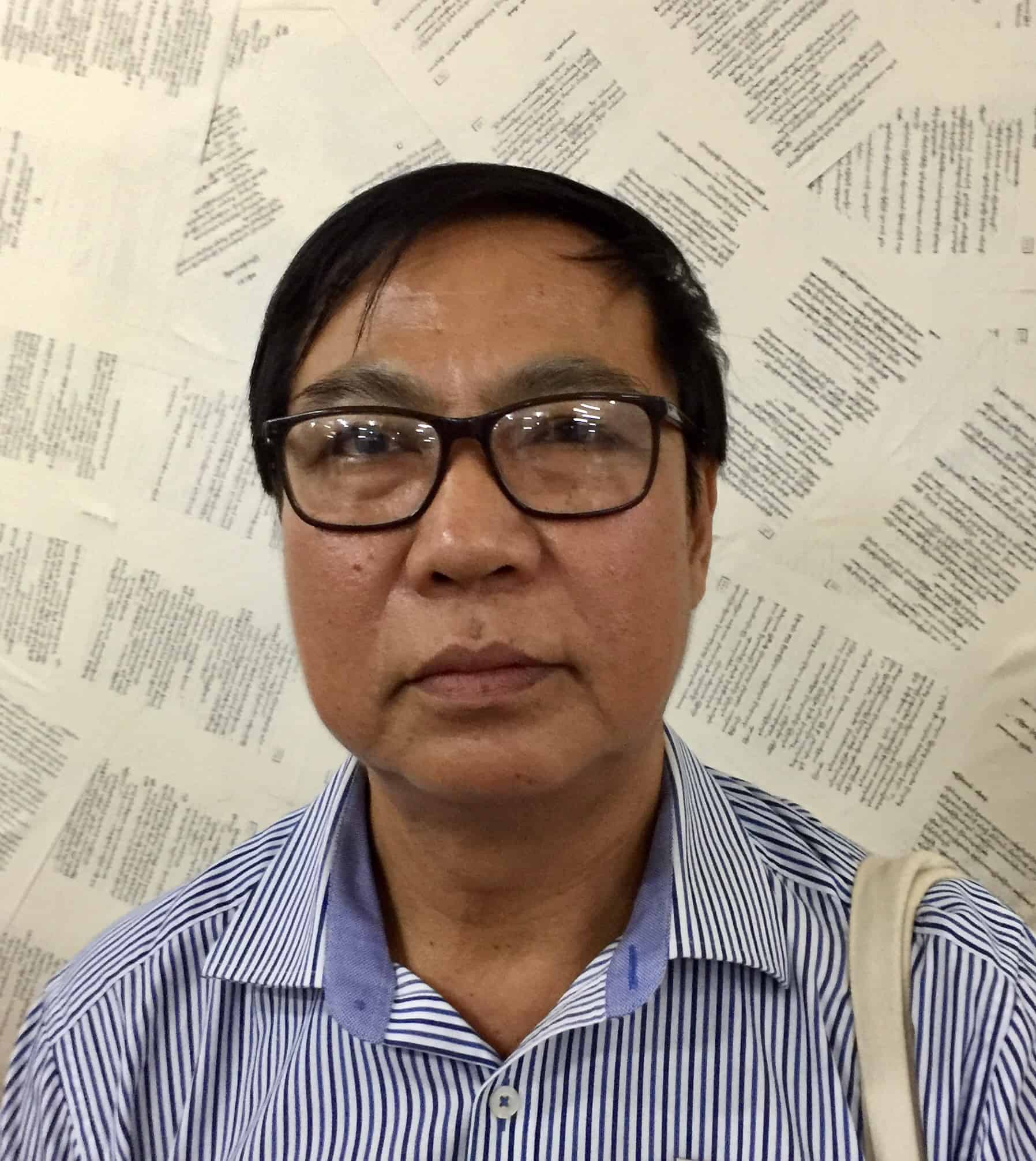

Since Myanmar’s military seized power on February 1, it has employed increasingly sophisticated digital modes of repression, alongside physical and legal measures, to try to stem democratic resistance. As Allie Funk of Just Security has written, we are witnessing a digital-age coup. Myanmar’s military has a long history of violating human rights, including freedom of expression and the right to privacy, but this time around, the military’s digital repression is dramatically more sophisticated. As the situation continues to worsen, the people of Myanmar are also showing their own sophistication in digital resistance. Information about what is occurring in Myanmar is rapidly evolving, at times scarce, and sometimes anecdotal. Here we summarize what we know about some of the most important digital threats:

Fixed-line and fiber internet services recently came back online after 72 nights of near-total shutdown, but mobile data, wireless broadband, and social media platforms remain heavily obstructed. While this means that users can now directly connect to the internet through a cable, it is uncertain how long this will be available and whether or not the junta will turn wireless broadband back on. Mobile data has also been disabled in the country for more than 50 days. Restrictions on mobile and wifi access also increases security risks for users as they communicate, as many circumvention and online safety tools work primarily as applications on mobile phones.

On the fourth day of the coup, the military ordered telecommunications providers to block Facebook, a platform practically synonymous with the internet in Myanmar, and Facebook-owned platforms such as WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook Messenger. Many people, including journalists, continue to lack access to social media. Yet even when the internet is not fully shut down, people have been reporting slow internet speeds. It is unknown whether these are intentional delays or side effects caused by damaged infrastructure.

Internet blackouts are nothing new in Myanmar and have been a commonplace technique used by the government to target ethnic minorities and for political ends. In June 2019, the government imposed a mobile internet shutdown, cutting off internet access to people living in Rakhine and Chin states for more than a year, making it the world’s longest internet shutdown, with some villages completely unaware of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now it appears that the junta may be seeking to consolidate power, in part, by trying to keep the internet “on” to support economic activity, but also keeping connectivity limited and surveilled to control free expression, democratic participation, and protest.

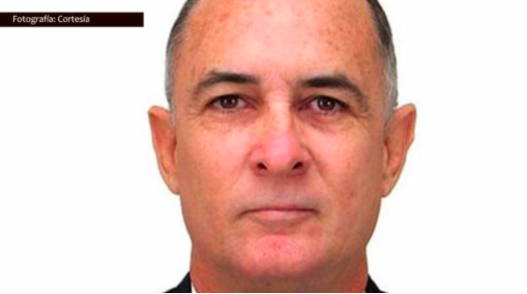

Reliable news—both about the coup and the pandemic—remains scarce online. Journalists continue to face surveillance, internet blackouts, and confiscation of their mobile phones. Disinformation is filling the void. There is great uncertainty about what information online is true and according to journalists, the flow of news “has almost stopped.” It’s been harder for reporters to verify facts as people are increasingly scared to talk to the media or use their real names and the military is clamping down on those using phones to record events. The junta also recently banned all satellite television, which some Burmese outlets were relying on as a last resort to reach their audience, and will present further hazards for the public in accessing foreign news. While citizens in cities have developed ways to share information offline, in some villages, being cut off from the internet has resulted in an information vacuum, with rumors spreading quickly and easily. Months before the coup, Myanmar was already facing a flood of disinformation and fake news leading up to the presidential elections, which may have helped lay the groundwork for the coup.

Though tech companies have vowed to filter pro-military content on social media, the military has weaponized platforms to spread terror and messages of violence. Although Facebook, TikTok, and YouTube have all vowed to remove propaganda and misinformation published online by the military—and even banned military and military-controlled state accounts—soldiers have been posting pro-military videos on TikTok, including statements such as, “I will shoot whoever I see” in their videos. In response, on April 14, more than two months after the coup, Facebook announced that it will remove any praise, support, or advocacy of violence by Myanmar security forces on its platform. The military has also reportedly used “deepfake” manipulated videos to try and discredit the previous government.

The military is using Chinese-made surveillance technology to track and intimidate protestors and those engaged in resistance. In December 2020, Myanmar’s government installed hundreds of surveillance cameras in the capital Naypyidaw and in Mandalay. The technology was supplied by the Chinese company Huawei through their “Safe City” initiative—the Chinese government has used similar Huawei technology to target the Uyghurs in Xinjiang and has supplied it to other countries around the world. Equipped with facial and license plate recognition technology, the cameras can automatically alert authorities about those on “wanted lists.” This sophisticated surveillance infrastructure is being used in tandem with unmanned Chinese-made drones, deployed by the junta to monitor and intimidate protesters on the ground. Russia’s government has also supported the junta, providing more than $14 million in air missile systems, surveillance drones, and radar equipment in February. One result of this surveillance architecture is increased anxiety about preserving anonymity among the public, which is chilling speech and public protest.

The junta has now legalized surveillance and expanded the government’s powers to intercept electronic and written communications. The junta’s changes to the Law Protecting the Privacy and Security of Citizens mean that the government now has the power to detain arrested individuals indefinitely without judicial oversight. Under this law, the junta has also suspended a number of privacy protections, giving the government power to conduct searches and seizures without civilian oversight and to surveil and intercept citizens’ communications, including electronic data. This has created an increasingly dangerous atmosphere, as the government carries out night raids during which hundreds of people have disappeared. The junta’s amendments to the Electronic Transactions Law have also broadly expanded the government’s powers to criminalize digital activity and social media posts and acquire personal data. The government now has unhindered access to personal data and the ability to arrest individuals for any online activity that “cause[s] public panic.” In this law, “fake news” and “false news” are not clearly defined, leaving wide room for interpretations of “criminal” digital activity that could result in convictions and up to three years in prison.

As tensions on the ground between the military and protesters continue to escalate, it is clear that the junta is taking steps to consolidate their power and establish a functioning economy while maintaining the ability to censor. They are essentially building a “walled garden” of internet services, in which the military will decide what content can be accessed and by whom. To many, this has echoes of the censorship board that heavily monitored and censored news, and which was eventually disbanded by President Thein Sein in 2012.

Despite all of this, the people of Myanmar continue to show creativity and persistence in their resistance to the junta. After the junta started blocking some internet circumvention tools, such as some virtual private networks (VPNs), Myanmar citizens adopted others, including tools that use alternate protocols and close-range communications that don’t rely on the internet. Others are evading restrictions by using foreign SIM cards and by sharing radio frequencies or sending SMS messages, which don’t use data services but can present their own security challenges. Overall, there has been a sharp rise in the use of circumvention tools and alternative forums within the country as activists attempt to remain connected.

Activists are also seeking to put the junta on the defensive. Despite the odds, documentation of abuses and journalism from inside and outside the country continue. In a story-telling project supported by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting, some students are being trained in producing short films to capture ongoing protests and rights violations. And since internet and social media connectivity remains limited within the country, many individuals in the U.S. and in the overseas Myanmar community have become involved in the resistance, organizing via social media, video conference, and other tools, calling out the junta and demanding action from the world.

PEN America continues to stand with the people of Myanmar and the protection of digital rights. You can follow updates on what is happening in Myanmar and express your solidarity with the hashtags #WhatsHappeningInMyanmar and #SaveMyanmar.