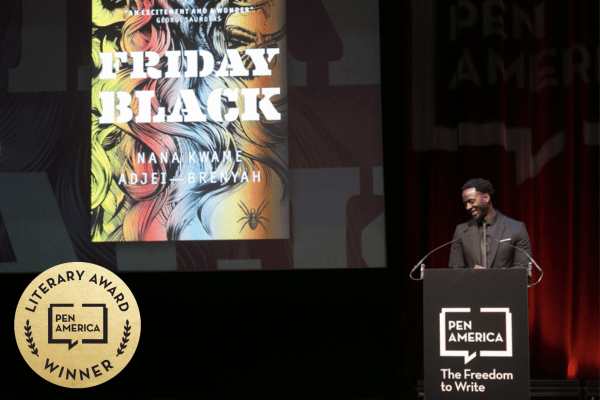

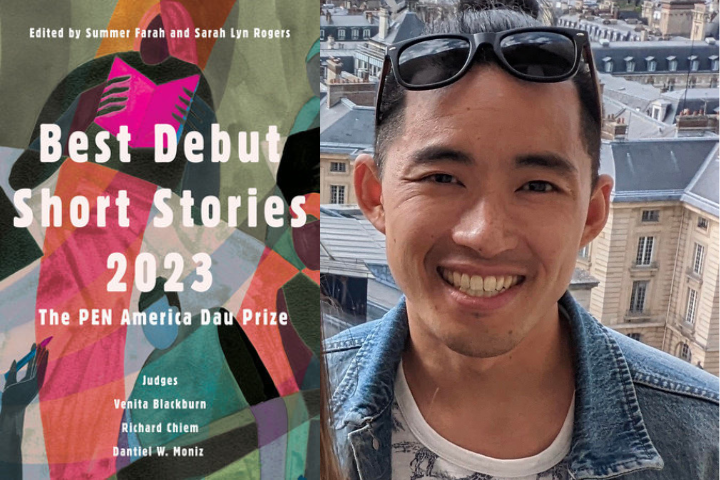

In the coming weeks, we will feature Q&As with the contributors to this year’s Best Debut Short Stories anthology, published by Catapult. These stories were selected for the 2023 PEN/Robert J. Dau Short Story Prize for Emerging Writers by judges Venita Blackburn, Richard Chiem, and Dantiel W. Moniz.

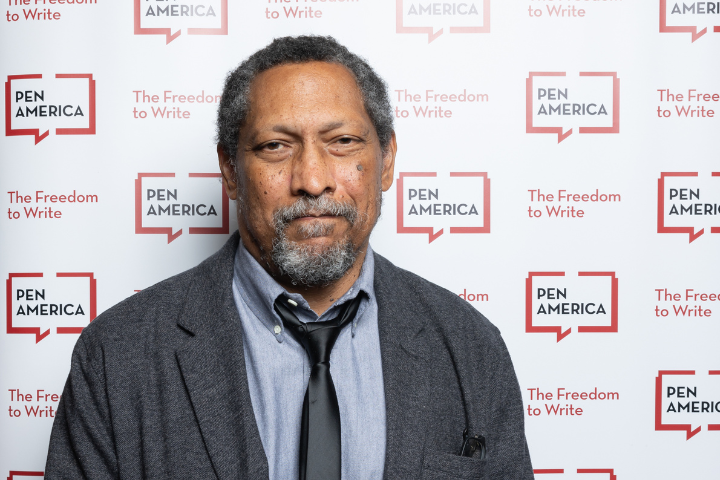

A program evaluator at the FDA, Patrick J. Zhou lives in Washington, D.C. with his wife Joy, newborn daughter Naomi, and their cat Bobby Newport.

“Tàidù” was originally published in Carve Magazine.

Here is an excerpt:

A pristine azure sky. Hugging the mountain range as far as Jia could see, a leafy quilt of emerald, canary yellow, and red. Tall trees in the valley bowing to gusts like worshippers to a throne. A glassy pearl of a lake gleaming in the late afternoon sun. A paradise. Here it was, the great natural wonder of the Middle Kingdom, the pride of his father’s province.[…]He reached his hand over the small gap at the top of the window to feel the breeze. He wanted to soak in as much detail as he could.

A lot of uncomfortable feelings are navigated in “Tàidù”; frustration, guilt, embarrassment, alienation…This is a lot for Jia to deal with during what was meant to be an emotionally significant moment. How do you go about writing this malaise?

Carve’s namesake, Raymond Carver, said “A little autobiography and a lot of imagination are best.” “Tàidù” was a result of scattered insecurities from whenever I visited my family in China (also where I was born) and a neurotic imagination. In writing characters, I turn the dial on my neuroses all the way up. Then I drop them someplace uncomfortable. Or make them vomit.

What inspired you to write this story? Where did the idea come from?

My graduate degree is in theological bioethics where I studied a lot of end-of-life decision making. In those situations, final choices reveal a lot about us—our character, our ultimate goals and interests, and how, what, why we believe. It’s fascinating to interrogate how people arrive at individual decisions and that’s pretty much what I did for Jia.

Another thing that interests me is how groups validate (or invalidate) identities. For my and Jia’s part, I fear both not being able to justify where I belong and not knowing who’s supposed to validate/de-impostor me. Who gets to say when someone is man enough, immigrant or native enough, person-of-color enough, American enough, dogmatic enough? There’s no lack of people laying claim to that authority.

Even in the process of writing “Tàidù”, I experienced this meta-dilemma. Would a contemporary Chinese person actually speak like this? Would a rural Sichuanese tour guide actually do that? I’m still only about 47% sure. What makes a character or person believable?

What do you hope readers take away from your story?

One thing, despite the melodrama—its humor. Hope and laughter go hand-in-hand for me.

Another thing—I’d love for people who read my work to walk away with better questions. I’m a firm believer that to get less and fewer hollow answers, we need to ask better questions. Of ourselves and others. Be gracious and curious.

How has the PEN/Robert J. Dau Prize affected you?

First of all, I’m indebted to the Dau foundation and judges Venita Blackburn, Richard Chiem, and Dantiel W. Moniz for making this all possible, and to the team at Carve for believing in my story. It’s an incredible honor, not only to be regarded by the judges but then to read the other fantastic winners was truly humbling. They front this rock band and I’m just happy to play back-up triangle.

I don’t have any degrees in English and my last college course in writing was freshman year 16 years ago (oof) so my impostor syndrome runs deep, especially when it comes to my writing. This limits my capacity to believe in myself sometimes; everyone else seems more well-read, better-trained than I am. As “Tàidù” attempts to capture, my tendency is to feel like I have to prove myself to someone, always. Winning the prize was a dream come true; at the same time, I haven’t let go of that insecurity. Paradoxically, this honor reminded me that if that kind of external validation is my prime motivation, I’ll never feel satisfied. The prize helped me reflect on what I want out of writing, out of publishing, and appropriately contextualizing it among everything else that’s also precious to me so that I can keep writing in a way that’s healthy and sustainable.

I hope I don’t sound like a jerk. I am humbled and super grateful. As of this writing, I have a one-week old daughter so I’m delirious most of the time, constantly baptized in poop, and reserve the right to take back everything I’m saying.

What advice would you share with aspiring writers?

If you insist being a writer means publishing (I disagree), then I’d say read. A lot. Flannery O’Connor, a major influence on my work, said, “the individual writer will have to be more than ever careful that they aren’t just doing badly what has already been done to completion… Nobody wants their mule and wagon stalled on the same track the Dixie Limited is roaring down.” Reading helps me thresh what’s been already said from what I might be able to offer readers that’s new or different.

And start with my fellow winners and this collection. You won’t regret it.