of the past.

In this PEN Ten interview with Malcolm Tariq, Senior Editorial Manager for PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, Griffiths gives insight into her writing practice and the intentionality behind language and history in the novel. (Amazon, Bookshop)

1. Most of your written work is in poetry. What inspired you to write fiction—a novel, no less—and what were the major differences in writing in this new genre? Has this changed your writing practice in any way?

I’ve always written both poetry and fiction simultaneously. Writing fiction isn’t new for me but having an audience for it is new. In terms of major differences between the two genres in this context, it’s about timing. When I was younger, my poetry was published sooner is all. I’ve got early short stories out there somewhere in some very tall grass from my twenties and I hope no one ever finds them. My writing practice is about writing and this means any and everything. Fiction and poetry don’t occur on any linear or binary spectrum for me. Experimentation, risk, embodiment, and curiosity form the spine of my practice. And so much more. These notions don’t exclude rigorous discipline, craft, or the awareness that genre is more often than not an external construct that helps us to see the boundaries and edges of our forms.

2. Most of the perspective of this book is from that of the protagonist, a young Black girl. What inspired you to write from the perspective of a young person?

I didn’t have a choice. Years ago, I heard her voice, which is partly mine, and her questions about how, as a Black girl or woman, to live in this world. And I don’t mean in order to survive, to provide free labor, or to provide identities for other peoples’ stories. This book was my attempt to assure young Black girls that there are beautiful, resonant ways to live, to investigate love, and to celebrate themselves. I wish I’d been told, and shown, more about beauty, joy, and vulnerability, and how to recognize it in myself when I was younger. Because there isn’t any single answer or power, any America, that keeps any of us safe.

“This book was my attempt to assure young Black girls that there are beautiful, resonant ways to live, to investigate love, and to celebrate themselves.”

3. Are there any similarities between the life of the young women in the book and your personal life? If so, why did you choose to incorporate those elements into the story?

There are parts of me in all of the women and men in the book, including the white women. And what I mean by that is memory. For example, I can remember being treated a certain kind of way, a wrong kind of way, by white women when I was a Black child and had no defenses. I would like to think that the spaces where my personal life merge with elements of Promise is mostly subconscious. I think it’d feel weird to be too aware of it. My writerly mind doesn’t find my personal life nearly as compelling as fiction.

4.There are a host of characters in Promise, but the Black women and girls in the book take center stage. Was this your intention when you set out to write the book?

Promise, like most of my literary and visual work, is a love letter for/to Black women and girls. I set out to write a novel for myself and for my late mother. I knew I would be approaching this narrative organically, with intuition and nuance. Powerful, defiant, incandescent Black women raised me and continue to encourage me to be free in my art and elsewhere.

“Powerful, defiant, incandescent Black women raised me and continue to encourage me to be free in my art and elsewhere.”

5. Reading this novel, I often thought of Ann Petry, who wrote about Black life in New England. Why was it important for this story about Black life, love, and resistance to be set in a small, New England village? What is your relationship to place, and this place in particular?

Promise is set in New England because it provided me with more space as a writer to engage my characters and their stories. When I was young and often visited New England, which is very beautiful but also isolating and raw, I asked myself what my life would be like if this was the landscape and atmosphere that raised me? In terms of geography, I was raised in the mid-Atlantic. But I also wanted to consider that the arrival of Black people to the North didn’t signify a pure freedom (there is none), or mecca, or that Black people were suddenly liberated from racial hostility and violence in America. For enslaved people fleeing terror in the South, the north is often portrayed as innocent and morally sophisticated. It felt important to push back against this gross illusion.

6. What were some of the challenges you faced writing this book and how did you overcome them?

This feels like a question for my therapist! All I can say is that life does not stay static because you are trying to write a book. A challenge I continue to struggle with is grief. While I try to find ways to live with grief and trauma, I don’t pretend it is something that I can overcome. “Overcoming” is overrated. Unless, perhaps, we are talking about illness or war.

7. Did writing this book change you in any way? Are there things that surprised you about yourself or your characters while writing this story?

Language startles me each day. I’ve experienced a hard tide of awakenings in my life, both vulnerable and powerful, that reach all parts of me. Writing without revelation feels senseless. For me, revelations exist at every level and vibration between wondrous gradations of extraordinary and ordinary. The characters in Promise feel miraculous to me because of their dimensionality. They feel marvelous because of how deeply I miss their daily company even when their desires and fears felt untranslatable. I was startled by how they made me become the kind of writer I’d never imagined. I feel fortunate for this knowledge. It can’t be stolen away. It will affect and transform whatever I might make going forward. We are living in a world that is unrelenting in speed, transmitting an uncanny and over-stimulating burden of information and sensation. The world of Promise forced me to slow down my expectations of my own capacity to match the frenzy of the world. All of the instruments available to me––my very life and the lives of others, known and unknown, to which I am connected––offer my imagination, my practice, and even my body, a profound and intimate cosmology.

8. As artists, we sometimes have other artists or artworks that serve as guides, inspiration, or safe havens for us while we’re producing major works. What artworks (literary or not) grounded you while writing this novel?

Promise took roughly seven years to complete. Art is a daily haven for me where I spend time feeling and experiencing it because art shifts what we discover is possible. Here are some artists that I stay close to for courage: Romare Bearden, Dawoud Bey, Sanford Biggers, Louise Bourgeois, Noah Davis, Gabriela Iturbide, Kerry James Marshall, Joan Mitchell, Gordon Parks, Howardina Pindell, Robert Pruitt, Faith Ringgold, Ming Smith, Betye Saar, Jack Whitten, The Kamoinge Workshop.

“I hope that readers will leave Promise with a sense of curiosity and a heightened awareness of what is at stake for each of us living in the personal and historical narratives and memories we have chosen and continue to create.”

9. What do you want readers to walk away with after engaging with Promise?

One of the things I love most about reading is coming away from a story with questions of my own about characters, their relationships to one another, and their relationships within the larger world. I’d like readers to sense that something powerful was at stake for me and for them. I want them to remember this intimacy that language and life demand and dream for us. I hope that readers will leave Promise with a sense of curiosity and a heightened awareness of what is at stake for each of us living in the personal and historical narratives and memories we have chosen and continue to create.

10. What’s the best piece of advice you’ve received about writing and publishing?

Many years ago, a song by Abby Lincoln found me called “Throw It Away.”

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is a poet, visual artist, and novelist. She is a recipient of the Hurston/Wright Foundation Legacy Award and the Paterson Poetry Prize and was a finalist for a NAACP Image Award. Griffiths is also a recipient of fellowships from many organizations, including Cave Canem Foundation, Kimbilio, the Provincetown Fine Arts Work Center, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, and Yaddo. Her work has been published in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Tin House, and other publications. Promise is her first novel.

The PEN Ten Interview Series

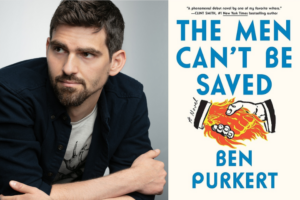

Ben Purkert | The PEN Ten Interview

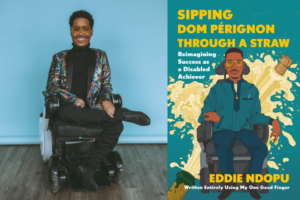

Eddie Ndopu | The PEN Ten Interview