When I lived in Egypt more than 15 years ago, I knew a gentleman who regularly ran in local elections. He never put any work into a campaign or hoped to win office, but he ran, nonetheless, and thus gave his opponent the appearance of having real competition.

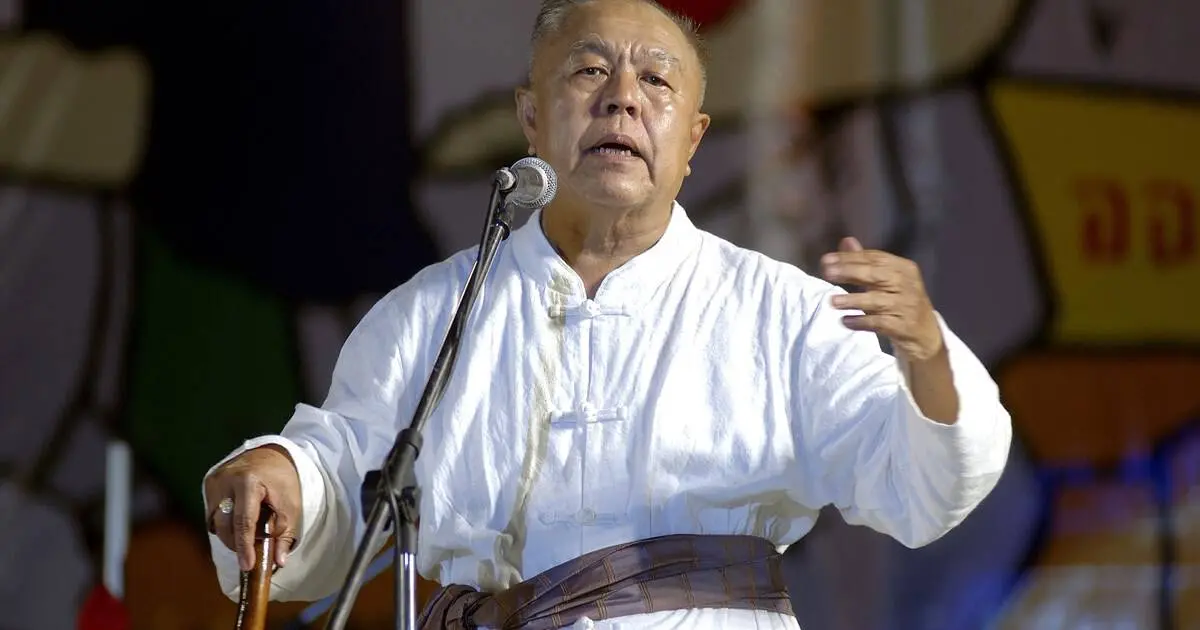

Today Egypt is preparing for a presidential election that will—like nearly all those before it—follow this same model. During the elections that will take place from March 26–28, Egyptians will have the opportunity to choose between incumbent President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and Moussa Mostafa Moussa, the chairman of the Al-Ghad party who was, until the day he announced his candidacy (after every other intended candidate had withdrawn or, in the least subtle case, been arrested), actively campaigning for Sisi. The outcome, of course, is all but guaranteed.

The veneer of democracy in Egypt has always been thin, but since the rise of Sisi, only the most half-hearted effort has been made to keep up the façade. Since he first appeared as a significant figure in 2013, following the military coup that ousted President Morsi, Sisi has overseen a brutal, unrelenting attack on human rights in Egypt, starting with his role as minister of defense during the violent dispersal of protesters from Raba’a Square in August of 2013, which resulted in the deaths of over 1,000 civilians. Since his election to the presidency in 2014, freedom of thought, freedom of assembly, and freedom of expression have been routinely assaulted under the guise of fighting terrorism or establishing “stability.”

Under Sisi, Egypt has put tens of thousands of political prisoners behind bars, and 20 journalists were in prison as of the end of 2017. The November 2013 decree known as the “protest law” essentially ended mass protests in Egypt and made even relatively small gatherings—if carried out without police permission—too risky for all but the most dedicated activists. A national state of emergency in place since April 2017 was extended for another three months in January. Criticism is portrayed as a threat to national security and public order, and the media and other detractors are quickly labeled as “members of an outlawed group”—code for the Muslim Brotherhood, the regime’s bogeyman of choice since the military regained power from Morsi in 2013. The result is an environment in which the free expression of political views or preferences by citizens or even politicians is virtually impossible. By definition, an election that takes place in such a context can be neither free nor fair.

Not content with that degree of control, however, the regime has doubled down on crushing free expression in the run-up to the election and has sent a clear message to citizens—and journalists in particular—that dissent will not be tolerated.

Perhaps to ensure that Egyptians in exile would not be too vocal as the elections neared, amendments to Egypt’s Nationality Law were proposed last fall that would broaden the state’s ability to revoke citizenship based on individuals’ views, political affiliations, or associations with international organizations. If passed, the amendments would grant the government a terrifying power to chill the speech of Egyptians in or outside the country; and while proposed legislation in Egypt often moves slowly, in the meantime, it looms as a still-powerful threat.

Access to information within the country has been targeted throughout Sisi’s tenure, with nearly 500 websites blocked in Egypt since May 2017; but this targeting rose to a new level in early February, when authorities blocked the Accelerated Mobile Pages (AMP) project, a tool for mobile content delivery, and therefore blocked Egyptians from using their phones to reach websites like those of CNN, The Guardian, or The New York Times.

Attacks on journalists and local or regional media have increased, too, and in the past month the warnings have been made particularly plain. Three different journalists—Moataz Wadnan of HuffPost Arabi and Mostafa al-Asar and Hassan al-Banna of Ultra Sawt news website—went missing in February and reappeared in custody shortly thereafter. Wadnan was arrested after he interviewed an aide to Sami Anan, the aspiring presidential candidate who was arrested in January. Perhaps unnecessarily, given the broader climate, guidelines have been issued for media coverage of the elections, prohibiting journalists from asking Egyptians how they intend to vote or conducting any exit polling.

Given this effort to control the pre-election environment, it is no surprise that the government’s fury was sparked by a February 23 BBC report on disappearances, torture, and attacks on the opposition in Egypt, with authorities calling for a boycott of BBC and declaring the report to be Muslim Brotherhood propaganda. On March 2, it was reported that authorities arrested the mother of a young woman featured in the report, Zubeida, who disappeared in April 2017. In the report, Zubeida’s mother details the torture and abuse she and her daughter faced at the hands of police during a previous detention, and insists she will not stop speaking out until her daughter is freed. Days after the report’s release, in a bizarre twist, Zubeida appeared on a talk show on a pro-government TV station, denying the reports of mistreatment; her mother maintains she was forced to do so.

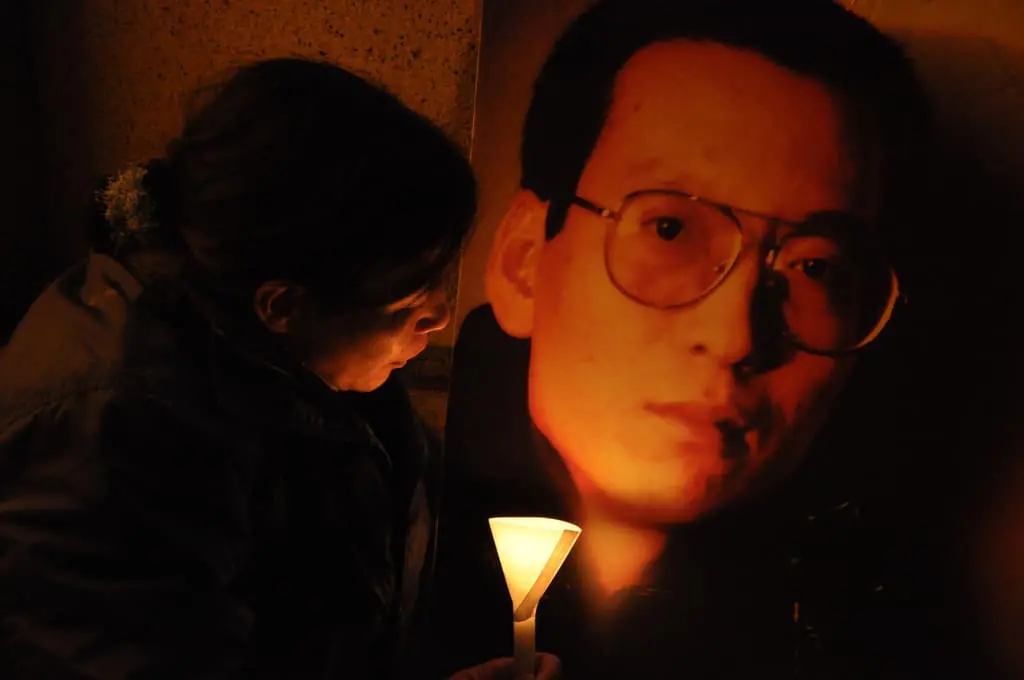

Shortly after the mother’s arrest, Ezzat Ghoneim, the prominent human rights lawyer who was handling her case—as well as Wadnan’s—went missing as well, turning up on March 4 to be interrogated in front of the State Security Prosecution. That was a day after prosecutors requested the death penalty in a mass political trial that includes the photojournalist Mahmoud Abou Zeid, known as “Shawkan,” who was detained in 2013 while covering the massacre in Raba’a Square and who could now be executed for his work as a journalist.

Short of such extreme risks, the BBC report itself demonstrates why even the brief disappearance of journalists and other critics can be such an effective threat; as its subjects relate, disappearance often means torture, and while some people reappear promptly, others are lost for years, their families left to wonder and wait.

The controversy around the report has also given the government a timely and convenient excuse to make fevered claims about the danger of the “broadcast and publication of lies and false news” by “forces of evil,” as the public prosecutor said in a statement on February 28. He followed by instructing prosecutors to pursue legal action against media outlets that “disseminate false news statements or rumors that could instill terror in society, hurt the public interest, or disrupt peace.” Prosecutors wasted little time, ordering the detention of a pro-government television host while authorities investigate a segment on his show deemed potentially “harmful to the police” because it included reports that the wife of a police officer had complained about her husband’s salary.

The lead-up to the elections has coincided with a ramped-up attack on Islamic State-affiliated militants in the Sinai Peninsula. On March 1, Sisi declared that any criticism of state security forces would be considered “high treason,” saying such language was “no longer a question of freedom of speech.”

He is correct about that. For Egyptians who oppose the regime, there is no freedom around speech—there is only the question of what you are willing to risk. In an election, that means there is no choice, and the international community must not pretend this one is anything other than a sham. We know Sisi will win, but it is Egyptians who will lose.