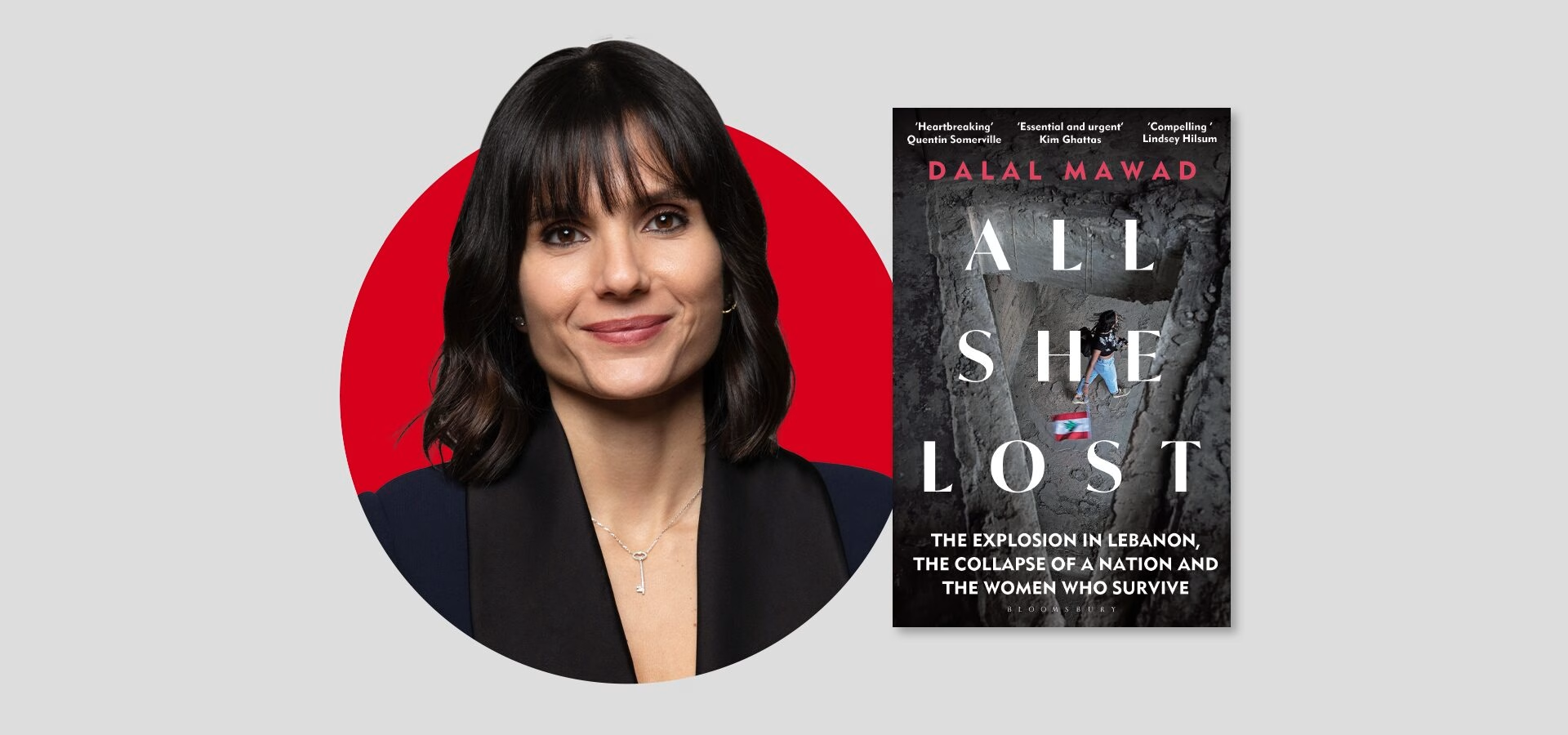

Dalal Mawad | The PEN Ten Interview

Poignant and deeply moving, Dalal Mawad’s book All She Lost is a collective memoir that captures the first-hand experiences of women who survived the devastating Beirut port explosion on August 4th, 2020. Through these stories, this book reveals the tragic impact of injustice and lack of accountability on women, hindering their ability to grieve and driving many to leave Lebanon.

In conversation with PEN America Freedom to Write Center Manager, Asma Laouira, for PEN Ten, Dalal Mawad shares personal insights into her writing process and provides an intimate glimpse into the deep and painful conversations with the women featured in the book. (Bloomsbury)

1. As an award-winning journalist and producer, what inspired you to write a book on the events of August 4, 2020 in-lieu of creating a documentary?

I wanted to go in depth into these women’s stories, I wanted them to feel comfortable to open up and share their painful history with me. A camera often intimidates and hinders that access. I also realized there was so much to cover beyond August 4, the women’s trauma transcended this event, they spoke of so many important issues. Their stories weaved together represented Lebanon’s modern history and the condition of women in it. It would have been hard to put all of that into a film. The book gave me more freedom, more space and gave them more intimacy.

2. The title of the book suggests a focus on the Beirut explosion, but as I read, I find it to be more about injustice, impunity and the collapse of a state from your perspective and that of the women you interviewed. Why did you choose to write this collective memoir from the perspective of women only?

The SHE in the title refers to more than just the women of Lebanon, in many ways it is also what Beirut has lost, what Lebanon as a nation has lost. But the focus on the women was because they rarely get to write history. Not just in Lebanon, but around the world. Women were active and prominent players in Lebanon’s history but we don’t know that because our history is never written from their perspective. A women-led narrative is crucial and much-needed. Women are survivors and victims, they bear a large brunt of Lebanon’s protracted violence and crises, but they are also changemakers, mediators, powerful actors and storytellers and so I wanted them to own their narrative.

“A women-led narrative is crucial and much-needed. Women are survivors and victims, they bear a large brunt of Lebanon’s protracted violence and crises, but they are also changemakers, mediators, powerful actors and storytellers and so I wanted them to own their narrative.“

3. These interviews are emotionally intense, with palpable trauma and tragedy in each story even for a reader. I imagine that it must have been very difficult for you to endure. How did you manage to sit through each interview, listen, and process?

The interview process was the most difficult part of the book writing. Some of these women had never spoken about what happened to them before, many were opening up for the first time. Most of them cried throughout. Their pain and their trauma were too heavy to shoulder. I often felt like a therapist, only I was not one. It was hard to stay neutral, to keep a distance. I often cried as well and stopped the interviews. I talk about how it felt to listen to them in the book. I built strong bonds with some of these women, and came back to see them every time I visited Lebanon. I felt privileged to be able to listen to them, to have their trust but I also felt very responsible to do justice to their stories.

4. You have known many of the women you interviewed, but others were strangers like Laure Al Alam. How did you build trust and create a safe space for her and others to share such profound and personal wounds?

I think building trust takes time, for many of these women, our relationship was built over time, after a few visits and chats. I did not necessarily interview them right away, and I had to show them that I cared about them beyond just sharing their stories. I was patient and understanding and most importantly worked on building a relationship of mutual respect. I was a woman, I was Lebanese and I shared many of these traumatic events with them and so I let them feel that I was there not just in my capacity as a journalist and storyteller but also as a fellow woman and Lebanese. I wanted them to feel safe and I did that by having them own their stories and narratives as much as possible . I let them guide me, tell me what they wanted to tell me. I respected their space, their pain, their need to stop talking or sharing. I tried to be a listening ear but also wanted to try and help them, support them.

5. You write in your first chapter that Laure was eager to end the interview and you felt guilty keeping her. How did you balance the need to gather crucial content for the book with the importance of not pushing too hard with potentially triggering questions?

There were only a few women, including Laure, which I did not have the opportunity to meet more than once. They were not opening up easily and were not ready. That in itself was the story and said a lot about their pain. I had to respect that and make sure I did not trigger more trauma. I did not push them beyond what they were willing and ready to give me. I still got a lot out of these meetings, I would say, but the priority was to respect their space and how far they were willing to let me in. I was trained on interviewing trauma survivors and so I crafted the questions carefully and followed the women’s lead.

“I wanted them to feel safe and I did that by having them own their stories and narratives as much as possible . I let them guide me, tell me what they wanted to tell me. I respected their space, their pain, their need to stop talking or sharing. I tried to be a listening ear but also wanted to try and help them, support them.“

6. As a trauma survivor yourself, what coping mechanisms did you use? How did you mentally prepare before each interview and how did you transition back to your normal life after hearing their painful testimonies?

This was a very personal story. It was not an assignment that I covered and then went on to live a normal life. I was, just like most of the Lebanese, affected by the explosion and the economic crisis. The period between 2019 and 2021 affected me, my family, people I loved and I personally know many of the victims of the Beirut explosion. And as much as I was trained to interview trauma survivors, I don’t think anything could have trained me for this. It was not easy. Many of them spoke for the first time about what happened to them. It was an extremely emotional journey for all of us. But I think the writing of the book itself was my coping mechanism, it was a way of processing my feelings and traumas and giving back to the victims by telling history from their perspective. I definitely carried my own wounds but it was not until later on that I took care of them. I think I always delay the processing. I speak in the book about the insomnia and anxiety that followed the research. No matter how many painful stories I had reported on in the past, these were still extremely heavy. I now think I have a better coping mechanism. I did therapy for 2 years and learnt not to delay processing. I am hoping that with time I get better at doing that.

7. You devote a section in the book to what you call “the Myth of Resilience”, likely redefining the concept for many readers. You write in that section that the Lebanese people are not resilient, they are “surviving” and “adapting” to the status quo. What is resilience to you?

Resilience should not be confused with strength, strength can be an attribute of resilience but it’s not enough. Resilience implies overcoming a misfortune, rebuilding a country around sane and healthy principles, finding solutions, adapting but to better conditions. Instead, the Lebanese are just adjusting to an impossible way of life, unable to create better alternatives. They are today an exhausted and traumatized people, conforming to a life of subsistence.

8. You mention sectarian laws and inequalities between women based on religious affiliation which are also inherently discriminatory against women. Your writing implies that this system was somehow imposed on society. Do you believe that Lebanese people, including women, and independent from government influence, would embrace a non-sectarian system?

Unfortunately sectarianism is not just institutional and political. It is also societal, educational and very much an intrinsic part of our culture. I would not say it is imposed, we accepted that system and lived with it for so long. But you have to start somewhere. And I believe that you have to change the institutional and legal framework as a first step to push long term societal change. A unified civil personal status law for example could be a beginning. There are Lebanese, including vibrant women movements, that believe in secularism today and the need to have a secular state, but they are still not a majority. Women can only aspire for equality and fair laws within a civil state. Religious courts will never give them that.

9. In your book, you describe your family’s experience of leaving Lebanon and settling in France, sharing a complex love-hate relationship with Lebanon. This sentiment is likely relatable to many immigrants who have left their beloved yet troubled homelands for a better future. Can you further elaborate on this emotional dichotomy?

A lot of immigrants and especially Lebanese would identify with this emotional dichotomy. I compare it to being in an abusive love relationship, you know your partner is hurting you but you love him and you find it hard to disconnect. It’s how I feel about Lebanon. I love it but it drains me and it has taken so much away from me and from many Lebanese. We leave looking for a better future, a better place where we can find stability, where we can thrive and be respected as human beings but once we are out, we struggle a lot to fit, to feel at home. I think this extract from the book illustrates how I feel “Lebanon is pain, a lot of it, but it is also life and love. It is the backbone of my childhood memories, the bits and pieces of a broken relationship from which I will probably never recover. It is not easy feeling constantly torn between two places, and not feeling whole in either. Maybe my identity is just that, it is not de ned by one place, it is not static or complete yet. I am still forging it. “

“I don’t expect our politicians to give us our rights. Our rights will never be given, we have to take them. And so today, more than ever, grassroot social movements, which have been crucial in the fight for equality, need to make sure that women’s rights are not sidelined because there is an economic crisis and a life of survival. Women rights should not be separated from the greater fight for human and civil rights.“

10. You write extensively about gender apartheid in Lebanon and discriminatory sectarian laws, and their paralyzing impact on women. Since the devastating losses of the explosion, have you seen women effectively reclaiming social and political spaces? And have there been significant pushbacks?

Despite the unprecedented economic crisis the past 5 years, there are still women fighting and trying to reclaim their social and political space in Lebanon and they give me hope. But I am afraid women’s rights are not on the top or even part of the patriarchal political establishment’s agenda. The few women in parliament and their allies are always facing a pushback. I don’t expect our politicians to give us our rights. Our rights will never be given, we have to take them. And so today, more than ever, grassroot social movements, which have been crucial in the fight for equality, need to make sure that women’s rights are not sidelined because there is an economic crisis and a life of survival. Women rights should not be separated from the greater fight for human and civil rights.

Dalal Mawad is an independent award-winning Lebanese journalist based in Paris, France. She is working as freelance producer for CNN in Paris and as a part-time journalism professor at Sciences Po. Mawad was a senior producer with the Associated Press based in Lebanon when twin blasts rocked Beirut on August 4th 2020. She extensively covered the explosion and its aftermath as well as Lebanon’s economic and financial crisis since 2019. Her AP bylines have been published in the Washington Post and New York Times. Mawad is the winner of the Samir Kassir Award for the Freedom of the Press in 2020 for her short film on a transgender woman in Lebanon, and was a finalist in 2012 for an investigative story on Lebanon’s Jews. Mawad has also worked as a regional video producer for the United Nations Refugee Agency covering displacement in the Middle East and the world. Previous to her work at the UN, she was an on-air reporter with LBCI, a Lebanese broadcaster, where she mainly covered human rights and gender-based violence. She has a Master’s degree in International Political Economy from the London School of Economics and another Master’s degree in Journalism from Columbia University in New York where she was awarded the Joan Konner award for outstanding reporting for Television and Radio. She is fluent in Arabic, French, English and Spanish.

Marcela Fuentes | The PEN Ten Interview

For Pilar, her anxieties and insecurities solidify into this belief that she has been cursed. She accepts it as true, and it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts.

Matthew Mendoza | The PEN Ten Interview

Place and story are important to me. The best work exists where the amazing and magical meet the sinister.

Parul Kapur | The PEN Ten Interview

There is always a cost to defiance. The question is whether you can bear it or how you can transcend it.

Lisa Grunwald | The PEN Ten Interview

I was looking for a time in American life when things seemed as passionately divided as they do now.