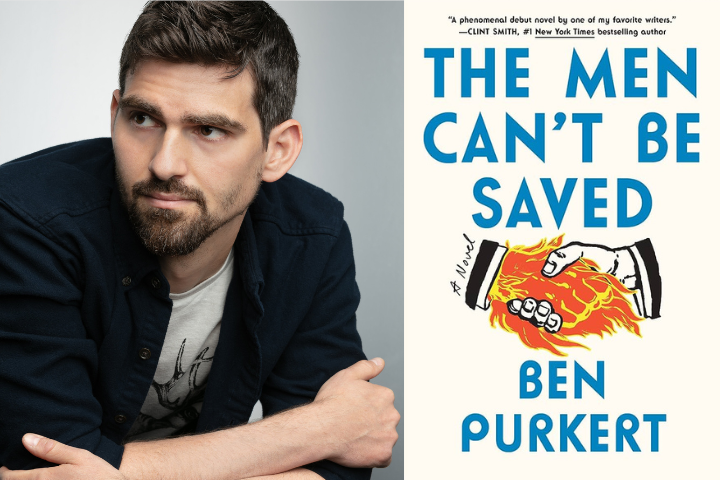

Ben Purkert | The PEN Ten Interview

Ben Purkert’s hilarious debut novel, The Men Can’t Be Saved, follows Seth Taranoff, a junior copywriter at an advertising firm after he loses his job and with it his sense of self. The novel follows Seth as he searches for meaning through faith, drugs, and desire in a skewering take on workplace culture and masculinity.

In conversation with World Voices Festival Associate Director, Sabir Sultan for this week’s PEN Ten, Ben speaks about his process writing the novel, Seth’s sense of self, and the responsibility of keeping a reader’s attention. (Amazon, Bookshop).

1. The Men Can’t Be Saved is your debut novel, but your second book. In 2018 you published your debut poetry collection For the Love of Endings. How was the experience of writing your novel similar to or different from writing your poetry collection?

The biggest difference, frankly, was that I had no idea what I was doing! I’ve studied poetry for a large portion of my life, but I’d never taken a single fiction class before. I felt completely in the dark. But the cohesive project of telling a single character’s story, that pulled me through. It grounded me. It also helped that, structurally, I kept things simple: I told one narrative from beginning to end.

2. After Seth loses his job at the advertising agency, we see him flounder and search for meaning through drugs, faith, and love interests, but all the while never letting go of the notion of himself as a brilliant copywriter, despite constant evidence to the contrary. Why is his sense of self so inextricably intertwined with his job?

I think that this intertwining of self and job is hardly unique to my main character. It’s a much more widespread phenomenon than that, and it’s particularly pervasive here in the U.S. where we so frequently identify ourselves–and value ourselves–according to our professional titles. It’s the first question we ask each other upon meeting: What do you do? In other countries and other cultures, an introduction might round out into a different form, but here it’s almost always how we begin.

“I think that this intertwining of self and job is hardly unique to my main character. It’s a much more widespread phenomenon than that, and it’s particularly pervasive here in the U.S. where we so frequently identify ourselves–and value ourselves–according to our professional titles.”

3. Nearly all of the male characters in the novel Seth, Rabbi Jacobwitz, and Moon, an executive from Seth’s former advertising firm, are failing the people in their lives in various ways. The novel’s title, The Men Can’t Be Saved, and Seth’s journey all highlight the dangers of stereotypical or toxic masculinity. What did you want to explore about modern day masculinity in the novel?

My main character says he desperately wants to make partner at his agency, but I personally don’t believe that that’s what he really wants. I think he longs for partnership in a different sense. Closeness, intimacy, brotherhood. These are the things that he actually craves. But he isn’t able to articulate that desire, or find access to a broader emotional vocabulary that would allow him to express it. This is related, it seems to me, to certain questions around how particular forms of masculinity are constructed.

4. From a Birthright trip to Israel to being taken in by an Orthodox rabbi, the reader sees Seth attempt to make sense of being Jewish and to understand faith broadly. What is Seth’s relationship with Judaism?

When Seth gets laid off, he struggles mightily with his sense of self. For so long, he’s defined himself based on his agency copywriting position–now that it’s all taken away, who will he be? It’s then when his Jewish identity really comes into play. Being Jewish is something that he can never lose. It goes much deeper than that.

“My main character says he desperately wants to make partner at his agency, but I personally don’t believe that that’s what he really wants. I think he longs for partnership in a different sense. Closeness, intimacy, brotherhood.”

5. Without giving too much away, one of my favorite comic sequences in the novel follows Seth enlisting the rabbi’s young son with cystic fibrosis, in stalking Seth’s ex. Reading the section I alternated between laughing and turning away in secondhand embarrassment. What was it like plotting out those events and Seth’s increasingly unhinged behavior? Did you worry at any point the novel was turning too dark?

Your question presumes that I plotted out the events in advance! In truth, I stumbled right alongside my main character; I followed Seth on his downward spiral and simply tried to keep up with my pen. And no, I didn’t worry that my novel was too dark. I only worried that it not be boring. I felt a huge responsibility to earn the reader’s sustained attention. A novel is a big ask.

6. Throughout the novel, from his former boss Diego, to Moon whose car he steals, Seth suspects other straight men of desiring him. Is this part of Seth’s egocentrism?

Sure. Though I also think it might provide a window into his desires too.

7. What do you see as the biggest threat to free expression today?

The shameful failure of governmental officials to allocate sufficient resources for public education at all levels.

8. What is the most daring thing you’ve put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I cycled through many titles before I landed on The Men Can’t Be Saved. It made me shudder a bit. I liked that about it.

“I followed Seth on his downward spiral and simply tried to keep up with my pen. And no, I didn’t worry that my novel was too dark. I only worried that it not be boring.”

9. What advice do you have for young writers?

Read as widely as you can and, as Tracy K Smith once said, read against your tastes. Don’t hem yourself in too early. Exposure is everything.

10. Which writers working today are you most excited by?

The ones whose names I haven’t heard of yet. The students. The young readers. The unpublished and underrepresented.

Ben Purkert is the author of the poetry collection For the Love of Endings. His work appears in The New Yorker, the Nation, and the Kenyon Review, among others. He is the founder of Back Draft, a Guernica interview series focused on revision and the creative process. He holds degrees from Harvard and New York University, and he currently teaches at Rutgers. The Men Can’t Be Saved is his first novel.