The PEN Ten: An Interview with Daphne Palasi Andreades

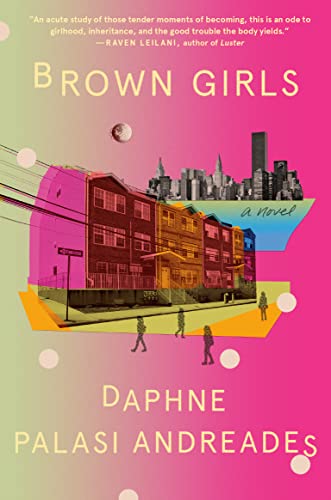

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Daphne Palasi Andreades, author of Brown Girls (Random House, 2022) – Amazon, Bookshop.

Photo by Jingyu Lin

1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you?

I encountered Jhumpa Lahiri’s short story collection, Unaccustomed Earth, and Edwidge Danticat’s novel, The Dew Breaker, for the first time, when I was 18. Reading their work was like stumbling upon a mirror—I had never, up until that point, recognized the immigrant communities I knew so well, reflected in the pages of contemporary literature. I was also mesmerized by the language in their stories. Their sentences were stunning, exquisite. I had also never encountered living, breathing writers who were women of color and immigrant daughters, like me. This had a profound impact because I realized I could pursue writing, too.

2. Why do you think people need stories?

I like that word, “need,” in relation to art and storytelling. “Need” implies a necessity—something essential. Stories have helped me understand myself and the world more deeply. They’ve allowed me to feel less alone, taught me new things, helped me consider other perspectives; they’ve sparked my imagination, transported me to other places and times. The best stories have made me feel grateful to be alive and in awe of how complex life and people are—and in awe that language could capture this. As an artist, I am fascinated by how a form as artificial and contrived as fiction can, in fact, lead to deeper truths.

“I like that word, ‘need,’ in relation to art and storytelling. ‘Need’ implies a necessity—something essential. Stories have helped me understand myself and the world more deeply. They’ve allowed me to feel less alone, taught me new things, helped me consider other perspectives; they’ve sparked my imagination, transported me to other places and times.”

3. What is your favorite bookstore or library?

It’s hard to pick just one! I love wandering around the Strand in Union Square, though. It was the first place I chose to visit once lockdown eased, somewhat. I’m obsessed with the Strand’s towering bookshelves and, of course, all the outdoor carts that sell books for a dollar. In terms of libraries, the Queens Public Library basically raised me. I’d walk 15 minutes along Rockaway Boulevard from my childhood home to the local branch. I’d usually go on the weekends with my little sister in tow. I’d come home with my arms filled with novels, plays, graphic novels, CDs, movies. There’s nothing more wonderful than being a broke kid and having the entire world open up for free.

4. What advice do you have for young writers?

I know it’s not for everyone, but I kept a journal. I people-watched on the subway, at school, at home, and had a compulsion to jot down details and images that I found striking. My journal was the one place where I felt I could be totally honest and free to express myself, and not beholden to social conventions. The practice of keeping a journal helped build my powers of observation, as well as the skill of articulating the abstract and ephemeral. A writer’s job, as I see it, is to take the raw material of life and imagination—both of which are messy, hard to pin down—and transpose it to convey life on the page. It takes practice and discipline to build these skills, not to mention curiosity and drive.

5. What’s something about your writing habits that has changed over time?

I have become a better editor of my own work—that is, more attuned and more ruthless. That’s not to say I don’t still rely on my trusted readers, agent, and editor for their feedback, but I do think, with time and practice, I have become more clear-eyed and critical of my own work—and more honest with myself. I’ve become a better reviser—I’m more comfortable reading with an eye for where I could be more honest on the page, and where the language could be fresh and free of clichés.

“Pursuing a career as an artist was a huge risk. But I see now how much joy and life writing and art have given me—apart from money and financial ‘value.’ I would have encouraged my younger self to remember this fact. I would tell her to keep doing what she was doing: hustling, writing, revising, taking classes, immersing herself in other forms of art, finding communities of like-minded people.”

6. If you had to do something differently as a child or teenager to become a better writer as an adult, what would you do?

It’s a bit complicated to admit this, but I wish I hadn’t worried so much about whether or not pursuing art was the “right” thing to do. I struggled with these anxieties—not just as a teen, but throughout my MFA and after I graduated, too, when COVID swept the world. I say that it’s complicated because my worries weren’t unfounded—they were indeed rooted in reality. How would I make money to afford rent and food? Would I ever publish? What was the point of spending so much time and energy on art, especially if it might not “pay off”?

My worries were also rooted in seeing that no one in my family had pursued a career in the arts, that I am a second-generation immigrant and don’t come from money. Pursuing a career as an artist was a huge risk. But I see now how much joy and life writing and art have given me—apart from money and financial “value.” I would have encouraged my younger self to remember this fact. I would tell her to keep doing what she was doing: hustling, writing, revising, taking classes, immersing herself in other forms of art, finding communities of like-minded people.

7. What is one critique of your work that you have really learned from? On the other hand, what’s the worst piece of advice you’ve ever received on writing?

7. What is one critique of your work that you have really learned from? On the other hand, what’s the worst piece of advice you’ve ever received on writing?

Rather than any specific critique, I have benefitted from when my readers have asked pointed and thoughtful questions about my work. When I was revising Brown Girls, my readers’ questions pushed me to deepen the characters, the conflicts, the world-building, as well as be more specific, clear, and honest.

The worst piece of advice I ever received was being told, from a workshop teacher, “This story is perfect! There are no more edits! Send it out!” This advice was ultimately unhelpful, at least at that point in time—I wasn’t done, and the story needed a LOT of work. I don’t totally blame this professor, but again, I wish I had been a better editor of my own work. But this skill comes, I think, with time.

8. If you could claim any writers from the past as part of your own literary genealogy, who would your ancestors be?

I owe a tribute to all the women, people of color, and immigrant writers and artists who came before me, and subsequently, paved a way for me. From Virginia Woolf, Zora Neale Hurston, Joan Didion, Arundhati Roy, Rita Dove, Natalia Ginzburg, Mieko Kawakami, Mia Alvar, and many, many others—I am indebted to them.

“Queens, NY is an incredibly vibrant, eclectic, and fascinating place—it is the most ethnically and linguistically diverse place in the United States, if not the entire world. It is a borough that’s home to many immigrants—and yet, despite all these things, it’s a place that’s rarely been represented in art and literature. It’s a place on the margins. In Brown Girls, I wanted to change this narrative and place Queens, along with its inhabitants, front and center.”

9. What is your relationship to place and story? Brown Girls takes place in Queens, NY, and its glimmers and less becoming aspects both spill onto the pages of your book. What’s something you really wanted to get across about Queens, especially for readers who might not be intimately acquainted with it?

Queens, NY is an incredibly vibrant, eclectic, and fascinating place—it is the most ethnically and linguistically diverse place in the United States, if not the entire world. It is a borough that’s home to many immigrants—and yet, despite all these things, it’s a place that’s rarely been represented in art and literature. It’s a place on the margins. In Brown Girls, I wanted to change this narrative and place Queens, along with its inhabitants, front and center. I wanted to give readers the privilege of entering into this world and this community.

10. Brown Girls is written in the first-person plural perspective: “Across the classroom, we catch each other’s gazes. Nadira is Pakistani and wears a headscarf, which drapes elegantly beneath her neck. . . . Anjali is Guyanese, and her braid looks like a thick rope that lays heavy against her back. . . . Our teachers snap at Sophie to STOP TALKING NOW, but call her Mae’s name.” The vast majority of novels are, of course, written from first- or third-person singular points of view, focused on one character’s perspective or one omniscient narrative voice. Can you talk about your decision to write from a collective “we” voice?

The year I started writing Brown Girls, I had an incredible fiction workshop professor: the author and cofounder of Tin House, Elissa Schappell. Elissa’s class changed my life and my approach to writing. She encouraged me to take risks in my work: thematic, formal, and also in terms of an emotional vulnerability on the page. This resonated with me deeply. I wanted to do something different than what I’d been reading and studying.

One day, I started writing from this “we” point-of-view. As I drafted the piece, I knew I wanted this “we” to be a chorus of women’s voices: young women of color who were primarily second-generation immigrants, coming of age in Queens, NY. I view the “we” of Brown Girls as deft, fluid, and expansive. It encompasses women across different diasporas in order to highlight the sisterhood and solidarity that exists between them. I also wanted the “we” to illustrate the shared experiences of how colonialism and imperialism had affected the characters’ family histories, to their experiences of racism and marginalization in contemporary America, among other things.

I was very inspired by Julie Otsuka’s gorgeous novel, The Buddha in the Attic, which also uses a choral voice to tell the story.

Daphne Palasi Andreades was born and raised in Queens, NY. She holds an MFA from Columbia University, where she was awarded a Henfield Prize and a Creative Writing Teaching Fellowship. She is the recipient of a Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference scholarship, among other honors. Brown Girls is her first novel.