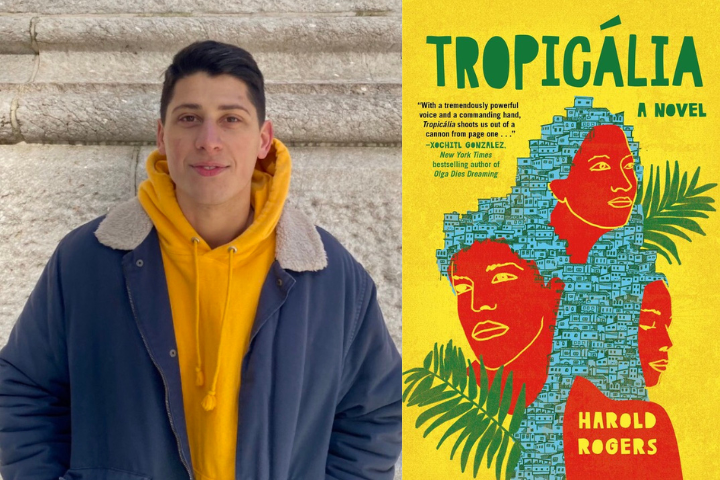

Harold Rogers | The PEN Ten Interview

In conversation with PEN America’s Program Director, Literary Awards, Donica Bettanin, Harold Rogers speaks about moving between different voices, cultures and artforms, and how these things shaped the vital and vivid novel that signifies his literary debut.

In the heady days before a New Year’s Eve party on the bustling sands of Copacabana Beach, a family reckons with a matriarch’s long-awaited return. As Daniel Cunha grapples with being dumped by his pregnant girlfriend, the death of his grandfather, and the unwanted reappearance of his mother with her American husband in tow, family secrets are shaken loose and resettle around him, revealing generations-old fault lines–and new ways of relating.

1. Tropicália is told by an ensemble of voices spanning several generations of one family, to indelible effect! What led to this artistic choice? Did the manuscript always contain these multiple perspectives?

For a while I was dabbling with a few short stories written in the third person about two characters who were siblings: Daniel and his younger sister Lucia. I decided what I was working on was probably a novel and that’s when I changed from writing in third person to first person and the voices really started to gain energy. The breakthrough though was Grandma Marta’s chapter. That’s when I decided to try to write from the perspective of all the immediate family members (without that constraint it would’ve gotten pretty unwieldy). What I love about the multiple first person perspectives is that it allows me to discover how these characters conceive of themselves in their own language and syntax and as a Self navigating the pesky entanglements of time and other Selves—and it granted me a lot of freedom to play around with tone and language and story.

2. Reflecting on moving from reading in English to reading in Portuguese, Lucia asks, “What was the point of integrity with a language? Integrity with an identity?” Are these questions you have grappled with as a writer?

Definitely. This is a story about Brazil written in English. The only reason for that choice really is that I can write in English much better than in Portuguese. I’m fortunate in that because Portuguese is a minor, peripheral language in the world sphere of literature. This book will receive much more attention just by the simple fact that it was originally written in English. Though I like to think of this book in my own conception as if it was written by Lucia in Portuguese and translated by me… I feel like an identity brings about certain duties though especially as a writer: I feel a duty to balance my reading between English and Portuguese; and I feel a duty to engage with Portuguese as much as possible in the course of my writing in English—that’s why there are those moments of untranslated Portuguese in the book (though I still try to provide a gloss so that they can be understood).

“Though I like to think of this book in my own conception as if it was written by Lucia in Portuguese and translated by me… I feel a duty to balance my reading between English and Portuguese; and I feel a duty to engage with Portuguese as much as possible in the course of my writing in English”

3. You are also a stand-up comedian. Do you conceive of your reading audience differently from a comedy audience? How so?

The audiences are totally different. The way I conceive of it is that reading and literature is a very cloistered private experience while stand-up is acutely public. Though, really stand-up and reading are both complex forms of thinking; while you’re reading and while you’re watching a comedy performance, you’re letting someone else do the thinking for you (the difference being if you’re reading it’s probably sober and quiet but while watching stand-up you’re probably a little sauced up noticing how the people around you are reacting also). But also like, stand-up gotta be much more egalitarian and accessible than a novel because if a concept isn’t comprehensible you won’t get any laughs and so you failed; while sometimes in a novel, it’s in the ambiguity and in what you don’t totally understand where you can push for the deeper meaning.

4. There are a lot of phases to publishing a book that not everybody knows about. Was there a point you would say was the most surprising or challenging for you as a debut author?

The whole thing was harder than I thought! Especially the phase of getting it from a finished manuscript to a publishing house. It was cold and lonely and quiet for a while. And humbling because I didn’t realize how finished my manuscript needed to be. I rewrote the whole thing from scratch like nine times. If I had known how many times I would need to do that to get it right… I don’t know man. I’m glad I was naive!

“Stand-up and reading are both complex forms of thinking; while you’re reading and while you’re watching a comedy performance, you’re letting someone else do the thinking for you.”

5. Family fortunes and inevitable inheritances animate Tropicália. If you could claim any writers from the past as part of your own literary genealogy, who would your ancestors be?

There are countless authors I love and am indebted to. If I could choose my American ancestors I would pick William Faulkner and Toni Morrison—the two quintessential American writers, I think. And lusophonically João Guimarães Rosa and Antonio Lobo Antunes (who coincidentally has the exact same birthday as my real grandfather). These four writers have in common a boundless ambition formally and linguistically in masterpiece after masterpiece; and they don’t write about anything easy, it’s only hefty concerns: love, sin, guilt, redemption, identity, and how to live life in the face of death. And yet all these heady themes come through in magnificent stories. Plus, all four are ardently provincial—I think the only way to access universal themes is through the minutely specific.

6. What do you read (or not read) when you’re writing?

Ideally I’m always reading and always writing. I try to hit a diverse array; contemporary, old and musty, bestsellers, dense and difficult (not much nonfiction…). But to get in a real write-y language-y rhythm I’m always going back to my favorite poets: Emily Dickinson, Ana Luisa Amaral, John Berryman, and Haroldo de Campos. My favorite way to work is just to let everything I’m reading at the moment, all the different energies, influence the writing.

7. What role does community play in your writing process? Do you have a writing group, or trusted readers who you rely on for feedback?

I’m pretty coy about showing my work to anybody. My family and my close friends didn’t even know I was writing a novel until it was completely finished, and they didn’t read it until it was in the physical galleys. I did an MFA and though there were some wonderful readers in my workshops, it was often very frustrating and I didn’t like it. I have one friend though who is a writer and I share my work with him when it is very far along. Maybe it’s the wrong way to think about it but related to the stand-up question above, in my mind novel writing is a totally solitary private process while on the other hand stand up is totally collaborative (with the audience) and public.

8. Have you ever had to navigate censorship—or self-censorship—in your writing?

In this book, I wrote several first person perspectives of Selves that are not similar to mine. Daniel is the most similar by far, and I could’ve told the whole story from his perspective, but I think it would’ve been very limited, and the composition of the book would’ve been less joyful for me. Like Lucia for example is a woman who is unsure of her paternity and her father might be black; that is far from my experience. But I was interested in that because like many white Brazilians, I have ancestors who were slaves, but because of the fact that there was no concept of the One Drop Rule in Brazilian society, my family’s history turned out very differently than it would’ve in the United States. This book (like the Tropicália movement) is concerned with what the American gaze does, and so I thought it would be interesting to put the American gaze on race in the case of one specific character. It’s a thorny issue to write outside of your identity; what I’m not trying to do is write about what it means to be Black or what it means to be a woman—I have absolutely no authority on those questions. I was trying to imagine specific lives and I hope I did it with care and respect and truth.

“This book is concerned with what the American gaze does, and so I thought it would be interesting to put the American gaze on race in the case of one specific character.”

9. Writing is often a private and intimate process. This week, Tropicália will also belong to readers. How have you prepared for that?

I know what I said about the coyness I feel sharing a book, but it’s amazing and exciting that it’s going to be out in the world. The book doesn’t belong to me anymore.

10. Finally, it’s a huge milestone publishing your first novel. What’s next for you?

The second novel! And hopefully many more after that.

Harold Rogers was born in Steubenville, Ohio, to an American father and a Brazilian mother and grew up between the United States and Rio de Janeiro. He holds a BA in philosophy from Miami University in Ohio, and an MFA from Columbia University. He lives in New York City, where he works as a boxing coach and a stand-up comedian.