The PEN Ten: An Interview with Lisa Hiton

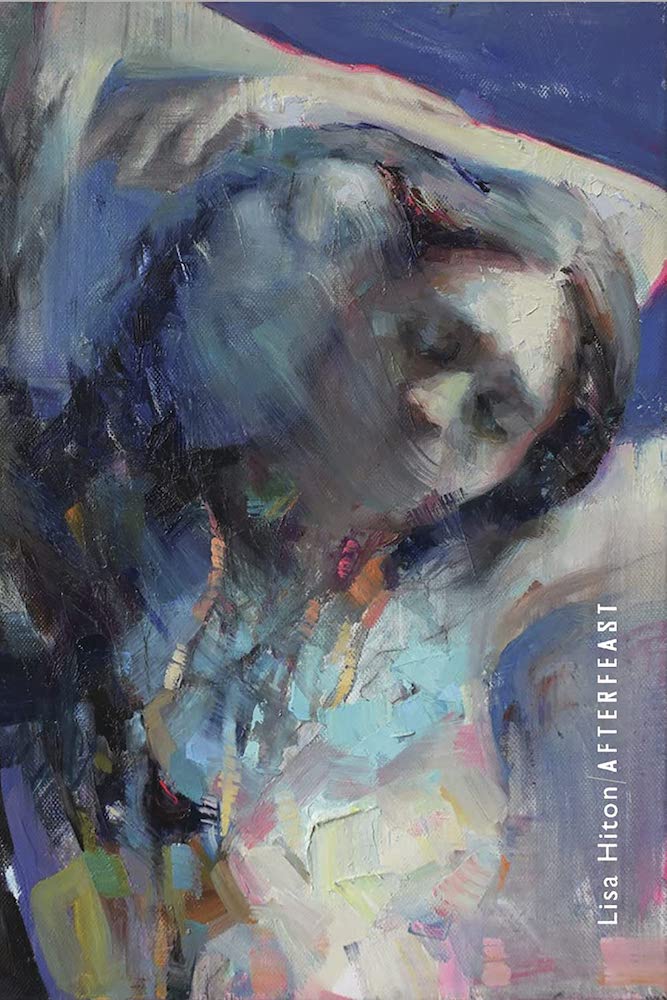

The PEN Ten is PEN America’s weekly interview series. This week, Viviane Eng speaks with Lisa Hiton, author of Afterfeast (Tupelo Press, 2021) – Amazon, Bookshop.

1. What is the most daring thing you’ve put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

1. What is the most daring thing you’ve put into words? Have you ever written something you wish you could take back?

I’m not sure I’d be so bold to say that much I’ve written has been daring to anyone other than perhaps myself. If I’m daring in writing, it’s because the writer has control of the whole encounter, whereas saying something daring in real time requires more bravery. Coming out comes to mind. Regardless of how kind many people in my life have been in response, saying I’m gay over and over continues to be harder than writing it.

In this book, I think “The Senator”—a poem about sexual violence and the politics around it—dares to terrify the reader more than the other poems. I wonder how “Variation on Testimony” will be received over time as it takes up a homicidal and homophobic persona. I think “Bakery,” which “plays the Anne Frank game,” is another poem that dares the reader to take on all kinds of complicated visions and points of view. I even think the poems that address love between women dare the reader to take up the “I” in a way that might challenge their own understanding of desire or even sexuality. For example, the final epigram of the opening poem, “Pastoral,” reads “I thought I wanted a sister. / What I wanted was a lover.” The reader has to occupy the position of that speaker, and doing so might illuminate or challenge something in said reader, even if it’s only a momentary exercise.

2. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired?

Most of the time, I write at night. I find that I need to feel that time doesn’t exist—which the sun moving is a reminder of—in order to enter the depths of consciousness required for writing. I also consider myself to have grown up in a black box theater, so I feel comfortable with no windows and no sense of time. This is true of my time in film school also, where you’re placed in the basement—when you need a set, the light can be entirely manipulated and unchanging; when you edit, you have no idea how many days or meals have passed.

“If I’m daring in writing, it’s because the writer has control of the whole encounter, whereas saying something daring in real time requires more bravery. Coming out comes to mind. Regardless of how kind many people in my life have been in response, saying I’m gay over and over continues to be harder than writing it.”

3. What’s a piece of art (literary or not) that moves you and mobilizes your work?

For this book especially, the work of Quentin Tarantino is predominant to me—in particular, Inglourious Basterds. It is one of Tarantino’s three perfect films. The opening of the film brings us into the home of a French dairy farmer who is hiding a Jewish family below the floorboards. We wait nearly 20 minutes with this knowledge as Colonel Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz) enters the house to ask many questions with the polite rigidity of a horrifying Nazi—one who believes his dogma of following rules will save him from future retribution or judgement. We wait for violence. We wait and wait. And no amount of violence—the true violence of the Holocaust, or the imagined version of violence Tarantino grants the Basterds—would change the historic outcome of this particular genocide. It is the quintessential lesson of this film.

Lyric poems, like film, are time-bound. Where one has a first frame and a last, the other has an opening line and a final line. One cuts to black. One cuts to white. To be a master of time: That is what film and Modernism have taught me. Consciousness and imagination are infinite, but our time is not. The tension between those two modes fuels me and pulls my artistic compass in wild directions, no matter the project.

4. What’s something about your writing habits that has changed over time?

I often tell my students that writing habits are for prose writers. When I read all of those Paris Review interviews where a novelist like Toni Morrison describes “writing into the light” every single morning, I become anxious at the thought! One of my longtime mentors, Carolyn Forché, encourages writing habits—ways of writing every day even if you don’t want to or don’t feel you have anything to say. I think for some poets, that is a good way to mitigate the anxiety of not writing. Outside of school or workshop environments, I find writing can be nearly impossible. I tend to be a bit more like one of my other mentors, Louise Glück, who can go for so long without writing much and then an entire book comes at once.

Now that I’ve been away from school long enough, I trust that the writing will come—it often overcomes when it finally arrives. I trust that when my world is challenged or when I travel, I will experience that sense of vertigo necessary to receive the lightning when it strikes.

“Lyric poems, like film, are time-bound. Where one has a first frame and a last, the other has an opening line and a final line. One cuts to black. One cuts to white. To be a master of time: That is what film and Modernism have taught me. Consciousness and imagination are infinite, but our time is not.”

5. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss?

Virginia Woolf. I don’t know what I’d ask her or want her to say, but to have known her at all might give some insight to a mind that can arrive at such clarity and gravitas.

6. What was one of the most surprising things you learned in writing your book?

That, as it turns out, I’m gay. I think the title also showed me that this book is about being belated in so many ways—to the body, to gender, to sexuality, to history. I didn’t intend to write that book, but it is the book that arrived, in the end.

7. In Afterfeast, your poems delve into the immutability and immortality of history. While visiting European cities with a companion, the narrator encounters ruins of a synagogue, which emphasizes the simultaneous proximity and dislocation felt toward her family’s Jewish roots, ones that are so tied up in migration and persecution. There is an inevitable, ineffable tension between the narrator and the companion, who has German, non-Jewish ancestry. The two are so far away from the past, yet literally steeped in it—borne of it: “If I am close to you, I am close to the war,” the narrator thinks. In places like Greece, where a number of your poems take place, it’s probably fairly easy to go about daily life while taking note of vestiges from the past. But of course, history is everywhere, even when there aren’t ruins around. Do you find yourself contemplating the conflation of past and present when you’re in the states? If so, what novel perspectives does doing so help you see?

7. In Afterfeast, your poems delve into the immutability and immortality of history. While visiting European cities with a companion, the narrator encounters ruins of a synagogue, which emphasizes the simultaneous proximity and dislocation felt toward her family’s Jewish roots, ones that are so tied up in migration and persecution. There is an inevitable, ineffable tension between the narrator and the companion, who has German, non-Jewish ancestry. The two are so far away from the past, yet literally steeped in it—borne of it: “If I am close to you, I am close to the war,” the narrator thinks. In places like Greece, where a number of your poems take place, it’s probably fairly easy to go about daily life while taking note of vestiges from the past. But of course, history is everywhere, even when there aren’t ruins around. Do you find yourself contemplating the conflation of past and present when you’re in the states? If so, what novel perspectives does doing so help you see?

The poem you specifically mention is “Dislocated Cities.” My friend who is also a poet, Richie Hofmann, took me to Speyer. Speyer is a medieval town outside of Frankfurt. His family used to run a bakery there. We had inverted anxieties while walking around this town—inverted in our gender, our sexuality, and our ethnographies. During the 1200s, Jews were brought to Speyer to stimulate the economy. So Richie’s direct history is preserved in this location, yes. Both the migration and plight of the Jew are evidenced there too.

So much of the book was written in Greece, specifically in Thessaloniki, which was the last port of entry through the States for my mother’s family. I couldn’t quite understand my Sephardic heritage or my American Jewish heritage without the idea that most of the time, you have to enter Europe through Germany to get to Greece. And so, the poem is about how the cities—and the people in them—are dislocated. I think it’s also about how the body may carry certain griefs across borders and languages.

“So much of the book was written in Greece, specifically in Thessaloniki, which was the last port of entry through the States for my mother’s family. I couldn’t quite understand my Sephardic heritage or my American Jewish heritage without the idea that most of the time, you have to enter Europe through Germany to get to Greece. And so, the poem [“Dislocated Cities”] is about how the cities—and the people in them—are dislocated. I think it’s also about how the body may carry certain griefs across borders and languages.”

The past and present conflate in the States, too. The double diaspora of the Sephardic Jew is clear to me in the States. There’s been an effort at a Yiddish revival, but Ladino is considered dead outside of some of the music we have. In Chicago, I think about the conflation of the past and present when I’m in West Rogers Park. When my elders came to the States, it was the Great Vest Side (Yiddish speaking Jews pronounce the W as V) because there were so many Yiddish-speaking immigrants there. There are new stories on those blocks now.

It’s also impossible in America not to see all kinds of conflation of the past and present around you. When I lived in Boston for 11 years, I saw my favorite blocks in the South End change from a more underground haven for queer people to some of the most coveted real estate for young white families and fine dining restaurants. There is evidence of migration and displacement everywhere.

I think buried in your question is one about whiteness, too. And as much as my personal intersections are at the top of mind most of the time, it’s impossible not to see the violence of the past all over the States. Even in my small hometown of Deerfield, IL, we’ve only recently begun to reckon with part of our racist past. There was a fight to integrate Deerfield in 1959. The crisis between those in the town trying to halt the housing development and those who supported the civil rights effort gathered the attention of figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Eleanor Roosevelt. James Baldwin even came to our town to try to help.

I grew up not knowing anything about this. I walked across the street to the park and pool not knowing it was supposed to be housing all along, not knowing it was named for a man whose racist efforts erected a park made instead of homes. Sixty years later, the park has been renamed and the public library has an entire archive of materials about this history. There are even programs and events for our schools and village members to learn about this time in our history and begin to reckon with it.

8. What is a moment of frustration that you’ve encountered in the writing process, and how did you overcome it?

I think it’s hard to write while you’re also publishing a book. This book is so old to me—I believe the most recent poem in it was written in 2014. And so when it was time to begin the process of proofing, I had days where I couldn’t stand some of the poems or lines. Forché once said something in a workshop about how you must revise your work while the clay is still wet. And with another book and a half’s worth of poems written since 2014, my obsessions and desires are different. My sense of hope is different. What I’m willing to face is different. It was hard to go back into the pain and wonder I felt while writing the poems in Afterfeast after so long. I had to learn to love the poems as they are in some cases—the clay was already dry. I just have to hope the best work is still ahead of me.

“So often, I read work that is beautifully forgettable. As an example: Pristine couplets have their place, but amid thousands of poems, they tire. Is the couplet arbitrary or solely aesthetic? Or are there stakes in what’s been coupled or uncoupled in the world of a given poem? I think in a world where my generation wavers between grief and irreverence, we’ve seen mostly great works that thrive on irreverence and flippancy. Unless the irreverence unveils its purpose as a protector from pain or danger, I’m not hoping to invest in it or suggest that other readers should.”

9. Outside of your own writing, you are the poetry editor of The Adroit Journal. What are some things you’re paying particular attention to right now, when looking for writers and poetry to amplify? What types of stories do you wish were being published more in today’s literary landscape?

As an editor at The Adroit Journal (and as a producer of “Queer Poem-a-Day”), I’m looking for work that has stakes. So often, I read work that is beautifully forgettable. As an example: Pristine couplets have their place, but amid thousands of poems, they tire. Is the couplet arbitrary or solely aesthetic? Or are there stakes in what’s been coupled or uncoupled in the world of a given poem? I think in a world where my generation wavers between grief and irreverence, we’ve seen mostly great works that thrive on irreverence and flippancy. Unless the irreverence unveils its purpose as a protector from pain or danger, I’m not hoping to invest in it or suggest that other readers should.

Luckily, there are many editors at The Adroit Journal, so we have excellent arguments about what speaks to our cultural moment, what offsets our own body-politics, and what work stands to challenge ourselves and our readers about poetics and how they may stand to help us shift larger cultural paradigms. I think often of Adrienne Rich’s snarky and serious work, “As if your life depends on it…” I take her at her word.

10. What advice would you give to a writer who is trying to publish their book—not just in general, but especially in this current climate?

I’m a terrible person to advise others on book publication. While my peer group is on their way to second or third books, impressive fellowships, professorships, and so on, it took me a decade to go from my MFA thesis to a book in the world with mostly failure and rejection to accompany the journey. Further, a first book in poetry is nearly impossible—you have no advocates (like agents, publicists, editors, etc.) and most first books are prizes, which means that even if a publisher likes your book, the judge of the prize that year may not. You have to be obsessed enough with writing to keep writing.

The best thing you can do is find a group of other writers who you can share your work with, and more importantly, who keep you writing. I am so grateful to the few writers in my life who read my work and who let me read theirs. The writing has to be the life source.

Lisa Hiton is the author of Afterfeast (Tupelo Press 2021), which won the Dorset Prize. She holds degrees from Boston University and Harvard University. Her work has appeared in Lambda Literary, The Common, and Kenyon Review, and has been honored with AWP’s Kurt Brown Prize. She is the poetry editor of The Adroit Journal. She is also the founder and co-producer of “Queer Poem-a-Day” at the Deerfield Public Library.