Eddie Ndopu | The PEN Ten Interview

In an interview with Jared Jackson, Program Director for Literary Programs and Emerging Voices, Eddie Ndopu discusses the relationship between truth and heartbreak, the complexity and multiplicity of disabled people’s lives, and the need to create one’s own reality.

In an interview with Jared Jackson, Program Director for Literary Programs and Emerging Voices, Eddie Ndopu discusses the relationship between truth and heartbreak, the complexity and multiplicity of disabled people’s lives, and the need to create one’s own reality.

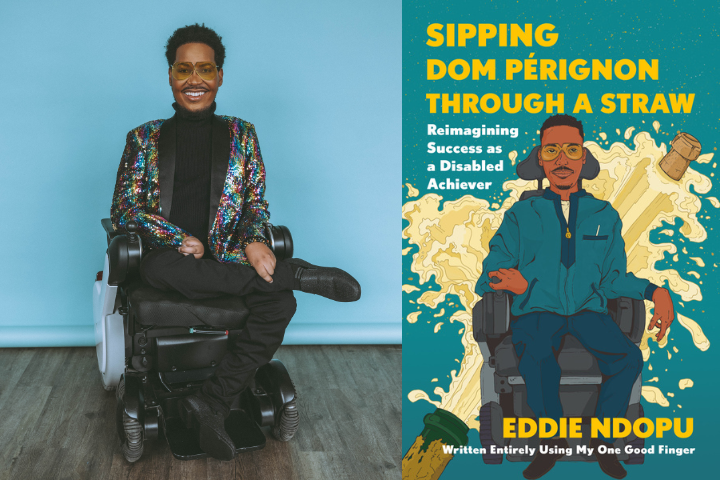

For years Ndopu has been one of the preeminent voices on disability justice advocacy. Now, he brings his much sought after oratory wisdom to the page in an insightful and humorous memoir Sipping Dom Pérignon Through a Straw. A generous offering, Ndopu, through self-reflection, provides a blueprint to living a full life.

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

Woman at Point Zero by Nawal El Saadawi.

2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction?

Truth and heartbreak go together in my writing because the truth is often heartbreaking. The truth that my success has not been able to inoculate me against the quotidian reality of ableism is a heartbreak that I spend the entire narrative trying to grapple with and work through. Memoir, when done right, functions like a sort of concentrate for truth. Not so much the truth of events as they are remembered but the truth of the human condition as it is retold on the page.

“Memoir, when done right, functions like a sort of concentrate for truth. Not so much the truth of events as they are remembered but the truth of the human condition as it is retold on the page.”

3. In the description of your memoir, Sipping Pérignon Through a Straw, it notes that it was “penned with one good finger.” Can you share more about what the creative process looked like? As a sought-out speaker, what made you want to write a book? How did you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

My creative process involved my iPhone, on which my entire book was written, and tons of Red Bull. It’s not the sexiest or healthiest mode of writing, but it’s what enabled me to get the task done. I wrote this book because I needed to tell the truth of my experiences navigating institutional life as a disabled person.

4. Along with educational advocacy, you’ve been a disability justice advocate since your late teens. How do the two intersect, if at all, and what has been your experience speaking on them?

Disability justice is the broader discourse under which my advocacy for inclusive education has taken root. Disability justice looks at everything. It focuses on the entire ecosystem of what constitutes a just and dignified life for disabled people. But it also says that if disabled people get free then everyone gets free.

“One of the worst ways in which we dehumanize people is by denying them complexity and multiplicity. Disabled people tend to encounter this often, almost on a daily basis, where our lives get boiled down to logistics.”

5. What is the last book you read? What are you reading next?

Last book was South to America by Imani Perry and my next book is The Covenant of Water by Dr. Abraham Verghese.

6. What do you consider to be the biggest threat to free expression today? Have there been times when your right to free expression has been challenged?

The biggest threat to free expression today is actually the ways in which the term and concept is being redefined and misunderstood on purpose in order to serve an agenda that is actively trying to restrict freedom for marginalized groups in particular. It’s really disturbing to me how a word like “woke” for example has been bastardized by extreme elements on the right to effectively deny entire swathes of people from being able to live freely. That’s the entire purpose of discrimination and exclusion, to limit free expression.

7. The memoir examines the pain of alienation, the nuance of romantic interest, and the humor of life. How did you set out to balance its various themes? Is there a specific idea you want readers to take with them?

One of the worst ways in which we dehumanize people is by denying them complexity and multiplicity. Disabled people tend to encounter this often, almost on a daily basis, where our lives get boiled down to logistics. I wanted to explicitly show how violent bureaucracy can be. My entire book is essentially an indictment of “reasonable accommodation” – its logic, its premise, its real-world application. There’s a line in the book where I say “in the same way that there’s nothing reasonable about expecting a whale to feel accommodated in an Olympic-sized swimming pool, there’s nothing reasonable about expecting a disabled person to feel accommodated in an ableist world.” We need the whole damn ocean to survive. For me, the whole damn ocean is where we grapple with the pain of alienation, the nuance of romantic interest, and the humor of life. It’s where everything is felt and experienced.

8. How does your identity shape your writing? Is there such a thing as “the writer’s identity?”

I definitely think that there’s an identity to my writing. It’s simultaneously cheeky and incisive, which at first blush sounds contradictory or paradoxical, much like sipping fine champagne through a straw. The tension between pathos and levity in my writing is really the literary manifestation of the tension I feel everyday living in a world that is not set up to meet my needs and yet still insisting on carving out a space of beauty.

“Appeasement will never protect us in the way we think it will. We need to save ourselves. We need to show ourselves the kind of tenderness and compassion that we know deep down we deserve.”

9. What is the most daring thing you’ve ever put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

The most daring thing I’ve ever written, that I could ever write, is this: I need, I want, I deserve… essentially, it’s all the times when I have had to articulate myself without apologizing or fawning. That’s radical because we live in a world where we as disabled people especially have to minimize ourselves in the name of survival.

10. In the memoir you share that there’s a certain point in a disabled person’s life that they’re told to start living realistically, meaning not being able to do things that nondisabled people can do with their bodies. What advice do you have for those who feel, as you write and have felt at one point in your life, “bogged down by the weight of ableism?”

To recognize that the true source of our suffering is when we acquiesce to the shrinking of ourselves out of a need to survive. Appeasement will never protect us in the way we think it will. We need to save ourselves. We need to show ourselves the kind of tenderness and compassion that we know deep down we deserve. Rather than living realistically, we need to create our realities.

Described by TIME magazine as “one of the most powerful disabled people on the planet,” Eddie Ndopu is an award-winning global humanitarian and social justice advocate. He serves as one of the UN Secretary-General’s SDG Advocates and sits on the board of the United Nations Foundation. Ndopu has been featured in Forbes, Global Citizen, Rolling Stone, Guardian, OkayAfrica, and more. He lives in New York City.