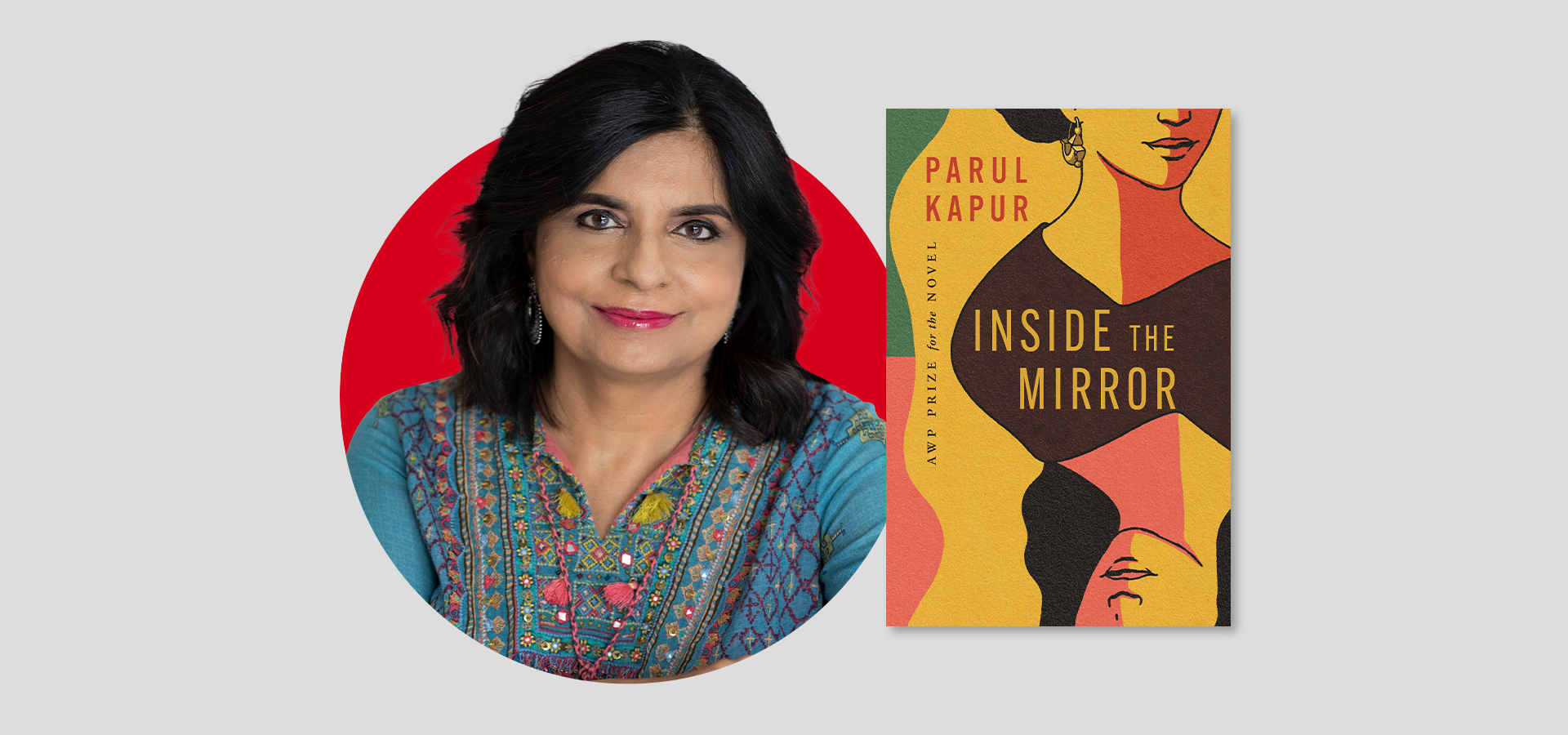

Parul Kapur | The PEN Ten Interview

May 6, 2024

Parul Kapur’s debut novel, Inside The Mirror (University of Nebraska Press, 2024), tells the story of twin sisters Jaya and Kamlesh in 1950s Bombay. It explores the modern art movement in a newly independent India, the complex family ties which support but also bind, and women’s creativity and agency. As both women struggle to pursue their passions despite their father’s wishes, their connection to each other is strained as their family’s standing and reputation are threatened.

In conversation with Free Expression Leadership Fellow Manasi Garg, Parul Kapur discusses the relationship between art and politics, going against patriarchal expectations, and the literature that has mobilized her work. (Barnes & Noble, Bookshop)

1. In the novel, Jaya and Kamlesh begin discovering the limits of a “respectable” woman’s place, both in their community and in Indian society at large. The sisters come from a progressive family – their father pushes them to become highly educated, and their Bebeji, their grandmother, was a freedom fighter. Despite this, Jaya and Kamlesh still knock against many gender-based restrictions. How have you, or others you know, navigated the idea of “a woman’s place” in your/their own life?

I came of age in the 1980s, when women were charging into corporate offices in their power suits. My mother, who’d had a traditional upbringing in India, though she was college educated, became a Montessori teacher in America. Later, she went into real estate and built beautiful spec homes during the Reagen boom years. Even today, you don’t hear of women general contractors, so an Indian woman in that role back then was astonishing. “A woman’s place,” as far as I was concerned, was out in the world. After I earned my MFA at Columbia, I went to work for a travel magazine. I found myself stuck in a cubicle all week with no daylight. My mornings began with a tortured subway ride. Suddenly I felt trapped. I lacked the time and mental space to write fiction. I turned to working as a press officer at the United Nations on short-term contracts, so I’d have the freedom to write in the mandatory weeks off.

Then I got married and moved to Germany. My duties became a traditional German housewife’s duties—though I drew the line at polishing my husband’s shoes! Our son was born after we returned to the States, and more of my time went into my family and home. I both thoroughly enjoyed and resented this at different times. I was a freelance writer, lacking the status and income of working for a prestigious employer. Yet I had the privilege of being supported by my husband and having time to write fiction. That’s why many people now want to work from home—time and freedom. ‘A woman’s place’ inside the home can be a liberating thing, if she can redefine it to suit her purposes.

2. Inside The Mirror follows many threads to create a rich tapestry of 1950s Bombay – Bebeji’s past as a freedom fighter and reinvigorating work for the people of the hill colony, Jaya’s journey as an artist and her first romance, Kamlesh’s relationship with Bharat Natyam. As with any story, there were likely an infinite number of other plotlines you could have pursued. How did you craft this story?

During my MFA, when I began writing Inside the Mirror, I was reading epics like Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and Joyce’s Ulysses, so the novel grew to encyclopedic proportions in my mind. Initially, it was going to cover several generations of the Malhotra family, from the 1950s to the 1980s. For a long time, the twins’ grandmother was a major character with a controlling point of view. I was afraid a story centered on two young women would be slight, lacking the weight of history Bebeji embodied. Yet I didn’t have the skills to execute the grand narrative of my ideals. As time went on, I found I was most interested in the twins’ journey to find their way as women and artists, and that I really wanted to write a kind of A Portrait of the Artists as Young Women.

The twins’ quest to become artists was like my quest to become an artist—a novelist. The urgency of their desires, their doubts—all of that was mine. I wanted them to succeed, so I placed fewer obstacles in their way at first. I had a superstitious belief that if they succeeded, then I would succeed. But you can’t write a novel as a foretelling of your destiny. So life got tough for them. Society became very punishing, as it would have been at that time toward girls trying to carve their own way in the world. Their fates became theirs, not mine.

“I had the privilege of being supported by my husband and having time to write fiction. That’s why many people now want to work from home—time and freedom. ‘A woman’s place’ inside the home can be a liberating thing, if she can redefine it to suit her purposes.“

3. What is your relationship to place and story? Are there specific places you keep going back to in your writing?

I began writing short stories as an undergraduate at Wesleyan University. Every story was set in India, although I had not lived there since I was seven years old. It was an unconscious pull. It’s as if my mind and heart had been left behind. That’s why I considered a reverse migration and went back to India after college, working as a reporter in Bombay (now known as Mumbai). But I missed my family and returned to the States. In addition to Inside the Mirror, I’ve drafted a novel of immigration that plays out in India but ends in America. A third novel-in-progress is set mostly in America, my mind and heart slowly making their way here.

4. In the book, you write; “A girl pulling herself out of the web of her family could cause the entire web to tear and collapse.” Have you ever gone against your family’s expectations? What was the result of that?

My parents expected me to get a well-paid job at a good company, the dream of many Indian immigrants for their children. At the time, their expectation felt like an obstacle. My mother insisted I go to graduate school for an MBA—an MFA in fiction writing made no sense to her. Since she wouldn’t pay for the degree, I was lucky to get a scholarship and a loan from a relative. One of the reasons my parents had left India was to find financial security here. I didn’t understand their fears—I simply wanted the freedom to write and be who I wanted to be.

Yet I tried in my own way to appease them. I interviewed with investment banks as I was about to graduate from the writing program at Columbia. At Lehman Brothers, I was asked what I hoped to accomplish in the next ten years. I said I hoped to have published three books. That might have been one reason why I didn’t get the job. It’s hard to defy your parents when you’re young. I was always torn between being good and being my strong-willed self, appeasing and defying my family in turn.

“I think it’s only now being understood in the West that modernism became a global language adopted by decolonizing nations. Jaya, the heroine of my story, is drawn to the bold expression of modernist painting. When her teacher tells her that the Prime Minister said, “Modern art is part of making India modern”—an actual quote from Nehru—she has a sense of becoming part of India’s future, leaving the misery of the colonial past behind.“

5. I loved how beautifully Inside The Mirror contemplates the role of art in the formation of India’s identity, just a few years after Partition. How does art inform politics and culture, and vice versa?

In the 1950s, India was just beginning to rise after two centuries of cultural degradation and impoverishment under British rule. For their final act, the British partitioned India, resulting in enormous bloodshed, with several million people killed and over twenty million displaced. The nation looked to Prime Minister Nehru to guide it out of this darkness, and Nehru offered a vision of India made anew with modern industries, power plants, and housing for refugees. And he wanted to build India up in style, hiring Le Corbusier to design the capital of the partitioned state of Punjab. Indian artists embraced modernism as part of this rebirth. They had not seen the great works of European painters in person but, like Nehru, they were visionaries, and willed themselves into being. I think it’s only now being understood in the West that modernism became a global language adopted by decolonizing nations. Jaya, the heroine of my story, is drawn to the bold expression of modernist painting. When her teacher tells her that the Prime Minister said, “Modern art is part of making India modern”—an actual quote from Nehru—she has a sense of becoming part of India’s future, leaving the misery of the colonial past behind.

6. In the book, artist collectives like Group 47 are inspired by traditions of Indian art across the subcontinent, and emphasize breaking away from European rules. Jaya sees art in her life every day, and learns from other Indian artists, like the fictional Sringara and the real Amrita Sher-Gill. As a writer, which literary traditions and texts do you draw inspiration from? How have they shaped your work?

I like long, intricate novels that pull me into a culture as much as into individual characters and sensibilities. I have friends who can devour a book in a day or a week; I might spend three months absorbed in an epic like Palace Walk by Naguib Mahfouz, which sucked me into the life of a family in the rigid patriarchy of early 20th-century Cairo, or Shuggie Bain, by Douglas Stuart, which is a gritty and moving autobiographical novel about a boy growing up with a vain, alcoholic mother in Glasgow. Another mesmerizing epic is Yashpal’s This Is Not That Dawn, about the shattering of Punjabi lives by the British Partition of India. The scenes of dreadful violence are masterpieces of drama and description by a writer who was both a journalist and a revolutionary. All of these works are deeply rooted in their societies. Perhaps they’ve helped me render place with a specificity and sense of history in my own fiction.

Amrita Sher-Gil’s painting Three Girls was a touchstone as I revised Inside the Mirror for publication. Sher-Gil was the Frida Kahlo of India, a flamboyant personality and artistic genius brought up in Europe and educated at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. She returned to India, deciding her artistic destiny lay there. Three Girls stands out among her many portraits of Indians for the tender depiction of melancholy and submission she saw in Indian women. I also see in the downcast faces the sorrow of a people living under colonial oppression. Since my protagonist, Jaya, paints Indian women as well, I kept going back to Three Girls to decide what were other qualities, particularly strengths, that Jaya saw in the women of her world.

7. In the Acknowledgements section, you write that this book and its inception began decades ago. What sparked the idea for Inside The Mirror, and how did you nurture that spark?

The year I spent as a journalist in Bombay after college was life-changing. I returned to America with a deeper sense of my Indian identity, and the novel grew out this overwhelming experience. Two stories I wrote for the city magazine where I worked particularly touched me—one on a colony of dancing girls and another on a neglected slum. Both the figure of the dancer and the slum appear in different forms in my novel. What kept me inspired during the twenty-five years it took to compose the novel was interviewing people. Because the Indian diaspora is vast, I was able to find doctors who’d trained at the medical college where Jaya is a student, artists who’d been part of the modern art movement I fictionalize, and many others who could speak to me about aspects of the novel. I also made several trips backs to India. Every conversation offered a jolt of energy and nuggets of information I was excited to include in my story.

8. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I had a lovely teacher in third grade who used to read us a few pages of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory at the end of every school day. It was the most delicious treat. I can still feel the thrill I felt the moment Charlie found the golden ticket. I remember the absurdity of the four grandparents sharing the same bed. Chewing gum that tasted like a full-course meal. Every scene felt like a bit of magic spun from words. Perhaps this first story I heard upon arriving in America awakened me to the remarkable powers of language.

“Because the Indian diaspora is vast, I was able to find doctors who’d trained at the medical college where Jaya is a student, artists who’d been part of the modern art movement I fictionalize, and many others who could speak to me about aspects of the novel. I also made several trips backs to India. Every conversation offered a jolt of energy and nuggets of information I was excited to include in my story.“

9. What was one of the most surprising things you learned in writing your book?

I discovered I had the ability to give up. That can be a good thing, because it frees you. For twenty-five years, I worked doggedly on this novel. I was far from India, I had never experienced the 1950s, yet because I’m a journalist, I was driven to make the story as accurate as possible. This slowed me down considerably. Finally, I revised the novel to my satisfaction, but I couldn’t find an agent because it was too long at 600 pages. It felt like a great disloyalty to put the manuscript away. I had been devoted to my characters for most of my adult life. And yet, as I sealed the pages up in a box, I felt it contained a great energy, a whole world, and I had a spurt of confidence that the book was alive and might one day make it into the world.

10. The book centers on two women struggling to create their own identity and lives. What advice do you have for women trying to define themselves outside of cultural expectations?

Follow your desires if they are deep and essential to the fabric of your being. But realize there is always a cost to defiance. The question is whether you can bear it or how you can transcend it.

Parul Kapur was born in Assam, India and raised in the United States. Her fiction appears in Ploughshares, Pleiades, Prime Number, and more. She has contributed articles and reviews to The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal Europe, Esquire, Art in America, Slate, Guernica, Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Paris Review. She was a press officer at the United Nations in New York, and worked as a reporter at the city magazine Bombay in India. She holds an MFA from Columbia University and lives in Atlanta. Learn more at https://www.parulkapur.com/

The PEN Ten Interview Series

Lisa Grunwald | The PEN Ten Interview

Deborah Jackson Taffa | The PEN Ten Interview

Kevin Huizenga | The PEN Ten Interview