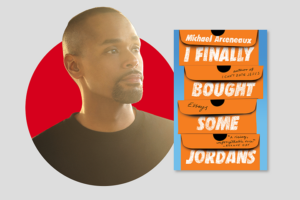

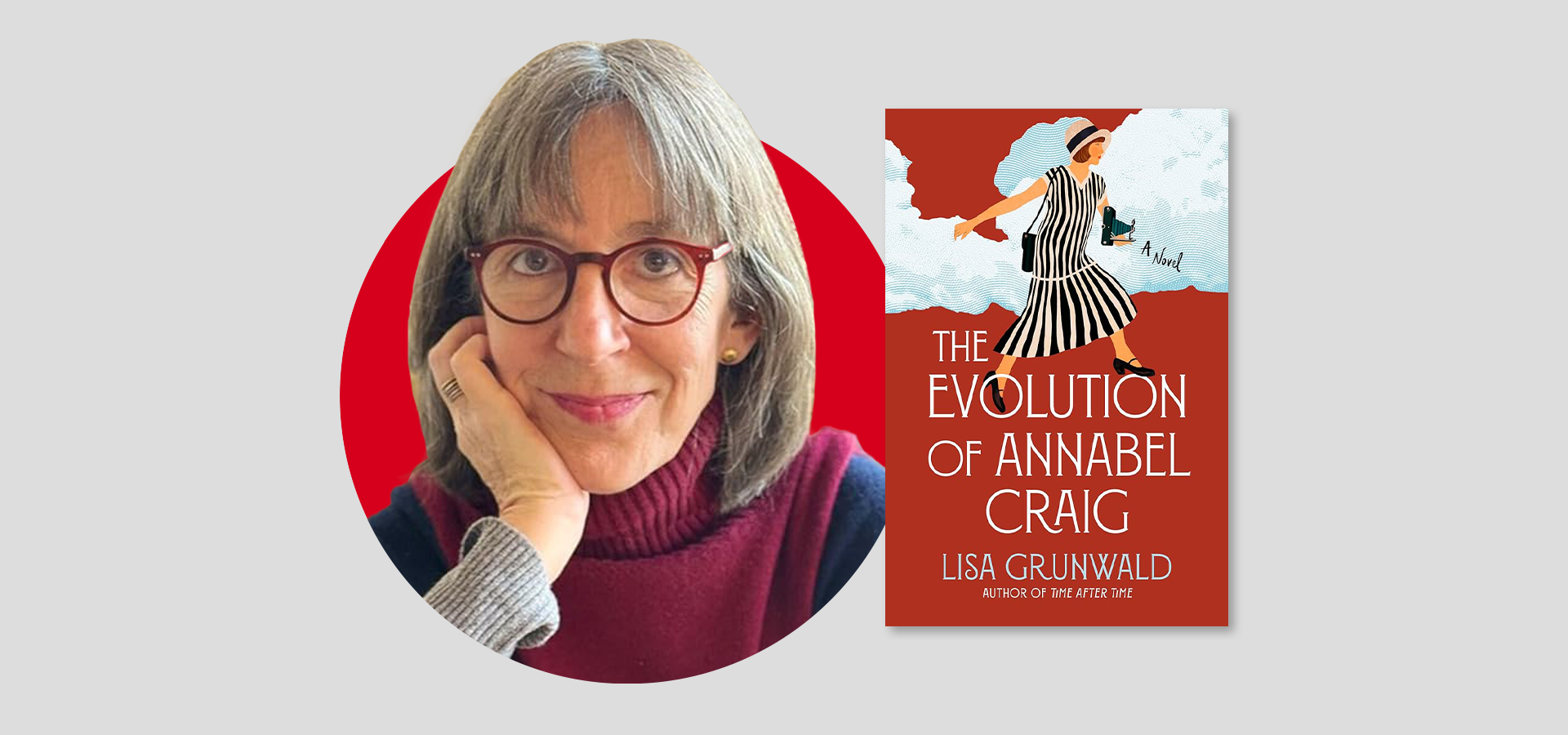

Lisa Grunwald | The PEN Ten Interview

April 16, 2024

In exploring the 1925 Scopes trial from “the other side” for her new novel, The Evolution of Annabel Craig, Lisa Grunwald was forced to grapple with her own assumptions. The novel – Grunwald’s seventh – tells the story of a young woman coming of age in Dayton, Tennessee, juxtaposed with the real events of the “monkey trial,” in which former presidential candidate and religious fundamentalist William Jennings Bryan battled fabled defense attorney and agnostic Clarence Darrow over a law banning the teaching of evolution in public schools.

In an interview with Jeremy C. Young, PEN America’s Freedom to Learn program director, Grunwald discusses the value of looking at a major historical event through the lens of one woman’s experiences, and the importance of challenging one’s beliefs and keeping an open mind. (Bookshop)

1. The Scopes Trial happened nearly 100 years ago. What motivated you to retell the story now?

Because of Donald Trump – or at least the divisions in the country that Trump unearthed, and to some extent inspired. Four years ago, I was struck by the fact that people I knew, families I knew, were divided by this phenomenon to the point where at family gatherings, suddenly politics was a forbidden topic because it was so emotional and so divisive. I wanted to write about that, but I didn’t want to write about today. I’ve written historical fiction before, and I was looking for a time in American life when things seemed as passionately divided as they do now. I thought about the Civil War, obviously, and I thought about Vietnam. But then I thought back to this, and it was just an irresistible impulse to dive into that moment.

My understanding of the Scopes trial was shaped to a large extent by this play, later movie, Inherit the Wind. I thought it was very black and white – the good guys versus the bad guys, the educated versus the uneducated, the religious versus the scientific. As I got into it further and further, I understood that there were subtleties, and that William Jennings Bryan was not Donald Trump, and vice versa. But that was the inspiration.

2. As you note in your previous answer, there are two famous retellings of the Scopes Trial that dominate most people’s understanding of what happened: the 1960 film Inherit the Wind, directed by Stanley Kramer from the play of the same name, and Edward J. Larson’s 1997 historical account Summer for the Gods, which won the Pulitzer Prize. How do you situate The Evolution of Annabel Craig in comparison to those works?

I think Ed Larson’s book is marvelous in correcting the record, as far as I understand it. I’m not a historian, so I can’t judge the specifics of how accurate or inaccurate that amazing book is. I certainly can, though, look at Inherit the Wind and realize that the demonization of Bryan, the demonization of the faithful, the religious, and the fundamentalists, was absurd and absurdly exaggerated. Not just for Dayton, Tennessee, at that moment, but also for fundamentalism in general.

The trial was certainly dramatic; I’ve read the transcript a thousand times. But when Clarence Darrow said, “How do you explain? Don’t you realize that the Earth would have shriveled if the sun had stood still? Do you really mean that Jonah stayed alive inside of a whale” – or, as Bryan corrected him, “a big fish?” I initially thought Darrow had scored a point; hooray for the intellectual team. But reading Bryan’s answer, which is, “One miracle is as easy for me to believe as another” – it suddenly made sense to me that if you believe in a supernatural being, of course you believe that it can control nature in any way it wants.

So my book sits somewhere in between these two milestones, and it is somewhat sympathetic, or at least attempts to be sympathetic, to what I always thought of as the other side.

“I was looking for a time in American life when things seemed as passionately divided as they do now.“

3. One of the freshest aspects of Evolution is that in a historical event often dominated by larger-than-life men, you’ve chosen to focus on the coming-of-age story of a female protagonist. The first quarter of the book describes Annabel’s life before the trial even begins, and throughout the book you bring the reader back over and over to her home life, her marriage, her friends and neighbors. What does the focus on Annabel bring to the story?

The trial took place at a time when women had just gotten the vote, when women were – especially in the North, but in the South as well – just beginning to understand the power that they had. I wanted to look at a family, and how it was affected by this moment, and because I wanted to look at how great political struggles can affect a family, I wanted a woman. The men, both in the history and also in the novel, are fabulously famous for their posturing and their eloquence and their passions. I wanted to see how not just one woman, but three women – Mercy, Lottie, and Annabel – dealt with the intensity of those men. And I liked the idea that, in being witness to this trial, Annabel wouldn’t pick a side. She would simply start to ask questions, which was something that was new to her. I wanted a woman who had never been exposed to these ideas to be exposed to them. It was easier with a woman, and also I wanted her to have a moment of independence and freedom, which I think she achieves by the end of the book – but we’ll see!

4. Another surprising part of the book is that Annabel is a person of faith. The story of the Scopes Trial is often told as a triumph of eloquent atheism and science over what Clarence Darrow called “your fool religion.” Why did you make that choice?

I thought that the other version had been told so many times. When I first started thinking about the book, I thought, okay, I’ll have a woman who’s married to an atheist. And she’ll be a woman of faith, and he’ll convert her, basically. The more I read – and not just about the time, but also about the town, about the trial, about fundamentalism, about Bryan College, about how these events are viewed from what I think of as the other side – the more I wanted to try to understand what a woman of faith would feel.

I had the good fortune of knowing a woman about 10 years younger than I am, who had lived in New York for a brief while while trying to be an opera singer, and who is deeply faithful. She got married at the age of 40, and moved back to North Carolina. I got her on the phone – I hadn’t talked to her in years – and I just said, “Could you please explain what this is all about, how it feels, what you really think? What does evolution mean to you? What did you think about it growing up? Would you allow me to ask you questions?” We had amazing conversations. She was generous with her time, but patient with me, because she was trying to explain a different language, and I was trying to learn a different language.

I’m not sure I’ll ever entirely understand the necessity of ruling out or keeping out science. But it would have been too predictable and too easy for me to have a character who was all sciencey, or all faithful. I wanted somebody whom I didn’t understand in the first place, and whom I came to understand as I learned more.

“I wanted to look at a family, and how it was affected by this moment, and because I wanted to look at how great political struggles can affect a family, I wanted a woman.“

5. The story of the Scopes Trial is usually focused on oratory, particularly the competition between Darrow’s debate-driven style of courtroom examination and William Jennings Bryan’s ponderous elocutionary style. While Evolution does not ignore these aspects of the trial, Annabel and her friend Lottie engage instead in photography and journalism. How does shifting focus to these forms reshape the narrative?

Bryan and Darrow, and H.L. Mencken, too, were on a stage. I don’t think Lottie and Annabel saw themselves that way, even though they were creating something that was part of a record; they were responding to the moment. Darrow and Bryan were trying much harder and shooting much higher for a lasting effect. Lottie is based on a real reporter named Nellie Kenyon, who was the first person to get a press pass to the trial. She knew, apparently, before anyone else did, the second that the ACLU issued its challenge, that this was going to be big. She had a sense of the history of it, and I think Lottie does, too. But I think Bryan and Darrow were both aiming for the fences. They were really trying to create the definitive argument between the two sides. The other thing that I discovered is that Darrow had already asked Bryan these questions in another venue. In Inherit the Wind, it seemed as if he was just thinking of them, as Spencer Tracy was doing his thing. But Darrow had already said. “Did Jonah really live inside a whale? Where did Cain get his wife?” and so forth. So it’s a difference in scale.

6. One of the most impressive aspects of the book, to me, is how you construct a language of the rural South that draws on the vernacular of the time and place in a way that is endearing rather than precious or patronizing. In places, particularly when Annabel is describing her childhood with her parents, the style reminds me a bit of James Agee. How did you accomplish that?

I wanted there to be some level of credibility that this wasn’t just being written by a 64-year-old New York Jewish woman. Credibility is essential when you’re writing historical fiction, or really when you’re writing anything. How I did it was largely by keeping myself from trying too hard. I have a friend, a novelist named Betsy Carter, who also has written historical fiction, and we read each other’s work all the time. We tell each other, “your facts are showing.” That is a great temptation.

Google Southern vernacular of the early twentieth century, and you come up with fabulous expressions that, if they showed up in the book, you would say, no one talks like that. So I tried to go as gently as I could. I tried to make sure that Annabel, in narrating, wasn’t using any words that she wouldn’t have known – that’s really important – and that she not describe things with metaphors or references to things she wouldn’t have known about. There’s a lot of fact checking involved in this. You want to say “as fast as a plane,” and you realize she’s never seen a plane.

That’s part of it – the language. The other part was, again, my friend Debbie from North Carolina, and her sister, whom I also know. I sent them both a very early version of the manuscript. I had something about black-eyed Susans in the field, and they said, “You’d never call them black-eyed Susans; it’s always black-Eyed Susies.” So there were little things like that where I got corrected along the way. “I wouldn’t have said Father, I would have said Papa.” That kind of thing. So my best efforts not to sound like a New Yorker trying to sound like a Southerner, let alone a faithful Southerner, in 1925.

7. I think it’s fair to describe Evolution as a feminist novel, although I’m interested in your thoughts on that question as well; Evolution has a close kinship with Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, which is referenced multiple times in the book. But Annabel’s feminism, in the end, isn’t really of the same flavor as Edna’s in Awakening. Can you talk about the connection and how you situate the novel among those questions?

I don’t know if it’s a feminist novel, but it’s certainly a novel about a woman’s independence and her sense of herself. When I was first describing this book to my editor, Kara Cesare, at Random House and her boss, Susan Kamil – who unfortunately died very young and very fairly recently – Susan was on the telephone. This was pre-pandemic, and so it was pre-Zoom, but she had called in from wherever she was, and I was rattling on about what I thought the book would be. And there’s this pause, and she said, “Oh, so it’s The Awakening, but set during the Scopes trial.” I said, “Yeah, I guess it is.”

I immediately reread The Awakening. At the end of The Awakening, the main character’s expression of independence is to die – to kill herself because there’s no other way for her to be free of marriage, of expectations, of the society in which she’s lived. I thought that was a little dark, and I did not want to do that. But there’s definitely this sense that her discovery – and I think this is true of a lot of women then, and now, too – that you get to a moment where you can look at your life and say, this actually isn’t what I had in mind, or this isn’t actually what I deserve; I’m entitled to something more.

The largest debate that I had with my friend Debbie was that she said Annabel would never leave her husband. I said, “Would she have to? What would your husband have to do in order for you to leave?” Because along the way to leaving there would be a lot of prayer and a lot of compassion, and a lot of just hoping that he finds his way back. But in that sense I gave Annabel more freedom and decided that she simply needed to get out of this, that she was young enough and curious enough that she could get out of the situation she was in, both with her husband and with her town. I think that’s a much more hopeful feminism than swimming out too far in the water until you drown.

8. Another subtext in Evolution, seen only through brief glimpses, is racial segregation in the Jim Crow South. Annabel’s world is populated largely by white actors, though she mentions briefly her revulsion at racism and lynching. How does the Jim Crow context inform your narrative?

I felt I needed to be very careful and delicate around that question. The Ku Klux Klan was incredibly big in Tennessee, particularly at that time. And it is true, as I say in the book, that most of the waiters at the Aqua Hotel in Dayton were Black and some of them might well have been aware of the antagonism, not to say racial hatred, that was aimed at them while they were serving meals.

I was also very much aware that the dark side of Darwinism is eugenics, and I wanted Annabel to be repelled by that idea. I’m not sure, realistically, she would have gotten far enough in her thinking, after just a little bit of exposure to the implications of that, that she would have been as appalled as we are.

One aspect of the trial that I didn’t get into: there were present at the trial in Dayton a number of Black preachers – one in particular from the North who had come to support John Scopes, oddly, because Darwinian logic said that there were different races, and that whites were more advanced. Yet the argument from this preacher was that if you improve education in general, eventually you’re going to improve education for Black people as well. In the Black press – I read a lot of it – there were cartoons, one of which is memorable to me. There are a bunch of monkeys sitting in trees, looking down at the town, and a very small depiction in the distance of a lynching. The caption is something like: “And they say we’re less evolved.” That view that showed up in Black newspapers; not at all that I could see in the mainstream media.

“The bigger take away that I would want a reader to have is: What are the questions you haven’t asked? Ask them. If you think you know the answer, make sure that you really do.“

9. I’m interested in your use of foreshadowing in Evolution. Annabel refers multiple times throughout the book to her life after the Scopes Trial, but ultimately the reader only sees glimpses of that life. Why did you make that choice?

There was a time that I set the novel in the future and had her looking back. But it required a very specific set of decisions about where she ended up and what she ended up believing. I didn’t want her to look back and say, when I was a religious person I thought this. I imagine her bicycling around a college campus somewhere, or working as a photojournalist. But I didn’t actually want to complete that narrative. I wanted to nod to the future, to a future in which she was more enlightened, more informed. But I didn’t really want to pin it down, because I didn’t want to pin her down.

10. What message do you want readers to come away with? In an age of censorship, misinformation, disinformation, and other threats to knowledge and literature, what is the message of The Evolution of Annabel Craig for our time?

The specific message is that the classroom should be a place where ideas of all sorts are present, and are open for interpretation, but that it should not be a place where any religion is considered something that must be taught. It’s absolutely clear to me that the First Amendment says you can’t do this – you can’t put Christianity in a classroom. That’s a specific message, and it’s about the classroom and about Scopes’s apparently absolutely sincere desire to say, this is a bad law.

The bigger take away that I would want a reader to have is: What are the questions you haven’t asked? Ask them. If you think you know the answer, make sure that you really do. And push yourself to look across the aisle, if it’s politics or the pulpit, if it’s religion or the classroom, and expose yourself to that about which you have assumptions, but about which you may not be right. It’s really about tolerating the discomfort of asking a difficult question.

Lisa Grunwald is the author of the novels The Evolution of Annabel Craig, Time After Time, The Irresistible Henry House, Whatever Makes You Happy, New Year’s Eve, The Theory of Everything, and Summer. Along with her husband, former Reuters Editor-in-Chief Stephen J. Adler, she edited the anthologies The Marriage Book, Women’s Letters, and Letters of the Century. Grunwald is an occasional essayist and runs a side hustle called ProcrastinationArts, where she sells the other things she makes with pencils and paper. She lives in New York City.

The PEN Ten Interview Series

Deborah Jackson Taffa | The PEN Ten Interview

Kevin Huizenga | The PEN Ten Interview

Remica Bingham-Risher | The PEN Ten Interview