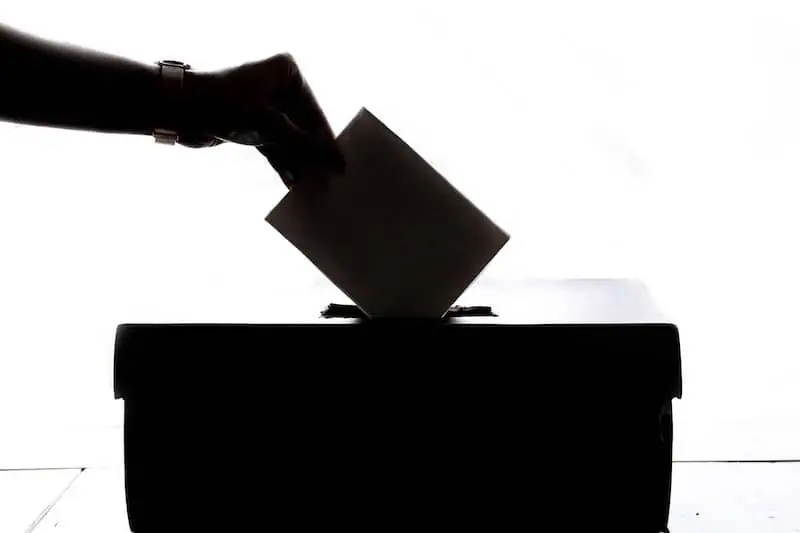

In a recent presidential election in Belarus, widely believed to have been rigged, longtime incumbent Aleksandr Lukashenko claimed victory with 80 percent of the vote, entering his sixth term as the country’s leader. This sparked nationwide protests, as well as gross human rights violations by the police, including arbitrary detainments of protesters and incidents of police brutality. We support our colleagues from PEN Belarus and all Belarusian people in their struggle for their freedom and other fundamental rights. Today, we publish a piece by Tatsiana Zamirovskaya, a Belarusian writer and journalist currently living in Brooklyn.

“Girl, this is your last chance to have tea with Hitler”

I collect dreams about dictators. My main interest, though, is collecting the dreams Belarusian people have about their dictator. Officially, from a psychoanalytical point of view, authority figures in dreams manifest our superego—the moral and controlling part of ourselves—but for Belarusians, it’s different. Dream Lukashenko is their silent neighbor and stalker who scolds them, gives useless advice, exhausts them with demagoguery, rapes them, and transforms himself into a duck to retire peacefully in California.

My goal is to create a somnological portrait of Lukashenko in the Belarusian collective subconscious. Who is he to us in dreams? It seems the country has been sleeping for 26 years—and now that it seems to finally be rising from this sleep, it’s a perfect moment to ask: In the sleep of oppression, what dreams may come?

I’ve collected more than 200 dreams. Some I found online; some were sent by fellow Belarusians, often with a therapeutic motivation. Recently, when I met some Belarusians at the New York consulate, instead of “hi,” some of them immediately said, “Well, you collect those dreams, can I share mine?”

A lack of communication with the government reflects itself in dozens of “confession” dreams: When Belarusians meet Lukashenko in their dreams, they tell him literally everything they think. Maybe it’s dream therapy as well—to finally speak out, unafraid.

“I had a dream that I was riding my bike in a park and saw Lukashenko. He was also riding a bicycle. I yelled: ‘You dick!’ and fled on my bike, followed by riot police.”

When a dreaming Belarusian finally tells Lukashenko what they think, nervous breakdowns happen—people actually cry in their sleep.

“I had a dream of Lukashenko throwing little pieces of bread into the crowd. And I was crying because of his cruelty and the poverty of Belarusian people, and I called him Hitler.”

“I have a recurring dream where I find myself at an official reception at Lukashenko’s, as one of the guests, and start to make complaints about his work, and more importantly, about perpetrated violence. I say ‘shame on you,’ ‘could you finally just leave,’ ‘how long can we stand it,’ and ‘stop it!’ Then I start to cry, and I wake up in tears, screaming, or with clenched teeth.”

“After he discussed integration with Russia and the roadmaps, I was very worried, so in my dream I was sobbing and asking him what the name of our country will be from now on. He turned his face away, lowered his head, and was silent. I was so scared and terrified that I woke up.”

Their dreams mostly had the same plot: Lukashenko was giving a speech in front of them, while they were hastily looking around to hopefully find any device to kill him: “I saw him and realized—he is a strong, huge man, so I thought, maybe there is a pen on the table. If it’s a metal one, it may work.”

“I was overthrowing Lukashenko in my dream today,” my friend wrote to me. “By shooting him and his men with a nice-looking gun. During little breaks, I was listening to New Order on vinyl.”

It seems there is a little Lee Harvey Oswald napping inside every sleeping Belarusian—as we know, he lived in Minsk for quite a while. There are so many assasination dreams in my collection that I’ve realized I can’t publish it in Belarus.

Dream Lukashenko is invading people’s homes: He is eating with them, sleeping with them, he is literally everywhere. Maybe this is learned helplessness—when a Belarusian enters his home, he never knows if a dictator is there, spying and eavesdropping. He behaves like an unwanted relative—that annoying embarrassing old uncle—whom nobody wants to see, but once a year we have to pretend to have a sweet family reunion.

“We sit in our kitchen—me, my wife, and A.G. Lukashenko, having breakfast. Lukashenko brags about the good harvest this year—actually not very good, because 80 percent of this harvest he had to buy from his neighbors. We start trolling him, like, can you really call it a good harvest if you had to purchase 80 percent of it from your neighbors? And then I look at everyone and say: ‘Hey guys, it’s the first time ever the whole family is finally at the table, having breakfast! So let’s just not talk about politics, at least at the table!’”

Sometimes, Dream Lukashenko harasses people in their homes, just like in the movie It Follows: silent and inescapable, like a shadow.

“He stalked me all night. He followed me in the woods, then in my apartment, then followed and stalked my cat. He was dressed up in a suit (Lukashenko, not my cat), then I met him at the grocery store and he followed me, then I went to bring the garbage out and he was there again.”

“I only remember one thing: He kept following me everywhere with a fish. He had, like, a fish with him, in a tiny fish bowl. Then we negotiated that he would release the fish.”

In most dreams, he is literally dictating and oppressing, giving advice on everything. In one dream, he was giving advice on “how to rule the country,” in another “he taught me how to make proper macrame knots.” Another dream has marvellous advice on how to spot the opposition:

“I saw Lukashenko in my dream. He was cool and chill. Said that those people who drain juice from shredded potatoes before shaping a dranik [the national Belarusian food, a potato pancake], are more likely to join the opposition.”

A hopeful thing is that there are also dozens of dreams where he is afraid and hiding, trying to escape from Belarusians who are there to arrest him.

“I am in some apartment with my kids, also there is George Clooney auditioning Lana Del Rey at the beginning of her career. And there is Lukashenko hiding in the next room. He is very stereotypical—a huge man wearing oversized linen clothes, like a peasant, with a rope belt. He sits on the floor freaked out, hiding from someone. We are freaked out as well because we did not want him in this apartment, but somehow ended up being there with him. . . Afterwards, he panics and finally runs away to hide somewhere else. And he threatens me with a gun, wrapped in another linen shirt, saying, ‘You will be the first to blow your brains out.’”

Sometimes, after finding Lukashenko in their apartments, Belarusians pity him and hide him, or like this young mom, let the exhausted old dictator have a little rest:

“He was at our apartment giving a speech from the second floor, then he said he was tired and wanted to take a nap, and he would leave after he took a little rest. He went to my room and slept on my bed, under the blanket, not removing the throw. I asked him if I could open the window slightly, for him to have some fresh air, but he said, ‘Just a bit, otherwise I will get cold.’ I went to put my daughter to bed in her room; after that, I was silently cooking oatmeal for my daughter in the kitchen, and then he appeared after his nap. I asked him if he wanted some oatmeal, and he didn’t refuse. I put some oatmeal for him in a cup and kept cooking, and we kept talking. I am pregnant now, so I am thinking—can all that mean that I should name my kid Sasha if it’s a boy?”

Lukashenko’s iconic mustache is also featured in dreams—in several dreams, he shaves it off, finally.

“He shaved off his mustache and was unrecognizable. And was wearing jeans and sneakers. We went to a club to pick electronic mushrooms from, like, you know, some table—like a gaming table.”

“I saw Lukashenko in my dream today. His mustache was shaved off unevenly. He said he will abolish the death penalty in Belarus through referendum.”

Someone saw Lukashenko in dream with Hitler’s mustache:

“He had the same mustache as Hitler. He was very gloomy and was eating black pierogi with sour cream.”

Another mustache dream is very inspiring and can be used as a positive affirmation in specific circumstances:

“It happened when I studied in Vilnius. I had an unhappy love affair, so I didn’t study and just was stuck in drama. So I dreamed of Lukashenko (I saw only his mustache, and it was moving, very huge, taking up the whole frame like in movies), and he said: ‘Stop it! Just go work in the field! Work on your land, just like your president!’ So now, every time when I feel fatigue and depression rolls over me, I repeat this instruction to myself.”

Maybe because of Lukashenko’s mustache, Belarusians have many dreams featuring Hitler. One of them is very convincing:

“In my dream, me and my friend were invited to the opening of a new subway line in Minsk. So there is the first train—long, white, made in Germany. Lukashenko and the train driver lady emerge out of it, and he says to her, ‘A good train, now please ride it to the end of the line, but come back in 20 minutes, to meet the train of the German delegation. Girl, you should understand this is your last chance to have tea with Hitler! He has some candies he brought, very sweet. He is very old, there won’t be another opportunity.’”

I personally also had a scary dream about Lukashenko and candies. He met me at the Belarusian consulate in New York, holding two vases with Belarusian candies made at the Kommunarka factory. He stopped me and said reproachfully:

“You all scold me for what I am doing now, like, how could I, how bad I am! Like, he distributes the state treasury to his sons! But I will never take what’s not mine. And I will never take what belongs to my people. Now look—in this vase there are state candies, bought with tax money. Those are the people’s candies. I will never touch them. And in that vase are candies that I myself bought with my own salary! If I need candy, I only take from this vase.”

To confirm his words, Lukashenko took one candy from the “people’s” vase, and the other from his personal one. And he held out both to me:

“I can give you two candies—one from the personal vase and one from the people’s one. Because you are the people. Do you understand?”

I took two candies given to me by Lukashenko—they were identical, and I quickly forgot which one was the people’s— and left. I knew that I had to go to a tiny shop outside the embassy and exchange candy for money there; it was the reverse purchase ritual.

Dream Lukashenko not only gives out candies, but also loves transforming into women—many dreamers actually see him dressed as a woman—or just putting on a dress. Someone saw him pregnant in a dream (“Well, now I know how he managed to have a kid without a wife,” he mentioned), someone saw him as a “dwarf who was for some reason upset with me.” Somebody saw him as a cute duck.

“Has anyone else seen Lukashenko as a duck in a dream? I had such a dream today. It was not even an image. There were just 3-4 cute ducks swimming over there, and I suddenly understood one of them is special. After that, my subconscious said to me that it’s Lukashenko.”

But not all animalistic representations of dreamy Lukashenko share this level of cuteness: “I saw Lukashenko in my dream. He looked like a spider, was looking for oil, and was living in my hair.”

Belarusians sometimes dream about revolution—“I asked my friend why there were so many of the banned white-red-white flags everywhere. He replied: Haven’t you seen CNN? Lukashenko has finally been arrested. Because he was threatening his people with tanks! And before that, he shot 700 people, when there was the first protest.”—but mostly in their dreams, they try to crack the mystery of Lukashenko’s power:

“Once, I dreamed that Lukashenko created the magical seven-dollar bill, which helped him to gain total control over Belarusian people.”

Sadly, there also were many dreams about sexual harassment, abuse, and rape. Women who told me about those dreams confessed really reluctantly, as if it were an actual traumatic experience.

“I feel terribly ashamed. . . it was an erotic dream. In fact, sex with him.”

“. . . he said: ‘Let’s do it for our homeland and independence!’ After it, I felt terrible, self-loathing, and self-disgusted, for I could not even resist—as if I were a shabby dirty rag. And he just said, just like Charles Manson: ‘You are all my children.’”

“We were at some wooden residence. He showed me the way and then piled on me with all his weight and. . . well. . . I remember just his heaviness, his heavy breath, and that it was difficult to escape.”

In my dream collection there are also dreams about death, but not all of them feature assassination. Sometimes, he just appears injured—with a fractured skull, or shot in the eye. Again, psychoanalysis tells us this means nothing but the initiation of a dreamer—one’s desire to get rid of the controlling, dictating part of oneself. But anyway, the Belarusians are so nonviolent that they sincerely pity Lukashenko in those dreams.

“I had a dream that Lukashenko was shot. And I felt really bad for him.”

But most of the “death dreams” have nothing to do with psychoanalysis. In fact, they might reflect the Belarusian pagan, pre-Christian subconscious, based on the old cult of reverence for dead ancestors, so-called “dziady” (the granddads). There were several eerie “granddad” dreams in my collection.

“We are at the cemetery, remembering Grandma and Grandpa. Suddenly he emerges, opens the gate, comes in. We pour some vodka for him. He quickly drinks it in one gulp and says that my granddad was a good man. I understand that I urgently need to ask him something, but I can’t open my mouth, and he looks at me and threatens me with a fist.”

“I had a dream that I am visiting him in jail. But the prison is inside my dead granddad’s pig sty.”

“I stopped some car, and there was an old babushka inside. She was a witch. She started to tell me things about myself, all true. And then she says, ‘Lukashenko will die in two years.’ And I ask her, ‘What year is it?’ But she is silent. And I yell to everybody in a car, ‘What year is it?!’ But everyone is silent.”

But not all dreams end up this way. In some of them, the dictator retires happily to start on a career as a stand-up artist, or moves to California. The “California dreaming” part of my dream collection sounds hopeful: “In this dream, we lived in California, and he was our neighbor. There was a huge hedge, and we climbed onto it to watch Kolya, his son, swimming in the pool. Instead of Kolya, I saw HIM in the pool and thought, ‘If he starts to drown, will any of us help him?’ And then we thought, ‘There is no need to hold grudges—the guy retired and moved here to live his final years peacefully.’”

Now I helplessly browse through my dream collection thinking it could be used for reverse dream reading: The current political situation in Belarus can be interpreted with those dreams, which are much less surreal and weird than what is actually happening in my homeland.