New Wave of Higher Ed Restrictions Goes Beyond the Classroom to Restrict Entire Curricula

Monthly Roundup, April

This post is part of a series from PEN America tracking the progress of educational gag orders and censorious legislative efforts against educational institutions nationwide. These bills are tracked in our Index, updated weekly.

Two new educational gag orders were adopted in March, and two more in April. After reviewing these gag orders in this month’s Roundup, we examine a troubling new trend in censorship legislation that affects higher education: a shift from bills that ban lists of so-called “divisive concepts” in classroom instruction, toward a new class of bills that specifically restrict the content of curricula, including majors, minors, and general education. Not only are these new bills equally censorious compared to the older model, they are more brazen and have the potential to be much more destructive to the basic functioning of university life.

- Since January 2021, 306 educational gag order bills have been introduced in 45 different states

- 22 have become law in 16 states (3 are not currently in effect)

- 2 additional states have enacted educational gag orders via policies or executive orders

- 118 million Americans live in the 18 states where an educational gag order is in effect

- 87 educational gag orders are currently live

Of those currently live:

- 78 target K-12 schools

- 25 target higher education

- 40 include an avenue for punishment for those found in violation

New Laws and State Policies

March:

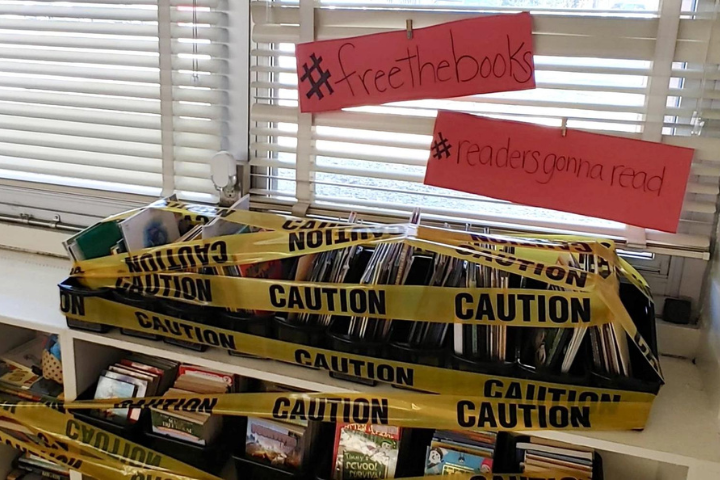

- Utah’s HB 427 prohibits public K-12 schools from providing to students any instruction or curricular materials such as books or other media that is not “consistent” with certain “principles of individual freedom” related to race, color, ethnicity, national origin, religion, disability, sex, or sexual orientation. Public schools are also prohibited from attempting to persuade any student or school employee to adopt “a point of view that is inconsistent” with these principles.

- Arkansas’s SB 294 forbids public K-12 schools, as well as their contractors and guest speakers, from intentionally or unintentionally promoting “Critical Race Theory.” The law also prohibits any school communications or materials that compel individuals to adopt or affirm certain concepts related to color, creed, race, ethnicity, sex, age, marital status, familial status, disability status, religion, or national origin. Schools may not provide classroom instruction related to sexual orientation or gender identity to students in grades K-4.

April:

- North Dakota’s SB 2247 prohibits public colleges and universities from asking students about their “ideological or political viewpoints.” No state funds, excepting regular salary or compensation, may be used to incentivize a faculty member to incorporate certain ideas related to race, sex, religion, creed, nonviolent political affiliation, social class, or any other class of people into an academic curriculum.

- Florida’s State Board of Education adopted a policy to prohibit public K-12 schools from offering any classroom instruction related to sexual orientation or gender identity to students in grades 4-12, unless such instruction is expressly required under state standards or as part of a health course.

From Classroom Censorship to Curricular Control

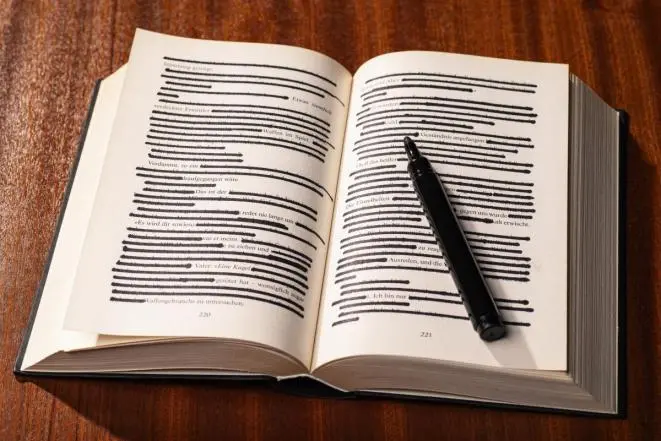

For supporters of educational gag orders in higher education, this has been a year of setbacks. Since 2021, their greatest victory to date has been the passage in Florida of HB 7, also known as the Individual Freedom Act or the Stop W.O.K.E. Act, which prohibits faculty in public (and potentially private) colleges and universities from providing any instruction that “espouses, promotes, advances, inculcates, or compels [belief in]” certain ideas deemed discriminatory by the state. In both structure and purpose, the law is a naked attempt to suppress faculty speech.

But in November 2022, a federal judge stayed these provisions, finding that they violated the First Amendment rights of individual faculty to express themselves in the classroom. It was a major defeat for gag order supporters, and has been followed in recent weeks by the failure of similar bills. Utah’s HB 451, which failed to pass in the state Senate, would have barred public college and university faculty from asking students their opinions about “anti-racism,” “implicit bias,” and “critical race theory” as part of any course or degree requirement. In North Dakota, HB 1446 was amended to remove provisions implicating faculty speech, before it also failed to pass. And in West Virginia, where last year lawmakers came within minutes came within minutes of passing a higher ed gag order, this year’s version died a quiet death in committee.

Unfortunately, conservative policy analysts who support educational gag orders have taken note and are adjusting their strategy accordingly. One such analyst is Adam Kissel, a visiting fellow in the Heritage Foundation’s Center for Education Policy. In a December 2022 piece for The Federalist, Kissel offers what he calls “the smart lawmaker’s guide” to writing EGOs that will stand up in court. According to Kissel, legislators should stop trying to restrict the constitutionally protected speech of individual faculty members. Instead, they should target public higher ed where it is most vulnerable: at the level of curriculum. Writes Kissel:

Consider the subject of astrology. It would be reasonable for a department of astronomy, its university, or its state legislature to make a determination that astrology readings are an unserious waste of time. Accordingly, campus policy or the law may require that there be no assigned astrology texts, no astrology units, and no astrology courses at the university. None of this would prevent astrology from being discussed in the classroom incidentally, from any viewpoint. The point is that it will have no place in the regular curriculum.

The same is true for other subjects, including [Critical Race Theory]. A college department, a university, or a legislature may, as a matter of content and careful judgment, either require or prohibit modules, units, and courses on any topic. Further, the university or the legislature might determine that an entire program or department is not sufficiently valuable to receive scarce resources.

In other words, Kissel recommends focusing on academic structure instead of academic speech, proposing to prohibit or constrain whole areas of academic inquiry rather than target individual professors’ teaching. However, his plan would undoubtedly trigger widespread censorship. After all, if a faculty member knows that teaching the wrong lesson or researching the wrong topic might torpedo their department, that lesson and research will not happen. In Kissel’s estimation, any constitutional problems would be avoided; but the strategy would still quite clearly entail ideologically-motivated government censorship, even if in a different form.

Christopher Rufo, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute and leading EGO activist, recently made a similar claim, arguing that academic freedom only attaches to the individual faculty member, not the college or university as a whole, and certainly not to its constitutive departments or units. Rufo writes:

[It] is not a violation of “academic freedom” to close down ideologically captured or poor-performing academic departments; it is, to the contrary, part of the normal course of business. Legislators in states such as Florida and Texas, which will both be considering higher education reform this year, should propose the abolition of academic departments that have abandoned their missions in pursuit of shoddy scholarship and ideological activism.

Curricular Control Legislation

Neither Kissel nor Rufo is breaking new ground here. This sort of backdoor route to faculty censorship has a long history, and includes everything from targeted budget cuts to shuttering academic centers. Nevertheless, the efforts in 2023 are on a much larger scale. PEN America has begun cataloging these efforts, and others, in a special tab for “Higher Education Autonomy Restrictions” in our Index of Educational Gag Orders.

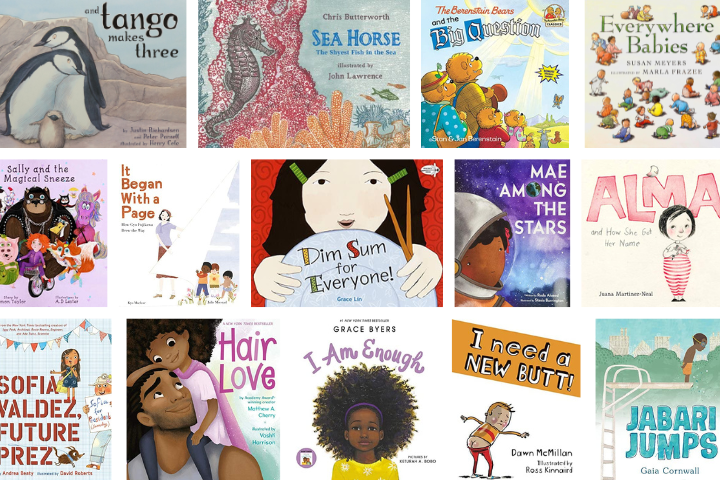

The most salient example is Florida’s HB 999, which is currently under consideration by the state legislature. As originally drafted, this bill would have required public universities and colleges to “remove from [their] programs any major or minor that is based on or otherwise utilizes pedagogical methodology associated with” certain disfavored academic theories like “Critical Race Theory” or “Intersectionality,” or that “includes or promotes” the concepts listed in the Stop WOKE Act.

This language was removed in a later draft of HB 999, but what has replaced it is hardly better: a ban on the use of public money for any “programs or campus activities” that violate the Stop WOKE Act or that “advocate for diversity, equity, and inclusion, or promote or engage in political or social activism.” The Florida Senate version goes even further, prohibiting programs and activities that are “based on theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, and privileges are inherent in the institutions of the United States and were created to maintain social, political, and economic inequities.”

Both House and Senate version would also prohibit colleges and universities from offering a general education course that “teaches identity politics, violates [the Stop WOKE Act], or is based on theories that systemic racism, sexism, oppression, or privilege are inherent in the institutions of the United States and were created to maintain social, political, or economic inequities.”

PEN America has seen similar proposals floated in other states. Earlier this legislative session, lawmakers in Wyoming considered but ultimately rejected a budget amendment to prohibit the University of Wyoming from using state or federal funds for “any gender studies courses, academic programs, co-curricular programs or extracurricular programs.” Other less explicit bills are likely preludes to something similar. Tennessee’s HB 1115 would transfer the authority to terminate academic programs from public universities’ Boards of Governors to the Tennessee Higher Education Commission, a body of lay people appointed by the Governor and General Assembly. And in Missouri, SB 410 takes aim at “DEI ideologies,” defined in the legislation as any topic dealing with “antiracism, implicit bias, health equity, and any other related instructions or that promote differential treatment based on race, gender, religion, ethnicity, and sexual preference.” If adopted, the bill would prohibit colleges and universities from requiring students to “answer any questions” related to these topics over the course of their studies. The chilling effect of such a law on faculty and student interaction would be wide – no doubt intentionally so.

Finally, there is North Carolina, where an exhaustive 2022 study by the American Association of University Professors revealed an out-of-control and politicized Board of Governors. Just last week, GOP lawmakers rolled out new legislation that would give the Board the authority to regularly evaluate and eliminate “unnecessary or redundant” areas of study. To help identify these areas, the bill also requires public colleges and universities to submit to the state legislature a report summarizing the research projects of faculty in each area of study, including how many hours they devote to their research and its cost to the state – a kind of individual-level monitoring of faculty activity that would be unprecedented and appears designed to chill and intimidate their academic work. This proposal is still live, cut from the same cloth as these other attempts to politicize academic decisions.

Rufo has described restrictions of this type as a form of populism: “reestablishing public ownership and public authority over our public institutions,” as he put it in a recent video. The public should express that “these are our values, and we expect them to be reflected in our public institutions, and we’re not going to keep paying money to things that are against our wishes.”

This argument is both wrong and profoundly dangerous. The University of Florida’s Biology Department should not reflect the ideology of the state of Florida or its government; it should reflect the discipline of biology, in particular what academic biologists believe to be a true and accurate account of their field. Yes, the ultimate authority over public universities belongs to the public. But that authority must be exercised in an ideologically neutral way. Universities are responsible for the pursuit of knowledge and education in their broadest sense, and must not be mouthpieces of state ideology. As such, they must create ample space for academic professionals working within the broad confines of their disciplines. Public universities should no more be closed to a particular ideology than should playgrounds, ballfields, libraries, or other publicly-funded spaces.

As PEN America and the American Association of Colleges and Universities wrote last June, it is vital that “colleges and universities are self-governed and self-regulated” according to principles such as “shared governance, which ensures the appropriate inclusion in institutional decision-making of members of the governing board, administration, faculty, staff, and student body.” Legislatures do play a budgetary role in shaping public colleges, but by design, they have delegated most educational decisions, including those regarding curricula, to institutions themselves. Bills such as HB 999 would change that dramatically, substituting partisan control for institutional autonomy.

The effort to pass state-level educational gag orders that target individual faculty speech is not going anywhere. But faced with skeptical courts and public opposition, lawmakers have begun to experiment with different and potentially more destructive lines of attack. The end goal remains the same: to exert ideological control over higher education and suppress academic autonomy. If successful, these efforts could do incalculable damage to the structure of American public higher education for years to come.

This update from PEN America was compiled by Jeffrey Sachs, Jeremy C. Young, and Jonathan Friedman.