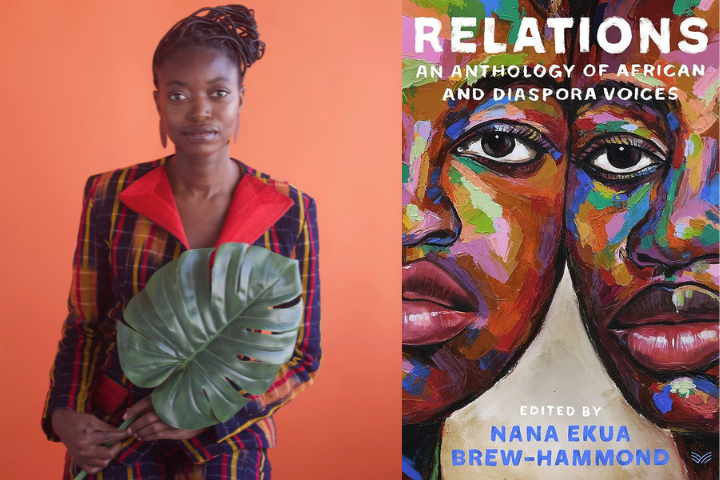

Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond | The PEN Ten Interview

In conversation with World Voices Festival Associate Director, Sabir Sultan for this week’s PEN Ten, Nana speaks about the process of creating the anthology, her body of work, and the writers and books she’s excited about today. (Amazon, Bookshop).

Relations: An Anthology of African and Diaspora Voices, edited by Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond, is a polyphonic collection of stories, essays, and poems from African writers and writers of the greater African diaspora. Written in different languages and various vantage points of faith, class, and identity, the collected works highlight the diversity of black voices and ground them in a shared set of relations.

1. Relations: An Anthology of African and Diaspora Voices brings together over 30 writers from Africa and the African diaspora and collects their stories, essays and poems. Why was this collection necessary now?

I think this collection is necessary because we all have relations in our lives. Most of us can identify with either the joy of a meaningful connection, or the feeling of betrayal related to a cheating partner, or the profound feeling of loss when a loved one passes on, or the pressures and expectations people close to us can place on us. For a very long time, those with the power to publish or produce stories in books, magazines, and films have presented these issues of life, which are common to all, almost solely in white skin. This anthology flips the POV and invites readers to experience various permutations of life through people of African descent. As the world is currently paying more attention to music, fashion, literature, and more coming from the continent—even as racist violence joins initiatives to suppress Black people around the world—Relations offers a place for us to learn about each other and accept how fundamentally connected we all are.

2 You begin your introduction to the collection recalling a conversation with a man born and raised in Morocco who tells you, “I’ve never been to Africa.” Why did you open the collection with that story?

I introduced the anthology with my recollection of this initially flirtatious encounter because that moment seemed to perfectly encapsulate how revelatory and enduring relating with another human can be, even in fleeting interactions. At the same time, it showed that African identity is not only not monolithic, it’s incredibly complex: You have people born or living on the continent who don’t consider themselves African, while there are others who were not birthed or raised in the geographical location, but claim their Africanness. Relations explores this complexity through a diversity of encounters.

“As the world is currently paying more attention to music, fashion, literature, and more coming from the [African] continent—even as racist violence joins initiatives to suppress Black people around the world—Relations offers a place for us to learn about each other and accept how fundamentally connected we all are.”

3. You write “With this anthology, my goal was to create a meeting place for those of us connected by shared color or continent, but often separated by country, language, history, experience or outlook.” As you edited and selected pieces for the anthology, were there any communalities you found that surprised you?

One thing I noticed in many of the pieces was betrayal. Whether by an unfaithful partner, a religion or church, or a country, several contributors wrote of the acute sense of disconcertion that comes when hope is dashed or trust is destroyed. I don’t know that I was surprised by this, but as I think about and answer this question now, it makes me want to study more deeply how betrayal works to shift us, and what the ramifications are when a group is shifted by it.

4. Is there a piece in the anthology that changed how you thought about the anthology as a whole or what the anthology could do?

When I approached potential contributors to Relations, I told them they could write whatever they wanted, whether it had to do with their interpretation of relations/relationships or not. I was expecting intriguing and artfully crafted submissions, and that’s what I received, but I was excited to find that writers who are popular for their poetry turned in fiction. Likewise, authors of fiction turned in essays, and a few turned in poetic hybrid forms. Their courage in submitting styles and genres they aren’t known for, even as they wrote about deeply personal and complicated topics, pushed me to work even harder at making sure this anthology wasn’t only an academic or entertaining offering. This book had to engage readers’ minds as well as their hearts. I hope the writers who read it will feel inspired to experiment with and publicly present new forms.

“I was expecting intriguing and artfully crafted submissions, and that’s what I received, but I was excited to find that writers who are popular for their poetry turned in fiction. Likewise, authors of fiction turned in essays, and a few turned in poetic hybrid forms. Their courage in submitting styles and genres they aren’t known for, even as they wrote about deeply personal and complicated topics, pushed me to work even harder at making sure this anthology wasn’t only an academic or entertaining offering.”

5. You’ve written short stories, poems, a young adult novel, a children’s book and now edited and published an anthology. How do you see Relations fitting into your broader body of work?

Relations, like all of my work to date, is invested in expanding the mainstream POV to include the overlooked, ignored or unexpected. With my children’s book BLUE: A History of the Color As Deep as the Sea and as Wide as the Sky, I was interested in writing a history that presented more than one culture’s experience with the color. With the poem I recently wrote for the Brooklyn Museum’s Africa Fashion film, I wanted to show the breadth of African style by giving specific examples of techniques and traditions from different countries across the continent. With my young adult novel Powder Necklace, I wanted to share the “reverse immigration” experience. At the time I was writing it, I had read books about emigrating from Africa to Europe or America, but had not found many narratives about the experience of a first generation American or European from an African country returning to live on the continent. I am incredibly fortunate to have had the opportunity to publish in so many different formats, and I don’t take the privilege lightly at all. I want my work to always be the truest expression of where I am/was at the time I produce(d) it. I never want to be boxed in, even by my own vision or goals.

6. As a Ghanaian and American author based in the US, like many of the writers in this collection, some of your stories take place in a country you no longer live in. How do you see your work speaking to people living in Ghana? Are they part of the audience you envision when writing?

Perhaps because my Ghanaian identity was often called into question when I was in high school there, and still is when I visit, I am hypersensitive to not only how Ghanaians living in Ghana will receive my work, but how I can get my work into their hands so we can dialogue about it. Since my publishers don’t currently distribute in Ghana, when Powder Necklace came out in 2010, I partnered with a bookstore in Accra to carry the book and held a book release party to engage book lovers, educators, and librarians. Similarly, for BLUE, I did in-person and virtual events across Accra to connect with booksellers, schools, libraries, and more. I’m excited to do the same for Relations, and hope to have events with the fifteen contributors who are resident on the continent in their localities. Right now the anthology is available at Chez Alpha Books in Dakar and we have been discussing timing for an event with Ayesha Harruna Attah who contributed the lyrical short story “Nanyuman” to the collection.

7. What do you see as the biggest threat to free expression today?

I think the biggest threat to free expression today is rushed expression. We have more capacity than ever to take in wide swaths of information—and a simultaneous, though mostly artificial, pressure to process and respond right away. This confluence has us in a sound byte / hot take / clever rejoinder culture where it’s easier to disseminate the quickest quip over the lengthy, mulled over response. This puts a lot of pressure on us to join the chorus without taking time to sit with and form our thoughts.

8. What is the most daring thing you’ve put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I wrote a poem that offers a racy description of intimacy with God. It starts:

To the Author of sex:

You are my shuddering revelation

An insurmountable girth

Splitting my flesh into

A rainbow of pleasure and pain

An arc of blood and wine

A holy communion

On my skin, In my hair

I test positive with You…

I wrote it in response to a T.D. Jakes sermon I heard a few years ago that characterized some of the Psalms of David as David dating God. David writes in the 63rd Psalm, “I thirst for you, my whole being longs for you… on my bed I remember you, I think of you through the watches of the night. Because you are my help, I sing in the shadow of your wings. I cling to you; your right hand upholds me.” Rereading the Psalms with that provocative lens was incredibly intriguing and inspiring to me so I began working on a series of love poems to God.

“Relations, like all of my work to date, is invested in expanding the mainstream POV to include the overlooked, ignored or unexpected.”

9. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

I’ve been working on a novel and a few other projects so I have not read for pleasure in a while. As soon as I hit “send” to my editor, though, I’m most looking forward to tucking into Gothataone Moeng’s Call and Response, Magogodi ooMphela Makhene’s Innards, Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water, Vanessa Walters’ The Nigerwife, and yes, Prince Harry’s Spare.

10. Finally, it’s a huge milestone publishing your first novel. What’s next for you?

Buchi Emecheta’s The Joys of Motherhood, Tayari Jones’ An American Marriage, Zadie Smith’s White Teeth, Janet Fitch’s White Oleander, Sharon Draper’s Copper Sun, and Chinua Achebe’s A Man of the People are my literary north stars. Each is its own masterclass in pacing, irony, character, tragedy, humor, timeless relevance, and bravery. I aspire to produce a work that ably synthesizes all of these elements.

Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond is the author of the children’s picture book BLUE: A History of the Color as Deep as the Sea and as Wide as the Sky, illustrated by Caldecott Honor Artist Daniel Minter. Named among the best books of 2022 by NPR, New York Public Library, Chicago Public Library, Kirkus Reviews, The Center for the Study of Multicultural Literature, and Bank Street College of Education, BLUE was honored with the 2023 NCTE Orbis Pictus Award® recognizing excellence in the writing of non-fiction for children, included on the Texas Bluebonnet Award Master List, and nominated for an NAACP Image Award. Brew-Hammond also wrote the young adult novel Powder Necklace, which Publishers Weekly called “a winning debut”, and she edited RELATIONS: An Anthology of African and Diaspora Voices, of which Kirkus Reviews said in a STARRED review: “This smart, generous collection is a true gift.” Every month, Brew-Hammond co-leads a writing fellowship whose mission is to write light into darkness.