As the United Nations warns that Myanmar could descend into “full blown conflict,” the risks to writers, demonstrators, journalists, human rights activists, and artists couldn’t be more dire. Well over 700 people have been killed and thousands more arrested since a military junta took power February 1, cracking down on free assembly, free association, free expression, and the freedom to write.

Here, we outline the seven ways Myanmar’s military leaders have threatened free expression, based on public reporting and our own contact network on the ground.

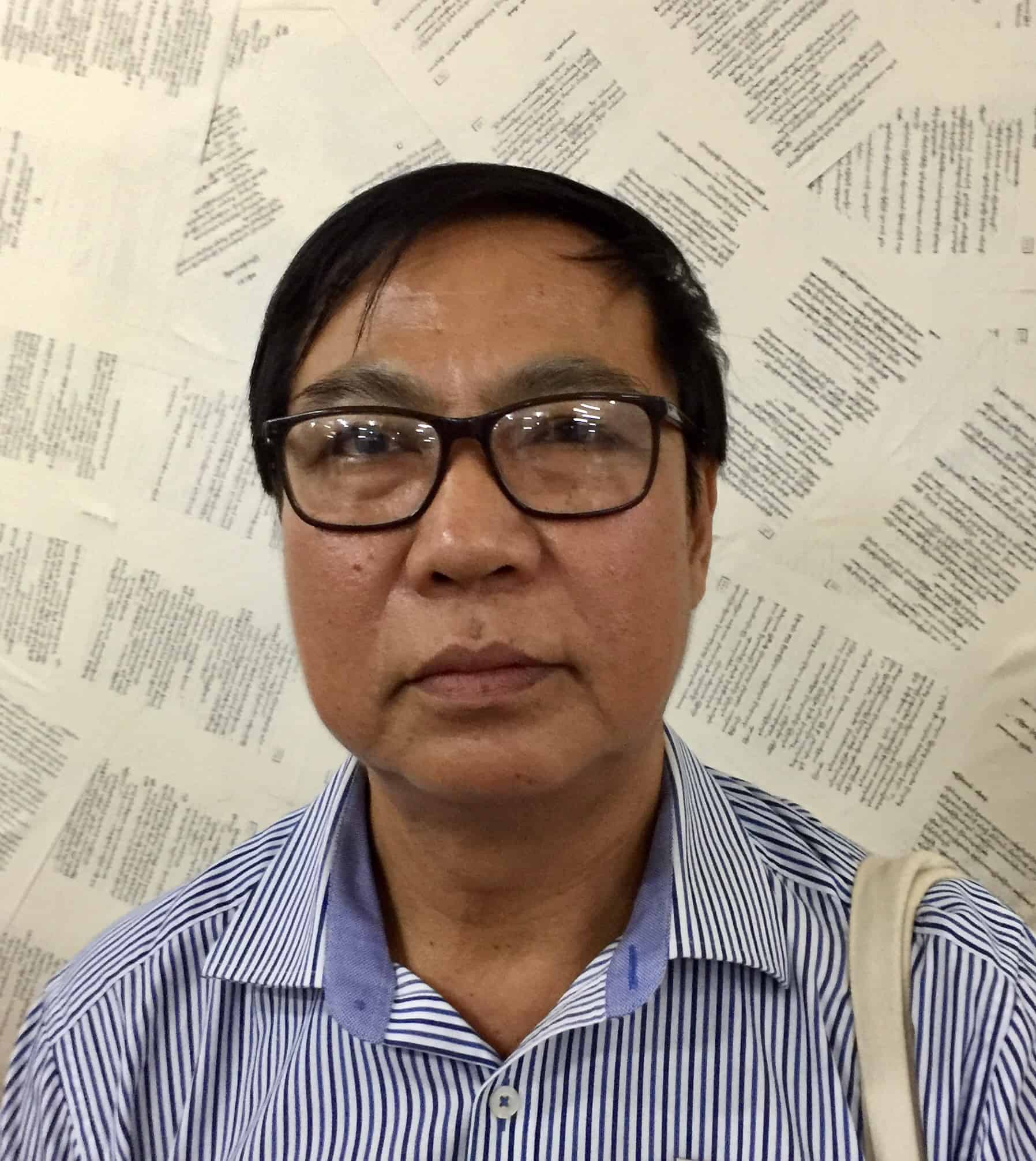

1. Many writers, creative artists, public intellectuals, and cultural figures have been arrested for speaking out against the coup, for participating in protests, or simply without pretext, as part of the broader crackdown.

According to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners-Burma (AAPP), on the day of the coup three writers were immediately arrested—including Than Myint Aung, Maung Thar Cho, and Htin Linn Oo, along with filmmaker Min Htin Ko Ko Gyi. Since then, at least 10 poets and 14 artists have been arrested for their participation in protests. On April 6, more than 100 arrest warrants were issued targeting writers, artists, public influencers, and journalists, including poet and activist Maung Saungkha. Prominent comedian, poet, and activist Zarganar was also recently arrested on unknown charges. Since February, artists have been creating pro-democracy images—many including the three-fingered salute, a Hunger Games-inspired symbol of protest—and sharing them in the streets and across social media.

2. Security forces continue to deploy live ammunition and tear gas against anti-coup protesters.

Myanmar’s security forces have been using lethal force, including choke holds and the use of weapons normally deployed in combat, to target and disperse peaceful and unarmed protesters. At least 726 people have been killed by security forces since the coup began, including a number of journalists and writers. On March 3, poets K Za Win and Daw Kyi Lin Aye (also known as Myint Myint Zin) were killed after military forces fired on them during a demonstration in the city of Monywa.

3. The junta continues to target journalists, media professionals, and citizen journalists, forcing many to go into hiding or leave the country altogether.

Since the coup, at least 56 journalists have been arrested, with at least 38 still held in detention. While some have been released, many are still being detained; following the junta’s imposition of a state of emergency and martial law, they can legally be detained indefinitely. Though some journalists have managed to flee to neighboring Thailand, India, or to ethnic states near Myanmar’s borders, travel opportunities remain restricted due to the pandemic. Still, independent journalists and citizen journalists continue to work covertly, in some cases choosing not to wear press badges or other identifiers so as to blend in with demonstrators.

4. The junta has raided many major English-language and Burmese-language news outlets, forcing them to suspend operations or go underground.

Multiple privately-owned media outlets—including the Standard Times and Myanmar Times newspapers, and the Democratic Voice of Burma, Mizzima, Myanmar Now, 7Day, and Khit Thit media organizations—suspended their operations after the military revoked their licenses to publish and broadcast. While some are continuing to operate underground, they cannot do so openly or legally. This has significantly limited the public’s access to independent news sources in the midst of the crisis.

5. The military’s use of surveillance technology has cast a pall over free expression and made it harder for journalists to do their jobs.

The military is using hacking software, facial recognition technology, and other surveillance tools to identify and charge those who speak out against the coup and against the subsequent crackdown. The use of surveillance has also reportedly led to pressure against journalists from protesters, who fear that live streams or recordings of events on the ground could provide documentation of their participation in protests and put them at increased risk of arrest.

6. Through revisions in criminal codes that already restricted free expression, the junta has now broadened the scope of speech that could be considered a crime.

On February 14, two weeks after the military imposed a state of emergency, Myanmar’s new State Administration Council introduced a number of sweeping legal amendments that stripped important protections for free expression, protest, and privacy rights. Notably, the junta expanded the scope of Section 505 of the Penal Code, a longstanding provision used to target “fake news” and disinformation, to criminalize any comments that “cause fear,” “hinder” or “disturb” military officials or government employees, or cause “hatred, disobedience, [or] disloyalty” toward the military or government. Under this expanded provision, criticizing the military authorities or questioning the legitimacy of the coup could result in up to three years imprisonment. The treason provisions in Section 124 were also broadened, with prison terms up to 20 years possible for ostensible violations. Additional revisions to the Code of Criminal Procedure Amendment Law make offenders under both Sections 124 and 505 able to be arrested without a warrant and ineligible for bail. According to AAPP’s daily-updated database of detentions, many protesters, public figures, and journalists are being charged under Sections 505 of the Penal Code, as well as under the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law or the Natural Disaster Management Law, a provision currently used to enforce COVID-19 restrictions. Since March 15, the military has also declared martial law across Yangon, Myanmar’s biggest city, and multiple other townships throughout the country.

7. The internet has been shut down for 61 consecutive nights.

Starting on February 15, all wireless services were completely disabled, severely hindering the ability of protesters and members of the public to communicate and share information with each other, and of journalists to report news—as of Friday, that’s 61 nights of internet blackouts. Mobile data, public WiFi, and most major social media sites (such as Facebook, which was the country’s primary platform for sharing news and opinion) have been blocked as well. Nevertheless, amid these growing restrictions, activists around the country are distributing printed journals and political pamphlets containing news, poems, and resistance techniques to keep the public engaged and up to date.

Even before the coup, Myanmar ranked among the world’s top ten jailers of writers and public intellectuals, according to PEN America’s 2019 Freedom to Write Index. As daily anti-coup protests continue nationwide, and the COVID-19 crisis intensifies, PEN America supports the people of Myanmar in their fight for free expression and democracy, and continues to call for the immediate release of all those unjustly detained and the restoration of the duly-elected government.

PEN America is actively monitoring the latest news related to free expression in Myanmar on our COVID-19 Free Expression Information Center.