In October 2015, the Myanmar poet Maung Saung Kha posted a poem on Facebook: “I have the president’s portrait tattooed on my penis / How disgusted my wife is.”

The internet’s response was immediate and widespread. While the post quickly accumulated likes and shares, the president’s office warned of retribution. Within hours, police arrived at Saung Kha’s door.

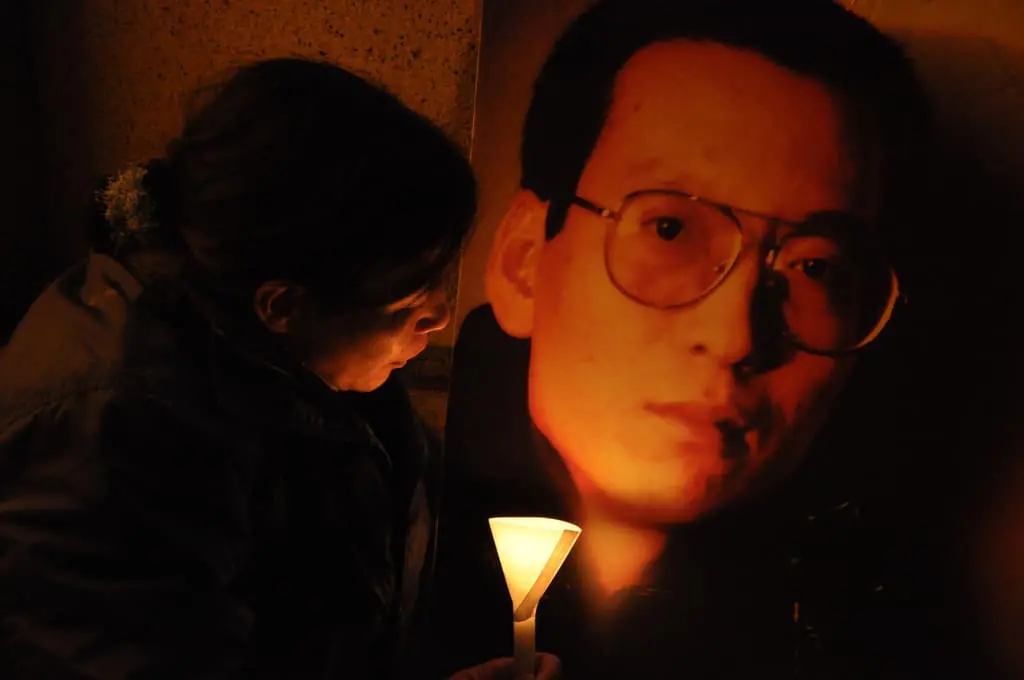

Thousands would come to read of Saung Kha’s hyper-political penis. Articles about him emerged on multiple international media outlets. He was profiled in The New Yorker. Through his imprisonment and subsequent trial, he became an international emblem of free speech.

A month after Saung Kha’s arrest, Myanmar held its first free democratic elections. The National League for Democracy (NLD) won an overwhelmingly large number of seats, and the ascent of Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi ushered in a period of hope. Among the most hopeful were writers and activists. After a decades-long military junta, the rise of the NLD suggested a future of free expression.

In the years since the election, though, it has become clear that Myanmar’s utopian vision is not to be. Violations of free speech have had pervasive consequences throughout the country. In both metropolitan and rural areas, artists and writers are arrested and jailed. Citizens have been turned in for “defamation” by their coworkers, neighbors, and even, in at least one case, mothers. The number of those imprisoned for exercising free expression is in the dozens and rapidly increasing, despite massive online protests and growing outrage.

The arrests largely stem from Article 66(d) of the 2013 Telecommunications Act, the same law that imprisoned Saung Kha over two years ago. Officially, Article 66(d) states that the accused may receive three years in prison for “extorting, coercing, restraining wrongfully, defaming, disturbing, causing undue influence or threatening any person using a telecommunications network.” The language used in this clause is intentionally vague and covers everything from blackmail to revenge porn to defamation. Its use reflects an arbitrary definition of “justice” that threatens to escalate into something even more monstrous.

Now released from prison, Saung Kha has emerged at the forefront of Myanmar’s resistance movement. He is one of the founding members of the Digital Rights Coalition (DRC), an online advocacy group, which this summer launched a widespread social media push against Article 66(d) that has over 47K followers on Facebook. They have sprouted hashtags and other viral content to fight the crackdown on digital freedom through digital means. They have also created a website that tracks each 66(d) case—the name of the accused, charge, and outcome.

The DRC tracking website is still in beta but already rich with information, bringing to light extensive abuses of Article 66(d): A worker is arrested for posting about factory corruption. A man from the opposition party is arrested for a disparaging post about Suu Kyi. A journalist is arrested for criticizing the police. An activist is charged with defamation for livestreaming a play called We Want No War. Multiple people are arrested for “fake news.”

Sprinkled among these cases are more seemingly legitimate uses of the law, including charges of revenge porn and sexual harassment online, that disguise its slow strangulation of free expression.

In August of 2017, the parliament voted on various reforms to Article 66(d), reducing the maximum sentence to two years and tweaking the language so that only the affected party could press charges. The defamation clause, however, remained intact and seems unlikely to change, despite domestic and international pressure.

Article 66(d)—which has remained unfortunately resilient in the face of mass protest—could mark a slippery slope back into authoritarianism in Myanmar. With it, the NLD has set an anti-free expression precedent.

In the meantime, Saung Kha—poet, ex-prisoner, activist—continues to lead the charge against Article 66(d). He told Reuters, “Freedom of expression is still being threatened as long as clause 66(d) exists.”