The PEN Ten: An Interview with the 2021 PEN Prison Writing Award Winners

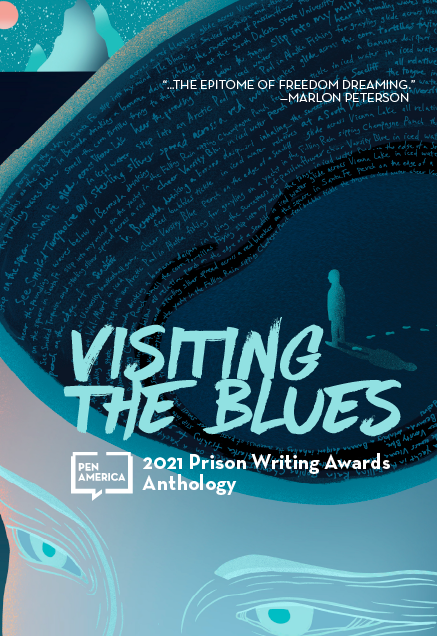

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing intern Peter Watson curates poignant insights from a roster of 2021 PEN Prison Writing Award winners: Timothy James Burke, Jayson Hawkins, Leo Cardez, Jerry Metcalf, Leo Carmona, Zachary Chesser (Zakariyya Ibn Dawud Al-Uqtani), Steven Perez, Kevin Schaeffer, and Alex Tretbar. You can read their award-winning pieces by purchasing a copy of the 2021 Prison Writing Awards anthology, Visiting the Blues.

1. How would you define “writing community?” How does your community guide your work?

1. How would you define “writing community?” How does your community guide your work?

LEO CARDEZ: You wouldn’t believe me if I told you, but I am blessed to be surrounded by talented writers. Yes, here in prison. I mean, how lucky am I to be in this writer’s retreat of sorts—some people pay a lot of money for something not that different from this experience—to witness beautiful art being made and cared for. These are not just my peers, they are my friends. When I first arrived in prison, writing was the thing that made me different. It was my isolation as much as it was my escape from this concrete crypt. I felt like no one understood me, and that was why I wrote and one reason I still do. I have met people who have cared for and validated and encouraged me. It is so much more than community—it is also acceptance and empowerment. They have helped me realize that I do not care if my work “lasts” or “stands the test of time” or makes me rich and famous—that’s boring and vain. My hope is simply that someone may benefit from something I have written, even if just in the smallest of ways. That would be the coolest thing ever.

JERRY METCALF: Though small, my writing community is solid. I know, most people probably feel the same way about their own writing communities, but for us imprisoned men being warehoused here at Thumb Correctional Facility (located in the Great Lock-’Em-Up-and-Throw-Away-the-Key State of Michigan), community is the only writing resource available to us. Here, there are no fancy writing programs. No Google. No Microsoft Word. No childhood friends to help grease the wheels when the going gets tough. Here, if we accomplish anything, we accomplish it on our own, with the aid of a rock-solid core of dedicated men who are always willing to drop what they’re doing and lend a hand.

All this despite the roadblocks and pitfalls tossed in our path by a Department of Corrections hellbent on discouraging prisoner rehabilitation, regardless of cost, logic, or common decency.

“When I first arrived in prison, writing was the thing that made me different. It was my isolation as much as it was my escape from this concrete crypt. I felt like no one understood me, and that was why I wrote and one reason I still do. I have met people who have cared for and validated and encouraged me. It is so much more than community—it is also acceptance and empowerment.”

—Leo Cardez

2. What advice would you give to emerging writers, in the context of prison or otherwise?

LEO CARMONA: The advice I’d give emerging prison writers is to utilize adversity as fuel. Many times, prison isn’t a place where individualism and creativity are nurtured. Sadly, the opposite is usually the case. This can make us frustrated and angry. Where some people may act out, due to a lack of inappropriate coping mechanisms, I like to think that we can convert this anger and resentment into positive energy and creativity. Don’t allow a loud, chaotic, oppressive, and toxic environment to stifle your creativity.

I realize that this is much easier said than done. It actually took me several years to figure out that we can break through the negativity of prison culture. The same way that we use reading as a means of escapism, I have found that writing works the same way for me as well.

CARDEZ: There is no timetable for becoming a good writer. I so often see young writers holding their own work up against the success of their peers, which is the opposite of good art. I remind them I didn’t get my first piece published until five years into delving into the writing life. During those years, I regularly worried about the success attained by other inmate writers compared with mine, and it only served to paralyze me—or worse, to put out work that wasn’t ready or really me. My slice of success only arrived after I chose to stay true to my voice and put in the long hours of reading, writing, and learning. I stopped chasing some imaginary finish line or idea of what a successful writer’s life looked like and focused on trying to reach the readers who needed my words the most.

3. What literature has had a profound impact on you in prison?

ZAKARIYYA IBN DAWUD AL-UQTANI: In prison, I barely have access to two works by the same author, except in genres I have no interest in as a writer. In addition to being terribly new to serious writing, I lack the resources to develop with a traditional concentration of influences. The central problem of my exploration is what could represent Muslim art. I’ve begun to explore how truly Muslim literature might look, and I hope I can contribute, in sha’Allah, to some idea that helps Muslim writers be themselves and stop worrying about Islamophobic expectations.

Resolving this tension cured me of the cynicism toward redemption and reform in my essay “Can I Interest You in a Story?” but writing it was critical to finding myself. I now write with far greater sincerity to who I am as a Muslim, alhamdulillah.

“The advice I’d give emerging prison writers is to utilize adversity as fuel. . . . Where some people may act out, due to a lack of inappropriate coping mechanisms, I like to think that we can convert this anger and resentment into positive energy and creativity. . . . It actually took me several years to figure out that we can break through the negativity of prison culture. The same way that we use reading as a means of escapism, I have found that writing works the same way for me as well.”

—Leo Carmona

TIMOTHY JAMES BURKE: Gary D. Schmidt’s The Wednesday Wars, a Newbery Medal-honored book that I read as an adult in prison. In my book log, I wrote, “Really well done. I laughed and cried in many chapters. Worth sharing. 8+/10.” The title caught my eye, and a quick glance at Schmidt’s prose drew me in. Two years later, I read it again and noted, “Second read better than the first. Magical. Wonderful. Inspirational. 9/10.” I would be remiss, however, if I did not also mention that Jeffrey Eugenides’s 2003 Pulitzer Prize-winning Middlesex is the finest work of literature I’ve encountered.

4. If you could meet the readers of your work, what would you want to say to them?

CARDEZ: I would want to explain to them why I write. That I write in order to survive my own mind, to keep my sanity in my otherworldly existence; to expand my own idea of what I’m capable of, for the boy inside me who still struggles to believe he has value; for the man inside me who trivializes his own suffering; for all the people in custody who feel the same way; to rail against silence and erasure; to find my own narrative; to recover truth; to imagine a future; to record and witness the present, to explain my truth; to redeem myself from the intrinsic pain that comes from trying to unravel my demons and addictions by doing so, to help unpack theirs; because I have questions; because stories inspire me and move me to action; because I enjoy the sound of my own voice; because I am bored; because I am lonely; because it is fun; because it is hard; semicolons and dashes; but mostly I write because of how happy it makes me when it is going well. It is like nothing else.

KEVIN SCHAEFFER: Consider the cost of becoming a prison writer. It’s not my years of wasting away in here. It’s not the emptiness, the dehumanization, the loneliness day in, day out. It’s the crime I committed. The life I took. And the cost is nowhere close to worth it. Not in any universe.

Writing is the only meaningful aspect of my prison life—literally the only one. It’s the only reason I slide myself out of my bunk every morning. The only reason I’m not flailing about from the sheer absurdity of it all and getting myself dragged off screaming to the Hole. But I’d never write another word if it meant undoing any of the pain I’ve caused.

I don’t see my writing as a silver lining, or some lemonade-from-lemons scenario. It’s just a byproduct of the shittiest lose-lose deal in history.

I hope someone can put it to good use.

“My writing process does not look like a process so much as mania. If I am possessed by an intense idea, I’ll scratch its essence on anything that will take ink to anchor it in my mind, then I’ll shake it all out onto paper when I make time and space for the regurgitation. Crafting and smoothing and thesaurusizing come later if necessary.”

—Timothy James Burke

5. What does your writing process look like?

AL-UQTANI: Writing for me is a navigation of truth in and of itself. I use it to explore questions and ideas I can’t resolve by other means. The story of Muslims isn’t often discussed, and I’ve never heard anyone ever bring up how the genocide of millions of Muslims and the destruction of Islamic identity among African slaves impacts Islamophobia today. Writing lets me explore issues like this, and the abstract expressions of poetry and the imaginative freedom of fiction often allow both distance and insight that pure nonfiction cannot achieve. I could get philosophical about the nature of truth, art, and so on, but really my writing is all about ideas, and concepts like “fiction” are merely my tools.

BURKE: My writing process does not look like a process so much as mania. If I am possessed by an intense idea, I’ll scratch its essence on anything that will take ink to anchor it in my mind, then I’ll shake it all out onto paper when I make time and space for the regurgitation. Crafting and smoothing and thesaurusizing come later if necessary.

If I’m working on a longer piece, something with chapters for instance, I’ll write in pencil on lined paper, both sides, for the first draft. The second draft starts with an eraser and pen slicing through the original and rendering it a sloppy, incoherent mess—trails of lines and arrows flying over the pages like international flight plans, though with no legend or compass rose to provide direction for any eyes but my own. The third—and hopefully final, though this never happens—draft is surgical, taking all the severed and damaged bits from the second draft and sewing them back together in places where they better fit. If this is done well, the seams won’t show. If not, the fourth draft involves a mortician’s tools to sussy up the mess and make it look pretty for presentation.

6. What was the last thing that made you laugh? Cry?

BURKE: I’ve been separated from my son for more than 12 years. His mother wants nothing to do with me and has asked her family to cut ties with me as well. A friend of mine still lives in her area and attends her church. On Father’s Day, she saw my son and his mother, and wrote to me about my son, his character, his stature, his recent achievements. When I read that my boy was a passionate, competitive runner, I started sobbing. Couldn’t help it. Snot, spit, the works. At just 15 years old, he was already running the mile 30 seconds faster than my best effort. By the end of the letter, I was laughing and crying, unable to contain the brackish, bittersweet emotions.

“In terms of place, much of my writing revolves around places I have been alone in—and I don’t just mean prison cells. For me, revelation always occurs when I am at a crossroads, and the crossroads (or the realization that I have reached the crossroads) is invariably a window in a place where I am alone. If I weren’t careful, every poem and every story of mine would take place at a little table by a window, in a café or apartment or train, and there would be no other people.”

—Alex Tretbar

STEVEN PEREZ: The last thing that made me cry was when my mother and I had our first video visit. Because of COVID-19, we hadn’t seen each other in almost a year. The two-bedroom cottage my mother and stepfather were renting was so tiny that my daughter had to cross from her room to their room to get to the restroom. I hadn’t seen my daughter in years. She popped out of nowhere, from her bedroom door, in her Schlotzsky’s uniform. A woman since the last time I saw her.

Her brown skin and long black hair. I was behind two masks from my neck to the bottom of my eyes. I said, “Hey beautiful,” and the tears flooded my eyes and I started to discreetly gasp and sob while trying to hold it back. She stopped in her tracks from the surprise of seeing me in their home. She said, “Hey,” and waved her arm in a wax off gesture. “I love you. I gotta go to work.” And she ran off. She didn’t notice the sobbing, but Mom did.

I laughed last night when Kay Dog was pickin’ on Tank. When can anyone, really, pick on a guy named Tank?

7. What does home mean to you? How does a sense of “place” guide your writing?

CARMONA: I spent 19 years daydreaming and plotting my escape from home. I couldn’t wait to get away because it represented a lot of pain, struggle, depressive anguish, and what I thought was oppression. Now, the passage of nearly two decades of time away from it, along with emotional maturation and being imprisoned, has given me a new lens with which to look back at it. It wasn’t all bad. There was some warmth, love, and security, as chaotic and unstable as it was. However, in my youth and inexperience, I allowed the negative aspects of my home life to strongly overshadow the rays of sunshine that can still exist, even in homes where struggle is the central theme.

Sadly for me, “home” no longer exists. None of my relatives that are still alive live in the same homes they did when I left California. Home, for me, is a memory that I am still learning to make peace with. “Growing Pains” is the first thing I’ve written that I can say was actually guided by a “place.” That is, of course, until I finally get around to writing my prison memoir!

“My participation in the [PEN Prison Writing] contest means, to me, that I have an opportunity to be the voice crying out in the wilderness. A chance to be heard. To make a difference. A light in the darkness.”

—Steven Perez

ALEX TRETBAR: Home, by its very nature, is always at some point lost, and the rest of life is spent seeking it and—I hope—regaining it. What complicates things, for me at least, is that “home” is a function of both space and time, and so to a certain extent, it is gone forever. But I also believe that life is a string of homes: I’ve somehow always been able to feel nostalgia for every moment in my past, as if I am perpetually frozen in the act of leaving—leaving home. If I were able to consistently remember this and transpose it into the present, I would be home forever.

In terms of place, much of my writing revolves around places I have been alone in—and I don’t just mean prison cells. For me, revelation always occurs when I am at a crossroads, and the crossroads (or the realization that I have reached the crossroads) is invariably a window in a place where I am alone. If I weren’t careful, every poem and every story of mine would take place at a little table by a window, in a café or apartment or train, and there would be no other people, nothing at all except dust on the sill and whatever was crossing my mind.

8. What does your participation in the contest mean to you?

PEREZ: My participation in the contest means, to me, that I have an opportunity to be the voice crying out in the wilderness. A chance to be heard. To make a difference. A light in the darkness.

TRETBAR: When I was being held in an intake/processing facility between jail and prison, my mother sent me the winning poems of that year’s PEN Prison Writing Contest, and I was floored by one in particular: a short impressionistic poem by Brian Batchelor. I remember few words from the poem (“cypress oar” comes to mind), but the image it conveyed is burned into me, a tactile telling of the crossing of the River Styx (on a literal level, by my estimation) and a hand waved in greeting to oblivion, in recognition of the beginning of nothing: the final word (as I recall, and I may be misremembering) was a simple and devastating “Hello—,” and that em dash said more than any combination of words could.

After reading Batchelor’s poem, I set about gathering my own poems to submit to the contest—my participation in it has been like an ongoing conversation in a lightless room with an untold number of voices.

“Am I a writer imprisoned, or has imprisonment made me a writer? Parallel universes aside, imprisonment—and especially long-term imprisonment—does contain all the essential ingredients of a writer’s life: the initial, traumatic severing from the past; the endless emotional turmoil; the vast swaths of shapeable time; the solitude. . . . In that sense, I’m absolutely indebted to prison for my writer’s identity.”

—Kevin Schaeffer

9. Do you identify as a “prison writer?” What does that label mean to you?

SCHAEFFER: For years, I avoided writing about prison at all. I didn’t want to be a “prison writer,” didn’t want to accept that that might be all I was good for, that all-things-prison might really be the creative limits of my life. The material felt too close, too bleak, too crushingly monotonous. When I wrote, I preferred escaping—with my imagination, and all that. But everything proved so porous—prison always seeped in, no matter how hard I tried to forget it.

When I started confronting my circumstances directly, I was shocked by how liberating and therapeutic it turned out to be, as if I were harnessing all the absurd cruelties and frustrations of this life and squishing them down into a shimmering little nugget. It was alchemical.

But then: Am I a writer imprisoned, or has imprisonment made me a writer? Parallel universes aside, imprisonment—and especially long-term imprisonment—does contain all the essential ingredients of a writer’s life: the initial, traumatic severing from the past; the endless emotional turmoil; the vast swaths of shapeable time; the solitude. Add to that the invigorating indifference and pointlessness of the system itself, an incomprehensible force—pure grist—that’s always inspiring reaction. In that sense, I’m absolutely indebted to prison for my writer’s identity. Not that the powers that be should be proud of that. They turn the creative act into something almost spiteful, defiant—a conscious transcendence of the paper citizens they’re so content with clipping out. Hemingway said something like, “Writers are forged in injustice as a sword is forged.” Credit where credit’s due, they never let the forge burn cold.

JAYSON HAWKINS: The tag of “prison writer” can be a double-edged sword. Does it simply mean that I’m writing while incarcerated? Or that somehow my only avenue as a writer must flow through my experiences within prison? Most of my associates despise writing about this place. Having spent the majority of our lives behind bars, the last thing we want to do is dwell on that situation with pen and paper. Stereotypical “prison writing” tends to be of the “wha, wha, poor me” variety, and while there seems to be an audience for that in the free world, serious writers in here hate that shit with a passion. Once you accept responsibility for the role each of us plays in determining our own fate, you quickly lose tolerance for the mutterings of those who have not.

Having said all that, it’s also true that your chances to succeed as a writer inside prison are severely limited. For one, internet access (or even access to a computer) is verboten in here, and most publishers no longer accept snail mail submissions. So when an opportunity for “prison writers”—like the PEN contest—comes along, you’d be a damned fool not to take advantage of it.

“Something like 97 percent of all prisoners get out eventually. There seems to be a general agreement that we would all like to see these men and women leave incarceration in a better mental state than when they went in, but year upon year of dehumanization is a poor formula for improvement. To strive for the justice we claim to want will require finding a balance between punishment and rehabilitation.”

—Jayson Hawkins

10. What does justice mean to you?

METCALF: Justice to me is the pursuit of truth. Nowadays, prosecutors are no longer seeking the truth. They seek victory. They seek notches on the worn leather belt that is their career. They pull out all the stops to garner a conviction, regardless of guilt or innocence. I cannot count the times I’ve read where prosecutors wrote in their legal briefs how “the U.S. Constitution does not guarantee the right to a just trial, it only guarantees the right to a fair trial.” Such bullshit!

As if the Founding Fathers meant for there to be a difference between just and fair. And to think, we call America the land of the free? With five percent of the world’s population and 28 percent of the world’s prison population, we’re anything but free. We should be ashamed of ourselves.

HAWKINS: We do not live in a “just” society. If we did, myself and many of my friends and associates would have been put to death long ago—at least from a purely retributive standpoint. Yet, it is also hard to rationalize how warehousing individuals for decades on end serves the greater good of society. Something like 97 percent of all prisoners get out eventually. There seems to be a general agreement that we would all like to see these men and women leave incarceration in a better mental state than when they went in, but year upon year of dehumanization is a poor formula for improvement. To strive for the justice we claim to want will require finding a balance between punishment and rehabilitation.