Revised Florida Textbooks Left Race Out of Rosa Parks History

In an effort to pass muster in Florida, a textbook publisher omitted references to race in history texts, even when it came to Rosa Parks.

Samples provided to PEN America by the Florida Freedom to Read Project and confirmed by The New York Times showed two proposed versions of textbooks from Studies Weekly, a publisher whose curriculum is used in 45,000 schools across the country.

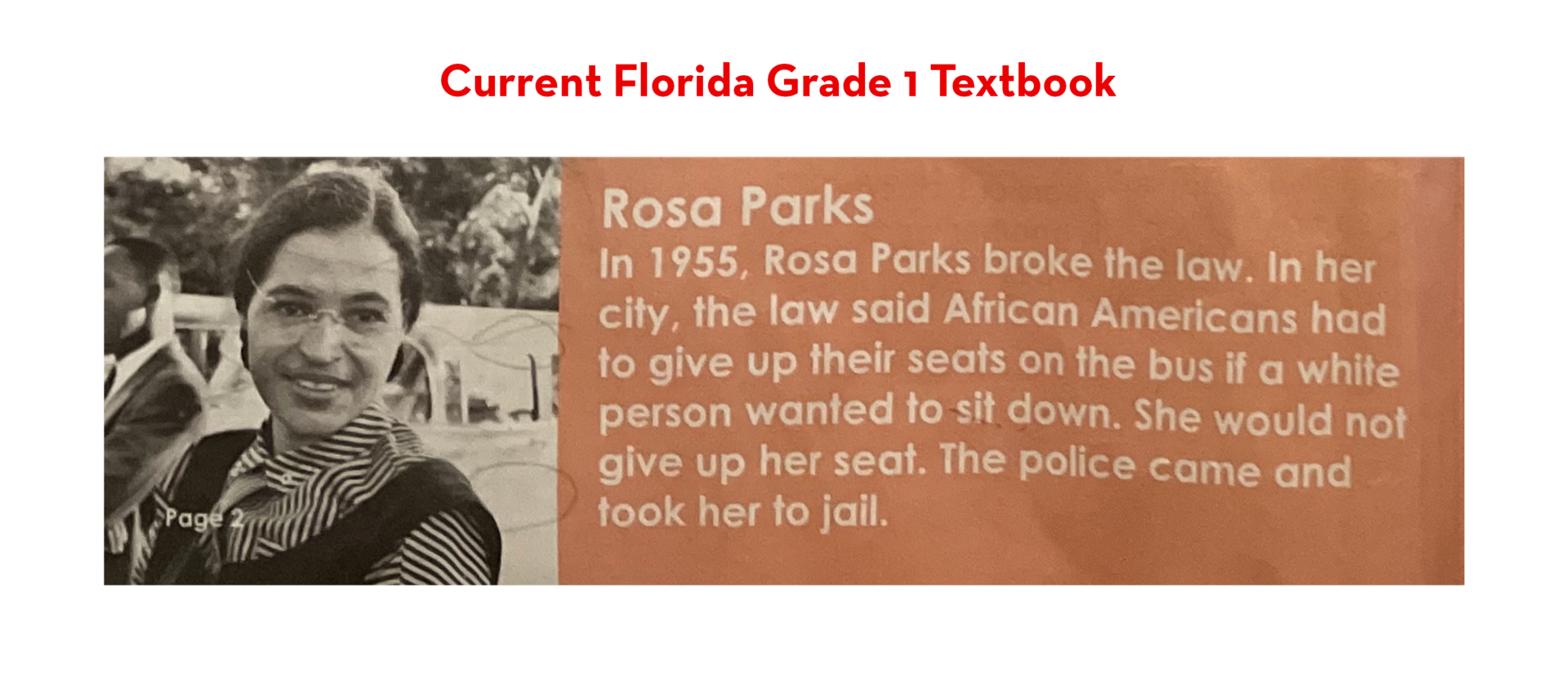

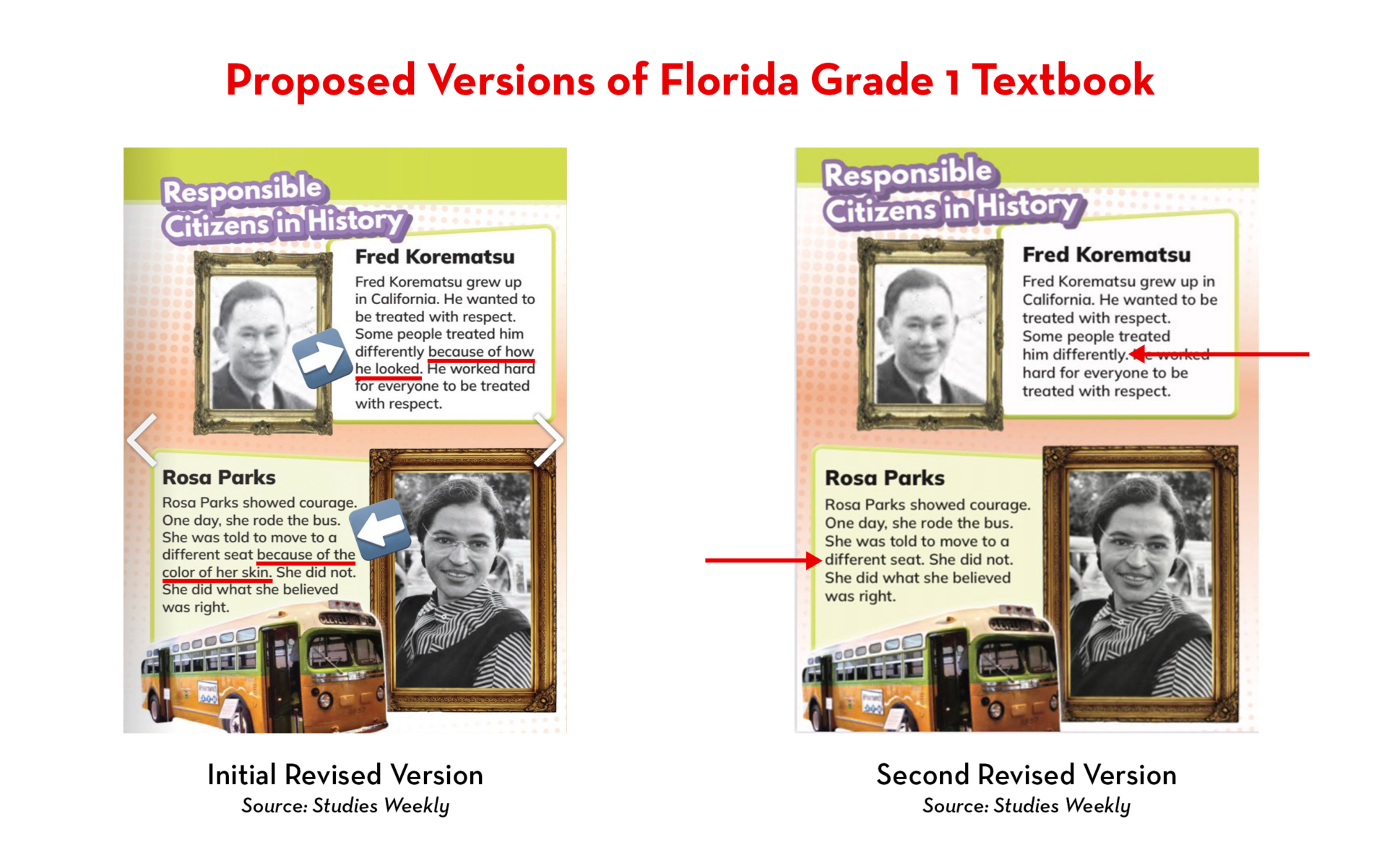

The version of the publisher’s first grade textbook currently in use speaks directly to the discriminatory law in Alabama that Rosa Parks broke in 1955. The initial revised version, however, stated only that Parks “was told to move to a different seat because of the color of her skin.” A second revised text said only that she “was told to move to a different seat.”

It is unclear which of the new versions was officially submitted to the state for review. The company told the Times it was responding to Florida’s new standards, including the so-called Stop W.O.K.E. act.

The Florida Department of Education told the Times it rejected the publisher over a bureaucratic mistake, but also said textbook changes to omit race went too far and “would not be adhering to Florida law.”

“This is how fear is destroying public education in Florida,” said Jonathan Friedman, director of Free Expression and Education Programs at PEN America. “Although Studies Weekly textbooks were rejected, and although it’s not clear which of these revised versions were officially submitted, we have to stop and recognize that even textbook publishers have grown this skittish of running afoul of Florida’s new education laws. Vague laws are causing confusion for public education — and Florida’s students will be done a disservice by such an anodyne, censored version of the history of racism in America.”

The changes reflect struggles to understand and comply with a new tangle of educational gag order laws in Florida. PEN America filed an Amicus brief supporting a challenge to Stop W.O.K.E., saying the law had a “profound chilling effect” on educators across the state. Among other things, the law prohibits educators and employers from discussing advantages or disadvantages based on race.

The initial textbook version also said Fred Korematsu, who resisted Japanese internment during World War II, was treated differently “because of how he looked.” The second revised version said only that he was treated differently.

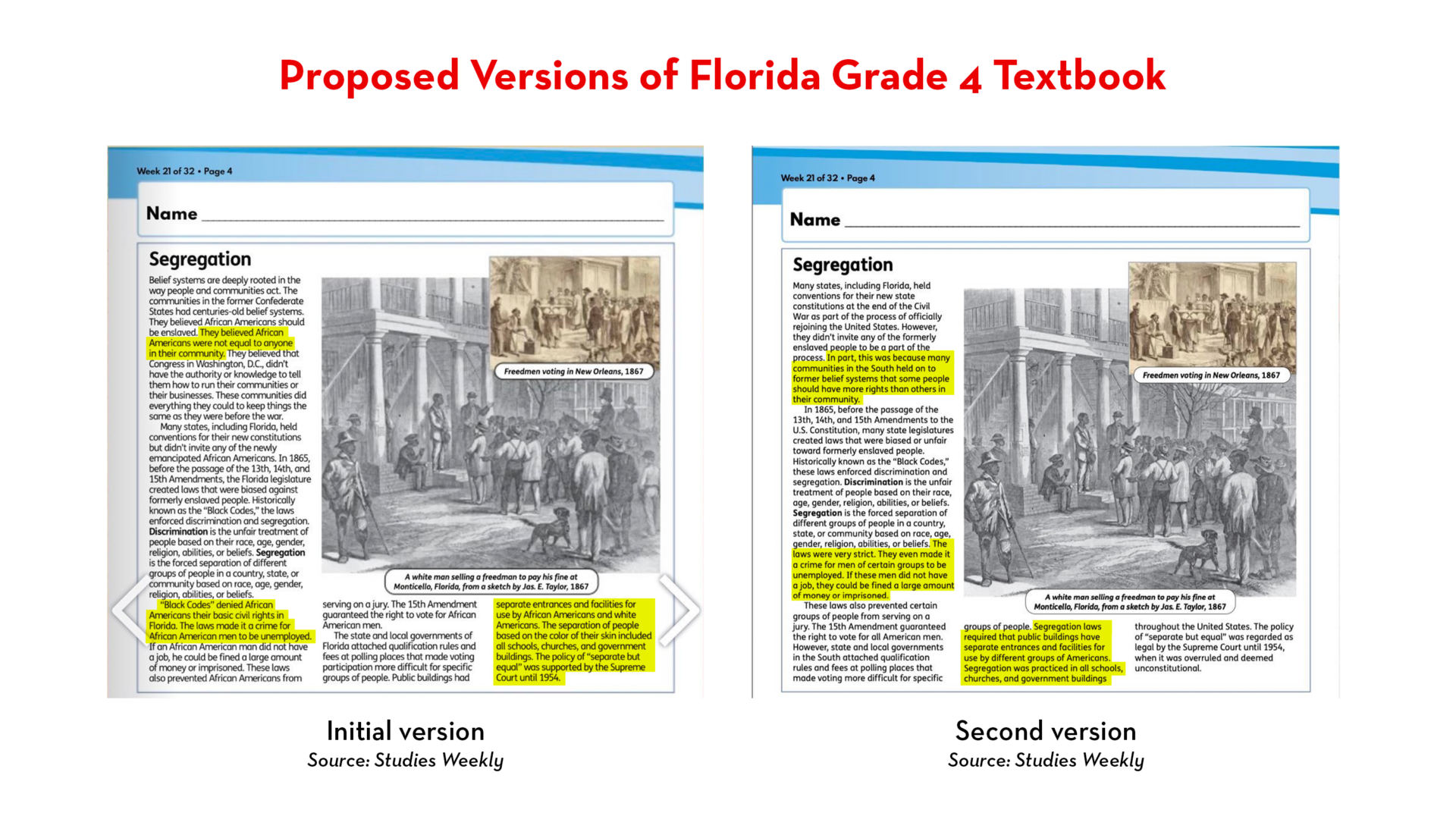

Meanwhile, the initial revision of a fourth grade textbook from Studies Weekly said that segregation initially referred to belief systems that “African American were not equal to anyone in their community.” The second revised text says “many communities in the South held on to former belief systems that some people should have more rights than others in their community.”

Although the second revised text still refers to “Black Codes,” it explains they applied to “men of certain groups.” It says segregation laws required separate entrances and facilities “for use by different groups of Americans.” The term “African American” is no longer used whatsoever.

Studies Weekly has stated that it is reverting to its first revised version of the new textbooks that include references to race, and that it may try to win over individual districts after its rejection by the state.